Writing the Personal Barbara Bridger 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ijoaquin Interior.Indd

irst paragraph of teaser text goes here. F Second paragraph of teaser text goes here. Third paragraph of teaser text goes here. And so on. Dimension W is an imprint of Crossroad Press Publishing Copyright © 2015 by Melvin Litton Cover by Dave Dodd Design by Aaron Rosenberg ISBN 978-0-9834xxx-x All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Crossroad Press at 141 Brayden Dr., Hertford, NC 27944 www.crossroadpress.com First edition I, Joaquin MELVIN LITTON This sketch of Joaquín Murrieta, featured in The Overland, November 1895, was supposedly drawn directly from his head preserved in alcohol. (Courtesy of the California State Library Rare Periodical Collection.) Of Joaquin From Reminiscences of a Ranger by Major Horace Bell (1830—1918) o one will deny the assertion that Joaquin in his organizations, “Nand the successful ramifications of his various bands, his eluding capture, the secret intelligence conveyed from points remote from each other, manifested a degree of executive ability and genius that well fitted him for a more honorable position than that of chief of a band of robbers. In any country in America except the United States, the bold defiance of the power of the government, a half year’s suc- cessful resistance, a continuous conflict with the military and civil authorities and the armed populace—the writer repeats that in any other country in America other than the United States—the opera- tions of Joaquin Murrieta would have been dignified by the title of revolution, and the leader with that of rebel chief. -

Troubled Times 2Nd Edition Ebook Free Download

TROUBLED TIMES 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David W Frayer | 9781134385300 | | | | | Troubled Times 2nd edition PDF Book Second, arcane magic a force channeled from The Weave by wizards and sorcerers ceased to be regulated by its steward, Mystra , and became dangerously unpredictable. Look for signs of the changing seasons, or ways you see your children growing. Children will also appreciate opportunities to help others, so include them when you can. If faith is a part of your life, stay connected to your faith community. Be as consistent and calm as you can. Cormyr: A Novel Paperback. Just carve out some time for yourself to do something you find relaxing or refreshing. Evans , Paul S. The following are deities who were killed or incapacitated during the Time of Troubles:. Maybe you felt that your family was thriving before the coronavirus pandemic. Learn about what to expect in each stage of development. Universal Conquest Wiki. Categories :. Retrieved 10 May City of Splendors: Waterdeep. On Hallowed Ground. Nearly a decade after Cast split up shortly after the release of their fourth album Beetroot , lead singer and songwriter John Power had already released three solo albums when he started writing material that he felt was more suited to the band. Toddlers, for example, thrive with regular mealtimes, playtime, nap time, bath time, and bedtime. Having caring people in our life helps us feel secure, confident, and empowered. Kicking Up the Dust Troubled Times 2nd edition Writer However, unlike when a god usually sends an avatar and its true form resides usually on one of the Outer Planes, the gods were all demoted and this was the only form they had at the time, making them very vulnerable. -

RITUAL UNION Reviewed Plus: All Your Oxford Music News, Reviews and Previews, Plus Seven Pages of Local Gigs for November

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 280 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “We“We areare thethe definitiondefinition ofof BritishBritish reservereserve whenwhen itit comescomes toto anger.anger. WeWe probablyprobably dodo releaserelease aa fairfair bitbit photo: Helen Messenger throughthrough ourour music.”music.” SELFCultural exchanges, terrible tattoos HELP and dancing round the kitchen with Oxford’s pop punk stars. Also in this issue: Introducing WORRY SAVE THE CELLAR - fundraising campaign launched RITUAL UNION reviewed plus: All your Oxford music news, reviews and previews, plus seven pages of local gigs for November. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk SUPERNORMAL FESTIVAL returns in 2019. The three-day celebration of leftfield and underground music and art takes place at Braziers Park in Ipsden RADIOHEAD’S PHIL SELWAY, RIDE’S MARK GARDENER over the weekend of the 2nd-4th and Gaz Coombes are among the musicians who have recorded August. The festival took a year messages of support for the Save The Cellar fundraising campaign, th off this year, organisers citing the which is officially launched on the 25 October. workload involved for what is a The local stars are among a host of artists rallying behind the photo by Helen Messenger group of volunteers. campaign as the venue fights for its survival in the wake of having its Regularly quoted as the best fire capacity slashed after its stairway was deemed 30cm too narrow. -

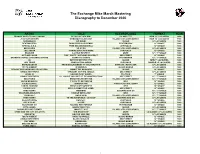

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Use of Theses

Australian National University THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. THE 2/2 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION: THE HISTORY OF A GHXJP EXPHUHCE MARGARET ANN BARTER NOVEMBER 1989 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University CERTIFICATE Except vrtiere acknowledged in the text this thesis represents my own work. The thesis has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I am indebted to the men of 2/2 Battalion: those I got to know, and those long-dead whan I met in letters and diaries. In 1981-1982 I received invaluable help from Michael Piggott, Bill Fogarty and Geoff McKeown at the Australian War Memorial's Research Library. At that time I also met and talked with many scholars about war, soldiers and history. For their special interest and encouragement I thank the late Professors Sir Keith Hancock and John Robertson. For their helpful advice I thank EXidley McCarthy and Drs David Horner, Robert O'Neill and Hank Nelson. Many more people than I can name here helped me in various ways but two deserve mention; Virginia Stuart-Smith for her very timely support and Olwyn Green, a fellow traveller down 2/2 paths since 1981, for her sustaining interest. -

Where the Dead Remain

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2010 Where the Dead Remain Bryan Camp University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Camp, Bryan, "Where the Dead Remain" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1250. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1250 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Where the Dead Remain A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre, and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Bryan Camp B.A. Southeastern Louisiana University, 2006 December 2010 Copyright 2010, Bryan Camp ii for New Orleans, my city, and for Elizabeth, my home iii A man's house burns down. The smoking wreckage represents only a ruined home that was dear through years of use and pleasant associations. -

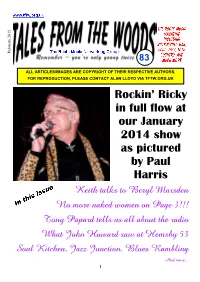

Rockin' Ricky in Full Flow at Our January 2014 Show As Pictured By

February 2015 February 83 ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Rockin’ Ricky in full flow at our January 2014 show as pictured by Paul Harris Keith talks to Beryl Marsden No more naked women on Page 3!!! Tony Papard tells us all about the radio What John Howard saw at Hemsby 53 Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more... 1 by Paul Harris THE BUILD UP It must have been in 2004 that I was working on my computer and listening on the internet to Radio KBON based in Eunice, Louisiana. This station concentrates on playing local Louisiana music which includes my favoured genres of New Orleans R&B, Swamp Pop, Cajun and Zydeco. Station owner Paul Marx was the DJ and suddenly I was aurally aware of a Fats Domino record that I did not recognise. Being a Domino fanatic I thought I knew all his material so was rather surprised. After listening intently I came to the conclusion that in fact it was not Fats but it was the closest I had ever heard in voice, piano, style of material, backing, etc. Luckily this friendly station offers the facility to email the DJ © Paul Harris whilst on air so I immediately dispatched an enquiry seeking full details of the artist and the recording. Amazingly I received a response within fifteen minutes or so. The artist was Al ‘Lil Fats’ Jackson, the CD was entitled ‘Poor Man’s Blues’, recorded in 1997 and released on Kolab records KL-9101. -

British Volunteers Were at the Station, Waiting to Board the Next Train Back to the Coast

1 My Heart Forgets To Beat “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.” - Oscar Wilde, “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” 2 Part One: April,1937 Valentian girl with boots and balls His kisses will say, “I want you, Laura” and today more than their tongues will speak. Afterwards hand-in-hand they will enter the RED STAR café and the comrades may feast their eyes. Meanwhile, Vaughan holds two cans of caviar under her nose, courtesy of Uncle Joe, Just an itsy-bitsy picnic! Look, a bunch of the sweet onions; and here, fresh bread from the company stores. Already packed is a flask of red wine drawn from the oak of La Mancha, and a tin of Ukrainian cigarettes. She gives a cry, Ah, the ones you bend in case the tobacco falls out. If that is not enough, into the knapsack he carries everywhere like a donkey go water & biscuits, billycan, notebook, fountain pen and the heavy old revolver he bought off a smuggler in Barcelona. He glances up and smiles, It's not too far into the countryside. Not too far? On foot, you should note, across fields crawling with enemies. He averts his eyes, Our own little reconnaissance sortie, my little brown dove. What a schemer! They will leave town, find trees for shade and grass for their behinds. He will 3 ply her with food, drink and when her patience is at an end, prove his manhood. Everyone knows what caviar is good for. Laura, he chides in abysmal Spanish learnt from the poems of Lorca, Drunken gendarmes are beating on the doors. -

Digger Guestbook Redux (1995 to 2004)

Digger Archives Online Guestbook – entries, anecdotes, and associated material From: Billy Batman ([email protected]), 12/08/95. Subterranean whispers of maddening visions . The Digger Papers (August 1968) The Birth of Digger Batman by Kirby Doyle O sky glorious, O sky divine People dominions nations Heavens door O walking deliverance O Passage People O People Machines Animals Trees Towers & Bridges O Seed O colors Faces All Moving Things Life, hello . I want to tell you of the birth of Digger. Morning, about 9:30, July 5th, 1967 — clear and sunny upon the city, the sky echoing with happiness, the streets still and clean and just to walk on them is to be silent in the bright rising from the night after a big 4th of July electric music and free feed celebration out in the park where Emmett and the cooks from the Fillmore had made barbecue for about 4,000 people. I am up early and out into the street from Peter Cohon’s on Pine Street where the Communication Company lived — out and standing in the good day with the smiles all over me, just letting the warmth and the light honey about on me, my clothes glowing and the fine feeling seeping to the skin and a touch tasting to my innards, and O the head is just wanting to face with smiles in all directions. I had driven Susan Parker to the airport a couple days before and still had her car so I swings over a few blocks to Geary thinking to have coffee and a morning smoke with the Jahrmarkts, Billy and Joan and the kids. -

Band-O-Rama with the Organ, the Rogers Kd Lang Sisters, Devics & the Chalets Elin Ruth Bic Runga Neko Case Terri Walker Emm Gryner Marissa Nadler Welcome To

SPRING 2006 a women in music compendium wears the trousers the pipettes star in our massive plus... band-o-rama with the organ, the rogers kd lang sisters, devics & the chalets elin ruth bic runga neko case terri walker emm gryner marissa nadler welcome to... wears the trousers Hello again! wears the trousers Since you’ve been gone dear friends www.thetrousers.co.uk we’ve been ever so busy. Things got off to www.myspace.com/wearsthetrousers an auspicious start in January when we 17B Church Crescent were invited to take part in a new national Muswell Hill London N10 3NA digital preservation scheme in conjunction +44 (0)20 8444 1853 with The British Library and The Women’s [email protected] Library. Wears The Trousers was chosen as one of the first 150 Editor Alan Pedder sites selected to form the basis of a Women’s Issues collection. Of course we were only too happy to accept and you may have Deputy Editor Trevor Raggatt noticed the new logos on the website. Basically, what it means is that even if some horrible fate should befall the site as we know Associate Editors Clare Byrne, Stephen Collings, it, Wears The Trousers will still always be available until the end & Rod Thomas of Father Time himself, or something like that anyway. Wears The Trousers is a completely Fear not, however, our heads didn’t swell enough to stop us free, not-for-profit, blood, sweat and from bringing you what is undoubtedly our best issue yet. You tears included resource for all that is new, essential and downright exciting about the want indie icons? We give you Neko Case.