Ijoaquin Interior.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S

GOLDEN TICKET BONUS ISSUE TM www.GoldenTicketAwards.com Vol. 15 • Issue 6.2 SEPTEMBER 2011 Holiday World hosts Golden Ticket event for third time Amusement Today sees the biggest voter response in survey history 2011 . P . I GOLDEN TICKET . V AWARDS BEST OF THE BEST! Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari Host Park • 2011 Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S. MADONNA HORCHER STORY: Tim Baldwin strate the big influx of additional voters. [email protected] Tabulating hundreds of ballots can seem SANTA CLAUS, Indiana — It was Holiday like a somewhat tedious and daunting task, World’s idea for Amusement Today to pres- but a few categories were such close races, ent the Golden Ticket Awards live in 2000. that a handful of winners were not determined The ceremony was on the simple side, and until the very last ballots in the last hour of now over a decade later, the park welcomes tabulation. These ‘nail biters’ always keep us AT for the third time. A lot has changed since on our toes that there is never a guarantee of that time, as the Golden Ticket Awards cere- any category. mony has grown into a popular industry event, The dedication of our voters is also admi- filled with networking opportunities and occa- rable. People have often gone to great lengths sions to see what is considered the best in the to make sure we receive their ballot in time. industry. And as mentioned before, every vote abso- What has also grown is the voter response. lutely counts as just a few ballots determined The 2011 awards saw the biggest response some winning categories. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T12:57:58Z TITLE: 'Muchos Méxicos': Widening the Lens in Rulfo's Cinematic Texts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title 'Muchos Méxicos': widening the lens in Rulfo's cinematic texts Author(s) Brennan, Dylan Joseph Publication date 2015 Original citation Brennan, D. J. 2015. 'Muchos Méxicos': widening the lens in Rulfo's cinematic texts. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2014, Dylan J. Brennan. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1960 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T12:57:58Z TITLE: 'Muchos Méxicos': Widening the Lens in Rulfo's Cinematic Texts. AUTHOR: Dylan Joseph Brennan, M.A. QUALIFICATION SOUGHT: PhD INSTITUTION: National University of Ireland, Cork. (University College Cork) DEPARTMENT: Centre for Mexican Studies, Department of Hispanic Studies. MONTH AND YEAR OF SUBMISSION: Originally submitted July, 2014— resubmitted after Minor Changes in February 2015 HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Prof. Nuala Finnegan, Director of Centre for Mexican Studies. SUPERVISOR: Prof. Nuala Finnegan, Director of Centre for Mexican Studies. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Widening the Focus in Rulfo's Cinematic Texts – An Introduction P.1 1.1 Texts for Cinema? – Rationale and Paramaters P.1 1.2 Methodology P.7 1.3 Muchos Méxicos P.10 1.4 Widening (not shifting) the Focus P.15 1.5 Objectives P.18 2. Inframundos and Fractured Visions – El despojo and La fórmula secreta P.22 2.1 Conception and Synopsis: An Introduction to El despojo -

"ESF Load Sequencer Software Verification & Validation Rept."

' ESF LOAD SEQUENCER SOFTWARE VERIFICATION AND VALIDATION REPORT prepared by: SIMPACT ASSOCIATES'NC. 5520 Ruffin Road San Diego, CA 92123 September 9, 1982 ESF LOAD SEQUENCER SOFTWARE VERIFICATION AND VALIDATION REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Pacae ~ 1 OB JECTIVE ~ o ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ o ~ ~ ~ 1 2. STUDY PROCEDURE AND RESULTS SUMMARY ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ t 0 4 I ~ 0 ~ 2 3. SPECIFICATION REQUIREMENTS ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ ~ ~ 0 t I ~ 4 4 SOFTWARE STRUCTURE ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 5 5. SYSTEM ~ ~ ~ ROUTINES ... .... ....... .... ~ ... ~ ... 7 6. UNDERVOLTAGE MONITORING ~ 0 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ ~ 9 7. ESF BUS LOAD SEQUENCING o ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ o ~ ~ ~ ~ e ~ 10 8. AUTOTESTING ............................... 12 9. PERFORMANCE/DESIGN DEMONSTRATION TEST RESULTS . 16 10. CONCLUSION ~ ....... ........ .. ~ .. ~ ~ .. .. ~ .; ~ . 17 APPENDIX A ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ .. ... ... ~ ~ ... ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ .. ~ . ~ . ~ . ~ ~ .A-1 ESF LOAD SEQUENCER SOFTWARE VERIFICATION AND VALIDATION REPORT 1 OBJECTIVE The objective of the Software Verification and Validation Study is to verify that the software of the ESF Load Sequencer meets the requirements of the design specification, and that no sneak software paths (circuits) exist that would render the system inoperable. The ESF Load Sequencer is a module in the Balance of Plant (BOP) Engineered Safety Features Actuation System (ESFAS) supplied by General Atomic Company (GA) to the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station under Arizona Public Service Company Purchase Order 10407-13-JM-104 and Bechtel Power Corporation Speci fication 13-JM-104. This module controls loading of the station ESF bus and diesel generators under loss of power conditions or if an accident signal is present. The purpose of this report is to outline the methods used to perform this study and to detail the findings of the study. 2. STUDY PROCEDURE AND RESULTS SUMMARY The following steps were taken to per form the study: a ~ Review of Bechtel Specification (13-JM-104). -

This Book Doesn't Tell You How to Write Faster Code, Or How to Write Code with Fewer Memory Leaks, Or Even How to Debug Code at All

Practical Development Environments By Matthew B. Doar ............................................... Publisher: O'Reilly Pub Date: September 2005 ISBN: 0-596-00796-5 Pages: 328 Table of Contents | Index This book doesn't tell you how to write faster code, or how to write code with fewer memory leaks, or even how to debug code at all. What it does tell you is how to build your product in better ways, how to keep track of the code that you write, and how to track the bugs in your code. Plus some more things you'll wish you had known before starting a project. Practical Development Environments is a guide, a collection of advice about real development environments for small to medium-sized projects and groups. Each of the chapters considers a different kind of tool - tools for tracking versions of files, build tools, testing tools, bug-tracking tools, tools for creating documentation, and tools for creating packaged releases. Each chapter discusses what you should look for in that kind of tool and what to avoid, and also describes some good ideas, bad ideas, and annoying experiences for each area. Specific instances of each type of tool are described in enough detail so that you can decide which ones you want to investigate further. Developers want to write code, not maintain makefiles. Writers want to write content instead of manage templates. IT provides machines, but doesn't have time to maintain all the different tools. Managers want the product to move smoothly from development to release, and are interested in tools to help this happen more often. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,068,604 B2 Leeds Et Al

USOO8068604B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,068,604 B2 Leeds et al. (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 29, 2011 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR EVENT 2004, OO67751 A1 4/2004 Vandermeijden et al. NOTIFICATIONS 2004/O120505 A1 6/2004 Kotzin et al. 2004/0235520 A1 11/2004 Cadiz et al. 2006,0003814 A1 1/2006 Moody et al. (75) Inventors: Richard Leeds, Bellevue, WA (US); 2006/0111085 A1 5, 2006 Lee Elon Gasper, Bellevue, WA (US) 2006/0148459 A1 7/2006 Wolfman et al. 2006/01995.75 A1 9, 2006 Moore et al. (73) Assignee: Computer Product Introductions 2006/0215827 A1 9/2006 Pleging et al. 2007, OO64921 A1 3/2007 Albukerk et al. Corporation, Bellevue, WA (US) 2007/0117554 A1 5/2007 Armos (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2007/0264978 A1 1 1/2007 Stoops patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 257 days. EP O 802 661 A2 10, 1997 EP 1098 SO3 A2 5, 2001 (21) Appl. No.: 12/339,429 EP 1814, 296 A1 8, 2007 * cited by examiner (22) Filed: Dec. 19, 2008 Primary Examiner — Md S. Elahee (65) Prior Publication Data (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — LaRiviere, Grubman & US 2010/O161683 A1 Jun. 24, 2010 Payne, LLP (51) Int. Cl. (57) ABSTRACT H04M 3/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ................ 379/373.04; 379/76; 379/167.08; A method for generating a ring tone for a given caller based on 455/567 a prior conversation with that caller. -

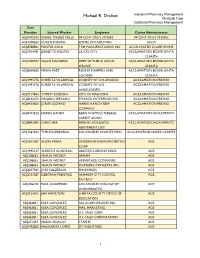

Additional Case Information

Michael R. Drobot Industrial Pharmacy Management MediLab Corp California Pharmacy Management Case Number Injured Worker Employer Claims Administrator ADJ7472102 ISMAEL TORRES VALLE 99 CENT ONLY STORES 99 CENT ONLY STORES ADJ1308567 CURTIS RIGGINS EMPIRE DISTRIBUTORS ACCA ADJ8768841 MARTIN AVILA TRM MANUFACTURING INC ACCELERATED CLAIMS IRVINE ADJ7014781 JEANETTE WILSON LA COUNTY ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA CLARITA ADJ7200937 SUSAN NAVARRO DEPT OF PUBLIC SOCIAL ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA SERVICE CLARITA ADJ8009655 MARIA PAEZ RUSKIN DAMPERS AND ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA LOUVERS CLARITA ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ACCLAMATION FRESNO ANGELES/DPSS ADJ7117844 TOMMY ROBISON CITY OF MARICOPA ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8162473 ONORIO SERRANO ESPARZA ENTERPRISES INC ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8420600 JORGE LOZANO HARRIS RANCH BEEF ACCLAMATION FRESNO COMPANY ADJ8473212 DAREN HANDY KERN SCHOOLS FEDERAL ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO CREDIT UNION ADJ8845092 CHAO HER FRESNO MOSQUITO ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO ABATEMENT DIST ADJ1361532 THELMA JENNINGS LOS ANGELES COUNTY/DPSS ACCLAMATION SANTA CLARITA ADJ1611037 ALICIA MORA ANDERSON BARROWS METALS ACE CORP ADJ1995137 ALBERTO GUNDRAN ABLESTIK LABORATORIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM RCR COMPANIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY PLUMBING CONCEPTS INC ACE ADJ2237965 JOSE CALDERON FMI EXPRESS ACE ADJ2353287 DEBORAH PRENTICE ANAHEIM CITY SCHOOL ACE DISTRICT ADJ246218 PAUL LIGAMMARI LOS ANGELES COLLEGE OF ACE CHIROPRACTIC -

MEXICAN FILM BULLETIN, Vol

THE MEXICAN FILM BULLETIN, Vol. 12 No. 8 (December 2006) The Mexican Film Bulletin Volume 12, Number 8 DeceDecembermber 2006 Miguel Aceves Mejía 19151915----20062006 Miguel Aceves Mejía is survived by his wife and son. Miguel Aceves Mejía died of pneumonia and Filmography bronchitis on 6 November 2006. Aceves Mejía, whose 1940: Rancho alegre (as part of the Trío Los Porteños) trademarks were a streak of white in his black hair and the 1947: De pecado en pecado (dubs José Pulido's singing), vocal style which earned him the nickname of "El Falsete Pecadora de Oro" or "El Rey del Falsete," was born in Chihuahua in 1950: Donde nacen los pobres November 1915 (some sources cite 1917), and first began 1951: Ella y yo, Por querer a una mujer, Nosotras las singing professionally in the 1930s in northern Mexico. sirvientas Towards the end of 1952: La mentira, Cartas a Ufemia the decade, he and 1953: Camelia two other men 1954: A los cuatro vientos formed the "Trío Los 1955: Música de siempre, Hay ángeles con espuelas, El Porteños," Águila Negra en El Vengador Solitario, Tú y las nubes, performing various Historia de un amor genres of music (the 1956: Música de siempre, Tú y la mentira, Que seas feliz!, team appeared in Que me toquen Las Golodrinas Rancho alegre in 1957: El Ciclón, Cuatro copas, Bajo el cielo de México, 1940, Aceves Rogaciano el huapangero, Guitarras de medianoche, La Mejía's film debut). feria de San Marcos, El gallo colorado, Amor se dice In the mid-1940s cantando Aceves Mejía 1958: Échame a mi la culpa!, Mi niño, mi caballo, -

Pegaso Revista Mensual M 'Ntkvideo— Uruguay

PEGASO REVISTA MENSUAL M 'NTKVIDEO— URUGUAY DIRECTOREBt Rabia de Breele-Joe* Baria Salgada m « i$2i. Nta. xxa.-Afc ni. Tres mil siglos de modas femeninas ■ Conferencia con proyecciones luminosa», leída a la Sociedad aEntre Nous», el 22 de Junio de 1MB Rompiendo el ciclo brillante de los oradores de alto vuelo que han dado a ustedes el hábito do oir :a frase; .galana que engarza el pensar profundo, y tal vez, como entremés preparatorio de temas trascendentales, un amable pedido de “ Entre Nous’’, explica la excepción qu e, significa esta charla, que deseo corta por temor de no hacerla amena., Condensar en breves momentos la evolución de la moda femenina, remontándose a través de los tiempos desdo las creaciones de Mad&me Paquin, hasta el traje... que no era traje, es seguramente ardua tarea, y las dificultades crecen si se detienen ustedes un instante a pensar en la fragilidad y sutileza del tema. L a moda, j Quién se atrevería a definirla 1 Muoho he temido que mis rudas manos de cirujano, maculasen las aterciopeladas alas de tan brillante mariposa; grande es, pues, mi audacia, pero a tenerla me han inducido la amistosa presión moral de sus actuales direotrices, y la esperanza de despertar en. ustedes el más encan tador de los defectos, femeninos: la curiosidad- i No me perdonarán ustedes, acaso, «er pesado, tal vez en demasía, si les doy la ocasión de reirse un rato de las cosas feas, con que de tiempo en tiempo la mujer transformó su divina silueta, o de admirar las creacio nes que subrayando su belleza oliéronle más anuas para vencer al hombre en esa desigual lucliá entre nuestra iusticidad y su viveza, entre la maza de Hércules y el abanico de Ninón de Léñelos? ¡Pobreeitos los hombres 1 Mientras el mundo dure, entre el cejijunto y barbudo Padre Eterno y la rubia Anadiomena retorciendo su caibeillera al nacer entre jas espumas del mar Egeo, sólo vacilarán los Bienaven turados a quienes se asegura el primer puesto en el reino de los cielos. -

2014 Top 50 Steel Roller Coasters Best of the Best!

INSIDE: Best Parks...Pages 4-13 Landscaping race...Pages 14 & 15 Shows, Events...Pages 16 & 17 Publisher’s Picks...Pages 18-20 Best New Rides...Pages 21-25 Best Rides...Pages 26-33 Wooden Coasters...Pages 34-42 TM & ©2014 Amusement Today, Inc. Steel Coasters...Pages 44-47 September 2014 | Vol. 18 • Issue 6.2 www.amusementtoday.com SeaWorld San Diego hosts 2014 Golden Ticket Awards Amusement Today presents awards in 29 categories SAN DIEGO, Calif. — In 1964, George Millay debuted SeaWorld San Diego, bring- ing us up close and personal to the experienc- 2014 es found in a marine life park. Incorporating P. GOLDEN TICKET sea life attractions and making it the focus of I. an entire day of discovery would prove to be a AWARDS success. Following this, Millay would eventual- V. BEST! ly expand SeaWorld into a chain of parks. Over BEST OF THE the years, the SeaWorld family of parks has sakes honoring our industry winners and their evolved — educating, entertaining and mov- accomplishments, but the ceremony weekend ing those that come. The number of animals has become an enjoyable networking opportu- saved and protected has been inspiring. Bring- nity full of laughter and fun, as well as a chance ing people and animals together in encounters to experience the strengths of each host park. and interactions, these are life memories peo- Like athletes in training or musicians pour- SeaWorld San Diego, celebrating its 50th anniversary this ple take home with them every day. ing their soul into their songs, the many parks season, hosted the 2014 Golden Tickets Awards, presented Rick Schuiteman, vice president of en- and water parks within the amusement indus- by Amusement Today, on Sept. -

Bibliography of Spanish Materials for Children: Kindergarten Through Grade Six

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 797 FL 002 152 AUTHOR Gonsalves, Julia, Comp.; And Others TITLE Bibliography of Spanish Materials for Children: Kindergarten Through Grade Six. INSTITUTION California State Dept. of Education, Sacramento. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW) ,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 48p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Bilingual Education, *Childrens Books, Childrens Games, Cultural Education, Dictionaries, Drama, *Elementary Education, Elementary School Students, Fles Materials, *Instructional Materials, Language Arts, Language Instruction, Language Learning Levels, Mathematics, modern Languages, Music, Reading Instruction, Social Sciences, *Spanish ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography of instructional materials, intended for students, teachers, and native speakers of Spanish, contains more than 400 items emphasizing both language and culture. The entries are arranged alphabetically in sections including: (1) books in series;(2) childrenes literature: (3) dictionaries and encyclopedias;(4) dramatization, rhymes, and poetry; (5) games, puzzles, and activities:(6) health and science; (7) mathematics; (8) music: (9) reading and language arts, and (10) social science. Bibliographic information includes the price of the publication, availability, and suggested readership. Appendixes contain a directory of publishers and distributors, and a book evaluation form. (RL) ii 1 DEPAINISNI Off MIN. MEADOW I MAW :. WM Of SWOON THIS DOtuNENI MS WEN WPRODOCED EXACTiv IS RELAYED 12014THE PERSON OR OmonsuOi ORMOND IIPOINtS OF VOW OR OPINIONS Wile DO NOT NKOSI,OR MVO (NNW OM OF INIFAIION 'NOON ON POIWy %MO I 8 A Kindergarten Through Grade Six CALIFORNIA STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Wilson Riles Superintenden. of Public Instruction Sacramento 1971 I lb This publication, which was funded under pro- visions of the National Defense Education Act, Tide ill, was edited and prepared for photo-offset production by the Bureau of Publications, Call. -

System Update Alt Download

GXGIYDFGAC ^ Wooden roller coasters ^ PDF Wooden roller coasters By Source Reference Series Books LLC Jun 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x7 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 71. Chapters: Wooden roller coaster, El Toro, Son of Beast, Coney Island Cyclone, Derby Racer, Crystal Beach Cyclone, Zippin Pippin, The Beast, American Eagle, Lightning, Dragon Coaster, Rolling Thunder, Scenic Railway Roller Coaster, Timber Wolf, The Comet, Rampage, Thunderbolt, The Voyage, Gwazi, Phoenix, Colossus, Yankee Cannonball, Thunder Road, Wild Mouse, Lightning Racer, Grizzly, White Cyclone, Prowler, Big Dipper, Mega Zeph, Thunderhead, The Racer, Giant Dipper, Viper, Scooby-Doo's Ghoster Coaster, Leap-The-Dips, Silver Comet, Shivering Timbers, The Raven, The Bush Beast, Flying Turns, Twister, T Express, Apocalypse, American Thunder, Tornado, Cornball Express, Thunderhawk, Blue Streak, Woodstock Express, Switchback Railway, The Wild One, Twister II, Wild Cat, Mighty Canadian Minebuster, Rebel Yell, Psyclone, Boulder Dash, The Great American Scream Machine, The Legend, Hades, Jack Rabbit, Villain, Balder, Vuoristorata, Ravine Flyer II, Wildcat, Grand National, Hurler, Arkansas Twister, Rattler, Renegade, Texas Cyclone, Mean Streak, Nickelodeon Streak, The Bobs, Kentucky Rumbler, Hoosier Hurricane, Pegasus, Wild Beast, Colossos, Cheetah, Skyliner, Cyclops, Wolverine Wildcat, Megafobia, Zach's Zoomer, Jetstream, Zeus, Cannon Ball, Bandit, Le Monstre, Raging Wolf Bobs, Zipper Dipper, Ozark Wildcat, Hercules, Dania Beach Hurricane, Twisted Twins, High Roller,... READ ONLINE [ 3.09 MB ] Reviews Completely among the finest pdf I actually have ever read through. it was actually writtern extremely completely and beneficial. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. -- Santos Metz It is an amazing ebook i have possibly study.