England's Smaller Seaside Towns: a Benchmarking Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Coast Management Plan, 3Rd Review

North Yorkshire and Cleveland Heritage Coast Management Plan, 3rd Review HERITAGE COAST North Yorkshire & Cleveland markdentonphotographic.co.uk www. photograph: North Yorkshire and Cleveland Heritage Coast Contents Management Plan, 3rd Review STRATEGY Background 3 National Objectives for Heritage Coasts 3 2008 - 2013 National Targets for Heritage Coasts 4 Heritage Coast Organisation 4 Heritage Coast Boundary 6 Co-ordination of Work 6 Staffing Structure and Issues 6 Monitoring and Implementation 7 Involvement of Local People in Heritage Coast Work 7 Planning Policy Context 8 Relationship with other Strategies 9 Protective Ownership 9 CONSERVATION Landscape Conservation and Enhancement 10 Natural and Geological Conservation 10 Village Enhancement and the Built Environment 11 Archaeology 12 PUBLIC ENJOYMENT AND RECREATION Interpretation 14 Visitor and Traffic Management 15 Access and Public Rights of Way 16 HERITAGE COAST Tourism 16 North Yorkshire & Cleveland HEALTH OF COASTAL WATERS & BEACHES Litter 17 Beach Awards 17 Water Quality 18 OTHER ISSUES Coastal Defence and Natural Processes 19 Renewable Energy, Off Shore Minerals and Climate Change 19 ACTION PLAN 2008 - 2013 20-23 Heritage Coast - a coastal partnership financially supported by: Appendix 1 - Map Coverage 24-32 Printed on envir0nmentally friendly paper Published by North Yorkshire and Cleveland Coastal Forum representing the North York Moors © North York Moors National Park Authority 2008 National Park Authority, Scarborough Borough Council, North Yorkshire County Council, www.coastalforum.org.uk -

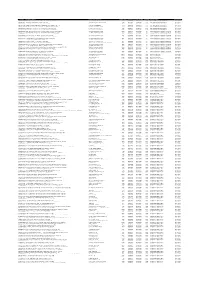

Prop Ref Full Property Address Primary Liable Party Name

Prop Ref Full Property Address Primary Liable party name Rateable Value Account Ref Account Start date Relief Type Relief Description Relief Start Date 102009050600 36, Bridlington Street, Hunmanby, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0JR Yorkshire Wildlife Trust Ltd 900 100902707 01/04/1990 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 103038750560 18, John Street, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9DQ The Cambridge Centre (S.A.D.A.C) Ltd 11250 101540647 27/06/1997 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 103086250500 Car Park, Wharfedale, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0DG Home Group Ltd 8000 700078619 01/05/2013 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 104025750540 Builders Yard, Main Street, Flixton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3UB Groundwork Wakefield Ltd 21500 700078709 01/06/2013 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 108045150555 Adj 116, Main Street, Cayton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3RP Yorkshire Coast Homes Limited 11500 700080167 17/04/2014 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 109045450540 33, Main Street, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4PS Next Choice (Yorkshire) Ltd 4950 700082311 01/06/2014 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 117074150505 9, Station Road, Snainton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO13 9AP Scarborough Theatre Trust Ltd 53000 700082857 12/01/2015 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 124052050500 Cober Hill, Newlands Road, Cloughton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO13 0AR Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 15000 700056775 14/01/2000 DI DISCRETIONARY -

Sit Back and Enjoy the Ride

MAIN BUS ROUTES PLACES OF INTEREST MAIN BUS ROUTES Abbots of Leeming 80 and 89 Ampleforth Abbey Abbotts of Leeming Arriva X4 Sit back and enjoy the ride Byland Abbey www.northyorkstravel.info/metable/8089apr1.pdf Arriva X93 Daily services 80 and 89 (except Sundays and Bank Holidays) - linking Castle Howard Northallerton to Stokesley via a number of villages on the Naonal Park's ENJOY THE NORTH YORK MOORS, YORKSHIRE COAST AND HOWARDIAN HILLS BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT CastleLine western side including Osmotherley, Ingleby Cross, Swainby, Carlton in Coaster 12 & 13 Dalby Forest Visitor Centre Cleveland and Great Broughton. Coastliner Eden Camp Arriva Coatham Connect 18 www.arrivabus.co.uk Endeavour Experience Serving the northern part of the Naonal Park, regular services from East Yorkshire 128 Middlesbrough to Scarborough via Guisborough, Whitby and many villages, East Yorkshire 115 Flamingo Land including Robin Hood's Bay. Late evening and Sunday services too. The main Middlesbrough to Scarborough service (X93) also offers free Wi-Fi. X4 serves North Yorkshire County Council 190 Filey Bird Garden & Animal Park villages north of Whitby including Sandsend, Runswick Bay, Staithes and Reliance 31X Saltburn by the Sea through to Middlesbrough. Ryedale Community Transport Hovingham Hall Coastliner services 840, 843 (Transdev) York & Country 194 Kirkdale and St. Gregory’s Minster www.coastliner.co.uk Buses to and from Leeds, Tadcaster, Easingwold, York, Whitby, Scarborough, Kirkham Priory Filey, Bridlington via Malton, Pickering, Thornton-le-Dale and Goathland. Coatham Connect P&R Park & Ride Newburgh Priory www.northyorkstravel.info/metable/18sep20.pdf (Scarborough & Whitby seasonal) Daily service 18 (except weekends and Bank Holidays) between Stokesley, Visitor Centres Orchard Fields Roman site Great Ayton, Newton under Roseberry, Guisborough and Saltburn. -

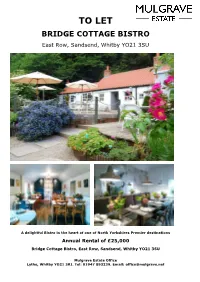

TO LET BRIDGE COTTAGE BISTRO East Row, Sandsend, Whitby YO21 3SU

TO LET BRIDGE COTTAGE BISTRO East Row, Sandsend, Whitby YO21 3SU A delightful Bistro in the heart of one of North Yorkshires Premier destinations Annual Rental of £25,000 Bridge Cottage Bistro, East Row, Sandsend, Whitby YO21 3SU Mulgrave Estate Office Lythe, Whitby YO21 3RJ. Tel: 01947 893239. Email: [email protected] This prime location Bistro lies in the heart of Sandsend, one of the Yorkshire Coast’s most desirable locations. • Unit Extends to c.93m2 (1,000 SQ FT) plus outside dining areas • Rent £25,000 Per Annum • Potentially suited for other uses STP • Central location and adjacent to the main village amenities • On-site parking for staff This is a rare and exciting Café/Bistro/Restaurant opportunity in the tourist hot spot of Sandsend. The property currently operates as a highly regarded and popular Bistro but has the potential to offer more. The main dining areas cover circa 30 people and the large south facing garden area offers further potential during the key tourism season. Other uses, such as retail, would be considered but may be subject to planning consent. Location: Sandsend is an established and very popular destination on the Yorkshire Coast. The sandy beach and its proximity to the historic port of Whitby and the North York Moors National Park, make Sandsend the vibrant hub that it is. The Estate has further plans to enhance the locality with more retail opportunities, enlarged car parking facilities and eateries in the next few years. Whitby is 2.5miles, Scarborough 22miles and York 48miles. Accommodation: The property comprises of 2 dining areas, bar area, serving area, main kitchen, preparation kitchen area and 2 WC’s. -

Archaeological Excavation and Survey of Scheduled Coastal Alum Working Sites at Boulby, Kettleness, Sandsend and Saltwick, North Yorkshire

Archaeological Excavation and Survey of Scheduled Coastal Alum Working Sites at Boulby, Kettleness, Sandsend and Saltwick, North Yorkshire ARS Ltd Report No-2015/42 OASIS No: archaeol5-208500 Compiled By: Samantha Bax, Rupert Lotherington PCIfA and Dr Gillian Scott Archaeological Research Services Ltd The Eco Centre Windmill Way Hebburn Tyne and Wear NE31 1SR Checked By: Chris Scott MCIfA Tel: 0191 4775111 [email protected] www.archaeologicalresearchservices.com Archaeological Excavation and Survey of Coastal Alum Working Sites at Boulby, Kettleness, Sandsend and Saltwick, North Yorkshire Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................. 3 List of Tables .............................................................................................................. 7 Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 8 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 11 2 Results ............................................................................................................... 16 3 Specialist reports ..............................................................................................101 4 Discussion .........................................................................................................105 5 Publicity, Confidentiality and Copyright ............................................................118 -

EIA Scoping Report Penwortham Mill and Former Sumpter Horse Pub Site Delta-Simons Project Number 19-0864

EIA Scoping Report Penwortham Mill and former Sumpter Horse Pub Site Delta-Simons Project Number 19-0864 EIA Scoping Report Wood Farm, Ruskington, Sleaford, NG34 9SL Presented to Stonegate Farmers Ltd Issued: March 2021 Delta-Simons Project No. 21-0130 Environment | Health & Safety | Sustainability EIA Scoping Report Wood Farm, Ruskington, Sleaford, NG34 9SL Delta-Simons Project Number 21-0130 Report Details Client Stonegate Farmers Ltd Report Title EIA Scoping Report Site Address Wood Farm, Ruskington, Sleaford, NG34 9S Project No. 21-0130 Delta-Simons Contact Alison Yarrow Quality Assurance Issue Issue Technical Status Comments Author Authorised No. Date review 18th March 1 Final 2021 Various Alison Yarrow Alison Yarrow Collated by Technical Technical Evie Scott Director Director Consultant About us Delta-Simons is a trusted, multidisciplinary environmental consultancy, focused on delivering the best possible project outcomes for customers. Specialising in Environment, Health & Safety and Sustainability, Delta-Simons provide support and advice within the property development, asset management, corporate and industrial markets. Operating from ten locations - Lincoln, Birmingham, Bristol, Dublin, Leeds, London, Manchester, Newcastle, Norwich and Nottingham - we employ over 100 environmental professionals, bringing experience from across the private consultancy and public sector markets. Delta-Simons is proud to be a founder member of the Inogen® Environmental Alliance, a global corporation providing multinational organisations with consistent, -

Ammonite Fields Forever: from the Jurassic Coast to Collecting on the Beaches of North Yorkshire, England

Ammonite Fields Forever: From the Jurassic Coast to collecting on the beaches of North Yorkshire, England by Rhonda Gates Once upon a time, just at the brink of an unfathomable and devastating year of death, anxiety, isolation and trauma caused by Covid19, four friends set aside their LRB hats for new hats: they became “Yorkies” and set out to collect fossils on the UK’s North Yorkshire Jurassic coastline generally and inclusively referred to as Whitby. This is the retelling of that adventure, “Ammonite Fields Forever: From the Jurassic Coast to collecting on the beaches of North Yorkshire, England” with Marie Angkuw, Deborah Lovely, Andrew Young and me, Rhonda Gates. ___ The dreaming of this trip began on the flight back from Lyme Regis in early March of 2019. The actual planning for this adventure began a few weeks later in April, once the 2020 tide tables were published. We then spent the next 10 months locking in airfare, our airbnb, researching and purchasing gear, and reading every book and online site we could find. Friends in Lyme Regis had mentioned that it would be very strenuous, with at least one site requiring a rope to get down to and back up from the beach. However, our friends had seen us in action collecting at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, so they assured us we could handle it if we prepared for it. So the next 10 months were also spent “in Whitby fossil-hunting training mode” which required building up upper body strength and embracing every set of stairs and hill in our path. -

Sowing the Seeds for Growth GREATER LINCOLNSHIRE

Sowing the Seeds for Growth GREATER LINCOLNSHIRE Contents 3 Linking Greater Lincolnshire 12 Engineering and Science to the rest of the world – Growth From the Start National Centre for Food 4 Introduction Manufacture 5 Food Production Frontier Branston Ltd Tong Peal Freshtime 15 The Supply Chain 7 Manufacturing Ports of Grimsby and – Creating the Products Immingham Moy Park Rail Freight Interchange Young’s Seafood Ltd Distribution Opportunities 9 Packaging the Product The Supply Chain Initiative Coveris Clugstons Optima Design 19 Advice and Support 11 Room to Grow – Development Opportunities 2 SOWING THE SEEDS FOR GROWTH Greater Lincolnshire: The Wise Business Choice Food has long been synonymous with Greater area. Whether you’re a new start-up looking to invest Lincolnshire, be it our long and rich history of in an expanding area or tap into the well established growing the nation’s favourite produce, or world- supply chain, or a larger firm hoping to take advantage class manufacturers and packagers choosing to of new developments, there’s something for you in locate their business here. Greater Lincolnshire. I know that the area is fortunate to have one of the Our geographical location is also second to none; UK’s largest and most progressive food sectors, with not only do we offer a wealth of opportunities for dynamic businesses and a well qualified workforce. businesses, the lifestyle outside of work is enviable. The industry contributes an estimated £2.5 billion Greater Lincolnshire boasts wide open spaces, low to Greater Lincolnshire’s economy and is the third property prices, a good transport network, historical biggest sector in terms of value and employment, with attractions, a bustling waterfront in Lincoln city centre around 56,000 people working in agriculture or food – listed as one of the best place to live by the Sunday production. -

Thordisa House Sandsend, Whitby, North Yorkshire Thordisa House East Row, Sandsend, Whitby, North Yorkshire YO21 3SU

Thordisa House Sandsend, Whitby, North Yorkshire Thordisa House East Row, Sandsend, Whitby, North Yorkshire YO21 3SU Once in a generation opportunity to acquire what is probably the best house on the North Yorkshire coast Reception hall • 2 further reception rooms • study kitchen/breakfast room • utility room • pantry WCs • 5 bedrooms • 2 bathrooms • 4 loft rooms Coal store • attached store • greenhouse Coachouse and garaging In all over one acre Freehold for sale Sandsend is a coastal village on North Yorkshire’s heritage coast known for its long white sandy beach that stretches to Whitby, and its own bay sheltered from the northwest by cliffs. It is highly probable that in Viking times the entire settlement was known as Thordisa, meaning the beck of a woman named Thordis. Available for the first time in generations, Thordisa House is certainly the most distinguished along this stretch of coast. Its history stretches back a few hundred years with its early eighteenth century origins extended over generations: in the early 20th century with large bay windows; and later with a fine stone extension incorporating mullion windows and French doors. Now in need of renovation, this coastal house with its barn and extensive private gardens represents a once in a generation opportunity for an incoming buyer. • Detached family house of 4156 sq ft arranged over three floors • Discreetly situated behind a high stone wall in a private no-through lane within a quintessential English seaside village • Western outlook towards the arc of the sun, overlooking -

Fossils of the Whitby Coast: a Photographic Guide Whitby Coast a Photographic Guide

Dean R. Lomax Fossils of the Fossils of the Whitby coast: A photographic guide A Whitby coast: Fossils of the Whitby coast A photographic guide Dean R. Lomax The small coastal town of Whitby is located in North Yorkshire, England. It has been associated with fossils for hundreds of years. From the common ammonites to the spectacular marine reptiles, a variety of fossils await discovery. This book will help you to identify, understand and learn about the fossils encountered while fossil hunting along this stretch of coastline, bringing prehistoric Whitby back to life. It is illustrated in colour throughout with many photographs of fossil specimens held in museum and private collections, in addition to detailed reconstructions of what some of the extinct organisms may have looked like in life. As well as the more common species, there are also sections on remarkable finds, such as giant plesiosaurs, marine crocodilians and even pterosaurs. The book provides information on access to the sites, how to identify true fossils from pseudo fossils and even explains the best way of extracting and preparing fossils that may be encountered. This guide will be of use to both the experienced fossil collector and the absolute beginner. Take a step back in time at Whitby Siri Scientific Press and see what animals once thrived here during the Jurassic Period. More than 200 colour photographs and illustrations Photography by Benjamin Hyde and Illustrations by Nobumichi Tamura Siri Scientific Press © Dean Lomax and Siri Scientific Press 2011 © Dean Lomax -

Authority No. Dppos Alnwick District Council 2 Alnwick - 10/08/2007, Amble - 10/08/2007

The following table outlines those authorities that have published Designation Orders as at 1st November 2010. Please note that if you require full name of roads in an area, you should contact the relevant council office. Authority No. DPPOs Alnwick District Council 2 Alnwick - 10/08/2007, Amble - 10/08/2007. Amber Valley Borough 13 Belper - 24/05/2004, Oakerthorpe - 24/05/2004, Ripley and Heanor - 16/07/2004, Belper Railway Station - 24/01/2005, Council Church St Recreation Ground, Danesby Rise Recreation Ground, Denby Institute Recreation Ground, Denby - 05/12/2005, Festival Gardens, Belper - 22/06/2006, Kilburn - 08/09/2006, John Flamstead Memorial Park, Denby - 06/08/2007, Somercotes and Leabrooks - 06/08/2007, Belper Park - 06/12/2007, Heanor, various - 29/08/2008, Swanwick - 18/09/2009, Aldercar Rec Ground, Queen Street Rec Ground, Footpath between Queen Street and Acorn Centre - 16/07/2010. Isle of Anglesey County 3 Holyhead Town - 01/02/2005, Town of Llangefni - 15/12/2005, Menai Bridge Town - 01/08/2007. Council Arun District Council 1 Bognor Regis and Littlehampton, various - 01/06/2006. Aylesbury Vale District 2 Aylesbury various - 31/07/2008, Winslow and Steeple Claydon - 29/05/2009 Council Barking & Dagenham 2 Barking Town centre - 20/12/2004, Rainham Road South - 24/11/2008. Borough Council, London Borough of Barnet Borough Council, 3 North Finchley Town Centre - 01/03/2004, Hendon Central - 01/03/2004, Finchley Church End Town Centre - 01/03/2004. London Borough of Barnsley Metropolitan 15 Wombwell Town Centre - 03/04/2004, -

10 Year Replacement Programme

House MAIN ROOF HEATING UPRN Number Street 1 Street 2 COVERING BATHROOM KITCHEN BOILER SYSTEM 505250010 1 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2014 505250020 2 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2014 505250030 3 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 505250040 4 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 505250050 5 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2014 505250060 6 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2014 505250070 7 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2014 2014 505250080 8 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 2016 505250090 9 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 505250100 10 PRINCESS SQUARE ANWICK 505300230 2 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300020 3 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2019 2018 505300240 4 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300250 6 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300040 7 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300050 9 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300060 11 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300280 12 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300290 14 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2014 505300080 15 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300090 17 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300310 18 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2019 505300100 19 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300320 20 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300110 21 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505300330 22 RIVER LANE ANWICK 505300120 23 RIVER LANE ANWICK 2021 2019 505350100 21 SCHOOL CRESCENT ANWICK 2018 507050030 3 CHURCH AVENUE ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2019 2021 507050040 4 CHURCH AVENUE ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2019 House MAIN ROOF HEATING UPRN Number Street 1 Street 2 COVERING BATHROOM KITCHEN BOILER SYSTEM 507050100 10 CHURCH AVENUE ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2019 507050110 11 CHURCH AVENUE ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2019 507110510 20 MAIN STREET ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2021 2014 2014 507110520 22 MAIN STREET ASHBY DE LA LAUNDE 2021 2014 2014 507110100