Ammonite Fields Forever: from the Jurassic Coast to Collecting on the Beaches of North Yorkshire, England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Coast Management Plan, 3Rd Review

North Yorkshire and Cleveland Heritage Coast Management Plan, 3rd Review HERITAGE COAST North Yorkshire & Cleveland markdentonphotographic.co.uk www. photograph: North Yorkshire and Cleveland Heritage Coast Contents Management Plan, 3rd Review STRATEGY Background 3 National Objectives for Heritage Coasts 3 2008 - 2013 National Targets for Heritage Coasts 4 Heritage Coast Organisation 4 Heritage Coast Boundary 6 Co-ordination of Work 6 Staffing Structure and Issues 6 Monitoring and Implementation 7 Involvement of Local People in Heritage Coast Work 7 Planning Policy Context 8 Relationship with other Strategies 9 Protective Ownership 9 CONSERVATION Landscape Conservation and Enhancement 10 Natural and Geological Conservation 10 Village Enhancement and the Built Environment 11 Archaeology 12 PUBLIC ENJOYMENT AND RECREATION Interpretation 14 Visitor and Traffic Management 15 Access and Public Rights of Way 16 HERITAGE COAST Tourism 16 North Yorkshire & Cleveland HEALTH OF COASTAL WATERS & BEACHES Litter 17 Beach Awards 17 Water Quality 18 OTHER ISSUES Coastal Defence and Natural Processes 19 Renewable Energy, Off Shore Minerals and Climate Change 19 ACTION PLAN 2008 - 2013 20-23 Heritage Coast - a coastal partnership financially supported by: Appendix 1 - Map Coverage 24-32 Printed on envir0nmentally friendly paper Published by North Yorkshire and Cleveland Coastal Forum representing the North York Moors © North York Moors National Park Authority 2008 National Park Authority, Scarborough Borough Council, North Yorkshire County Council, www.coastalforum.org.uk -

Prop Ref Full Property Address Primary Liable Party Name

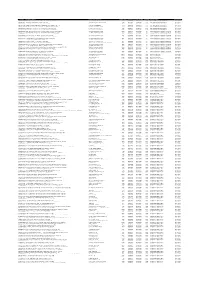

Prop Ref Full Property Address Primary Liable party name Rateable Value Account Ref Account Start date Relief Type Relief Description Relief Start Date 102009050600 36, Bridlington Street, Hunmanby, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0JR Yorkshire Wildlife Trust Ltd 900 100902707 01/04/1990 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 103038750560 18, John Street, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9DQ The Cambridge Centre (S.A.D.A.C) Ltd 11250 101540647 27/06/1997 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 103086250500 Car Park, Wharfedale, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0DG Home Group Ltd 8000 700078619 01/05/2013 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 104025750540 Builders Yard, Main Street, Flixton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3UB Groundwork Wakefield Ltd 21500 700078709 01/06/2013 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 108045150555 Adj 116, Main Street, Cayton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3RP Yorkshire Coast Homes Limited 11500 700080167 17/04/2014 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 109045450540 33, Main Street, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4PS Next Choice (Yorkshire) Ltd 4950 700082311 01/06/2014 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 117074150505 9, Station Road, Snainton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO13 9AP Scarborough Theatre Trust Ltd 53000 700082857 12/01/2015 DI20 20% DISCRETIONARY TOP UP RELIEF 01/04/2016 124052050500 Cober Hill, Newlands Road, Cloughton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO13 0AR Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 15000 700056775 14/01/2000 DI DISCRETIONARY -

Yorkshire-Coast--Moorland-Scenes

Produced by Ted Garvin, Ginny Brewer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team YORKSHIRE COAST AND MOORLAND SCENES Painted and Described By GORDON HOME _Second Edition_ 1907 _First Edition published April 26, 1904 Second Edition published April, 1907_ PREFACE page 1 / 92 It may seem almost superfluous to explain that this book does not deal with the whole of Yorkshire, for it would obviously be impossible to get even a passing glimpse of such a great tract of country in a book of this nature. But I have endeavoured to give my own impressions of much of the beautiful coast-line, and also some idea of the character of the moors and dales of the north-east portion of the county. I have described the Dale Country in a companion volume to this, entitled 'Yorkshire Dales and Fells.' GORDON HOME. EPSOM, 1907. CONTENTS CHAPTER I ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY CHAPTER II ALONG THE ESK VALLEY CHAPTER III THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR page 2 / 92 CHAPTER IV THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER V SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER VI WHITBY CHAPTER VII THE CLEVELAND HILLS CHAPTER VIII GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY CHAPTER IX FROM PICKERING TO RIEVAULX ABBEY LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. On Barnby Moor 2. Goathland Moor 3. An Autumn Scene on the Esk page 3 / 92 4. Sleights Moor from Swart Houc Cross 5. A Stormy Afternoon 6. East Row, Sandsend 7. In Mulgrave Woods 8. Runswick Bay 9. A Sunny Afternoon at Runswick 10. Sunrise from Staithes Beck 11. Three Generations at Staithes 12. -

Geology of the Yorkshire Coast 4. Staithes

05/03/2013 Geology of the Yorkshire Coast Dr Liam Herringshaw - [email protected] 4. Staithes – of Sand and Iron Early Jurassic Staithes Sandstone Formation Cleveland Ironstone Formation 1 05/03/2013 Staithes to Old Nab Simplified cliff section Rocks get younger towards south and east: RMF-SSF-CIF-WMF 2 05/03/2013 Staithes Sandstone Formation •Early Jurassic: Middle Pliensbachian Key features Sandstones with cross-stratification Burrowed siltstones 3 05/03/2013 Hummocky cross-stratification Fine-grained storm deposits 4 05/03/2013 Burrowed siltstones •After each storm, organic-rich silts deposited in quieter conditions Cleveland Ironstone Formation Transition from SSF to CIF, Penny Nab 5 05/03/2013 Oolitic ironstones Cleveland Ironstone Formation Modern oolites Warm, wave-agitated waters 6 05/03/2013 Stratigraphy Fossils 7 05/03/2013 Old Nab Ironstone burrows 8 05/03/2013 Siderite – iron carbonate Grows in sediment Needs low oxygen, low-sulphide conditions with iron and calcium Normally grey; turns red when oxidized Cleveland ironstone environment Fossils = marine conditions Ooids = high energy environment Primary iron-rich ooids = iron-rich waters Burrow scratches = firm sediments Shallow sea, wave-agitated, lots of runoff from land (with iron-rich soils?) 9 05/03/2013 Jet-powered Whitby Early Jurassic Whitby Mudstone Formation Grey Shales Black Shales Alum Shales Whitby Mudstone Formation 10 05/03/2013 Whitby Mudstone Formation Late Early Jurassic – Toarcian 5 subdivisions, mostly muddy Common features - sediments Finely laminated, -

Yorkshire Painted and Described

Yorkshire Painted And Described Gordon Home Project Gutenberg's Yorkshire Painted And Described, by Gordon Home This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Yorkshire Painted And Described Author: Gordon Home Release Date: August 13, 2004 [EBook #9973] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Michael Lockey and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED BY GORDON HOME Contents CHAPTER I ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY CHAPTER II ALONG THE ESK VALLEY CHAPTER III THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR CHAPTER IV THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER V Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER VI WHITBY CHAPTER VII THE CLEVELAND HILLS CHAPTER VIII GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY CHAPTER IX FROM PICKERING TO RIEVAULX ABBEY CHAPTER X DESCRIBES THE DALE COUNTRY AS A WHOLE CHAPTER XI RICHMOND CHAPTER XII SWALEDALE CHAPTER XIII WENSLEYDALE CHAPTER XIV RIPON AND FOUNTAINS ABBEY CHAPTER XV KNARESBOROUGH AND HARROGATE CHAPTER XVI WHARFEDALE CHAPTER XVII SKIPTON, MALHAM AND GORDALE CHAPTER XVIII SETTLE AND THE INGLETON FELLS CHAPTER XIX CONCERNING THE WOLDS CHAPTER XX FROM FILEY TO SPURN HEAD CHAPTER XXI BEVERLEY CHAPTER XXII ALONG THE HUMBER CHAPTER XXIII THE DERWENT AND THE HOWARDIAN HILLS CHAPTER XXIV A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE CITY OF YORK CHAPTER XXV THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICT INDEX List of Illustrations 1. -

Register of Licensed Caravan Sites CARAVAN LICENCE NAME of SITE ADDRESS of SITE NUMBER

Register of Licensed Caravan Sites CARAVAN LICENCE NAME OF SITE ADDRESS OF SITE NUMBER Primrose Valley, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 001 Primrose Valley Holiday Village 9RF 002 Blue Dolphin Holiday Park Gristhorpe, Filey, YO14 9PU Howlgate Lane, Newholm, Whitby, YO21 004 Newholm Green Caravan Site 3QU Ladycross Plantation Caravan 005 Site Egton, Whitby, YO21 1UA East Keld Farm, Robin Hoods Bay, Whitby, 006 East Keld Farm Caravans YO22 4PE 007 Jacobs Mount Caravan Park Stepney Road, Scarborough, YO12 5NL 008 Muston Grange Caravan Park Muston Road, Filey, YO14 0HU Killerby on the Cliff Caravan Killerby House, Killerby Cliff, Cayton Bay, 009 Site Scarborough, YO11 3NR Lythe Caravan and Camping 010 Site High Street, Lythe, Whitby, YO21 3RT Rear of Bank Foot Cottage Land to Rear of Bank Foot Cottage, Ellerby, 011 Caravan Site (OS Field 7953) Saltburn, TS13 5HS 012 Glen Esk Caravan Site Larpool Lane, Ruswarp, Whitby, YO22 4NE Limestone Road, Burniston, Scarborough, 013 Applegrove Country Park YO13 0DD Mill Lane, Cayton Bay, Scarborough, YO11 014 Cayton Bay Holiday Park 3NN The Coach House, 53 Rosedale Lane, Port 015 Coach House Caravan Park Mulgrave, Saltburn, TS13 5LD Clarendon House Caravan Rear of 42 Hinderwell Lane, Runswick Bay, 017 Park Saltburn, TS13 5HR Abbots House Farm Camping Abbots House, Goathland, Whitby, YO22 018 and Caravan Site 5NH Airy Hill Farm, Prospect Hill, Whitby, YO21 019 Airy Hill Farm Caravan Site 1QD Larpool Hall, Larpool Drive, Whitby, YO22 020 Larpool Hall Caravan Site 4JE 021 Lowfield Farm Caravan Park Bridlington -

Partial Measures’ Survey 2015

Cell 1 Regional Coastal Monitoring Programme Update Report 7: ‘Partial Measures’ Survey 2015 Scarborough Council Final Report July 2015 Contents Disclaimer ................................................................................................................................. i Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................... ii Water Levels Used in Interpretation of Changes ..................................................................... ii Glossary of Terms ................................................................................................................... iii Preamble ................................................................................................................................. iv 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Study Area ................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 1 2. Analysis of Survey Data ................................................................................................. 11 2.1 Staithes ...................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Runswick Bay ............................................................................................................ -

FOIA2062 Response Please Find Attached to This E-Mail an Excel Spreadsheet Detailing the Current Recipients of Mandatory Charity

FOIA2062 Response Please find attached to this e-mail an excel spreadsheet detailing the current recipients of mandatory charity relief from Scarborough Borough Council in respect of Business Rates. Relief Award Primary Liable party name Full Property Address Start Date Filey Museum Trustees 8 - 10, Queen Street, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9HB 04/01/1997 Filey Sea Cadets, Southdene Pavilion, Southdene, Filey, North Filey Sea Cadets Yorkshire, YO14 9BB 04/01/1997 Endsleigh Convent, South Crescent Road, Filey, North Institute Of Our Lady Of Mercy Yorkshire, YO14 9JL 04/01/1997 Filey Cancer Fund 31a, Station Road, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 9AR 04/01/1997 Yorkshire Wildlife Trust Ltd Car Park, Wharfedale, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0DG 04/01/1997 Village Hall, Filey Road, Flixton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, Folkton & Flixton Village Hall YO11 3UG 04/01/1997 Muston Village Hall Village Hall, Muston, Filey, North Yorkshire, YO14 0HX 04/01/1997 Jubilee Hall, 133-135, Main Street, Cayton, Scarborough, North Cayton Jubilee Hall Yorkshire, YO11 3TE 04/01/1997 Hall, North Lane, Cayton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 Cayton Village Hall 3RZ 04/01/1997 Memorial Hall, Main Street, Seamer, Scarborough, North Seamer & Irton War Memorial Hall Yorkshire, YO12 4QD 04/01/1997 Hall, Moor Lane, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 Derwent Valley Scout Group 4RW 04/01/1997 Village Hall, Wilsons Lane, East Ayton, Scarborough, North Ayton Village Hall Yorkshire, YO13 9HY 04/01/1997 Village Hall, Cayley Lane, Brompton-By-Sawdon, Scarborough, Brompton Village Hall Committee North Yorkshire, YO13 9DL 04/01/1997 42nd St Marks Scout Group 120, Coldyhill Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 6SD 04/01/1997 Burniston & Cloughton V. -

RUNSWICK BAY a Pleasant Walk Along the Cliff Top with Wide Views Over Runswick Bay

access walks RUNSWICK BAY A pleasant walk along the cliff top with wide views over Runswick Bay. This walk has a maximum gradient of 1 in 20. It is likely to be suitable for people with impaired mobility or with a pushchair, wheelchair or mobility scooter. The walk has no steps or stiles. Conditions will vary depending on the recent weather conditions. Distance Route Points of interest This is a linear walk returning by the Walk back along the road from the car The view from the car park extends same route. The total distance is park and turn right at The Runswick Bay over the wide sweep of Runswick Bay 1.2 miles (2km) Hotel. Follow the Cleveland Way to the to Kettleness. The bay is one of the few cliff edge and turn left. Follow the path sandy bays with easy access and is Path details through two fi elds before returning. popular for water sports. At Point 6 on the walk you pass a pond which was Mainly fl at with slight rises. The surface Nearest Facilities is a hard limestone aggregate or short created as a reservoir to supply water The nearest accessible toilets are grass, which can be a bit bumpy to an old iron works situated part way at Staithes Top car park. There are in places. down the nearby cliff. refreshments available at Cliffemount Hotel & Runswick Bay Hotel, both near Start the start of the walk. Start the walk from the Pay & Display car park at the top of the village (Map OS How to get there Outdoor Leisure 27 Grid Ref: 808162) Turn off the A174 Whitby – Saltburn road for Runswick Bay. -

![Modernising Trust Ports [Second Edition] I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9509/modernising-trust-ports-second-edition-i-749509.webp)

Modernising Trust Ports [Second Edition] I

Modernising Trust Ports [second edition] i. Introduction This is the second edition of Modernising Trust Ports (MTP). The first was published in 2000 by the then Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, and followed a review of the trust ports sector that focused principally on corporate governance and accountability. That review highlighted a need for a general improvement in the openness and accountability with which trust ports conduct their business, and prompted the Department to stipulate governance guidelines which it expected all trust port boards to use as the benchmark of best practice — Modernising Trust Ports. A similar exercise was undertaken with respect to municipal ports. The general improvement sought by the Government has been widely in evidence in the years since then, and the sector should be congratulated for the considerable strides it has taken in this direction. In 2006 the successor Department for Transport embarked upon a thorough review of ports policy, in light of devolution in the UK planning and political systems, and the evolution of global trading patterns. The review looked among other things at the future of the mixed ports sector, including the outlook for trust ports in the coming decades. This was set against the backdrop of the decision by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) in 2001 to classify the largest trust ports as public corporations, which had the effect of placing those ports’ borrowing on the Department’s accounts, and the relevant ports' subsequent applications, now on hold, to remove themselves from perceived public sector controls through the pursuit of appropriate Harbour Revision Orders (HROs). -

Heritage Coast Leaflet

seo ih OBPartnership AONB Wight of Isle Hamstead Tennyson & ɀ The wildlife reflects the tranquil nature of the landscape – the wildlife and habitats that thrive Hamstead here are susceptible to disturbance, please respect this – please stay on the paths and avoid lighting fires or barbeques. Heritage Coasts ɀ Fossils are easy to find amongst the beach gravel. Look for flat, black coloured pieces of turtle The best and most valued parts of the coastlines of shell, after you have found these start looking for England and Wales have been nationally recognised teeth and bones. through the Heritage Coast accolade. ɀ Hamstead Heritage Coast Birds such as teal, curlew, snipe and little egrets Bouldnor Cliffs CA Wooden causeway at Newtown CA feed on a diet of insects, worms and crustaceans. The Hamstead Heritage Coast is situated on the north ɀ west of the Isle of Wight running from Thorness near A home to 95 different species, suggests that life ɀ The salt marsh at Newtown is a valuable habitat Cowes to Bouldnor near Yarmouth. A tranquil and in the mud of Newtown Harbour is relatively that supports a wide range of wildlife and is also a secretive coastline with inlets, estuaries and creeks; unaffected by human activities. superb natural resource for learning. wooded hinterland and gently sloping soft cliffs, this ɀ Some of the woodland is ancient and the woods beautiful area offers a haven for wildlife including red contain a huge biodiversity with many nationally squirrels and migratory birds. The ancient town of rare species such as red squirrels. Newtown and its National Nature Reserve also fall within this area. -

Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2014 In this issue: One Summer Hornsea Mere Roman Signal Stations on the Yorkshire Coast The Curious Legend of Tom Bell and his Cave at Hardcastle Crags, Near Halifax Jervaulx Abbey This wooden chainsaw sculpture of a monk is by Andris Bergs. It was comissioned by the owners of Jervaulx Abbey to welcome visitors to the Abbey. Jervaulx was a Cistercian Abbey and the medieval monks wore habits, generally in a greyish-white, and sometimes brown and were referred to as the “White Monks” The sculptured monk is wearing a habit with the hood covering the head with a scapula. A scapula was a garment consisting of a long wide piece of woollen cloth worn over the shoulders with an opening for the head Some monks would also wear a cross on a chain around their necks Photo by Brian Wade The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014 Left: Kirkstall Abbey, Leeds in autumn, Photo by Brian Wade Cover: Hornsea Mere, Photo by Alison Hartley Editorial elcome to the autumn issue of The Yorkshire Journal. Before we W highlight the articles in this issue we would like to inform our readers that all our copies of Yorkshire Journal published by Smith Settle from 1993 to 2003 and then by Dalesman, up to winter issue 2004, have all been passed on to The Saltaire Bookshop, 1 Myrtle Place, Shipley, West Yorkshire BD18 4NB where they can be purchased. We no longer hold copies of these Journals. David Reynolds starts us off with the Yorkshire Television drama series ‘One Summer’ by Willy Russell.