This American Life Pitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Anarchism and the British Warfare State: the Prosecution of the War Commentary Anarchists, 1945*

IRSH 60 (2015), pp. 257–284 doi:10.1017/S0020859015000188 © 2015 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Anarchism and the British Warfare State: The Prosecution of the War Commentary Anarchists, 1945* C ARISSA H ONEYWELL Department of Psychology, Sociology and Politics, Sheffield Hallam University Heart of the Campus Building, Collegiate Crescent, Collegiate Campus, Sheffield S10 2BQ, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The arrest and prosecution in 1945 of a small group of London anarchists associated with the radical anti-militarist and anti-war publication War Commentary at first appears to be a surprising and anomalous set of events, given that this group was hitherto considered to be too marginal and lacking in influence to raise official concern. This article argues that in the closing months of World War II the British government decided to suppress War Commentary because officials feared that its polemic might foment political turmoil and thwart postwar policy agendas as military personnel began to demobilize and reassert their civilian identities. For a short period of time, in an international context of “demobilization crisis”, anarchist anti-militarist polemic became a focus of both state fears of unrest and a public sphere fearing ongoing military regulation of public affairs. Analysing the positions taken by the anarchists and government in the course of the events leading to the prosecution of the editors of War Commentary, the article will draw on “warfare- state” revisions to the traditional “welfare-state” historiography of the period for a more comprehensive view of the context of these events. At the beginning of 1945, shortly before the war ended, a small group of London anarchists associated with the radical anti-militarist and anti-war publication War Commentary1 were arrested and prosecuted. -

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in the Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: a Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in The Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: A Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G. Crowther and P.M.S. Blackett Ralph John Desmarais A Dissertation Submitted In Fulfilment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Imperial College London Centre For The History Of Science, Technology And Medicine 2 Abstract This dissertation proposes a revised understanding of the place of science in British literary and political culture during the early atomic era. It builds on recent scholarship that discards the cultural pessimism and alleged ‘two-cultures’ dichotomy which underlay earlier histories. Countering influential narratives centred on a beleaguered radical scientific Left in decline, this account instead recovers an early postwar Britain whose intellectual milieu was politically heterogeneous and culturally vibrant. It argues for different and unrecognised currents of science and society that informed the debates of the atomic age, most of which remain unknown to historians. Following a contextual overview of British scientific intellectuals active in mid-century, this dissertation then considers four individuals and episodes in greater detail. The first shows how science and scientific intellectuals were intimately bound up with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four (1949). Contrary to interpretations portraying Orwell as hostile to science, Orwell in fact came to side with the views of the scientific rig h t through his active wartime interest in scientists’ doctrinal disputes; this interest, in turn, contributed to his depiction of Ingsoc, the novel’s central fictional ideology. Jacob Bronowski’s remarkable transition from pre-war academic mathematician and Modernist poet to a leading postwar BBC media don is then traced. -

Anarchism, Communism and the New Left the Critical Legacy Of

Orwell as Public Intellectual: Anarchism, Communism and the New Left The critical legacy of George Orwell as a public intellectual is a matter of on-going debate by a variety of political factions. Here I seek to offer a sympathetic, but also critical account of Orwell as a complex socialist intellectual who offered an on-going commentary on the times in which he lived and whose legacy continues to bare a considerable amount of historical weight in the present (Taylor 2004). Despite Orwell’s commitment to liberalism, freedom and socialism he remains a deeply divisive figure for those with socialist sympathies. Here I seek to explore a number of cultural and intellectual controversies that were ignited by members of the New Left and post-war Anarchism. Orwell was an ambivalent and influential figure for many on the New Left for the way he sought to both distance himself from a Marxist and communist tradition while simultaneously engaging with individualistic and dissenting currents. Orwell also remains significant for the way in which his writing can be connected to an English libertarian tradition and more mainstream versions of liberalism (Mill 1974, Hobhouse 1964). As E.P. Thompson (1979) argues the English left-libertarian tradition can be traced back to the Levellers, Diggers and the Chartists. Here Thompson (1979:21) makes a crucial distinction between a bourgeois individual rights set of arguments (mainstream liberalism) and one more concerned with the collective practice of the community and attempts to deepen egalitarian and democratic sentiments through campaigns from below. Despite the deceptive simplicity of Orwell’s writing I want to argue that both of these intellectual strains find expression within his life and writing. -

George Orwell on Politics and War John Stone*

Review of International Studies, Vol. 43, part 2, pp. 221–239. doi:10.1017/S026021051600036X © British International Studies Association 2016 First published online 11 November 2016 George Orwell on politics and war . John Stone* Senior Lecturer in War Studies, King’s College London Abstract George Orwell is not generally remembered for his views on strategy. Nevertheless a careful reading of his written work reveals a coherent appreciation of war’s strategic dimension. For Orwell, war is a necessary adjunct to politics, and the utility of strategic action should be based on rational con- fi fi https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms siderations of cost and bene t. He rejected paci sm and self-imposed restraints on warfare on the basis that such positions proceeded from unexamined emotional commitments, and were neither instrumentally nor morally sound. He also maintained that the enemy’s political values are an essential input into effective strategic calculations. On this latter basis he criticised the strategic prescriptions of H. G. Wells and B. H. Liddell Hart for limited war with Nazi Germany. Keywords Owell; Strategy; War; Politics George Orwell is probably best known today for his political satire Nineteen Eighty-Four.Itisin many respects his crowning achievement in so far as his writings on totalitarianism are concerned. And yet it was preceded by various other novels and documentaries, along with a great many essays, that continue to repay careful reading. Indeed had he never written his final book, his position as one fi , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at of the nest essayists of the twentieth century would nevertheless have been secure. -

![Love and Sex[Edit]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8127/love-and-sex-edit-6778127.webp)

Love and Sex[Edit]

Love and sex[edit] See also: Free love Oz number 28, also known as the "Schoolkids issue of OZ", which was the main cause of a 1971 high-profile obscenity case in the United Kingdom. Oz was a UK underground publication with a general hippie / counter-cultural point of view. The common stereotype on the issues of love and sex had it that the hippies were "promiscuous, having wild sex orgies, seducing innocent teenagers and every manner of sexual perversion."[97] The hippie movement appeared concurrently in the midst of a rising Sexual Revolution, in which many views of the status quo on this subject were being challenged. The clinical study Human Sexual Response was published by Masters and Johnson in 1966, and the topic suddenly became more commonplace in America. The 1969 book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask) by Dr. David Reuben was a more popular attempt at answering the public's curiosity regarding such matters. Then in 1972 appeared The Joy of Sex by Alex Comfort, reflecting an even more candid perception of love-making. By this time, the recreational or 'fun' aspects of sexual behavior were being discussed more openly than ever before, and this more 'enlightened' outlook resulted not just from the publication of such new books as these, but from a more pervasive Sexual Revolution that had already been well underway for some time.[97] The hippies inherited various countercultural views and practices regarding sex and love from the Beat Generation; "their writings influenced the hippies to open up when it came to sex, and to experiment without guilt or jealousy."[98] One popular hippie slogan that appeared was "If it feels good, do it!"[97] which for many "meant you were free to love whomever you pleased, whenever you pleased, however you pleased. -

Interview with Michael Randle

Interview no. 27 Michael Randle interview transcript 17th June 2015 After Hiroshima project Interviewee: Michael Randle, DOB 21.12.1933 Interviewer: Ruth Dewa (0:00) MR: Yes, I er it is RD: So this is Ruth Dewa recording on the 17th of June and I’m interviewing Michael Randle. Would you mind spelling your name and telling me your date of birth? MR: Right, its Michael, normal spelling M-I-C-H-A-E-L and Randle is R-A-N-D-L-E. I was born on the 21st December 1933 erm what else we-we-well in Bradford [laugh]. RD: Lovely and this is for the After Hiroshima project at London Bubble. So could you just start by er telling me what you were doing towards the end of the Second World War? MR: Well I was er still a child at the end of the Second World War and I had lived the previous five years with er my aunt and grandparents in Dublin. So I was – I was in London at the beginning of the Blitz but then, the oldest of what were eventually nine children erm was sent to-to live in Ireland with er in Dublin and I went to a-a convent school in Dublin. Erm so we came back just after the end of the war and then we lived in Surrey er Cheam that Cheam Sutton, that sort of area. RD: And what was your experience of Ireland towards the end of the war? Was it kind of - someone else that I’ve interviewed said they kinda felt very detached from it and that they were rather untouched there. -

New Hippies.P65

Hippies From A to Z Their Sex, Drugs, Music and Impact on Society from the Sixties to the Present. by Skip Stone A to Z Page 1 Hippies From A to Z Their Sex, Drugs, Music and Impact on Society from the Sixties to the Present. Copyright 1999, 2008 by Skip Stone All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form. Published by Hip, Inc. PO Box 2993, Silver City, New Mexico 88062 To order this book online, view our catalogue or purchase an electronic version visit our website at: http://hippy.com Written by Skip Stone Editing, Page Layout and Book Design by Martin Trip ISBN Number: First Edition: November 1999 Digital Edition: January 2008 Digital Edition created by Chris Thompson Page 2 Hippies Table of Contents Deadication ..................................................................... 5 Preface ............................................................................. 7 Forward ........................................................................... 9 Introduction................................................................... 11 Part I The Way of the Hippy ..................................................13 Sex, Love & Hippies ...................................................... ? Hippies and Drugs .......................................................... ? Hippy Fashions & Lifestyles ......................................... ? Hippy Activism ................................................................ ? The Astrology of the Hippy Movement.......................... -

Reinventing Social-Movement Repertoires: the ‘Operation Gandhi’ Experiment

Reinventing Social-Movement Repertoires: The ‘Operation Gandhi’ Experiment Anti-capitalists in Prague, Genoa and Melbourne proclaim the need to organise a Seattle- style protest, and contest the global dominance of transnational corporations; Australian students concerned with racial injustice join together in a Freedom Ride that faithfully mirrors the American example; socialists around the world form a new sort of ‘Communist’ party in the wake of the inspirational revolution of the Russian Bolsheviks; Gandhi’s non-violent acts spawn a host of sincere imitators in the U.S., U.K., and Africa. Four historical examples of the diffusion of collective action. How do such political translations occur? How do contentious political performances move from one national context to another? This problem has traditionally been elided within social movement scholarship. The most influential studies have focused on the development of a modular, transposable repertoire of collective action,1 and have largely treated diffusion as the automatic reflection of “appropriateness” and political utility,2 or else, as has been noted elsewhere, as the product of direct experience on the part of activists,3 or structural similarity between the ‘transmitter’ and ‘adopter’ of the new performances.4 However, this rather superficial view has recently been undermined by a growing interest in globalisation, and by a cluster of theoretical and historical work. An emergent consensus now suggests that diffusion rests upon a sustained labour of cultural, intellectual, and practical translation.5 Similarity between ‘initiator’ and ‘receiver’ must be constructed or framed, and identification fostered.6 Brokers ease the process of transmission.7 The precise dynamics of diffusion will take on a different form, depending upon the relative activity of the transmitter and the adopter.8 The repertoire is not simply 1 The classic example is Charles Tilly, Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758-1834, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. -

The Good Life: Weakness in the Survival Years a Dissertation

The Good Life: Weakness in the Survival Years A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Robert St. Lawrence IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Jani Scandura and Maria Damon December 2018 Copyright Robert St. Lawrence, 2018 i Acknowledgments This dissertation project would never have been completed without the continued support and engagement of my advisors, Maria Damon and Jani Scandura, and the other members of my dissertation committee, Tony Brown and Christophe Wall-Romana. It would have been equally incomplete without my colleagues, including Mike Rowe, Wes Burdine, Andrew Marzoni, Val Bherer, Stephen McCulloch, Hyeryung Hwang, Annemarie Lawless, and the many others whose conversation and advise helped shape my work since 2009. I have drawn great inspiration from those who have taken the time to provide mentor- and friendship along the way, such as Joe Hughes and Charles Legere. And my colleagues in the state of Washington have been both patient and generous as I worked toward completing this project. Of course, I would never have embarked down this path without the support and love of my partner, Carrie Graf. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Alma Lyell Graf St. Lawrence. iii Abstract In a 1948 questionnaire, the editors of the Partisan Review felt safe in asserting that “it is the general opinion that, unlike the twenties, this is not a period of experiment in language and form.” The socially aware writers of 1948 felt the impasse of their situation acutely, a suspended sensibility given its clearest expression by John Berryman, who explained that “this has been simply the decade of Survival.” The decade’s self- image for many of its “Leftish” writers was bereft of the creative, life-building activity that had marked the revolutionary realisms of the past decades. -

Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow

Anarchist Seeds beneath the Snow Goodway_00_Prelims.indd i 6/9/06 15:56:26 Goodway_00_Prelims.indd ii 6/9/06 15:56:26 Anarchist Seeds beneath the Snow Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward DAVID GOODWAY LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS Goodway_00_Prelims.indd iii 6/9/06 15:56:26 First published 2006 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2006 David Goodway The right of David Goodway to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 1-84631-025-3 cased ISBN 1-84631-026-1 limp ISBN-13 978-1-84631-025-6 cased ISBN-13 978-1-84631-026-3 limp Typseset in Fournier by Koinonia, Manchester Printed and bound in the European Union by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn Goodway_00_Prelims.indd iv 6/9/06 15:56:26 Contents Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 2 Anarchism and libertarian socialism in Britain: William Morris and the background, 1880–1920 15 3 Edward Carpenter 35 4 Oscar Wilde 62 5 John Cowper Powys I: His life-philosophy and individualist anarchism 93 6 The Spanish Revolution and Civil War – and the case of George Orwell 123 7 John Cowper Powys II: The impact of Emma Goldman and Spain 149 8 Herbert Read 175 9 War and pacifi sm 202 10 Aldous Huxley 212 11 Alex Comfort 238 12 Nuclear disarmament, the New Left – and the case of E.P. -

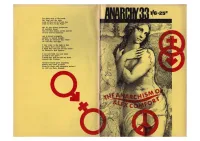

Anarchy No. 33

—— Contents of No. 33 November 1963 ANARCHY 33 (Vol 3 No II) November 1 963 329 The Anarchism of Alex Comfort /<?/*« Ellerby 329 Sex, Kicks and Comfort Charles Radcliffe 340 Alex Comfort's Art and Scope Harold Drasdo 345 A Comfort Bibliography 357 A Disappointed Revolutionary Sid Parker 359 Cover by Rufus Segar Drawing on p. 329 by Frank Benier <0o Poem "Maturity" by Alex Comfort from Haste to the Wedding (Eyre and Spottiswoode 1962) The ANARCHISM of Other issues of ANARCHY 27. Talking about youth. 28. The future of anarchism. COMFORT 1. Sex-and-Violence; Galbraith; ALEX (out of print) 29. The Spies for Peace Story the New Wave, Education, 30. The community workshop. 31. Self-organising systems; 2. Workers' Control. beatniks; the state; practicability. 3. What does anarchism mean today?; 32. Crime. Africa; the Long Revolution; 4. De-institutionalisation; Conflicting Universities strains in anarchism. and Colleges ANARCHY can be obtained in term- 5. 1936: the Spanish Revolution. time from: (out of print) Oxford: Felix de Mendelssohn, J us i ai 1 1 r rut- WAR; two young writers on either side of the Atlantic 6. Anarchy and the Cinema. Oriel College. published collections of their wartime essays. Their books had a (out of print) Cambridge: Nicholas Bohm similar character, were of social as well as literary 7. Adventure Playgrounds. tone and both St. John's College. criticism, they even similar titles: Paul Goodman's was called (out of print) Birmingham: Anarchist Group. and had 8. Anarchists and Fabians; Action Sussex: Paul Littlewood, Art and Social Nature, Alex Comfort's was called Art and Social Anthropology; Eroding Capitalism; Students' Union.