The Desire and Struggle for Recognition Bjorn Wee Gomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+\Shu Dqg Plvxqghuvwdqglqj Lq Lqwhudfwlrqdo

1 +\SHUDQGPLVXQGHUVWDQGLQJLQLQWHUDFWLRQDOKXPRU Geert Brône University of Leuven Department of Linguistics Research Unit &UHDWLYLW\+XPRUDQG,PDJHU\LQ/DQJXDJH (CHIL) E-mail address: [email protected] $ ¢¡¤£¦¥¢§©¨ £ This paper explores two related types of interactional humor. The two phenomena under scrutiny, K\SHUXQGHUVWDQGLQJ and PLVXQGHUVWDQGLQJ, categorize as responsive conversational turns as they connect to a previously made utterance. Whereas hyper-understanding revolves around a speaker’s ability to exploit potential weak spots in a previous speaker’s utterance by playfully echoing that utterance while simultaneously reversing the initially intended interpretation, misunderstanding involves a genuine misinterpretation of a previous utterance by a character in the fictional world. Both cases, however, hinge on the differentiation of viewpoints, yielding a layered discourse representation. A corpus study based on the British television series %ODFNDGGHU reveals which pivot elements can serve as a trigger for hyper- and misunderstanding. Common to all instances, it is argued, is a mechanism ofILJXUHJURXQG UHYHUVDO. Key words: interactional humor, hyper-understanding, misunderstanding, layering, mental spaces, figure-ground reversal 2 ,QWURGXFWLRQ Recent studies in pragmatics (see e.g. Attardo 2003) have shown a renewed interest in humor as a valuable topic of interdisciplinary research. More specifically, these studies have extended the traditional focus of humor research on jokes to include longer narrative texts (Attardo 2001a, Triezenberg 2004) and conversational data (Boxer and Cortés-Conde 1997, Hay 2001, Kotthoff 2003, Norrick 2003, Antonopoulou and Sifianou 2003, Archakis and Tsakona 2005). New data from conversation analysis, text linguistics and discourse psychology present significant challenges to linguistic humor theories like the General Theory of Verbal Humor (Attardo 1994, 2001a), and call for (sometimes major) revisions. -

Li4j'lsl!=I 2 Leeds Student Ma Aj Rnutidoo ®~1 the Bulk of Landlords .Trc \.\Ith News Ump,.'11

THE REVOLT T F TH HT --FULL STORY PAGE NINE -----li4J'lSl!=I 2 www.leedsstudentorg.uk Leeds Student ma aJ rnutIDoo ®~1 the bulk of landlords .trc \.\ith News Ump,.'11. 20 per ce n1 uren ·1 and LIBERAL Democnil MP in the ..crabbl c 10 find holbm,1: S0%of Simon llu~ht-s has helped in LS6. .., ,uden~ forgc1 11t.11 kick-start a new student the) have nghl\." students have hou."iing crlCMJdc. Jame:; Blake, pre,;idenJ ot taken drugs lhc ·m1111 campaign . Ll'l I\ Lib Dem pan), said but they want wluch I\ be ing c;pearheadc<l h) ·-rm so plc:t5cd thut Simon the:" J~ll:, LT111vcr-.U) L1h rkm Hughe!. could launt:h th 1.:. stricter laws part). •~ .ummg In _maJ..i: c:1mpa1~.n· i1 ,hows YrC an• pt.-<1ple more aware. ol 1he1r ',C.."OOU!, nglu .. :L, IC/M Ii t.. Hu~hC!-i. \\ ho was narmwl} pages TennnL!- can dl!m.Jnd 1h i 11 w, hct11cn by Charles Kenned)- in like ',llltllu: de1cc1or... gu~ a le..ader.; lup contest. ~ id: {ee:-. for appl i,mcc\ and '"StuJcn1 .-. olten fc.el 1hat Uni of Leeds found wanting by aik-qualc 101.;b. filling,. becau~ they mm,e around 11 \ government watchdogs Greg Mulholland. a t.-01111 not '-"Onh \. Otmg. We wam 10 tell lhem lh:it ii I\, nnd lhat pages 6 · 7 cillur for l.ttJs ~fonh \\'1....,1 who i.. .il!.O baekm!! the wc · n: n:lc\'an1 ...chcme. ,,;md: ··1t\ the ... mall "If ~IUdent.,;. -

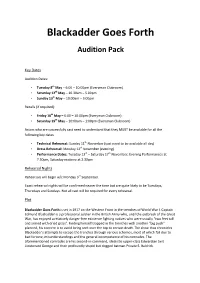

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

MY BOOKY WOOK a Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand

MY BOOKY WOOK A Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand For my mum, the most important woman in my life, this book is dedicated to you. Now for God’s sake don’t read it. “The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between po liti cal parties either, but through every human heart” Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago “Mary: Tell me, Edmund: Do you have someone special in your life? Edmund: Well, yes, as a matter of fact, I do. Mary: Who? Edmund: Me. Mary: No, I mean someone you love, cherish and want to keep safe from all the horror and the hurt. Edmund: Erm . Still me, really” Richard Curtis and Ben Elton, Blackadder Goes Forth Contents iii Part I 1 April Fool 3 2 Umbilical Noose 16 3 Shame Innit? 27 4 Fledgling Hospice 38 5 “Diddle- Di- Diddle- Di” 50 6 How Christmas Should Feel 57 7 One McAvennie 65 8 I’ve Got a Bone to Pick with You 72 9 Teacher’s Whiskey 8186 94 10 “Boobaloo” 11 Say Hello to the Bad Guy Part II 12 The Eternal Dilemma 105111 13 Body Mist Photographic Insert I 14 Ying Yang 122 131 138146 15 Click, Clack, Click, Clack 16 “Wop Out a Bit of Acting” 17 Th e Stranger v Author’s Note Epigraph vii Contents 18 Is This a Cash Card I See before Me? 159 19 “Do You Want a Drama?” 166 Part III 20 Dagenham Is Not Damascus 179 21 Don’t Die of Ignorance 189 22 Firing Minors 201 Photographic Insert II 23 Down Among the Have-Nots 216 24 First-Class Twit 224 25 Let’s Not Tell Our Mums 239 26 You’re a Diamond 261 27 Call Me Ishmael. -

The Teacher & Student Notes This Lesson Plan

Student’s page 1 Warm-up Ask and answer these questions. Then, report back to the class with any answers or information. Losing things! • When was the last time you lost something? What was it? • Have you misplaced anything lately? What was it? Did you ever find it again? • Have you ever accused someone of having taken something of yours? What was it? • Why did you accuse them? What happened in the end? • Has anyone ever accused you of having taken something of theirs? What was it? Why did they accuse you? What happened in the end? • How careful are you about putting away your things? How easy is it to find something if you need it? What are your top tips for not losing things? • Have you ever lost any socks? Have any of your socks ever gone missing mysteriously? • Where do you think all the missing socks go? 2 First viewing You’re going to watch a clip from the British comedy series Blackadder the Third, which aired during the 1980s. The series is set in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period known as the Regency. For much of this time, King George III was incapacitated due to poor mental health, and his son George, the Prince of Wales, acted as regent, becoming known as “the Prince Regent". The TV series features Prince George and his fictional butler, Edmund Blackadder. Watch the clip once. How would you describe the relationship between the butler and the prince? Who seems to be in charge? 3 Second viewing Watch the video again. -

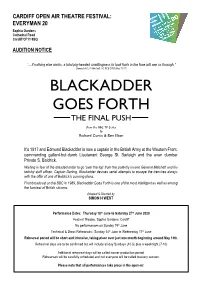

Blackadder Goes Forth the Final Push

CARDIFF OPEN AIR THEATRE FESTIVAL: EVERYMAN 20 Sophia Gardens Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9SQ AUDITION NOTICE “... if nothing else works, a total pig-headed unwillingness to look facts in the face will see us through.” General A.C.H. Melchett, VC KCB DSO (May 1917) BLACKADDER GOES FORTH THE FINAL PUSH from the BBC TV Series by Richard Curtis & Ben Elton It's 1917 and Edmund Blackadder is now a captain in the British Army at the Western Front, commanding gallant-but-dumb Lieutenant George St. Barleigh and the even dumber Private S. Baldrick. Waiting in fear of the dreaded order to go 'over the top' from the patently insane General Melchett and his twitchy staff officer, Captain Darling, Blackadder devises serial attempts to escape the trenches always with the offer of one of Baldrick's cunning plans. First broadcast on the BBC in 1989, Blackadder Goes Forth is one of the most intelligent as well as among the funniest of British sitcoms. Adapted & Directed by SIMON H WEST Performance Dates: Thursday 18th June to Saturday 27th June 2020 Festival Theatre, Sophia Gardens, Cardiff No performances on Sunday 19th June Technical & Dress Rehearsals: Sunday 14th June to Wednesday 17th June Rehearsal period will be short and intensive, taking place over just one month beginning around May 14th. Rehearsal days are to be confirmed but will include all day Sundays (10-5) plus a weeknight (7-10) Additional rehearsal days will be called nearer production period. Rehearsals will be carefully scheduled and not everyone will be called to every session. Please note that all performances take place in the open-air. -

Views & Reviews the Highs and Lows of Policy Based Evidence

Why don’t practices encourage patients to VIEWS & REVIEWS enrol on the organ donor register online, asks Des Spence, p 1090 The highs and lows of policy based evidence PERSONAL VIEW David Colquhoun emember George W Bush? For are to offer advice to ministers, “where Leaf him it was simple. If a scientist either the Council consider it expedient storm: told him an inconvenient truth, to do so or they are consulted by the cannabis the messenger was fired, and Minister.” They do not have to wait to be is at the centre of the row over someone more compliant got asked. scientific advice to Rthe job. In every area from global warming Nutt didn’t wait, and he got fired. ministers to the existence of weapons of mass Twitter was ablaze, quickly followed by the destruction he chose to base policy on mainstream media. reason for fantasy and wishful thinking. It seems that This furore arose simply because Nutt including the UK home secretary, Alan Johnson, has said that cannabis was less dangerous than ecstasy with something in common with Bush. When tobacco and alcohol (true) and that more heroin in class A was to make the Advisory Council on the Misuse of people were killed and brain damaged people think that ecstasy was as Drugs (ACMD) said something he didn’t from riding accidents than from ecstasy dangerous as heroin (not true, but like, its chairman, David Nutt, got fired (also true). His Eve Saville lecture, for the precautionary). But it is just as likely (BMJ 2009;339:b4563). -

Thursday, March 4, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20 ‘Gutted’

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 ‘GUTTED’ SURF LIFESAVING NATIONALS CANCELLED PAGE 3 SLOW LANE WAITING WEEKS TO SIT DRIVER LICENCE TEST PAGE 4 RECONNECTING: East Coast actress Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne plays the role of an adult Makareta in the New Zealand movie Cousins, which had its Gisborne premiere last night. In this scene, Makareta receives a moko kauae. Themes of colonisation, separation and cultural identity are explored in this drama about three young cousins whose lives take decidedly different paths but are reconnected many years later through a twist of fate. Te Araroa-raised Ngatai-Melbourne says she drew on her upbringing in her role and came to appreciate the importance of Maori storytelling while filming. She hope all those who see the movie take something from it. ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT STORY ON PAGE 2 PICTURES SUPPLIED PAGES 23 - 26 ‘EVERY DOSE COUNTS’ On track to complete 300 vaccinations this week “TRAILBLAZING” efforts to vaccinate “At each stage there were enthusiastic, sequencing developed by the Ministry of “I also want to pay tribute to our the first 300 eligible Tairawhiti residents knowledgeable people working as a Health. trailblazing border workers and their against Covid-19 have reached the concerted team to get the job done. Mr Green said there had been much households. You have shown us all how to halfway mark. “This was the first day of vaccinating feedback on how appreciative people step up and put the safety of your families Tairawhiti vaccinators are on target 38,000 Tairawhiti people in about nine were to get vaccinated, and how “friendly, and the wider community up front. -

In the Night Garden

Highlights | August 2011 For further information and images, please contact: UK: Nick Myles Editorial Coordinator BBC Worldwide Channels E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +44 20 8433 2000 Produced by EBS New Media www.ebs.tv + 44 1462 895 999 Editorial Manager: Paul Talbot [email protected] August 2011 Highlights Britain’s Funniest Comedian BBC Entertainment presents a month of top comedy with four of Britain’s funniest comedians. John Cleese, Rowan Atkinson, Ricky Gervais and Stephen Fry are featured in their finest shows, and viewers are invited to vote for their favourite on the BBC Entertainment website. John Cleese From Sunday 7 August from 18:00 Kicking off the proceedings, the legendary John Cleese stars in classic 70s sitcom Fawlty Towers. Cleese gives an iconically hysterical performance as Basil Fawlty, the much put-upon hotel manager whose life is plagued by dead guests, hotel inspectors and riff-raff, not to mention hapless waiter Manuel’s peculiar attachment to a certain rodent. Rowan Atkinson From Sunday 14 August at 18:00 The Blackadder series sees the inimitable Rowan Atkinson starring as four different incarnations of Edmund Blackadder. In The Black Adder he is Edmund, Duke of Edinburgh, haunted by his uncle Richard III who he accidentally killed. In Blackadder II, Lord Edmund swaggers back with a big head and a small beard in search of grace and favour from stark raving mad Queen Elizabeth I. In Blackadder the Third, Edmund has been reduced in status and is serving as butler to the Prince Regent (Hugh Laurie), and in Blackadder Goes Forth we find him doing everything he can to avoid a futile death in the trenches of the First World War. -

UNIVERSITY of VAASA Faculty of Philosophy English Studies Erika Bertell Translation of Wordplay and Allusions the Finnish Subti

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Osuva UNIVERSITY OF VAASA Faculty of Philosophy English Studies Erika Bertell Translation of Wordplay and Allusions The Finnish Subtitling of Blackadder Master‘s Thesis Vaasa 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 4 1 INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 Material 12 1.2 Method 18 1.3 Blackadder – The Whole Damn Dynasty 22 1.3.1 Situation Comedies 24 1.3.2 British Humour in Blackadder 25 1.4 Subtitling in Finland 31 1.4.1 (In)visibility of Translators 32 1.4.2 BTI International and Audiovisual Translators 33 1.4.3 Audiovisual Translators United 34 2 VERBAL HUMOUR 36 2.1 Humour Theories 37 2.2 Wordplay 41 2.3 Allusions 46 3 SUBTITLING 51 3.1 General Information 52 3.1.1 DVD Translation 54 3.2 Limitations and Constraints 55 3.2.1 Benefits of Subtitling 58 3.3 Subtitling and Pictorial Links 60 4 TRANSLATION STRATEGIES FOR VERBAL HUMOUR 66 4.1 Views on the (Un)translatability of Verbal Humour 67 4.2 Holmes's Retentive and Re-creative Strategies 69 4.3 Translation Techniques for Wordplay 71 2 5 TRANSLATION OF VERBAL HUMOUR IN BLACKADDER 73 5.1 Findings 74 5.2 Retention of Verbal Humour 78 5.2.1 Examples in Wordplay 80 5.2.2 Examples in Allusions 81 5.3 Re-creation of Verbal Humour 83 5.3.1 Examples in Wordplay 84 5.3.2 Examples in Allusions 87 5.4 Omission and Addition of Verbal Humour 88 5.4.1 Examples in Wordplay 89 5.4.2 Examples in Allusions 91 6 CONCLUSIONS 94 WORKS CITED 98 4 UNIVERSITY OF VAASA Faculty of Philosophy Discipline: English Studies Author: Erika Bertell Master’s Thesis: Translation of Wordplay and Allusions The Finnish Subtitling of Blackadder Degree: Master of Arts Date: 2014 Supervisor: Kristiina Abdallah ABSTRACT Ulkomaisten, tekstitettyjen komediasarjojen osuus Suomen televisiotarjonnassa kasvaa alati, ja markkinoilla on myös enemmän kuin koskaan DVD-käännöksiä. -

Blackadder 2 Master Script Updated

“Head” Play script “Head” (Setting: In the house of Edmund Blackadder. Edmund and Baldrick are counting beans…) EDMUND: Right Baldrick, let's try again shall we? This is called adding. If I have two beans, and then I add two more beans, what do I have? BALDRICK: Some beans. EDMUND: Yes...and no. Let's try again shall we? I have two beans, then I add two more beans. What does that make? BALDRICK: A very small casserole. EDMUND: Baldrick, the ape creatures of the Indus have mastered this. Now try again. One, two, three, four. So how many are there? BALDRICK: Three EDMUND: What? BALDRICK: And that one. EDMUND: Three and that one. So if I add that one to the three what will I have? BALDRICK: Oh! Some beans. EDMUND: Yes. To you Baldrick, the renaissance was just something that happened to other people wasn't it? (Percy enters, wearing an enormous ruff.) PERCY: Edmund, Edmund, come quickly the queen wants to see you. EDMUND: What…? PERCY: I said "Edmund, Edmund, come quickly the queen wants to see-" EDMUND: Please let me finish. What, are you wearing round your neck? PERCY: Ah! It's my new ruff! EDMUND: You look like a bird who's swallowed a plate! PERCY: It's the latest fashion actually and as a matter of fact it makes me look rather sexy! EDMUND: To another plate swallowing bird perhaps. If it was blind and hadn't had it in months. MKTOC. The Workshop, Clickers Yard, Olney, Bucks. MK46 5DX 2 Tel: 01234 241357. -

Intelligence Corps Meadows? 16

N il Desperandum Published for Haywards Heath & District Probus Club ISSUE 8 November 2020 Isolated but not alone Picture Credit: "Inverse proportions" by GB_Teddy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Index: 10. What does Pedagogy mean? 1. Oh, Dear God (or) Oh Dear, God 10. Some Jigsaws are difficult 1. Humour 11. What is a vomitirium? 1. Ants aren’t going to be hungry 11. What’s a ‘Pathogen’? 2. The True Story of the American Frontier's First 11. Social Distancing in the Animal World Gunfighter 12. Mennonite Trickster and Dramatic Hero 3. Rat empathy is surprisingly like human empathy 13. Is this the best speech ever? 3. Step up your walking game 14. How to Tell a Story 4. What has happened to all our English Wild Flower 15. Intelligence Corps Meadows? 16. A big black hole: It’s very hungry 4. Warfare History Network 16. Black History Month: Postboxes painted to honour 5. Pause for thought black Britons 5. Snappy one-liners (keep a straight face) 17. Lost Love 6. A young monk arrives at the Monastery… 17. Libel vs. Slander: What’s the difference? 7. The year 1985 18. Donald Trump 8. Random excerpts from Blackadder 19. 5 key dates in the Battle of Britain 9. ‘Pragmatic’ versus ‘Dogmatic’: What’s the Difference? 20. Has Social Distancing gone mad? 9. Pragmatic Quotations 20. Airbus and Commercial Hydrogen Planes 10. What happened next? 20. Dad’s Army 10. Wild Bison in Kent 21. Finish with a giggle Nil Desperandum ISSUE 8 November 2020 Isolated but not alone Oh, Dear God (or) Oh Dear, God It doesn’t seem right, that with all of your might, You haven’t observed yet, in man’s efforts to know you, we created thousands* of faiths, each claiming to be true, each one says and believes they are the closest to you.