Anachronism and the Limits of Laughing at the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leicester Beer Festival 2015

Leicester Beer Festival 2015 www.leicestercamra.org.uk Facebook/leicestercamra @LeicesterCAMRA 11 - 14 MARCH CHAROTAR PATIDAR SAMAJ, BAY STREET, LEICESTER LEICESTER BEER FESTIVAL 2015 1 TIGER BEST BITTER www.everards.co.uk @EverardsTiger facebook.com/everards LEICESTER BEER FESTIVAL 2015 2 Southwell Folk Fest A5 ad Portrait.indd 1 16/05/2014 16:25 Chairman’s Welcome At last, it’s that time of the year again and I would like to welcome you to the Leicester CAMRA Beer Festival 2015. This is the sixteenth since our re-launch in 1999 following a ten-year absence. We are delighted to be back at the Charotar Patidar Samaj for the fifteenth time. As always we are showcasing the brewing expertise of our Leicestershire and Rutland breweries on our LocAle bars, we also feature a selection of breweries within 25 miles as the crow flies from the festival site giving an amazing 40 breweries within the area to choose from. This year we have divided the servery up into six distinct bars and colour-coded them (see p 15 for details). We have numbered the beers to make it easier to remember what to order at the bar. Our festival is one of many that play a major role not just as fund raising, but also to keep people informed about CAMRA’s work and the vast range of beers that are now available to the consumer. This continuous background work nationwide has doubtless helped change attitudes towards real ale. Our theme this year is XV, a full explanation of which appears in the article on page 9. -

Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/02 Dorothea Flothow 5 Unheroic and Yet Charming – Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays It has been claimed repeatedly that unlike previ- MacDonald’s Not About Heroes (1982) show ous times, ours is a post-heroic age (Immer and the impossibility of heroism in modern warfare. van Marwyck 11). Thus, we also fi nd it diffi cult In recent years, a series of bio-dramas featuring to revere the heroes and heroines of the past. artists, amongst them Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus In deed, when examining historical television se- (1979) and Sebastian Barry’s Andersen’s En- ries, such as Blackadder, it is obvious how the glish (2010), have cut their “artist-hero” (Huber champions of English imperial history are lam- and Middeke 134) down to size by emphasizing pooned and “debunked” – in Blackadder II, Eliz- the clash between personal action and high- abeth I is depicted as “Queenie”, an ill-tempered, mind ed artistic idealism. selfi sh “spoiled child” (Latham 217); her immor- tal “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” becomes The debunking of great historical fi gures in re- part of a drunken evening with her favourites cent drama is often interpreted as resulting par- (Epi sode 5, “Beer”). In Blackadder the Third, ticularly from a postmodern infl uence.3 Thus, as Horatio Nelson’s most famous words, “England Martin Middeke explains: “Postmodernism sets expects that every man will do his duty”, are triv- out to challenge the occidental idea of enlighten- ialized to “England knows Lady Hamilton is a ment and, especially, the cognitive and episte- virgin” (Episode 2, “Ink and Incapability”). -

+\Shu Dqg Plvxqghuvwdqglqj Lq Lqwhudfwlrqdo

1 +\SHUDQGPLVXQGHUVWDQGLQJLQLQWHUDFWLRQDOKXPRU Geert Brône University of Leuven Department of Linguistics Research Unit &UHDWLYLW\+XPRUDQG,PDJHU\LQ/DQJXDJH (CHIL) E-mail address: [email protected] $ ¢¡¤£¦¥¢§©¨ £ This paper explores two related types of interactional humor. The two phenomena under scrutiny, K\SHUXQGHUVWDQGLQJ and PLVXQGHUVWDQGLQJ, categorize as responsive conversational turns as they connect to a previously made utterance. Whereas hyper-understanding revolves around a speaker’s ability to exploit potential weak spots in a previous speaker’s utterance by playfully echoing that utterance while simultaneously reversing the initially intended interpretation, misunderstanding involves a genuine misinterpretation of a previous utterance by a character in the fictional world. Both cases, however, hinge on the differentiation of viewpoints, yielding a layered discourse representation. A corpus study based on the British television series %ODFNDGGHU reveals which pivot elements can serve as a trigger for hyper- and misunderstanding. Common to all instances, it is argued, is a mechanism ofILJXUHJURXQG UHYHUVDO. Key words: interactional humor, hyper-understanding, misunderstanding, layering, mental spaces, figure-ground reversal 2 ,QWURGXFWLRQ Recent studies in pragmatics (see e.g. Attardo 2003) have shown a renewed interest in humor as a valuable topic of interdisciplinary research. More specifically, these studies have extended the traditional focus of humor research on jokes to include longer narrative texts (Attardo 2001a, Triezenberg 2004) and conversational data (Boxer and Cortés-Conde 1997, Hay 2001, Kotthoff 2003, Norrick 2003, Antonopoulou and Sifianou 2003, Archakis and Tsakona 2005). New data from conversation analysis, text linguistics and discourse psychology present significant challenges to linguistic humor theories like the General Theory of Verbal Humor (Attardo 1994, 2001a), and call for (sometimes major) revisions. -

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25Years of Great Taste

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25years of Great Taste MEMORIES FOR SALE! Be sure to pick up your copy of the limited edition full-color book, The Great Taste of the Midwest: Celebrating 25 Years, while you’re here today. You’ll love reliving each and every year of the festi- val in pictures, stories, stats, and more. Books are available TODAY at the festival souve- nir sales tent, and near the front gate. They will be available online, sometime after the festival, at the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild website, http://mhtg.org. WelcOMe frOM the PresIdent elcome to the Great taste of the midwest! this year we are celebrating our 25th year, making this the second longest running beer festival in the country! in celebration of our silver anniversary, we are releasing the Great taste of the midwest: celebrating 25 Years, a book that chronicles the creation of the festival in 1987W and how it has changed since. the book is available for $25 at the merchandise tent, and will also be available by the front gate both before and after the event. in the forward to the book, Bill rogers, our festival chairman, talks about the parallel growth of the craft beer industry and our festival, which has allowed us to grow to hosting 124 breweries this year, an awesome statistic in that they all come from the midwest. we are also coming close to maxing out the capacity of the real ale tent with around 70 cask-conditioned beers! someone recently asked me if i felt that the event comes off by the seat of our pants, because sometimes during our planning meetings it feels that way. -

Bald and Bold for St. Baldrick's

Wednesday, February 26, 2014 VOLUME 33 / NUMBER 22 www.uicnews.uic.edu facebook.com/uicnews twitter.com/uicnews NEWS UIC youtube.com/uicmedia For the community of the University of Illinois at Chicago Photo: S.K. Vemmer Carly Harte and Andrea Heath check each other’s new look after their heads were shaved in a fundraiser for St. Baldrick’s Foundation Thursday. The roommates drove from Milwaukee to Children’s Hospital University of Illinois for the event, which benefits pediatric cancer research at UIC and elsewhere. More on page 3; watch the video atyoutube.com/uicmedia Bald and bold for St. Baldrick’s INSIDE: Profile / Quotable 2 | Campus News 4 | Calendar 12 | Student Voice 13 | Police 14 | Sports 16 Composer Steve Everett finds the Honoring UIC’s Researchers of Cai O’Connell’s once-in-a-lifetime Women’s basketball gets ready to right notes the Year Olympics assignment break the record More on page 2 More on page 7 More on page 11 More on page 16 2 UIC NEWS I www.uicnews.uic.edu I FEBRUARY 26, 2014 profile Send profile ideas to Gary Wisby,[email protected] Composer Steve Everett hits right notes with technology By Gary Wisby Princeton and a guest composer at Eastman School of Music, Conservatoire National Supérieur de Mu- Epilepsy. sique de Paris, Conservatoire de Musique de Genève The chemical origins of life. in Switzerland, Rotterdam Conservatory of Music A young prostitute who lived in and Utrecht School of the Arts in the Netherlands. New Orleans’ notorious Storyville His compositions have been performed in Paris, 100 years ago. -

Li4j'lsl!=I 2 Leeds Student Ma Aj Rnutidoo ®~1 the Bulk of Landlords .Trc \.\Ith News Ump,.'11

THE REVOLT T F TH HT --FULL STORY PAGE NINE -----li4J'lSl!=I 2 www.leedsstudentorg.uk Leeds Student ma aJ rnutIDoo ®~1 the bulk of landlords .trc \.\ith News Ump,.'11. 20 per ce n1 uren ·1 and LIBERAL Democnil MP in the ..crabbl c 10 find holbm,1: S0%of Simon llu~ht-s has helped in LS6. .., ,uden~ forgc1 11t.11 kick-start a new student the) have nghl\." students have hou."iing crlCMJdc. Jame:; Blake, pre,;idenJ ot taken drugs lhc ·m1111 campaign . Ll'l I\ Lib Dem pan), said but they want wluch I\ be ing c;pearheadc<l h) ·-rm so plc:t5cd thut Simon the:" J~ll:, LT111vcr-.U) L1h rkm Hughe!. could launt:h th 1.:. stricter laws part). •~ .ummg In _maJ..i: c:1mpa1~.n· i1 ,hows YrC an• pt.-<1ple more aware. ol 1he1r ',C.."OOU!, nglu .. :L, IC/M Ii t.. Hu~hC!-i. \\ ho was narmwl} pages TennnL!- can dl!m.Jnd 1h i 11 w, hct11cn by Charles Kenned)- in like ',llltllu: de1cc1or... gu~ a le..ader.; lup contest. ~ id: {ee:-. for appl i,mcc\ and '"StuJcn1 .-. olten fc.el 1hat Uni of Leeds found wanting by aik-qualc 101.;b. filling,. becau~ they mm,e around 11 \ government watchdogs Greg Mulholland. a t.-01111 not '-"Onh \. Otmg. We wam 10 tell lhem lh:it ii I\, nnd lhat pages 6 · 7 cillur for l.ttJs ~fonh \\'1....,1 who i.. .il!.O baekm!! the wc · n: n:lc\'an1 ...chcme. ,,;md: ··1t\ the ... mall "If ~IUdent.,;. -

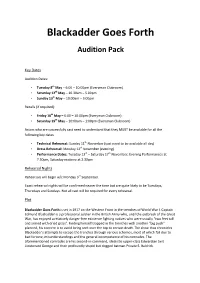

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

Defamatory Humor and Incongruity's Promise

JUST A JOKE: DEFAMATORY HUMOR AND INCONGRUITY’S PROMISE LAURA E. LITTLE* Can’t take a joke, eh? A little levity is good for body, mind, and soul, y’know. Suing over THAT little schoolyard jab? I say you’re either “thin- skinned or a self-important prig . .”1 I. INTRODUCTION At what point does a joke become a legal wrong, justifying resort to defamation law? And at what point must a lawyer tell his or her client to steer clear of humor—or at least keep jokes focused exclusively on public figures, officials, and matters of clear public interest? The challenge of drawing the line between protecting and restricting humor has dogged United States courts for years. And what a difficult line it is to chart! First, the line must navigate a stark value clash: the right of individuals and groups to be free from attack on their property, dignity, and honor versus the right of individuals to free expression. To make matters more complicated—in fact, much more complicated—the line must not only account for, but also respect, the artistry of comedy and its beneficial contributions to society. In regulating defamation, American courts deploy a familiar concept for navigating the line between respecting humor and protecting individual * Copyright 2012 held by Laura E. Little, Professor of Law, Temple University’s Beasley School of Law; B.A. 1979, University of Pennsylvania; J.D. 1985 Temple University School of Law. I am grateful for the excellent research assistance of Theresa Hearn, Alice Ko, and Jacob Nemon, as well as the helpful comments of my colleague Professor Jaya Ramji-Nogales. -

Highlights of UK and Ireland

Highlights of UK and Ireland Tour start & end points Start point: Start in: Pick‐up Location: Pickup Address: Time: London Outside Hotel Novotel at 173‐185 Greenwich High 06:30 hrs Greenwich Station Road, SE10 8JA London London Hotel Lobby, Holiday Inn 85 Bugsby Way, 07:00 hrs Express, Greenwich Greenwich, SE10 0GD London End point: End in: Drop‐off point: Time: Greenwich Train Station 173‐185 Greenwich High 17:00 hrs – 19:30 hrs Road, SE10 8JA London Before the tour starts, we require travellers to check‐in at one of our pre‐selected pickup points Pick‐up points details Highlights of UK and Ireland 1 Option 1: Outside Hotel Novotel at Greenwich Station Our main pick up point is outside Greenwich Train Station. The meeting time is 06:30 hours. Greenwich station serves National Rail services, as well as the DLR (Docklands Light Railway), which is connected with the London Underground (tube) system. Please use Transport for London's Journey Planner to plan your journey. Option 2: Hotel Lobby, Holiday Inn Express, Greenwich This hotel serves as the 2nd meeting point ‐ the coach will pick up outside the hotel at between 07:00 ‐ 07:15 hours (traffic dependent) If you are meeting the tour here please ensure you have notified us. In case of emergencies You will be emailed your tour leaders name and contact number approximately one week prior to the tour start date. It is important you keep a record of this so that you can contact your tour leader if you have any issues meeting up with the tour. -

MY BOOKY WOOK a Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand

MY BOOKY WOOK A Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Stand-Up Russell Brand For my mum, the most important woman in my life, this book is dedicated to you. Now for God’s sake don’t read it. “The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between po liti cal parties either, but through every human heart” Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago “Mary: Tell me, Edmund: Do you have someone special in your life? Edmund: Well, yes, as a matter of fact, I do. Mary: Who? Edmund: Me. Mary: No, I mean someone you love, cherish and want to keep safe from all the horror and the hurt. Edmund: Erm . Still me, really” Richard Curtis and Ben Elton, Blackadder Goes Forth Contents iii Part I 1 April Fool 3 2 Umbilical Noose 16 3 Shame Innit? 27 4 Fledgling Hospice 38 5 “Diddle- Di- Diddle- Di” 50 6 How Christmas Should Feel 57 7 One McAvennie 65 8 I’ve Got a Bone to Pick with You 72 9 Teacher’s Whiskey 8186 94 10 “Boobaloo” 11 Say Hello to the Bad Guy Part II 12 The Eternal Dilemma 105111 13 Body Mist Photographic Insert I 14 Ying Yang 122 131 138146 15 Click, Clack, Click, Clack 16 “Wop Out a Bit of Acting” 17 Th e Stranger v Author’s Note Epigraph vii Contents 18 Is This a Cash Card I See before Me? 159 19 “Do You Want a Drama?” 166 Part III 20 Dagenham Is Not Damascus 179 21 Don’t Die of Ignorance 189 22 Firing Minors 201 Photographic Insert II 23 Down Among the Have-Nots 216 24 First-Class Twit 224 25 Let’s Not Tell Our Mums 239 26 You’re a Diamond 261 27 Call Me Ishmael. -

Translating Puns

TRANSLATING PUNS A STUDY OF A FEW EXAMPLES FROM BRITISH SERIES, BOOKS AND NEWSPAPERS MEMOIRE DE MASTER 1 ETUDES ANGLOPHONES AGNES POTIER-MURPHY Sous la direction de Mme Nathalie VINCENT-ARNAUD Année universitaire 2015-2016 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research director, Nathalie Vincent-Arnaud, for her continuous support, for her patience, motivation, and invaluable insights. I would also like to thank my assessor, Henri Le Prieult, for accepting to review my work and for all the inspiration I drew from his classes. Finally, I need to thank my family for supporting me throughout the writing of the present work. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Theoretical Background .................................................................................................................. 5 2.1. What is Humour? .................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Linguistic Humour: Culture and Metaphor ............................................................................. 7 2.3. Puns: a very specific humorous device ................................................................................... 9 2.4. Humour theories applied to translation ............................................................................... 10 3. Case study .................................................................................................................................... -

The Poetics of Sketch Comedy

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1994 The poetics of sketch comedy Michael Douglas Upchurch University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Upchurch, Michael Douglas, "The poetics of sketch comedy" (1994). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 368. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/8oh8-bt66 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS TTiis manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.