An Investigation Into the Genetic Architecture of Multiple System Atrophy and Familial Parkinson's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Gene Expression Data for Gene Ontology

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Robert Daniel Macholan May 2011 ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION Robert Daniel Macholan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Zhong-Hui Duan Dr. Chien-Chung Chan _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Chien-Chung Chan Dr. Chand K. Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Yingcai Xiao Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT A tremendous increase in genomic data has encouraged biologists to turn to bioinformatics in order to assist in its interpretation and processing. One of the present challenges that need to be overcome in order to understand this data more completely is the development of a reliable method to accurately predict the function of a protein from its genomic information. This study focuses on developing an effective algorithm for protein function prediction. The algorithm is based on proteins that have similar expression patterns. The similarity of the expression data is determined using a novel measure, the slope matrix. The slope matrix introduces a normalized method for the comparison of expression levels throughout a proteome. The algorithm is tested using real microarray gene expression data. Their functions are characterized using gene ontology annotations. The results of the case study indicate the protein function prediction algorithm developed is comparable to the prediction algorithms that are based on the annotations of homologous proteins. -

New Approaches to Functional Process Discovery in HPV 16-Associated Cervical Cancer Cells by Gene Ontology

Cancer Research and Treatment 2003;35(4):304-313 New Approaches to Functional Process Discovery in HPV 16-Associated Cervical Cancer Cells by Gene Ontology Yong-Wan Kim, Ph.D.1, Min-Je Suh, M.S.1, Jin-Sik Bae, M.S.1, Su Mi Bae, M.S.1, Joo Hee Yoon, M.D.2, Soo Young Hur, M.D.2, Jae Hoon Kim, M.D.2, Duck Young Ro, M.D.2, Joon Mo Lee, M.D.2, Sung Eun Namkoong, M.D.2, Chong Kook Kim, Ph.D.3 and Woong Shick Ahn, M.D.2 1Catholic Research Institutes of Medical Science, 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul; 3College of Pharmacy, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Purpose: This study utilized both mRNA differential significant genes of unknown function affected by the display and the Gene Ontology (GO) analysis to char- HPV-16-derived pathway. The GO analysis suggested that acterize the multiple interactions of a number of genes the cervical cancer cells underwent repression of the with gene expression profiles involved in the HPV-16- cancer-specific cell adhesive properties. Also, genes induced cervical carcinogenesis. belonging to DNA metabolism, such as DNA repair and Materials and Methods: mRNA differential displays, replication, were strongly down-regulated, whereas sig- with HPV-16 positive cervical cancer cell line (SiHa), and nificant increases were shown in the protein degradation normal human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT) as a con- and synthesis. trol, were used. Each human gene has several biological Conclusion: The GO analysis can overcome the com- functions in the Gene Ontology; therefore, several func- plexity of the gene expression profile of the HPV-16- tions of each gene were chosen to establish a powerful associated pathway, identify several cancer-specific cel- cervical carcinogenesis pathway. -

IA-2 Autoantibodies in Incident Type I Diabetes Patients Are Associated with a Polyadenylation Signal Polymorphism in GIMAP5

Genes and Immunity (2007) 8, 503–512 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1466-4879/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/gene ORIGINAL ARTICLE IA-2 autoantibodies in incident type I diabetes patients are associated with a polyadenylation signal polymorphism in GIMAP5 J-H Shin1, M Janer2, B McNeney1, S Blay1, K Deutsch2, CB Sanjeevi3, I Kockum4,A˚ Lernmark5 and J Graham1, on behalf of the Swedish Childhood Diabetes and the Diabetes Incidence in Sweden Study Groups 1Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada; 2Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, WA, USA; 3Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 4Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden and 5Department of Medicine, Robert H. Williams Laboratory, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA In a large case-control study of Swedish incident type I diabetes patients and controls, 0–34 years of age, we tested the hypothesis that the GIMAP5 gene, a key genetic factor for lymphopenia in spontaneous BioBreeding rat diabetes, is associated with type I diabetes; with islet autoantibodies in incident type I diabetes patients or with age at clinical onset in incident type I diabetes patients. Initial scans of allelic association were followed by more detailed logistic regression modeling that adjusted for known type I diabetes risk factors and potential confounding variables. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs6598, located in a polyadenylation signal of GIMAP5, was associated with the presence of significant levels of IA-2 autoantibodies in the type I diabetes patients. Patients with the minor allele A of rs6598 had an increased prevalence of IA-2 autoantibody levels compared to patients without the minor allele (OR ¼ 2.2; Bonferroni-corrected P ¼ 0.003), after adjusting for age at clinical onset (P ¼ 8.0 Â 10À13) and the numbers of HLA-DQ A1*0501-B1*0201 haplotypes (P ¼ 2.4 Â 10 À5) and DQ A1*0301-B1*0302 haplotypes (P ¼ 0.002). -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

The Cgmp-Dependent Protein Kinase 2 Contributes to Cone Photoreceptor Degeneration in the Cnga3-Deficient Mouse Model of Achroma

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article The cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase 2 Contributes to Cone Photoreceptor Degeneration in the Cnga3-Deficient Mouse Model of Achromatopsia Mirja Koch 1, Constanze Scheel 1, Hongwei Ma 2, Fan Yang 2, Michael Stadlmeier 3,† , Andrea F. Glück 3, Elisa Murenu 1,4, Franziska R. Traube 3 , Thomas Carell 3, Martin Biel 1, Xi-Qin Ding 2 and Stylianos Michalakis 1,4,* 1 Department of Pharmacy—Center for Drug Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, 81377 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (M.B.) 2 Department of Cell Biology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA; [email protected] (H.M.); [email protected] (F.Y.); [email protected] (X.-Q.D.) 3 Department of Chemistry, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, 81377 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.F.G.); [email protected] (F.R.T.); [email protected] (T.C.) 4 Department of Ophthalmology, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, 80336 Munich, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] † Present affiliation: Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, NJ 08544, USA. Abstract: Mutations in the CNGA3 gene, which encodes the A subunit of the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-gated cation channel in cone photoreceptor outer segments, cause total colour blindness, also referred to as achromatopsia. Cones lacking this channel protein are non- functional, accumulate high levels of the second messenger cGMP and degenerate over time after induction of ER stress. -

GANC (NM 001301409) Human Untagged Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for SC335588 GANC (NM_001301409) Human Untagged Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: GANC (NM_001301409) Human Untagged Clone Tag: Tag Free Symbol: GANC Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin Fully Sequenced ORF: >NCBI ORF sequence for NM_001301409, the custom clone sequence may differ by one or more nucleotides ATGGAAGCAGCAGTGAAAGAGGAAATAAGTCTTGAAGATGAAGCTGTAGATAAAAACATTTTCAGAGACT GTAACAAGATCGCATTTTACAGGCGTCAGAAACAGTGGCTTTCCAAGAAGTCCACCTATCAGGCATTATT GGATTCAGTCACAACAGATGAAGACAGCACCAGGTTCCAAATCATCAATGAAGCAAGTAAGGTTCCTCTC CTGGCTGAAATTTATGGTATAGAAGGAAACATTTTCAGGCTTAAAATTAATGAAGAGACTCCTCTAAAAC CCAGATTTGAAGTTCCGGATGTCCTCACAAGCAAGCCAAGCACTGTAAGGCTGATTTCATGCTCTGGGGA CACAGGCAGTCTGATATTGGCAGATGGAAAAGGAGACCTGAAGTGCCATATCACAGCAAACCCATTCAAG GTAGACTTGGTGTCTGAAGAAGAGGTTGTGATTAGCATAAATTCCCTGGGCCAATTATACTTTGAGCATC TACAGATTCTTCACAAACAAAGAGCTGCTAAAGAAAATGAGGAGGAGACATCAGTGGACACCTCTCAGGA AAATCAAGAAGATCTGGGCCTGTGGGAAGAGAAATTTGGAAAATTTGTGGATATCAAAGCTAATGGCCCT TCTTCTATTGGTTTGGATTTCTCCTTGCATGGATTTGAGCATCTTTATGGGATCCCACAACATGCAGAAT CACACCAACTTAAAAATACTGGTGATGGAGATGCTTACCGTCTTTATAACCTGGATGTCTATGGATACCA AATATATGATAAAATGGGCATTTATGGTTCAGTACCTTATCTCCTGGCCCACAAACTGGGCAGAACTATA GGTATTTTCTGGCTGAATGCCTCGGAAACACTGGTGGAGATCAATACAGAGCCTGCAGTAGAGTACACAC TGACCCAGATGGGCCCAGTTGCTGCTAAACAAAAGGTCAGATCTCGCACTCATGTGCACTGGATGTCAGA -

Reconstruction and Analysis of Gene Networks of Human

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Reconstruction and Analysis of Gene Networks of Human Neurotransmitter Systems Reveal Genes with Contentious Manifestation for Anxiety, Depression, and Intellectual Disabilities Roman Ivanov 1,2,*, Vladimir Zamyatin 1,2, Alexandra Klimenko 1,2 , Yury Matushkin 1,2, Alexander Savostyanov 1,2,3 and Sergey Lashin 1,2 1 Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] (V.Z.); [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (Y.M.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.L.) 2 Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 3 Institute of Physiology and Basic Medicine SB RAMS, 630117 Novosibirsk, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 August 2019; Accepted: 9 September 2019; Published: 11 September 2019 Abstract: Background: The study of the biological basis of anxiety, depression, and intellectual disabilities in humans is one of the most actual problems of modern neurophysiology. Of particular interest is the study of complex interactions between molecular genetic factors, electrophysiological properties of the nervous system, and the behavioral characteristics of people. The neurobiological understanding of neuropsychiatric disorders requires not only the identification of genes that play a role in the molecular mechanisms of the occurrence and course of diseases, but also the understanding of complex interactions that occur between these genes. A systematic study of such interactions obviously contributes to the development of new methods of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disorders, as the orientation to allele variants of individual loci is not reliable enough, because the literature describes a number of genes, the same alleles of which can be associated with different, sometimes extremely different variants of phenotypic traits, depending on the genetic background, of their carriers, habitat, and other factors. -

Myopia in African Americans Is Significantly Linked to Chromosome 7P15.2-14.2

Genetics Myopia in African Americans Is Significantly Linked to Chromosome 7p15.2-14.2 Claire L. Simpson,1,2,* Anthony M. Musolf,2,* Roberto Y. Cordero,1 Jennifer B. Cordero,1 Laura Portas,2 Federico Murgia,2 Deyana D. Lewis,2 Candace D. Middlebrooks,2 Elise B. Ciner,3 Joan E. Bailey-Wilson,1,† and Dwight Stambolian4,† 1Department of Genetics, Genomics and Informatics and Department of Ophthalmology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, United States 2Computational and Statistical Genomics Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States 3The Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, United States 4Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States Correspondence: Joan E. PURPOSE. The purpose of this study was to perform genetic linkage analysis and associ- Bailey-Wilson, NIH/NHGRI, 333 ation analysis on exome genotyping from highly aggregated African American families Cassell Drive, Suite 1200, Baltimore, with nonpathogenic myopia. African Americans are a particularly understudied popula- MD 21131, USA; tion with respect to myopia. [email protected]. METHODS. One hundred six African American families from the Philadelphia area with a CLS and AMM contributed equally to family history of myopia were genotyped using an Illumina ExomePlus array and merged this work and should be considered co-first authors. with previous microsatellite data. Myopia was initially measured in mean spherical equiv- JEB-W and DS contributed equally alent (MSE) and converted to a binary phenotype where individuals were identified as to this work and should be affected, unaffected, or unknown. -

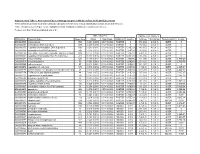

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Mitochondrial Protein Quality Control Mechanisms

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Mitochondrial Protein Quality Control Mechanisms Pooja Jadiya * and Dhanendra Tomar * Center for Translational Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19140, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.J.); [email protected] (D.T.); Tel.: +1-215-707-9144 (D.T.) Received: 29 April 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020; Published: 18 May 2020 Abstract: Mitochondria serve as a hub for many cellular processes, including bioenergetics, metabolism, cellular signaling, redox balance, calcium homeostasis, and cell death. The mitochondrial proteome includes over a thousand proteins, encoded by both the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. The majority (~99%) of proteins are nuclear encoded that are synthesized in the cytosol and subsequently imported into the mitochondria. Within the mitochondria, polypeptides fold and assemble into their native functional form. Mitochondria health and integrity depend on correct protein import, folding, and regulated turnover termed as mitochondrial protein quality control (MPQC). Failure to maintain these processes can cause mitochondrial dysfunction that leads to various pathophysiological outcomes and the commencement of diseases. Here, we summarize the current knowledge about the role of different MPQC regulatory systems such as mitochondrial chaperones, proteases, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, mitochondrial unfolded protein response, mitophagy, and mitochondria-derived vesicles in the maintenance of mitochondrial proteome and health. The proper understanding of mitochondrial protein quality control mechanisms will provide relevant insights to treat multiple human diseases. Keywords: mitochondria; proteome; ubiquitin; proteasome; chaperones; protease; mitophagy; mitochondrial protein quality control; mitochondria-associated degradation; mitochondrial unfolded protein response 1. Introduction Mitochondria are double membrane, dynamic, and semiautonomous organelles which have several critical cellular functions. -

Multiple System Atrophy: Genetic Or Epigenetic?

http://dx.doi.org/10.5607/en.2014.23.4.277 Exp Neurobiol. 2014 Dec;23(4):277-291. pISSN 1226-2560 • eISSN 2093-8144 Review Article A featured article of the special issue on Parkinsonian Syndrome Multiple System Atrophy: Genetic or Epigenetic? Edith Sturm and Nadia Stefanova* Division of Neurobiology, Department of Neurology, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck A-6020, Austria Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare, late-onset and fatal neurodegenerative disease including multisystem neurodegeneration and the formation of α-synuclein containing oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs), which present the hallmark of the disease. MSA is considered to be a sporadic disease; however certain genetic aspects have been studied during the last years in order to shed light on the largely unknown etiology and pathogenesis of the disease. Epidemiological studies focused on the possible impact of environmental factors on MSA disease development. This article gives an overview on the findings from genetic and epigenetic studies on MSA and discusses the role of genetic or epigenetic factors in disease pathogenesis. Key words: Multiple system atrophy, α-synuclein, neurodegeneration, genetics, epigenetics INTRODUCTION is characterized by selective wide spread neuronal cell loss, gliosis and oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) affecting In 1969 Graham and Oppenheimer suggested the term several structures of the central nervous system [3, 6, 7]. “multiple system atrophy” (MSA) to describe and combine Neuronal loss in MSA affects the striatum, substantia nigra a set of different disorders, including olivopontocerebellar pars compacta (SNpc), cerebellum, pons, inferior olives, central atrophy (OPCA), striatonigral degeneration (SND) and Shy- autonomic nuclei and the intermediolateral column of the spinal Drager syndrome [1].