Texas Landowner Changes and Trends Texas Land Trends | September 2017 Texas Landowner Changes and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Megaregions Reconsidered: Urban Futures and the Future of the Urban

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository 1 10 Megaregions reconsidered: urban futures and the future of the urban John Harrison and Michael Hoyler 10.1 An introduction to (more than just) a debate on megaregions We live in a world of competing urban, regional and other spatial imaginaries. This book’s chief concern has been with one such spatial imaginary – the megaregion. More particularly, its theme has been the assertion that the megaregion constitutes globalization’s new urban form. Yet, what is clear is that the intellectual and practical literatures underpinning the megaregion thesis are not internally coherent and this is the cause of considerable confusion over the precise role of megaregions in globalization. This book has offered one solution through its focus on the who, how and why of megaregions much more than the what and where of megaregions. In short, moving the debate forward from questions of definition, identification and delimitation to questions of agency (who or what is constructing megaregions), process (how are megaregions being constructed), and specific interests (why are megaregions being constructed) is the contribution of this book. The individual chapters have interrogated many of the claims and counter-claims made about megaregions through examples as diverse as California, the US Great Lakes, Texas and the Gulf Coast, Greater Paris, Northern England, Northern Europe, and China’s Pearl River Delta. But, as with any such volume, our approach has offered up as many new questions as it has provided answers. -

THE TEXAS TRIANGLE OFFICE MARKETS 60 Degrees of Separation

CBRE RESEARCH THE TEXAS TRIANGLE OFFICE MARKETS 60 Degrees of Separation SEPTEMBER 2016 CBRE RESEARCH THE TEXAS TRIANGLE OFFICE MARKETS 60 Degrees of Separation In Texas, six degrees of separation is really 60 -- not just because everything is bigger here, but because the physical locations of Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston and Austin form a triangle. Despite their geographic proximity, though, their office markets couldn’t be more different. CBRE RESEARCH | 2016 The Texas Triangle Office Market © 2016 CBRE, Inc. DALLAS TAKES OFF Dallas/Fort Worth is the largest office market in the state and the most diverse. Ranked first in the country for job growth over the past year, Dallas had record-smashing absorption in 2015 totaling 5.2 million sq. ft. That’s the equivalent of filling the Empire State Building nearly twice over. AUSTIN GETS TECHNICAL Austin is a major player in the tech world. Last year alone, 80% of the 119 relocations to or expansions in Austin came from the tech industry, driving explosive growth in the co-working sector. Companies are attracted to Austin’s young, socially-centric and tech-savvy demographic that has ignited an office building boom and transformed the Texas capital into an 18-hour city. SPACE CITY Houston’s nickname has taken on new meaning. Its 210 million-sq.- ft. office market is largely supported by energy-related tenants and is vulnerable to changes in commodity prices. Following the crude oil price downturn, sublease offerings have soared, thrusting office space availability up to 19.8%—a level not seen since the mid- 1990s—and stopping in its tracks a five-year consecutive streak of ferocious demand. -

Hyperloop Texas: Proposal to Hyperloop One Global Challenge SWTA 2017 History of Hyperloop

Hyperloop Texas: Proposal to Hyperloop One Global Challenge SWTA 2017 History of Hyperloop Hyperloop Texas What is Hyperloop • New mode of transportation consisting of moving passenger or cargo vehicles through a near-vacuum tube using electric propulsion • Autonomous pod levitates above the track and glides at 700 mph+ over long distances Passenger pod Cargo pod Hyperloop Texas History of Hyperloop Hyperloop Texas How does it work? Hyperloop Texas How does it work? Hyperloop Texas History of Hyperloop Hamad Port Doha, Qatar Hyperloop Texas Hyperloop One Global Challenge • Contest to identify and select • 2,600+ registrants from more • Hyperloop TX proposal is a locations around the world with than 100 countries semi-finalist in the Global the potential to develop and • AECOM is a partner with Challenge, one of 35 selected construct the world’s first Hyperloop One, building test from 2,600 around the world Hyperloop networks track in Las Vegas and studying connection to Port of LA Hyperloop Texas Hyperloop SpaceX Pod Competition Hyperloop Texas QUESTION: What happens when a megaregion with five of the eight fastest growing cities in the US operates as ONE? WHAT IS THE TEXAS TRIANGLE? THE TEXAS TRIANGLE MEGAREGION. DALLAS Texas Triangle DALLAS comparable FORT FORT WORTH to Georgia in area WORTH AUSTIN SAN ANTONIO HOUSTON LAREDO AUSTIN SAN ANTONIO HOUSTON LAREDO TRIANGLE HYPERLOOP The Texas Triangle HYPERLOOP FREIGHT Hyperloop Corridor The proposed 640-mile route connects the cities of Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, and Houston with Laredo -

City of Bryan Budget Proposal

CITY OF BRYAN FY PROPOSED ANNUAL BUDGET 2020 CITY OF BRYAN, TEXAS ANNUAL OPERATING BUDGET FOR FISCAL YEAR 2019-2020 This budget will raise more revenue from property taxes than last year’s budget by an amount of $2,343,717 which is a 6.6% increase from last year’s budget. The property tax revenue to be raised from new property added to the tax roll this year is $903,943. This page left blank intentionally. City of Bryan, Texas Fiscal Year 2020 Adopted Annual Budget Table of Contents Transmittal Letter City Manager’s Transmittal Letter ........................................................................................................................ i Introduction Principal City Officials ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Budget Calendar .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Organizational Chart ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Single Member (City Council) District Map .......................................................................................................... 7 Strategic Plan ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Strategic Areas of Emphasis by Department .................................................................................................... -

THE TEXAS WAY of URBANISM the Texas Way of Urbanism

THE TEXAS WAY OF URBANISM the texas way of urbanism center for opportunity urbanism 1 the texas way of urbanism The Center for Opportunity Urbanism (COU) is a 501(c)(3) national think tank. COU focuses on the study of cities as generators of upward mobility. COU’s mission is to change the urban policy discussion, both locally and globally. We are seeking to give voice to a ‘people oriented’ urbanism that focuses on economic opportunity, upward mobility, local governance and broad based growth that reduces poverty and enhances quality of life for all. For a comprehensive collection of COU publications and commentary, go to www.opportunityurbanism.org. 2 the texas way of urbanism CONTENTS Texas Urbanism Bios ........................................................................3 The Emergence of Texas Urbanism; The Triangle Takes Off .....................................5 The Texas Urban Model .....................................................................7 The Dallas Way Of Urban Growth........................................................... 12 Houston, City of Opportunity Center for Opportunity Urbanism .............................. 19 Opportunity Urbanism: The Tech Edition ................................................... 28 San Antonio: Growth And Success In The Mexican-American Capital ......................... 37 Military Employment and the Upward Mobility of Latinos in San Antonio ..................... 47 A summary of the analysis and motivators of growth in the Austin - San Antonio corridor. ...... 49 Endnotes ................................................................................. 57 3 texas urbanism bios TEXAS URBANISM BIOS John C. Beddow, Author – served as publisher of the Klaus Desmet, Author – is the Altshuler Centennial Houston Business Journal from 1998 to last year. He suc- Interdisciplinary Professor of Cities, Regions and Global- cessful turned the HBJ fromjust a weekly print product to ization at Southern Methodist University and a Research a 24/7 digital first multi-platform business news channel. -

MEGAREGIONAL SYNERGY the Intersection of Teaching, Research, and Practice at the University of Texas

MEGAREGIONAL SYNERGY The Intersection of Teaching, Research, and Practice at the University of Texas Forum Texas Chapter of the American Planning Association’s State Conference Presented by Dr. Talia McCray and Billy Fleming Fort Worth, TX 10.4.2012 MEGAREGIONAL SYNERGY Outline 1. Developing the Nation’s First Course on MegaRegions Dr. Talia McCray 2. New Planners and the MegaRegional Opportunity Billy Fleming DEVELOPING THE NATION’S FIRST COURSE ON MEGAREGIONS Mega-Regional Synergy at UT-Austin Dr. Talia McCray 10.4.2012 Origins of the term “Megaregion” • Jean Gottmann, 1964 – French geographer coined the phrase “Megalopolis” – Very Large City. First applied to the Northeast Corridor – Boston to DC. Region defined as “discrete and independent, uniquely tied to each other through the intermeshing of their suburban zones, acting in some ways as a unified super- city: a megalopolis” • Global City-region (Scott, 2001) – Term has been used by urbanists, economists, and urban planners since the 1950s to mean not just the administrative area of a recognizable city or conurbation but also its hinterland that is often far larger. Economic ties may include rural areas, suburbs, or county towns. What is a Megaregion? • Networks of metropolitan regions with shared – Economies – Infrastructure – Natural resource systems • Stretching over distances of roughly 300 miles - 600 miles in length Source: Hagler & Todorovich, 2009 Definitions of a Megaregion • A chain of roughly adjacent metropolitan areas • Composed of two or more cities • Clustered network of American cities whose population ranges are or are projected between 7 to 63 million by the year 2025 • A polycentric agglomeration of cites and their lower-density hinterlands Spatial Linkages • Economics: Interlocking economic systems • Environment: Shared natural resources and ecosystems • Infrastructure: Common transportation systems How many Megaregions are there? Between 10 and 11, depending on the criteria Regional Plan Association & America 2050 – 11 Megaregions The image cannot be displayed. -

Forecast of the Texas Labor Market 2012-2015

Growth Abounds A FORECAST OF THE TEXAS LABOR MARKET 2012-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward . 1 Setting the Stage: Changing Economies. 3 Major Texas Industries . 7 Texas Economists Predicting Job Growth . 15 Texas Regional Snapshots . .20 Statewide . .31 Epilogue. 36 The Labor Market & Career Information department of the Texas Workforce Commission publishes this report every other year. This year, this report covers four components: 1) Employment forecasts for Texas by the contracted economics firm of IHS Global Insights 2) Employment forecasts for specific industries by the IHS Global Insights economists 3) National and regional economic insights by Texas economists 4) Anticipated employment growth in specific industries highlighted by region FORWARD Total employment in Texas should rise by 2.1% in 2013 and another 2.3% growth in 2014 and then another 2.4% growth in 2015, according to economists from the highly respected IHS Global Insights, an economic forecasting firm. The economists at IHS Global Insights have pulled employment data for different industries and regions in Texas then applied their national and global economic modeling to the Texas employment data to forecast employment levels in different industries and regions of the Lone Star State. For additional context and insight, economists at Texas universities and the Federal Reserve Bank were also surveyed regarding their Texas employment forecasts. The results are contained in this report. Proving that economic forecasting is equal parts art and science, the economists at Texas universities and other institutions are forecasting a broad range of job growth in the Lone Star State. These Texas economists polled are forecasting total employment growth of 0.5% to 2.8% in 2013 followed by forecasts of employment growth of 0.5% to 3.1% in 2014. -

Globalization and the Texas Metropolises

GLOBALIZATION AND THE TEXAS METROPOLISES: COMPETITION AND COMPLEMENTARITY IN THE TEXAS URBAN TRIANGLE A Dissertation by JOSÉ ANTÓNIO DOS REIS GAVINHA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Major Subject: Geography GLOBALIZATION AND THE TEXAS METROPOLISES: COMPETITION AND COMPLEMENTARITY IN THE TEXAS URBAN TRIANGLE A Dissertation by JOSÉ ANTÓNIO DOS REIS GAVINHA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Daniel Z. Sui Committee Members, Robert S. Bednarz Hongxing Liu Michael Neuman Head of Department, Douglas J. Sherman December 2007 Major Subject: Geography iii ABSTRACT Globalization and the Texas Metropolises: Competition and Complementarity in the Texas Urban Triangle. (December 2007) José António dos Reis Gavinha, B.A., Universidade do Porto; M.Sc., University of Toronto Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Daniel Z. Sui This dissertation examines relationships between cities, and more specifically the largest Texas cities, and the global economy. Data on headquarters location and corporation sales over a 20-year period (1984-2004) supported the hypothesis that globalization is not homogeneous, regular or unidirectional, but actually showed contrasted phases. Texas cities have been raising in global rankings, due to corporate relocations and, to lesser extent, the growth of local activities. By year 2004, Dallas and Houston ranked among the top-20 headquarters cities measured by corporation sales The Texas Urban Triangle had one of the major global concentrations of oil- and computer-related corporation headquarters; conversely, key sectors like banking, insurance and automotive were not significant. -

Megaregions: Literature Review of the Implications for U.S

Megaregions: Literature Review of the Implications for U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Transportation Planning For U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Federal Highway Administration Dr. Catherine L. Ross, Principal Investigator CENTER FOR QUALITY GROWTH AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT at the GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2008 Megaregions: Literature Review of the Implications for Infrastructure Investment and Transportation Planning Project Title: Megaregions and Transportation Planning (FHWA-BAA-HEPP-02-2007) Deliverable 1b: a report comprised of case studies that summarize the application of large-scale regionalism in the U.S. and abroad and the existing literature on megaregions Submitted to: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Office of Planning, HEPP-20 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Point of Contact: Supin Yoder Submitted by: Georgia Tech Research Corporation (A Non-profit, State Controlled Institution of Higher Education) Principal Investigator: Dr. Catherine L. Ross ([email protected]) Co-PIs: Jason Barringer, Jiawen Yang Researchers: Myungje Woo, Jessica Doyle, Harry West, with Adjo Amekudzi and Michael Meyer Georgia Institute of Technology College of Architecture Center for Quality Growth and Regional Development (CQGRD) 760 Spring Street, Suite 213 Atlanta, GA 30332-0790 Phone: (404) 385-5133, FAX: (404) 385-5127 ii Megaregions: Literature Review of the Implications for U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Transportation Planning Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 SECTION I. OVERVIEW 9 A. Research Background 9 B. Report Organization 10 SECTION II. FOUNDATIONS AND DELINEATION APPROACHES 11 A. Examining the Literature 11 1. Regionalism 11 2. Globalization 12 3. Global Climate Change 13 4. Economic Geography 17 5. -

Copyright by Brendan Michael Goodrich 2018

Copyright by Brendan Michael Goodrich 2018 The Report Committee for Brendan Michael Goodrich Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Report: Transit-Oriented Development in the Texas Triangle Megaregion: An Inventory of Planning Practices and Infrastructure, and a Synthesis of Stakeholder Perspectives APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Ming Zhang, Supervisor Junfeng Jiao Transit-Oriented Development in the Texas Triangle Megaregion: An Inventory of Planning Practices and Infrastructure, and a Synthesis of Stakeholder Perspectives by Brendan Michael Goodrich Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Community and Regional Planning The University of Texas at Austin August 2018 Abstract Transit-Oriented Development in the Texas Triangle Megaregion: An Inventory of Planning Practices and Infrastructure, and a Synthesis of Stakeholder Perspectives Brendan Michael Goodrich, MSCRP The University of Texas at Austin, 2018 Supervisor: Ming Zhang While most Texas Triangle planning agencies at the state, regional, and local level agree that transit-oriented development (TOD) would benefit their communities, less than ¼ report having even adopted a definition for TOD for their jurisdiction. As a result, most of the region’s 181 TOD-ready sites remain underdeveloped. Planning agencies need guidance in developing policies and guidelines that support the construction of quality TOD at rapid transit stations. This research set forth to inventory TOD in the Texas Triangle, as well as identify the reasons for successes and failures around the megaregion. Through desktop research, surveys, and interviews, this research found that public agencies crucially need guidance on new and useful Texas value capture mechanisms—especially TIRZs and TRZs—which could fund needed capital projects for station areas and for transit lines. -

The Texas Triangle As Megalopolis

HoustonBusiness A Perspective on the Houston Economy FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS • HOUSTON BRANCH • APRIL 2004 them to seek out roles that The Texas Triangle complemented economic strengths developing elsewhere as Megalopolis in the Triangle.1 Where one city was strong, the others would be weak, so the cities’ mature industrial structures could fit together neatly, like pieces of The January issue of Hous- a puzzle, with little overlap. If the Triangle cities ton Business proposed that the A comparison of the cities’ are really a megalopolis, Texas Triangle metro areas of strengths indicated such indus- Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, trial complementarity exists, divided into four parts Houston and San Antonio exist and statistical tests strongly by geography and as distinct cities largely because confirmed the apparent com- of Texas geography. With a plementarity is no illusion. history, their long, navigable river reaching This article looks at the the heart of the state or a deep same puzzle, but from a differ- complementarity saltwater bay or other inlet ent angle. If the Triangle cities implies we can add making Waco or Temple a sea- are really a megalopolis, divided port, many of the roles played into four parts by geography the four together and by the Triangle cities could and history, their complemen- have been combined at a single tarity implies we can add the approximate what location. Combining Houston’s four together and approximate would have developed port, Dallas’ inland distribution what would have developed in function, San Antonio’s reach that other reality with a long in that other reality into deep South Texas and river or saltwater bay. -

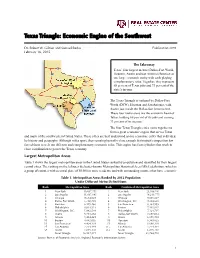

Texas Triangle: Economic Engine of the Southwest

Texas Triangle: Economic Engine of the Southwest Dr. Robert W. Gilmer and Samuel Redus Publication 2091 February 16, 2015 The Takeaway Texas’ four largest metros (Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Austin and San Antonio) function as one large economic entity with each playing complementary roles. Together, they represent 68 percent of Texas jobs and 73 percent of the state’s income. The Texas Triangle is outlined by Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW), Houston and San Antonio, with Austin just inside the Dallas-San Antonio line. These four metro areas are the economic heart of Texas, holding 68 percent of its jobs and earning 73 percent of its income. The four Texas Triangle cities come together to form a great economic engine that serves Texas and much of the southwestern United States. These cities are best understood as one economic entity that is divided by history and geography. Although miles apart, they remain physically close enough that mutual competition has forced them to seek out different and complementary economic roles. This engine has four cylinders that work in close coordination to power the Texas economy. Largest Metropolitan Areas Table 1 shows the largest metropolitan areas in the United States ranked by population and identified by their largest central cities. The ranking on the left uses the better-known Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) definition, which is a group of counties with a central place of 50,000 or more residents, and with surrounding counties that have economic Table 1. Metropolitan Areas Ranked by 2012 Population Under Different Metro Definititions Rank Metropolitan Area Rank Combined Metropolitan Area 1 New York 19,837,753 1 New York 23,368,541 2 Los Angeles 13,037,045 2 Los Angeles 18,213,775 3 Chicago 9,514,059 3 Chicago 9,891,237 4 Dallas-Fort Worth 6,702,801 4 Washington, D.C.