Black Women in Film When and Where They Enter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CPY Document

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Offce of the City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council APR 1 2 200l Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C.D.No.13! SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk FOREST WHITAKER RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square northerly of and between numbered locations 32K and 21K as shown on Sheet 8 of Plan P-35375 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Forest Whitaker at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce of the Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date ofthe ceremony on April 16, 2007. FISCAL IMP ACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRASM1TT ALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated March 26, 2007, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2 - C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee ofthe Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Forest Whitaker. The ceremony is scheduled for Monday,April 16, 2007 at 11 :30 a.m. The communicant's request is in aecordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters

Still Waiting to Exhale: An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamila D. Smith, B.A., MFA College of Education and Human Ecology The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Elaine Richardson, Advisor Professor Adrienne D. Dixson Professor Carmen Kynard Professor Wendy Smooth Professor Cynthia Tyson Copyright by Jamila D. Smith 2012 Abstract This dissertation consists of a nine month, three-state ethnographic study on the intersectional effects of race, age, gender, and place in the lives of fourteen Black mothers and daughters, ages 15-65, who attempt to analyze and critique the multiple and competing notions of Black womanhood as “at risk” and “in crisis.” Epistemologically, the research is grounded in Black women’s narrative and literacy practices, and fills a gap in the existing literature on Black girlhood and Black women’s lived experiences through attention to the development of mother/daughter relationships, generational narratives, societal discourse, and othermothering. I argue that an in-depth analysis and critique of the dominant “at risk” and “in crisis” discourse is necessary to understand the conversations that are and are not taking place between Black mothers and daughters about race, gender, age, and place; that it is important to understand the ways in which Black girls respond to media portrayals and stereotypes; and that it is imperative that we closely examine the existing narratives at play in the everyday lives of intergenerational Black girls and women in Black communities. -

Feature Films for Education Collection

COMINGSOON! in partnership with FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Hundreds of full-length feature films for classroom use! This high-interest collection focuses on both current • Unlimited 24/7 access with and hard-to-find titles for educational instructional no hidden fees purposes, including literary adaptations, blockbusters, • Easy-to-use search feature classics, environmental titles, foreign films, social issues, • MARC records available animation studies, Academy Award® winners, and • Same-language subtitles more. The platform is easy to use and offers full public performance rights and copyright protection • Public performance rights for curriculum classroom screenings. • Full technical support Email us—we’ll let you know when it’s available! CALL: (800) 322-8755 [email protected] FAX: (646) 349-9687 www.Infobase.com • www.Films.com 0617 in partnership with COMING SOON! FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Here’s a sampling of the collection highlights: 12 Rounds Cocoon A Good Year Like Mike The Other Street Kings 12 Years a Slave The Comebacks The Grand Budapest Little Miss Sunshine Our Family Wedding Stuck on You 127 Hours Commando Hotel The Lodger (1944) Out to Sea The Sun Also Rises 28 Days Later Conviction (2010) Grand Canyon Lola Versus The Ox-Bow Incident Sunrise The Grapes of Wrath 500 Days of Summer Cool Dry Place The Longest Day The Paper Chase Sunshine Great Expectations The Abyss Courage under Fire Looking for Richard Parental Guidance Suspiria The Great White Hope Adam Crazy Heart Lucas Pathfinder Taken -

An Analysis of the Permeation of Racial Stereotypes in Top-Grossing Black

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Honors College Theses 8-2016 Still Waiting: An analysis of the permeation of racial stereotypes in top-grossing Black Romance films from the 1960s to the 2000s Jasmine Boyd-Perry University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/honors_theses Part of the African American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Boyd-Perry, Jasmine, "Still Waiting: An analysis of the permeation of racial stereotypes in top-grossing Black Romance films from the 1960s to the 2000s" (2016). Honors College Theses. Paper 25. This Open Access Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Still Waiting: An analysis on the permeation of racial stereotypes in top grossing Black Romance films from the 1960’s to the 2000’s Jasmine Boyd-Perry Honors College University of Massachusetts Boston August 26, 2016 Advisors: Philip Kretsedemas Department of Sociology University of Massachusetts Boston Megan Rokop Honors College University of Massachusetts Boston 1 Table of Contents Introduction p. 3 Methods p. 10 Results p. 13 Discussion p. 33 References p. 39 Appendix: Plot Summaries of each film p. 40 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Philip Kretsedemas, Megan Rokop, Rajini Srikanth, Ralston Grose, Hannah Brown, Emmanuel Oppong-Yeboah, Catienna Regis, Soren DuBon, Samantha Nam-Krane, my mother Rashida Boyd and my nana Judy Boyd. -

Programming Ideas

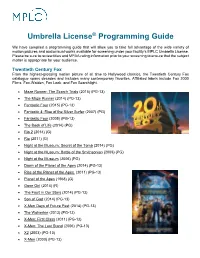

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

The Inventory Ofthe Forest Whitaker Collection #1676

The Inventory ofthe Forest Whitaker Collection #1676 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Whitaker, Forest #1676 10/7/08 Preliminary Listing I. Manuscripts. A. Scripts, TS screenplays unless noted. Box 1 1. "The Air I Breathe," by Jieho Lee and Bob de Rosa, 2 drafts, 115- 121 p., 8/8/05 - 12/29/05. [F. 1] 2. "American Gun," by Arie Avelino and Steven Bagatourian, 7 drafts, approx. 120 p. each, 1/14/08 - 6/29/04. [F. 2-8] 3. "Black Jab" (alternate title: "Mississippi Dawn"), by Alfred Gough, Miles Millar, and Dawnn Lewis, 3 drafts, 12/19/97, 3/30/98, 1/18/98, includes holograph notes. [F. 9-10] 4. "Door to Door," by William H. Macy and Steven Schachter, 104 p., 5/18/00. [F. 11] 5. "The Facts About Kate," by Lori Lakin, 5 drafts, approx. 120 p. each, 2/11/02 - 1/31/03. [F. 12-16] 6. "First Daughter," by Kate Kondell, 5 drafts, approx. 110 p., 4/1/02- 6/12/03. [F. 17-19] a. Mini-script, 103 p., 5/17/03. [E. 1] 7. "The Great Debaters," by Robert Eisele, 6 drafts, approx. 15-140 p., 5/1/07-5/14/07; includes holograph notes. [F. 20-24] Box2 a. Ibid. [F. 1] 8. "Hurricane Season," by Robert Eisele, 8 drafts, approx. 115 p. each, 2/14/08-June, 2008; includes holograph notes; correspondence. [F. 2-1 OJ a. 7 drafts, n.d. [F. 11-16] b. Text fragments with holograph notes, approx. 400 p. [F. 17-21] 9. "Last King of Scotland," by Peter Morgan, approx. -

Waiting to Exhale: African American Women and Adult Learning Through Movies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 261 CE 084 294 AUTHOR Rogers, Elice E. TITLE Waiting to Exhale: African American Women and Adult Learning Through Movies. PUB DATE 2002-05-00 NOTE 8p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Adult Education Research Conference (43rd, Raleigh, NC, May 24-26, 2002). AVAILABLE FROM Adult and Community College Education, Box 7801, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695-7801 ($30). For full text: http:// www. ncsu .edu /ced /acce /aerc /start.pdf PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Adult Learning; Adult Literacy; Black Culture; *Blacks; Critical Thinking; Females; *Films; *Informal Education; *Popular Culture; Race; Racial Differences; Sex; Sex Differences; Social Class; Social Differences; *Womens Education IDENTIFIERS African Americans ABSTRACT Scholars have addressed adults and the impact of popular culture on adult learning, but little attention has been directed toward the relationship between adult learning and African Americans. Most specifically, minimal information is related to adult learning that evolves as a result of popular culture influences. Popular culture promotes cultures of learning and teaches and facilitates a more informed literate citizenry. As a form of popular culture, movies inform adults about race, class, and gender issues. The movie, "Waiting to Exhale," challenges adult audiences to think critically about race, class, and gender experiences as they occur in the social context and examine problems that foster intergroup and community misunderstandings. It explores the complex themes of race, class, and gender and the quest for loving adult relationships amid the struggle to be successful African American women. -

Cultural Awareness in Language Studies

CUW'UI<A, 1.13NOUAJB Y REPRESEN'I'ACI~N/ CULTUHE, LANGUACEAND HEPRESENTATION. VOL 1 \ 2004, pp. 127-136 INI!VIS'I)\ 11% I!SI'UI>IOS CUUI'URALES VE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDlES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSfZATJAUME I Cultural Awareness in Language Studies ROTA LENKAUSKIENE, VILMANTE LIUBINIENE KAUNAS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY f 1 presente estudio de campo aborda 10s problemas de comunicación que pueden surgir en el contexto de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera. Especqicamente, se ana- liza la necesidad de introducir el contexto cultural de la lengua de destino para superar las posibles dqficiencias comunicativas, en el ámbito de la instrucción de la lengua inglesa a estudiantes universitarios lituanes. Tras ponderar las diversas reacciones de 10s estudiantes muestreados ante la exposición a la cultura anglosajona, llevada a cabo con la proyeccidn y posterior discusión de dos películas, Animal Farm (Rebelión en la granja) y Waiting to Exhale (Esperando un respiro), 10s autores concluyen que el concepto de ccconocimientou o ccconciencia cultural, constituye un elemento fundamental en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera, cuya ausencia puede provocar el fracaso en la comunicación. Sin embargo, la enseñanza de tal noción debe integrarse y complementarse con el espectro cognitivo de la lengua y cultura del hablante nativo si se pretende conseguir una habilidad comunicativa ~f~cazen la lengua de destino. 1. Introduction Globalization is creating new needs for effective communication across cultures, and is also requiring new and different types of communication skills for the increasing number of international interactions taking place through new technologies. The impact of new technologies has put forward new challenges. -

Ouagadougou '95 African Cinema

40 Acres And AMule Filmworks a OW ACCEPTING SCRIPTS © Copyright Required DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT • 8 ST. FELIX STREET • BROOKLYN, NY 11217 6 Close Up One in San Francisco and the other London. Two black women make J?1usic for the movies. 9 World View Ouagadougou '95: Mrican Cinema, Heart and Soul(d), Part I CLAIRE ANDRADE WATKINS In the first ofa two part article) Claire Andrade Watkins shares insights on the African Cinema scene from FESPACO. Black Film Review Volume 8, Number 3 12 Film Clips ]ezebel Filmworks does Hair. .. FILMFEST DC audience pick... VOices Corporate & Editorial Offices Against Violence. 2025 Eye Street, NW Suite 213 Washington, D.C. 20006 Tel. 202.466.2753 FEATURES Fax. 202.466.8395 e-mail 14 Hot Black Books Set Hollywood on Fire [email protected] TAREsSA STOVALL Editor-in-Chief Will the high sales ofblack novels translate into box office heat? Leasa Farrar-Frazer Consulting Editor 19 We Are the World: Black Film and the Globalization of Racism Tony Gittens (Black Film Institute, University of the District of CLARENCE LUSANE Columbia) What we need to know about who owns and controls the global images of Founding Editor black people. David Nicholson Art Direction & Design Lorenzo Wilkins for SHADOWORKS INTERVIEWS Contributing Editors TaRessa Stovall 22 APraise Poem: Filming the Life of Andre Lorde PAT AUFDERHEIDE Contributors Pat Aufderheide Producer Ada Gay Griffin shares her thoughts on the experience. Rhea Combs Eric Easter Joy Hunter 25 Live From The Madison Hotel Clarence Lusane Eric Easter talks with Carl Franklin) Walter Mosely and the Hughes Brothers Denise Maunder Marie Theodore Claire Andrade Watkins Co-Publisher DEPARTMENTS One Media, Inc. -

Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - the AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION

AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA CINEMA AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA The history of the African-American Cinema is a harsh timeline of racism, repression and struggle contrasted with film scenes of boundless joy, hope and artistic spirit. Until recently, the study of the "separate cinema" (a phrase used by historians John Kisch and Edward Mapp to describe the segregation of the mainstream, Hollywood film community) was limited, if not totally ignored, by writers and researchers. The uphill battle by black filmmakers and performers, to achieve acceptance and respect, was an ugly blot on the pages of film history. Upon winning his Best Actor Oscar for LILLIES OF THE FIELD (1963), Sidney Poitier accepted, on behalf of the countless unsung African-American artists, by acknowledging the "long journey to this moment." This emotional, heartbreaking and inspiring journey is vividly illustrated by the latest acquisition to the Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION. The valuable research material, housed in this collection, includes over 300 pressbooks (illustrated campaign and advertising catalogs sent to theatre owners), press kits (media packages including biographies, promotional essays and illustrations), programs and over 1000 photographs and slides. The journey begins with the blatant racism of D.W. Griffith's THE BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), a film respected as an epic milestone, but reviled as the blueprint for black film stereotypes that would appear throughout the 20th century. Researchers will follow African-American films through an extended period of stereotypical casting (SONG OF THE SOUTH, 1946) and will be dazzled by the glorious "All-Negro" musicals such as STORMY WEATHER (1943), ST.LOUIS BLUES (1958) and PORGY AND BESS (1959). -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

Voi.. L ---- No. 4- r’ebruary 15, 1996 Cosby Center Generates Excitement By Dorlisa Goodrich ing room. Editor-in-Chief The third floor is home The days surrounding to the Department of En the opening of the Cosby glish, the Writing Center, a Center will be jam-packed faculty meeting room, and with events in order to pay classrooms. As one jour tribute to the Drs. William neys to the fourth floor, and Camille Cosby. check out the Department of On Thursday, Feb. 22, History, international Af Ms. Nettie Washington fairs Center, the Depart Douglass, heir ofBookerT. ments of Modern Foreign Washington and Frederick Language, Religion and Phi- Douglass, will speak at Con losophy, and the Study vocation. At noon, all stu Abroad Program. dents are invited to a ribbon cutting ceremony at the Cen ter. Tours of the building will be conducted by desig students will be able to meet facilities will be used for nated tour guides and that with them in Sisters Chapel. educational and cultural pur evening a student tribute will A Dedication and Celebra poses. be held. Entitled "Celebrat tion Program will immedi On the lower level, ing the Humanities: TheTalk- ately follow at 4 PM in the one will find the Educational ing Tribute," students will Cosby Center Auditorium. Media Center, Foreign Lan be treated to a night of enter guage Labs, a museum lab, tainment and refreshments. lecture rooms and class Friday will be devoted What’s rooms. The ground level to "Celebrating the Humani houses the auditorium and ties: A Map of Life Long museum. -

Soul Food 1997 Watch

Soul food 1997 watch click here to download Watch Soul Food Online Full Movie, soul food full hd with English subtitle. Stars: Vivica A Fox, Nia Long, Vanessa Williams. Find out where to watch, buy, and rent Soul Food Online on Moviefone. Soul Food () Watch Online · Soul George Tillman says Soul Food is based in part on his own family, and I believe him, because he seems to know the. Find trailers, reviews, synopsis, awards and cast information for Soul Food () - George Tillman, Jr. on AllMovie - This hit domestic comedy-drama concerned. Soul Food Poster · Trailer. | Trailer. 1 VIDEO | 22 IMAGES · Watch Now Irma P. Hall in Soul Food () Vivica A. Fox, Nia Long, and Vanessa Williams in. Soul Food launched the directing career of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, native George Tillman, Jr., who based Sep 26, wide Watch it now. Soul Food Poster 1. Soul Food () on Netflix. R mins Click the "Watch on Netflix" button to find out if Soul Food is playing in your country. IMDB Score. Buy Soul Food: Read Movies & TV Reviews - www.doorway.ru Soul Food RSubtitles and Closed Captions Rentals include 30 days to start watching this video and 48 hours to finish once started. Rent Movie HD $ Buy Movie. Check out the exclusive www.doorway.ru movie review and see our movie rating for Soul Food. ; Movie; R; Drama; 68 METASCORE Where to Watch. Buy Soul Food: Read Movies & TV Reviews - www.doorway.ru Rentals include 30 days to start watching this video and 48 hours to finish once started. Rent. Soul Food movie reviews & Metacritic score: An ensemble drama set around the abundant table of Chicago family matriarch Mother Joe, TV-MA, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation | Release Date: September 26, Watch Now .