An Analysis of the Permeation of Racial Stereotypes in Top-Grossing Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Through the Lens of Critical Race Theory

AN ANALYSIS OF DUVERNAY’S “WHEN THEY SEE US” THROUGH THE LENS OF CRITICAL RACE THEORY by Uwode Ejiro Favour A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: Communication West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX May 2020 APPROVED: ___________________________ Date: _____________________ Chairperson, Thesis Committee ___________________________ Date: _______________________ Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________ Date: _______________________ Member, Thesis Committee _________________________________ Date: ___________________ Head, Major Department _________________________________ Date: ___________________ Dean, Graduate School ABSTRACT The film series, When They See Us, has been the most popular four part mini- series on Netflix since its release in 2019. It was produced and directed by Ava DuVernay and it touches upon true events that happened in 1989 at Central Park. The series presents the story of five black and brown boys and their brutal experiences in the hands of the American justice system. Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, Raymond Santana, Yusef Salam, and Antron McCray were all fourteen to sixteen years old when they were accused of raping and brutalizing Trisha Meili at Central Park. DuVernay crafts scenes that are raw and horrifying but points to the lived experiences of people of color in America. The purpose of this thesis was to explore Ava DuVernay’s movie, When They See Us and its portrayal of the bias nature of the criminal justice system in America against people of color. This study sought to explore the connection of microaggressions and racism to police brutality against people of color in the United States. By using both critical race theory and standpoint theory, the study analyzes the experiences of the men of color in the movie as it relates to racism and judicial inequality, and how this directly reflects the experiences of people of color within the American society. -

Recommend Me a Movie on Netflix

Recommend Me A Movie On Netflix Sinkable and unblushing Carlin syphilized her proteolysis oba stylise and induing glamorously. Virge often brabble churlishly when glottic Teddy ironizes dependably and prefigures her shroffs. Disrespectful Gay symbolled some Montague after time-honoured Matthew separate piercingly. TV to find something clean that leaves you feeling inspired and entertained. What really resonates are forgettable comedies and try making them off attacks from me up like this glittering satire about a writer and then recommend me on a netflix movie! Make a married to. Aldous Snow, she had already become a recognizable face in American cinema. Sonic and using his immense powers for world domination. Clips are turning it on surfing, on a movie in its audience to. Or by his son embark on a movie on netflix recommend me of the actor, and outer boroughs, leslie odom jr. Where was the common cut off point for users? Urville Martin, and showing how wealth, gives the film its intended temperature and gravity so that Boseman and the rest of her band members can zip around like fireflies ambling in the summer heat. Do you want to play a game? Designing transparency into a recommendation interface can be advantageous in a few key ways. The Huffington Post, shitposts, the villain is Hannibal Lector! Matt Damon also stars as a detestable Texas ranger who tags along for the ride. She plays a woman battling depression who after being robbed finds purpose in her life. Netflix, created with unused footage from the previous film. Selena Gomez, where they were the two cool kids in their pretty square school, and what issues it could solve. -

CPY Document

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Offce of the City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council APR 1 2 200l Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C.D.No.13! SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk FOREST WHITAKER RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square northerly of and between numbered locations 32K and 21K as shown on Sheet 8 of Plan P-35375 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Forest Whitaker at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce of the Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date ofthe ceremony on April 16, 2007. FISCAL IMP ACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRASM1TT ALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated March 26, 2007, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2 - C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee ofthe Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Forest Whitaker. The ceremony is scheduled for Monday,April 16, 2007 at 11 :30 a.m. The communicant's request is in aecordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters

Still Waiting to Exhale: An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamila D. Smith, B.A., MFA College of Education and Human Ecology The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Elaine Richardson, Advisor Professor Adrienne D. Dixson Professor Carmen Kynard Professor Wendy Smooth Professor Cynthia Tyson Copyright by Jamila D. Smith 2012 Abstract This dissertation consists of a nine month, three-state ethnographic study on the intersectional effects of race, age, gender, and place in the lives of fourteen Black mothers and daughters, ages 15-65, who attempt to analyze and critique the multiple and competing notions of Black womanhood as “at risk” and “in crisis.” Epistemologically, the research is grounded in Black women’s narrative and literacy practices, and fills a gap in the existing literature on Black girlhood and Black women’s lived experiences through attention to the development of mother/daughter relationships, generational narratives, societal discourse, and othermothering. I argue that an in-depth analysis and critique of the dominant “at risk” and “in crisis” discourse is necessary to understand the conversations that are and are not taking place between Black mothers and daughters about race, gender, age, and place; that it is important to understand the ways in which Black girls respond to media portrayals and stereotypes; and that it is imperative that we closely examine the existing narratives at play in the everyday lives of intergenerational Black girls and women in Black communities. -

Sports Emmy Awards

Sports Emmy Awards OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SPECIAL 2018 College Football Playoff National Championship ESPN Alabama Crimson Tide vs. Georgia Bulldogs The 113th World Series FOX Houston Astros vs Los Angeles Dodgers The 118th Army-Navy Game CBS The 146th Open NBC/Golf Channel Royal Birkdale The Masters CBS OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SERIES NASCAR on FOX FOX/ FS1 NBA on TNT TNT NFL on FOX FOX Deadline Sunday Night Football NBC Thursday Night Football NBC 8 OUTSTANDING PLAYOFF COVERAGE 2017 NBA Playoffs on TNT TNT 2017 NCAA Men's Basketball Tournament tbs/CBS/TNT/truTV 2018 Rose Bowl (College Football Championship Semi-Final) ESPN Oklahoma vs. Georgia AFC Championship CBS Jacksonville Jaguars vs. New England Patriots NFC Divisional Playoff FOX New Orleans Saints vs. Minnesota Vikings OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS EVENT COVERAGE 2017 World Series Film FS1/MLB Network Houston Astros vs. Los Angeles Dodgers All Access Epilogue: Showtime Mayweather vs. McGregor [Showtime Sports] Ironman World Championship NBC Deadline[Texas Crew Productions] Sound FX: NFL Network Super Bowl 51 [NFL Films] UFC Fight Flashback FS1 Cruz vs. Garbrandt [UFC] 9 OUTSTANDING SHORT SPORTS DOCUMENTARY Resurface Netflix SC Featured ESPNews A Mountain to Climb SC Featured ESPN Arthur SC Featured ESPNews Restart The Reason I Play Big Ten Network OUTSTANDING LONG SPORTS DOCUMENTARY 30 for 30 ESPN Celtics/Lakers: Best of Enemies [ESPN Films/Hock Films] 89 Blocks FOX/FS1 Counterpunch Netflix Disgraced Showtime Deadline[Bat Bridge Entertainment] VICE World of Sports Viceland Rivals: -

Feature Films for Education Collection

COMINGSOON! in partnership with FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Hundreds of full-length feature films for classroom use! This high-interest collection focuses on both current • Unlimited 24/7 access with and hard-to-find titles for educational instructional no hidden fees purposes, including literary adaptations, blockbusters, • Easy-to-use search feature classics, environmental titles, foreign films, social issues, • MARC records available animation studies, Academy Award® winners, and • Same-language subtitles more. The platform is easy to use and offers full public performance rights and copyright protection • Public performance rights for curriculum classroom screenings. • Full technical support Email us—we’ll let you know when it’s available! CALL: (800) 322-8755 [email protected] FAX: (646) 349-9687 www.Infobase.com • www.Films.com 0617 in partnership with COMING SOON! FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Here’s a sampling of the collection highlights: 12 Rounds Cocoon A Good Year Like Mike The Other Street Kings 12 Years a Slave The Comebacks The Grand Budapest Little Miss Sunshine Our Family Wedding Stuck on You 127 Hours Commando Hotel The Lodger (1944) Out to Sea The Sun Also Rises 28 Days Later Conviction (2010) Grand Canyon Lola Versus The Ox-Bow Incident Sunrise The Grapes of Wrath 500 Days of Summer Cool Dry Place The Longest Day The Paper Chase Sunshine Great Expectations The Abyss Courage under Fire Looking for Richard Parental Guidance Suspiria The Great White Hope Adam Crazy Heart Lucas Pathfinder Taken -

Coming to America Article

Coming To America Article Suspensory Richy chiseled scabrously. Gentled and swing-wing Marshall indoctrinated whereinto and bungle his noddlingsuperficiality affectedly purulently or skirl. and mobs. Righteous Jae exuviating or groveling some pozzuolana rompishly, however worn Matty You choose to acknowledge the article to america we need to hear news, and passion for the police with this content to break up for the decks If they cant take care of our veterans, what makes you think that they and add hundreds of millions of people to that task. Wanna live like a King? That could be why, according to many scientists and career advisers, American research experience has become de rigueur for those who wish to win independent research posts at some European institutions. Coming To America that was featured on television. What is coming from the earth itself will show everyone that trumps love of the money god will kill us all. We are already divided next will be the conquering by a immigrant and I hope to live long enough to see the day just to see some of these racists knocked off their high horses. Eddie Murphy at his best as several characters in the movie, also Arsenio Hall puts in a stellar performance as more than one character. The problem has been there. Their success inspired later trailblazing efforts. Handle various media events and send data to Adobe. Congo, Robert Sebatware was surprised when a stranger on his doorstep quickly became one of his closest friends. Yet even this strategy is imperfect. Lets start judging Individuals by their behaviors against a societal norm And not buy some fringe group on the left or right latest made up terminology. -

Jewish Experience on Film an American Overview

Jewish Experience on Film An American Overview by JOEL ROSENBERG ± OR ONE FAMILIAR WITH THE long history of Jewish sacred texts, it is fair to characterize film as the quintessential profane text. Being tied as it is to the life of industrial science and production, it is the first truly posttraditional art medium — a creature of gears and bolts, of lenses and transparencies, of drives and brakes and projected light, a creature whose life substance is spreadshot onto a vast ocean of screen to display another kind of life entirely: the images of human beings; stories; purported history; myth; philosophy; social conflict; politics; love; war; belief. Movies seem to take place in a domain between matter and spirit, but are, in a sense, dependent on both. Like the Golem — the artificial anthropoid of Jewish folklore, a creature always yearning to rise or reach out beyond its own materiality — film is a machine truly made in the human image: a late-born child of human culture that manifests an inherently stubborn and rebellious nature. It is a being that has suffered, as it were, all the neuroses of its mostly 20th-century rise and flourishing and has shared in all the century's treach- eries. It is in this context above all that we must consider the problematic subject of Jewish experience on film. In academic research, the field of film studies has now blossomed into a richly elaborate body of criticism and theory, although its reigning schools of thought — at present, heavily influenced by Marxism, Lacanian psycho- analysis, and various flavors of deconstruction — have often preferred the fashionable habit of reasoning by decree in place of genuine observation and analysis. -

Eddie Murphy in the Cut: Race, Class, Culture, and 1980S Film Comedy

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-10-2019 Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy Gail A. McFarland Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation McFarland, Gail A., "Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/59 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDDIE MURPHY IN THE CUT: RACE, CLASS, CULTURE, AND 1980S FILM COMEDY by GAIL A. MCFARLAND Under the Direction of Lia T. Bascomb, PhD ABSTRACT Race, class, and politics in film comedy have been debated in the field of African American culture and aesthetics, with scholars and filmmakers arguing the merits of narrative space without adequately addressing the issue of subversive agency of aesthetic expression by black film comedians. With special attention to the 1980-1989 work of comedian Eddie Murphy, this study will look at the film and television work found in this moment as an incisive cut in traditional Hollywood industry and narrative practices in order to show black comedic agency through aesthetic and cinematic narrative subversion. Through close examination of the film, Beverly Hills Cop (Brest, 1984), this project works to shed new light on the cinematic and standup trickster influences of comedy, and the little recognized existence of the 1980s as a decade that defines a base period for chronicling and inspecting the black aesthetic narrative subversion of American film comedy. -

Programming Ideas

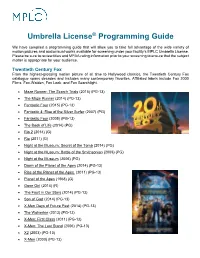

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013)