Pangaea 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Art Magazine Issue # Sixteen December | January Twothousandnine Spedizione in A.P

contemporary art magazine issue # sixteen december | january twothousandnine Spedizione in a.p. -70% _ DCB Milano NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 KAREN KILIMNIK NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 WadeGUYTON BLURRY CatherineSULLIVAN in collaboration with Sean Griffin, Dylan Skybrook and Kunle Afolayan Triangle of Need VibekeTANDBERG The hamburger turns in my stomach and I throw up on you. RENOIR Liquid hamburger. Then I hit you. After that we are both out of words. January - February 2009 DEBUSSY URS FISCHER GALERIE EVA PRESENHUBER WWW.PRESENHUBER.COM TEL: +41 (0) 43 444 70 50 / FAX: +41 (0) 43 444 70 60 LIMMATSTRASSE 270, P.O.BOX 1517, CH–8031 ZURICH GALLERY HOURS: TUE-FR 12-6, SA 11-5 DOUG AITKEN, EMMANUELLE ANTILLE, MONIKA BAER, MARTIN BOYCE, ANGELA BULLOCH, VALENTIN CARRON, VERNE DAWSON, TRISHA DONNELLY, MARIA EICHHORN, URS FISCHER, PETER FISCHLI/DAVID WEISS, SYLVIE FLEURY, LIAM GILLICK, DOUGLAS GORDON, MARK HANDFORTH, CANDIDA HÖFER, KAREN KILIMNIK, ANDREW LORD, HUGO MARKL, RICHARD PRINCE, GERWALD ROCKENSCHAUB, TIM ROLLINS AND K.O.S., UGO RONDINONE, DIETER ROTH, EVA ROTHSCHILD, JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC SCHNYDER, STEVEN SHEARER, JOSH SMITH, BEAT STREULI, FRANZ WEST, SUE WILLIAMS DOUBLESTANDARDS.NET 1012_MOUSSE_AD_Dec2008.indd 1 28.11.2008 16:55:12 Uhr Galleria Emi Fontana MICHAEL SMITH Viale Bligny 42 20136 Milano Opening 17 January 2009 T. +39 0258322237 18 January - 28 February F. +39 0258306855 [email protected] www.galleriaemifontana.com Photo General Idea, 1981 David Lamelas, The Violent Tapes of 1975, 1975 - courtesy: Galerie Kienzie & GmpH, Berlin L’allarme è generale. Iper e sovraproduzione, scialo e vacche grasse si sono tra- sformati di colpo in inflazione, deflazione e stagflazione. -

Clifton Chronicle

SUMMER 2012 Volume Twenty-Two Number One CA Publicationlifton of Clifton Town Meeting C You Dohronicle It You Write It We Print It Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 Box 20067 P.O. Clifton Chronicle Clifton Home Composite—You will not be touring this home any time soon, made up of the homes on Evanswood Place by Bruce Ryan, former resident and producer of yearly Evanswood block party invitation where this illustration first appeared. Clifton House Tour this Mother’s Day By Eric Clark Every third year on Mother’s are like stepping back in time to the sored them throughout the ‘70s and Day, a group of Clifton homeowners period in which they were built. ‘80s, taking a hiatus between 1988 open their doors to greater Cincinnati Although we do not disclose and 1997. Since the resumption and say, “Come on in and have a look pictures or the addresses of the of the tours, the event has drawn around!” So, mark your calendars for homes until the day of the tour. We people from all over Cincinnati and Mother’s Day, May 13, 2012. are confident that if you have an ap- has been a great way to spend part Clifton Town Meeting has lined preciation for architecture or interior of Mother’s Day. up some great houses for the 2012 design, or if you just enjoy touring Tickets are $17.50 in advance tour and it includes something for beautiful Clifton homes, you will and $22.50 the day of the tour. Tick- everyone with a wide and eclectic NOT be disappointed. -

Francis Bacon Contents: of Truth of Death of Unity in Religion Of

THE ESSAYS (published 1601) Francis Bacon Contents: Of Truth Of Death Of Unity in Religion Of Revenge Of Adversity Of Simulation and Dissimulation Of Parents and Children Of Marriage and Single Life Of Envy Of Love Of Great Place Of Boldness Of Goodness and Goodness of Nature Of Nobility Of Seditions and Troubles Of Atheism Of Superstition Of Travel Of Empire Of Counsel Of Delays Of Cunning Of Wisdom for a Man's Self Of Innovations Of Dispatch Of Seeming Wise Of Friendship Of Expense Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates Of Regiment of Health Of Suspicion Of Discourse Of Plantations Of Riches Of Prophecies Of Ambition Of Masques and Triumphs Of Nature in Men Of Custom and Education Of Fortune Of Usury Of Youth and Age Of Beauty Of Deformity Of Building Of Gardens Of Negotiating Of Followers and Friends Of Suitors Of Studies Of Faction Of Ceremonies and Respects Of Praise Of Vain-glory Of Honor and Reputation Of Judicature Of Anger Of Vicissitude of Things Of Fame Of Truth WHAT is truth? said jesting Pilate,and would not stay for an answer. Certainly there be, that delight in giddiness, and count it a bondage to fix a belief; affecting free-will in thinking, as well as in acting. And though the sects of philosophers of that kind be gone, yet there remain certain dis- coursing wits, which are of the same veins, though there be not so much blood in them, as was in those of the ancients. But it is not only the difficulty and labor, which men take in finding out of truth, nor again, that when it is found, it imposeth upon men's thoughts, that doth bring lies in favor; but a natural, though corrupt love, of the lie itself. -

Acta 15 Pass

00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 1 CATHOLIC SOCIAL DOCTRINE AND HUMAN RIGHTS 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 2 Address The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences Casina Pio IV, 00120 Vatican City Tel.: +39 0669881441 – Fax: +39 0669885218 E-mail: [email protected] 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 3 THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Acta 15 CATHOLIC SOCIAL DOCTRINE AND HUMAN RIGHTS the PROCEEDINGS of the 15th Plenary Session 1-5 May 2009 • Casina Pio IV Edited by Roland Minnerath Ombretta Fumagalli Carulli Vittorio Possenti IA SCIEN M T E IA D R A V C M A S A O I C C I I A F I L T I V N M O P VATICAN CITY 2010 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 4 The opinions expressed with absolute freedom during the presentation of the papers of this plenary session, although published by the Academy, represent only the points of view of the participants and not those of the Academy. 978-88-86726-25-2 © Copyright 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, photocopying or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES VATICAN CITY 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 5 His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 6 Participants in the conference hall of the Casina Pio IV 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 7 Participants of the 15th Plenary Session 00_Prima Parte_Acta15:PrimaParte-Acta917/02/1008:35Pagina8 His Holiness Benedict XVI with the Participants of the 15th Plenary Session 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 9 CONTENTS Address of the Holy Father to the Participants......................................... -

Bayeté CV 2013

Bayeté Ross Smith (+1) 917 721 8899 bayeterosssmith.com 766 St. Nicholas avenue #3B, New York, NY 10031 EDUCATION M.F.A. 2004 Photography California College of the Arts B.S. 1999 Photography Florida A & M University AWARDS AND GRANTS 2013 A Blade of Grass Fellowship – A Blade of Grass, New York, NY 2011 FSP Jerome Fellowship – Franconia Sculpture Park, Franconia, MN 2010 Create Change Artist-In-Residence – The Laundromat Project, New York, NY 2008 McColl Center Artist-In-Residence – McColl Center for Visual Art, Charlotte, NC 2008 Kala Fellowship – Kala Art Institute, Berkeley CA 2008 Can Serrat International Art Center, Barcelona, Spain 2006 LEF Foundation, Supplemental Grant for Along the Way (Cause Collective) 2004 Southern Exposure – San Francisco, CA Resident Artist, Mission Voices SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Got The Power: Birmingham, Alabama School of Fine Art, Birmingham AL 2012 Question Bridge: Black Males, The Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn NY, The Oakland Museum of California, The Salt Lake City art Center, Salt Lake City UT, Project Row Houses, Houston TX. Question Bridge is collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas, Chris Johnson and Kamal Sinclair Gatling (America): Portraits of Gun Ownership, Beta Pictoris Gallery, Birmingham, Al Bayeté Ross Smith: Mirrors, California Institute for Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA 2010 Bayeté Ross Smith: Our Kind Of People, Beta Pictoris Gallery, Birmingham, Al Bayeté Ross Smith: Passing II, The Halls at Bowling Green, City College, New York, NY 2008 Pomp and Circumstance: First Time To Be Adults, Patricia Sweetow Gallery, S.F., CA 2007 Passing, Bluespace Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2003 Upwardly Mobile, The Richmond Art Center, Richmond, CA SCREENINGS 2012 Sundance Film Festival: New Frontier Category, Salt Lake City UT – Question Bridge: Black Males 2012 Sheffield Doc Fest, Sheffield, England - Question Bridge: Black Males 2012 L.A. -

Memories for a Blessing Jewish Mourning Rituals and Commemorative Practices in Postwar Belarus and Ukraine, 1944-1991

Memories for a Blessing Jewish Mourning Rituals and Commemorative Practices in Postwar Belarus and Ukraine, 1944-1991 by Sarah Garibov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ronald Suny, Co-Chair Professor Jeffrey Veidlinger, Co-Chair Emeritus Professor Todd Endelman Professor Zvi Gitelman Sarah Garibov [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5417-6616 © Sarah Garibov 2017 DEDICATION To Grandma Grace (z”l), who took unbounded joy in the adventures and accomplishments of her grandchildren. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I am forever indebted to my remarkable committee. The faculty labor involved in producing a single graduate is something I have never taken for granted, and I am extremely fortunate to have had a committee of outstanding academics and genuine mentshn. Jeffrey Veidlinger, thank you for arriving at Michigan at the perfect moment and for taking me on mid-degree. From the beginning, you have offered me a winning balance of autonomy and accountability. I appreciate your generous feedback on my drafts and your guidance on everything from fellowships to career development. Ronald Suny, thank you for always being a shining light of positivity and for contributing your profound insight at all the right moments. Todd Endelman, thank you for guiding me through modern Jewish history prelims with generosity and rigor. You were the first to embrace this dissertation project, and you have faithfully encouraged me throughout the writing process. Zvi Gitelman, where would I be without your wit and seykhl? Thank you for shepherding me through several tumultuous years and for remaining a steadfast mentor and ally. -

A Body of Divinity by Thomas Watson (PDF)

A Body of Divinity by Thomas Watson A Body of Divinity Thomas Watson Table of Contents About This Book...................................... p. ii A Body of Divinity ..................................... p. 1 Contents ........................................... p. 2 Brief Memoir Of Thomas Watson ........................... p. 4 1. A Preliminary Discourse To Catechising .................... p. 9 2. Introduction ....................................... p. 13 1. Man's Chief End ................................... p. 13 2. The Scriptures .................................... p. 26 3. God and his creation ................................. p. 35 1. The Being Of God .................................. p. 35 2. The Knowledge Of God .............................. p. 45 3. The Eternity Of God ................................. p. 49 4. The Unchangeableness Of God ......................... p. 53 5. The Wisdom Of God ................................ p. 57 6. The Power Of God ................................. p. 61 7. The Holiness Of God ................................ p. 64 8. The Justice Of God ................................. p. 68 9. The Mercy Of God .................................. p. 72 10. The Truth Of God ................................. p. 76 11. The Unity Of God ................................. p. 79 12. The Trinity ...................................... p. 82 13. The Creation .................................... p. 85 14. The Providence Of God ............................. p. 89 4. The fall .......................................... p. -

Annual Community Holocaust Memorial Service He Annual Community Holo- Dr

www.JewishFederationLCC.org Vol. 39, No. 10 n June 2017 / 5777 Annual Community Holocaust Memorial Service he annual Community Holo- Dr. Paul Bartrop, a knowledgeable caust Memorial Service was and respected Holocaust scholar; both Theld on Sunday, April 23 at Jewish and non-Jewish clergy; and lay Temple Beth El. Over 250 people leaders representing their organiza- turned out to recall the victims of the tions. Holocaust, to honor those who sur- The most poignant part of every vived and those who saved them, and Holocaust remembrance is the lighting to help fill our obligation “to remember of the memorial candles by those who and not to forget.” survived the Holocaust. We are blessed Participants in the very moving to have them in our community and service included: Rafael Ruiz, a tal- that they are here to remind future gen- Rabbi Marc Sack of Temple Judea Guest speaker Dr. Paul Bartrop, Director of the ented 16-year-old violinist; pianist and erations of not only remembering the Center for Judaic, Holocaust, and Genocide longtime Jewish community mem- past, but of the importance of building Studies at Florida Gulf Coast University, ber Randy Kashi; an interfaith choir; a safe, more humane world. speaks about “Music and the Holocaust” Rabbi Nicole Luna of Temple Beth El Dr. Paul Bartrop addresses community members who gathered in the Members of the Jewish community and Unitarian Universalist Church, led Temple Beth El sanctuary to remember the victims of the Holocaust by choir director Suellen Kipp, sing music from the Holocaust Rabbi -

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

FOXE'S BOOK OF MARTYRS CHAPTER I - History of Christian Martyrs to the First General Persecutions Under Nero Christ our Savior, in the Gospel of St. Matthew, hearing the confession of Simon Peter, who, first of all other, openly acknowledged Him to be the Son of God, and perceiving the secret hand of His Father therein, called him (alluding to his name) a rock, upon which rock He would build His Church so strong that the gates of hell should not prevail against it. In which words three things are to be noted: First, that Christ will have a Church in this world. Secondly, that the same Church should mightily be impugned, not only by the world, but also by the uttermost strength and powers of all hell. And, thirdly, that the same Church, notwithstanding the uttermost of the devil and all his malice, should continue. Which prophecy of Christ we see wonderfully to be verified, insomuch that the whole course of the Church to this day may seem nothing else but a verifying of the said prophecy. First, that Christ hath set up a Church, needeth no declaration. Secondly, what force of princes, kings, monarchs, governors, and rulers of this world, with their subjects, publicly and privately, with all their strength and cunning, have bent themselves against this Church! And, thirdly, how the said Church, all this notwithstanding, hath yet endured and holden its own! What storms and tempests it hath overpast, wondrous it is to behold: for the more evident declaration whereof, I have addressed this present history, to the end, first, that the wonderful works of God in His Church might appear to His glory; also that, the continuance and proceedings of the Church, from time to time, being set forth, more knowledge and experience may redound thereby, to the profit of the reader and edification of Christian faith. -

2012–13 Annual Report (PDF)

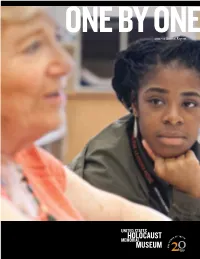

ONE BY ONE2012–13 Annual Report With the survivors at our side, Leadership Message 4 Rescuing the Evidence 8 for two decades this sacred Advancing New Knowledge 10 place has challenged leaders Educating New Generations 12 Preventing Genocide 14 and citizens, teachers and The Power of Our Partnership 16 students—one by one—to 20th Anniversary National Tribute 18 International Travel Program 22 look inside themselves, Campaign Leadership Giving 24 to look beyond themselves, Donors 26 Financial Statements 46 and to wrestle with some of United States Holocaust Memorial Council 47 the most central issues of human behavior in modern society. So to the question: Does memory have the power to change the world? 20 years on, our answer is a resounding YES. —Sara J. Bloomfield, Director 39 million 90,000 446 50,000 10% 143,000 Since 1993, 39 million people More than 80,000 national Representing diverse Over 50,000 educators—from Our website ushmm.org— Inspired by the Museum’s have had an in-person encounter and local law enforcement academic disciplines, 446 those at the beginning of their now available in 15 languages contemporary genocide with our most important message: professionals and 10,000 scholars from 30 countries careers to the most advanced— including Arabic, Chinese, Farsi, installation FROM MEMORY The Holocaust could have been members of the US court have completed resident have been trained by the Russian, Spanish, Turkish, and TO ACTION: MEETING THE prevented. Over 35 million people system have participated in fellowships at the Museum’s Museum in the most effective Urdu—has become the leading CHALLENGE OF GENOCIDE, have visited the Museum on the Museum training programs, Center for Advanced ways to teach this history. -

Claire Lieberman Artistic Arctic Ambassador

APRIL 2014 The ofcial news magazine serving Claire Lieberman Artistic Arctic Ambassador Holiday Garbage/Recycling Changes: Good Friday collection for residents who normally get their trash and recycling picked up on Friday (April 18th) will have it picked up on Thursday, April 17th. Photo by: Boutique Photographer Linda Gumieny Let us help you get the protection you need. Call us today for affordable home & auto coverage. We can help you save twice when you bring both your home and auto policies to Allstate. Insure the car McCabe Agency (414) 961-1166 and save money 4010 N. Oakland Ave. on the garage. Shorewood, WI 53211 [email protected] Call or stop by for a free quote. Subject to terms, conditions, qualifications and availability. Allstate Property and Casualty Insurance Company: Northbrook, IL. © 2012 Allstate Insurance Company. 67533 SIMPLEXITY [SIMPLICITY & COMPLEXITY] Selling a home is simple… and complex. Five basic principles executed precisely work — every time. The challenge isn’t knowing the principles. It’s knowing how to execute them flawlessly that can make the difference in how fast a home sells and how much money you make. Doing the right things well is what I do 414.350.4611 best. Let’s work together to get [email protected] your home sold. essam.shorewest.com EHO APRIL 2014 2 BestVersionMedia.com BAY LEavES “Bringing Neighbors Together” PUBLISHERS: Dear Residents, Christa Banholzer and Kathy Durand We celebrate Earth Day on April 22nd, but why not support Earth Day all year long by shopping locally? Check out the WFB Business Improvement District article to learn how shopping locally can support the community while also helping the environment. -

Faculty Pursue Exclusive Residencies

Founded in 1882, The Cleveland Institute of Art is an independent college of art and design committed to leadership and vision in all forms of visual arts education. The Institute makes enduring contributions to art and education and connects to the community through gallery exhibitions, lectures, a continuing education pro- Link gram and The Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque. FALL 2009 NEWS FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF THE CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART RIGHT: Professor Petra Soesemann ’77 at worK in her Roswell, NM studio. BELOW: Detail from Soesemann’S recent worK. FROM FRANCE Summer OFFERS CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART FACULTY MEMBERS A BREAK FROM TEACHING AND TIME TO CONCENTRATE ON THEIR PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE AND SCHOLARSHIP. THIS PAST SUMMER, NINE FACULTY MEMBERS TOOK IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL. THEY WERE CHOSEN TO BANFF: FROM AMONG HUNDREDS OF APPLICANTS FOR RESIDENCIES AT ART CENTERS ACROSS NORTH AMERICA AND ABROAD WHERE THEY HAD THE nLUXURIES OF TIME AND SPACE TO THINK, READ, CREATE, COLLABORATE WITH PEERS AND GROW PROFESSIONALLY. SOME RESIDENCIES OFFERED THE STIMULATION OF A COMMUITY OF ARTISTS; OTHERS OFFERED SILENCE. SOME PROVIDED FULLY EQUIPPED STUDIOS; ONE A QUIET OLD FACULTY PURSUE LIBRARY WITH WIRELESS ACCESS. AS DIVERSE AS THESE EXPERIENCES WERE, ALL REPRESENTED ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF PROFESSIONAL SUCCESS AND EXPOSURE TO NEW IDEAS FOR FACULTY MEMBERS TO SHARE WITH INSTITUTE STUDENTS. EXCLUSIVE TIME FOR EXPERIMENTATION Jacques Derrida. “Banff has made pos- her to branch out into new sculptural sible this depth of exploration and materials. And in between, she com- As her six-week residency came to a RESIDENCIES experimentation through the facilities pleted a workspace residency at Dieu close at The Banff Centre in Alberta, and support it offers.” Donne Papermill in New York City, Canada, Assistant Professor Lane Having the time, space and encour- which consisted of seven days in this Cooper said her experience there had agement to experiment is one of the studio over the course of a year.