Interview with Jessica Utts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Annual Report

Contents Clay Mathematics Institute 2006 James A. Carlson Letter from the President 2 Recognizing Achievement Fields Medal Winner Terence Tao 3 Persi Diaconis Mathematics & Magic Tricks 4 Annual Meeting Clay Lectures at Cambridge University 6 Researchers, Workshops & Conferences Summary of 2006 Research Activities 8 Profile Interview with Research Fellow Ben Green 10 Davar Khoshnevisan Normal Numbers are Normal 15 Feature Article CMI—Göttingen Library Project: 16 Eugene Chislenko The Felix Klein Protocols Digitized The Klein Protokolle 18 Summer School Arithmetic Geometry at the Mathematisches Institut, Göttingen, Germany 22 Program Overview The Ross Program at Ohio State University 24 PROMYS at Boston University Institute News Awards & Honors 26 Deadlines Nominations, Proposals and Applications 32 Publications Selected Articles by Research Fellows 33 Books & Videos Activities 2007 Institute Calendar 36 2006 Another major change this year concerns the editorial board for the Clay Mathematics Institute Monograph Series, published jointly with the American Mathematical Society. Simon Donaldson and Andrew Wiles will serve as editors-in-chief, while I will serve as managing editor. Associate editors are Brian Conrad, Ingrid Daubechies, Charles Fefferman, János Kollár, Andrei Okounkov, David Morrison, Cliff Taubes, Peter Ozsváth, and Karen Smith. The Monograph Series publishes Letter from the president selected expositions of recent developments, both in emerging areas and in older subjects transformed by new insights or unifying ideas. The next volume in the series will be Ricci Flow and the Poincaré Conjecture, by John Morgan and Gang Tian. Their book will appear in the summer of 2007. In related publishing news, the Institute has had the complete record of the Göttingen seminars of Felix Klein, 1872–1912, digitized and made available on James Carlson. -

Statistical Problems Involving Permutations with Restricted Positions

STATISTICAL PROBLEMS INVOLVING PERMUTATIONS WITH RESTRICTED POSITIONS PERSI DIACONIS, RONALD GRAHAM AND SUSAN P. HOLMES Stanford University, University of California and ATT, Stanford University and INRA-Biornetrie The rich world of permutation tests can be supplemented by a variety of applications where only some permutations are permitted. We consider two examples: testing in- dependence with truncated data and testing extra-sensory perception with feedback. We review relevant literature on permanents, rook polynomials and complexity. The statistical applications call for new limit theorems. We prove a few of these and offer an approach to the rest via Stein's method. Tools from the proof of van der Waerden's permanent conjecture are applied to prove a natural monotonicity conjecture. AMS subject classiήcations: 62G09, 62G10. Keywords and phrases: Permanents, rook polynomials, complexity, statistical test, Stein's method. 1 Introduction Definitive work on permutation testing by Willem van Zwet, his students and collaborators, has given us a rich collection of tools for probability and statistics. We have come upon a series of variations where randomization naturally takes place over a subset of all permutations. The present paper gives two examples of sets of permutations defined by restricting positions. Throughout, a permutation π is represented in two-line notation 1 2 3 ... n π(l) π(2) π(3) ••• τr(n) with π(i) referred to as the label at position i. The restrictions are specified by a zero-one matrix Aij of dimension n with Aij equal to one if and only if label j is permitted in position i. Let SA be the set of all permitted permutations. -

PERSI DIACONIS (650) 725-1965 Mary V

PERSI DIACONIS (650) 725-1965 Mary V. Sunseri Professor [email protected] http://statistics.stanford.edu/persi-diaconis Professor of Statistics Sequoia Hall, 390 Jane Stanford Way, Room 131 Sloan Mathematics Center, 450 Jane Stanford Way, Room 106 Professor of Mathematics Stanford, California 94305 Professional Education College of the City of New York B.S. Mathematics 1971 Harvard University M.A. Mathematical Statistics 1972 Harvard University Ph.D. Mathematical Statistics 1974 Administrative Appointments 2006–2007 Visiting Professor, Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis 1999–2000 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences 1998– Professor of Mathematics, Stanford University 1998– Mary Sunseri Professor of Statistics, Stanford University 1996–1998 David Duncan Professor, Department of Mathematics and ORIE, Cornell University 1987–1997 George Vasmer Leverett Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University 1985–1986 Visiting Professor, Department of Mathematics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1985–1986 Visiting Professor, Department of Mathematics, Harvard University 1981–1987 Professor of Statistics, Stanford University 1981–1982 Visiting Professor, Department of Statistics, Harvard University 1979–1980 Associate Professor of Statistics, Stanford University 1978–1979 Research Staff Member, AT&T Bell Laboratories 1974–1979 Assistant Professor of Statistics, Stanford University Professional Activities 1972–1980 Statistical Consultant, Scientific American 1974– Statistical Consultant, Bell Telephone Laboratories -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

802 Transcript

"BEYOND SCIENCE?" SHOW 802 Teaser Episode Open Water, Water Everywhere Aliens Have Landed New Energy Age Paper Personality Healing Touch TEASER ALAN ALDA I'd like you to meet a new acquaintance of mine. Some people think he, or she, or it, just recently arrived from outer space. Others aren't so sure. On this edition of Scientific American Frontiers, we're going to try to find out what's real in science, and what's not. ALAN ALDA (Narration) We'll ask if balancing a patient's energy pattern can lead to healing. We'll challenge dowsers to find water, and to try our rigorous test. We'll see if, by putting pen to paper, we give ourselves away. And we'll look for zero point energy -- is it real, or is it a dream? ALAN ALDA I'm Alan Alda, join me now as we venture into the realm of pseudoscience. back to top INTRO ALAN ALDA (Narration) We've asked DIANNA PAZ to visit a palm reader. She doesn't know it, but the reader -- who's a University of Oregon psychology professor -- says palm reading is pure fiction. And Dianna doesn't believe in it herself. But something strange is about to happen -- Dianna's going to become a believer. RAY HYMAN You have a hard time hanging onto money. You have spaces between your fingers and... ALAN ALDA (Narration) Ray Hyman gently raises common topics, like money or career, on the lookout for give-away responses -- a nod here, or a word there. RAY HYMAN .. -

Issue-05-9.Pdf

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist. -

Augustine Responds to the Editor

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 235 Augustine Responds To the Editor: Having presented a comprehensive three-part critique of survival- ist interpretations of near-death experiences (NDEs) and defended it against multiple commentators, I am generally inclined to allow readers of this Journal to reflect upon the entire exchange and take from it what they will without offering further comment. However, I feel compelled to point out a number of fallacies that Neal Grossman commits when, ironically, accusing me of fallacious reasoning. Although Grossman prefaces his letter with the disclaimer that it "will not be a response to anything [I] wrote," he explicitly implicates me along with "other debunkers" in customarily employing fallacious reasoning, and in any case there is no point in him bringing up errors "that Augustine and his fellow materialist ideologues frequently commit" if he does not mean to imply that my critique contains them. 236 JOURNAL OF NEAR-DEATH STUDIES Right from the start, Grossman stereotypes those skeptical of survivalist interpretations of NDEs as ideologues plagued by "unwa- vering certainty" in a materialist faith. But his comments reveal his own "unwavering certainty" that NDEs and other phenomena represent a smoking-gun falsification of materialism. One wonders if any evidence could ever persuade Grossman of the truth of strict materialism or a related view, such as David Chalmers's property dualism, in which mental states are nonphysical properties of the physical brain and thus irreducible to brain states, but existentially dependent upon the properly functioning brain in which they inhere (Chalmers, 1996). Indeed, one wonders if Grossman thinks that it is possible for anyone to hold a materialist or similar position rationally on the basis of the empirical evidence. -

Five Stories for Richard

Unspecified Book Proceedings Series Five Stories for Richard Persi Diaconis Richard Stanley writes with a clarity and originality that makes those of us in his orbit happy we can appreciate and apply his mathematics. One thing missing (for me) is the stories that gave rise to his questions, the stories that relate his discoveries to the rest of mathematics and its applications. I mostly work on problems that start in an application. Here is an example, leading to my favorite story about stories. In studying the optimal strategy in a game, I needed many random permutations of 52 cards. The usual method of choosing a permutation on the computer starts with n things in order, then one picks a random number from 1 to n | say 17 | and transposes 1 and 17. Next one picks a random number from 2 to n and transposes these, and so forth, finishing with a random number from n − 1 to n. This generates all n! permutations uniformly. When our simulations were done (comprising many hours of CPU time on a big machine), the numbers \looked funny." Something was wrong. After two days of checking thousands of lines of code, I asked \How did you choose the permutations?" The programmer said, \Oh yes, you told me that fussy thing, `random with 1, etc' but I made it more random, with 100 transpositions of (i; j); 1 ≤ i; j ≤ n." I asked for the work to be rerun. She went to her boss and to her boss' boss who each told me, essentially, \You mathematicians are crazy; 100 random transpositions has to be enough to mix up 52 cards." So, I really wanted to know the answer to the question of how many transpositions will randomize 52 cards. -

Palmistry: Science Or Hand-Jive?

the Skeptical Inquirer PALMISTRY: SCIENCE OR HAND-JIVE? SRI GELLER TEST / LOCHNESS TREE TRUNK / A PILOT'S UFO WHY SKEPTICS ARE SKEPTICAL VOL. VII No. 2 WINTER 191 Published by the Committee lor the Scientific Investigation of :of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell. Martin Gardner. Ray Hyman. Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge. John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher. John R. Cole. Richard de Mille, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp. James Oberg. Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Production Editor Belsy Offermann. Business Manager Lynette Nisbet. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Idelle Abrams. Judy Hays. Alfreda Pidgeon Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abed, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist. SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer. Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher. Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., O.K.: Kendrick Frazier, science writer. Editor. THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. Secretary, I'Union Rationaliste; Martin Gardner, author. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Professor of Magic Mathematics Author(S): DON ALBERS and Persi Diaconis Source: Math Horizons, Vol

Professor of Magic Mathematics Author(s): DON ALBERS and Persi Diaconis Source: Math Horizons, Vol. 2, No. 3 (February 1995), pp. 11-15 Published by: Mathematical Association of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25678003 . Accessed: 30/10/2014 13:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Mathematical Association of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Math Horizons. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.10.72.232 on Thu, 30 Oct 2014 13:17:17 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions DONALBERS Professor of-Maaie Mathematics more more Persi Diaconis, professor ofmath just gets and random. That A Magical Beginning a ematics at Harvard, has just is not the way it works at all. It is ALBERS: At theage 14, you leftyour turned 50, but the energy and theorem that this phenomenon of the of next ten intact as New York City home and spent the of the 14-year old Persi who order of cards being you go intensity on What . to years the road practicing magic. left high school to do magic full time from one, two, three shuffles. -

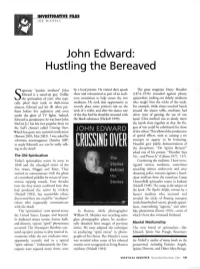

John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved

INVESTIGATIVE FILES JOE NICKELL John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved uperstar "psychic medium" John by a local printer. He visited dieir spook The great magician Harry Houdini Edward is a stand-up guy. Unlike show and volunteered as part of an audi- (1874—1926) crusaded against phony the spiritualists of yore, who typi- ence committee to help secure the two spiritualists, seeking out elderly mediums S mediums. He took that opportunity to who taught him the tricks of die trade. cally plied their trade in dark-room seances, Edward and his ilk often per- secretly place some printer's ink on the For example, while sitters touched hands form before live audiences and even neck of a violin, and after the seance one around die seance table, mediums had under the glare of TV lights. Indeed, of the duo had his shoulder smeared with clever ways of gaining die use of one Edward (a pseudonym: he was born John the black substance (Nickell 1999). hand. (One method was to slowly move MaGee Jr.) has his own popular show on the hands close togedier so diat die fin- die SciFi channel called Crossing Over, gers of one could be substituted for those "which has gone into national syndication JOHN EDWARD of die other.) This allowed die production (Barrett 2001; Mui 2001). I was asked by of special effects, such as causing a tin television newsmagazine Dateline NBC trumpet to appear to be levitating. to study Edward's act: was he really talk- Houdini gave public demonstrations of ing to the dead? HI the deceptions.