Dimensions of Continents and Oceans – Water Has Carved a Perfect Cistern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERIOR of the EARTH / an El/EMEI^TARY Xdescrrpntion

N \ N I 1i/ / ' /' \ \ 1/ / / s v N N I ' / ' f , / X GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 / N X \ i INTERIOR OF THE EARTH / AN El/EMEI^TARY xDESCRrPNTION The Interior of the Earth An Elementary Description By Eugene C. Robertson GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 Washington 1966 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary Geological Survey H. William Menard, Director First printing 1966 Second printing 1967 Third printing 1969 Fourth printing 1970 Fifth printing 1972 Sixth printing 1976 Seventh printing 1980 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract ......................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... 1 Surface observations .............................................. 1 Openings underground in various rocks .......................... 2 Diamond pipes and salt domes .................................. 3 The crust ............................................... f ........ 4 Earthquakes and the earth's crust ............................... 4 Oceanic and continental crust .................................. 5 The mantle ...................................................... 7 The core ......................................................... 8 Earth and moon .................................................. 9 Questions and answers ............................................. 9 Suggested reading ................................................ 10 ILLUSTRATIONS -

Tectonics and Crustal Evolution

Tectonics and crustal evolution Chris J. Hawkesworth, Department of Earth Sciences, University peaks and troughs of ages. Much of it has focused discussion on of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, the extent to which the generation and evolution of Earth’s crust is UK; and Department of Earth Sciences, University of St. Andrews, driven by deep-seated processes, such as mantle plumes, or is North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK, c.j.hawkesworth@bristol primarily in response to plate tectonic processes that dominate at .ac.uk; Peter A. Cawood, Department of Earth Sciences, University relatively shallow levels. of St. Andrews, North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK; and Bruno The cyclical nature of the geological record has been recog- Dhuime, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills nized since James Hutton noted in the eighteenth century that Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK even the oldest rocks are made up of “materials furnished from the ruins of former continents” (Hutton, 1785). The history of ABSTRACT the continental crust, at least since the end of the Archean, is marked by geological cycles that on different scales include those The continental crust is the archive of Earth’s history. Its rock shaped by individual mountain building events, and by the units record events that are heterogeneous in time with distinctive cyclic development and dispersal of supercontinents in response peaks and troughs of ages for igneous crystallization, metamor- to plate tectonics (Nance et al., 2014, and references therein). phism, continental margins, and mineralization. This temporal Successive cycles may have different features, reflecting in part distribution is argued largely to reflect the different preservation the cooling of the earth and the changing nature of the litho- potential of rocks generated in different tectonic settings, rather sphere. -

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data Walter D. Mooney US Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, USA Claus Prodehl University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Nina I. Pavlenkova RAS Institute of the Physics of the Earth, Moscow, Russia 1. Introduction Year Authors Areas covered J/A/B a The purpose of this chapter is to provide a summary of the seismic velocity structure of the continental lithosphere, 1971 Heacock N-America B 1973 Meissner World J i.e., the crust and uppermost mantle. We define the crust as 1973 Mueller World B the outer layer of the Earth that is separated from the under- 1975 Makris E-Africa, Iceland A lying mantle by the Mohorovi6i6 discontinuity (Moho). We 1977 Bamford and Prodehl Europe, N-America J adopted the usual convention of defining the seismic Moho 1977 Heacock Europe, N-America B as the level in the Earth where the seismic compressional- 1977 Mueller Europe, N-America A 1977 Prodehl Europe, N-America A wave (P-wave) velocity increases rapidly or gradually to 1978 Mueller World A a value greater than or equal to 7.6 km sec -1 (Steinhart, 1967), 1980 Zverev and Kosminskaya Europe, Asia B defined in the data by the so-called "Pn" phase (P-normal). 1982 Soller et al. World J Here we use the term uppermost mantle to refer to the 50- 1984 Prodehl World A 200+ km thick lithospheric mantle that forms the root of the 1986 Meissner Continents B 1987 Orcutt Oceans J continents and that is attached to the crust (i.e., moves with the 1989 Mooney and Braile N-America A continental plates). -

Physiography of the Seafloor Hypsometric Curve for Earth’S Solid Surface

OCN 201 Physiography of the Seafloor Hypsometric Curve for Earth’s solid surface Note histogram Hypsometric curve of Earth shows two modes. Hypsometric curve of Venus shows only one! Why? Ocean Depth vs. Height of the Land Why do we have dry land? • Solid surface of Earth is Hypsometric curve dominated by two levels: – Land with a mean elevation of +840 m = 0.5 mi. (29% of Earth surface area). – Ocean floor with mean depth of -3800 m = 2.4 mi. (71% of Earth surface area). If Earth were smooth, depth of oceans would be 2450 m = 1.5 mi. over the entire globe! Origin of Continents and Oceans • Crust is formed by differentiation from mantle. • A small fraction of mantle melts. • Melt has a different composition from mantle. • Melt rises to form crust, of two types: 1) Oceanic 2) Continental Two Types of Crust on Earth • Oceanic Crust – About 6 km thick – Density is 2.9 g/cm3 – Bulk composition: basalt (Hawaiian islands are made of basalt.) • Continental Crust – About 35 km thick – Density is 2.7 g/cm3 – Bulk composition: andesite Concept of Isostasy: I If I drop a several blocks of wood into a bucket of water, which block will float higher? A. A thick block made of dense wood (koa or oak) B. A thin block made of light wood (balsa or pine) C. A thick block made of light wood (balsa or pine) D. A thin block made of dense wood (koa or oak) Concept of Isostasy: II • Derived from Greek: – Iso equal – Stasia standing • Density and thickness of a body determine how high it will float (and how deep it will sink). -

Label and Describe the Earth Diagram

Name_________________________class______ Label and Describe the Earth Diagram Read the definitions then use the information to color code, label and describe IN YOUR OWN WORDS each section of the diagram below. Definitions: crust – (green) the rigid, rocky outer surface of the Earth, composed mostly of basalt and granite. The crust is the thinnest of all layers. It is thicker on continents & thinner under the oceans. inner core – (gray) the solid iron-nickel center of the Earth that is very hot and under great pressure. mantle – (orange) a rocky layer located under the crust - it is composed of silicon, oxygen, magnesium, iron, aluminum, and calcium. Convection (heat) currents carry heat from the hot inner mantle to the cooler outer mantle. outer core – (red) the molten iron-nickel layer that surrounds the inner core. ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________ Name_________________________________cLass________ Label the OUTER LAYERS of the Earth This is a cross section of only the upper layers of the Earth’s surface. Read the definitions below and use the information to locate label and describe IN TWO WORDS the outer layers of the Earth. One has been done for you. continental crust – thick, top Continental Crust – (green) the thick parts of the Earth's crust, not located under the ocean; makes up the comtinents. Oceanic Crust – (brown) thinner more dense parts of the Earth's crust located under the oceans. Ocean – (blue) large bodies of water sitting atop oceanic crust. Lithosphere– (outline in black) made of BOTH the crust plus the rigid upper part of the upper mantle. -

Marine Science and Oceanography

Marine Science and Oceanography Marine geology- study of the ocean floor Physical oceanography- study of waves, currents, and tides Marine biology– study of nature and distribution of marine organisms Chemical Oceanography- study of the dissolved chemicals in seawater Marine engineering- design and construction of structures used in or on the ocean. Marine Science, or Oceanography, integrates different sciences. 1 2 1 The Sea Floor: Key Ideas * The seafloor has two distinct regions: continental margins and deep-ocean basins * The continental margin is the relatively shallow ocean floor near shore. It shares the structure and composition of the adjacent continent. * The deep-ocean floor differs from the continental margin in tectonic origin, history and composition. * New technology has allowed scientists to accurately map even the deepest ocean trenches. 3 Bathymetry: The Study of Ocean Floor Contours Satellite altimetry measures the sea surface height from orbit. Satellites can bounce 1,000 pulses of radar energy off the ocean surface every second. With the use of satellite altimetry, sea surface levels can be measured more accurately, showing sea surface distortion. 4 2 5 The Physiography of the Ocean Floor Physiography and bathymetry (submarine landscape) allow the sea floor to be subdivided into three distinct provinces: (1) continental margins, (2) deep ocean basins and (3) mid-oceanic ridges. 6 3 The Topography of Ocean Floors The classifications of ocean floor: Continental Margins – the submerged outer edge of a continent Ocean Basin – the deep seafloor beyond the continental margin Ocean Ridge System - extends throughout the ocean basins A typical cross section of the Atlantic ocean basin. -

Plate Boundaries - Where the Action Is! Modeling Activity

Plate Boundaries - Where the action is! Modeling Activity The Earth’s outer shell, called the lithosphere, is broken up into tectonic plates. The lithosphere is rock that is rigid and brittle - it is composed of the crust and the uppermost mantle. The rigid plates move around on top of a hotter more mobile layer of the mantle known as the asthenosphere. Where the plates meet is where most of the world’s earthquakes and volcanic activity occurs. Let’s explore what happens at different plate boundaries. What you need: • Graham crackers • Waxed paper • Peanut butter or frosting and a knife to spread • Small bowl of water PUSH Set up: • Spread peanut butter or frosting on the waxed paper. Cover an area almost twice the size of a whole graham cracker. This is the asthenosphere – soft and mobile. • Break a graham cracker in half, now you have two tectonic plates. The PULL plates are rigid and brittle. When you broke the graham cracker... you caused an earthquake! What you’ll do: Place two graham cracker halves (tectonic plates) on your asthenosphere. Using one finger on each plate, very slowly and gently move your plates around on the asthenosphere. This is how tectonic plates on the Earth’s asthe- nosphere move. Now let’s check out the different types of boundaries between plates. Divergent Plate Boundary These are boundaries where two plates move away from each other. These boundaries are often found on ocean floors. Put the two graham cracker halves (tectonic plates) touching each other in the middle of your asthenosphere. -

Continental Crust - Irina M

GEOPHYSICS AND GEOCHEMISTRY – Vol.II - Continental Crust - Irina M. Artemieva CONTINENTAL CRUST Irina M. Artemieva Uppsala University, Sweden Keywords:Anisotropy, brittle crust, composition, continental arc, continental margin, cratons, crustal thickness, crustal types, ductile crust, extended crust, juvenile crust, lower crust, Moho discontinuity, Orogens, plate tectonics, platforms, Poisson’s ratio, Rift, reflectivity, Rheology, seismic velocities, shear-wave splitting, shields, subcrustal velocity, transitional crust, upper crust, upper mantle Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods of Continental Crust Studies 2.1 Seismic Studies 2.2 Geologic Mapping 2.3 Petrologic Studies 2.4 Heat Flow Studies 2.5 Electromagnetic Studies 2.6 Gravity Studies 2.7 Laboratory Ultrasonic Measurements 2.8 Continental Drilling 2.9 Geochronology 3. Average Seismic Structure of Continental Crust 3.1 Crustal Thickness and Seismic Velocities 3.2 Crustal Reflectivity 3.3 The Moho Discontinuity 4. Types of Continental Crust 4.1 Shields and Platforms 4.2 Collisional Orogens 4.3 Continental Rifts and Extended Crust 4.4 Continental Margins 5. Physical Properties of Continental Crust 5.1 Seismic Velocities in Typical Crustal Rocks 5.2 Seismic Anisotropy in Continental Crust 5.3 Poisson’sUNESCO Ratio – EOLSS 5.4 Crustal Density 5.5 Crustal Rheology,SAMPLE Brittle-Ductile Crust CHAPTERS 6. Composition of Continental Crust 6.1 Methods of Estimating Crustal Composition 6.2 The Upper and Middle Continental Crust 6.3 The Lower Continental Crust 7. Crustal Evolution 7.1 Hypotheses for the Continental Crust Origin 7.2 Age Distribution of Continental Crust 7.3 The Formation of Continental Crust and Mantle Dynamics Acknowledgments ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) GEOPHYSICS AND GEOCHEMISTRY – Vol.II - Continental Crust - Irina M. -

Lithospheric Strength Profiles

21 LITHOSPHERIC STRENGTH PROFILES To study the mechanical response of the lithosphere to various types of forces, one has to take into account its rheology, which means knowing how it flows. As a scientific discipline, rheology describes the interactions between strain, stress and time. Strain and stress depend on the thermal structure, the fluid content, the thickness of compositional layers and various boundary conditions. The amount of time during which the load is applied is an important factor. - At the time scale of seismic waves, up to hundreds of seconds, the sub-crustal mantle behaves elastically down deep within the asthenosphere. - Over a few to thousands of years (e.g. load of ice cap), the mantle flows like a viscous fluid. - On long geological times (more than 1 million years), the upper crust and the upper mantle behave also as thin elastic and plastic plates that overlie an inviscid (i.e. with no viscosity) substratum. The dimensionless Deborah number D, summarized as natural response time/experimental observation time, is a measure of the influence of time on flow properties. Elasticity, plastic yielding, and viscous creep are therefore ingredients of the mechanical behavior of Earth materials. Each of these three modes will be considered in assessing flow processes in the lithosphere; these mechanical attributes are expressed in terms of lithospheric strength. This strength is estimated by integrating yield stress with depth. The current state of knowledge of rock rheology is sufficient to provide broad general outlines of mechanical behavior but also has important limitations. Two very thorny problems involve the scaling of rock properties with long periods and for very large length scales. -

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

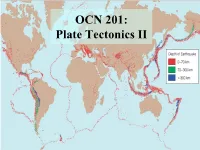

OCN 201: Plate Tectonics II There are three types of plate boundaries: a) mid-ocean ridge, subduction zone, transform fault b) divergent, convergent, translational c) constructive, destructive, conservative d) All of the above: a,b, and c all describe the 3 types. Structure of Continents • Continental crust has formed throughout Earth’s history by chemical differentiation at subduction zones. – Oceanic crust: dry melting of mantle at MOR basalt – Continental crust: wet melting in subduction zones andesite of volcanic arcs Subducted H2O is from the oceans, in seafloor sediment and weathered oceanic crust. H2O comes off subducted plate as it heats, rises into mantle of plate above, and X lowers its melting temperature. Structure of Continents Continental crust exists on Earth because we have – Liquid water oceans – Subduction (Plate Tectonics) – Venus lacks liquid H2O and subduction zones no continental crust (and Venus’s mantle is too stiff and dry to convect!) Hypsometric curves: Shape of the solid surface of Earth vs. Venus Structure of Continents Oldest oceanic crust ~ 170 million years Oldest continental crust = 4.03 billion years (in Canada) What do the continents tell us about Earth history? Cratons vs. mobile belts: Terranes and Structure of Continents • Continental crust is too thick and buoyant to subduct. • When continental fragment or island arc collides with continent it “sticks”. Terranes and Structure of Continents • Fragments of cont. crust incorporated into larger cont. masses are called terranes. • Younger terranes are parts of mobile belts. • Older now stable parts (cratons) appear to have accreted as terranes in the more distant past. Terrane Structure of North America • North America age distribution illustrates terrane accretion. -

Layers of the Earth

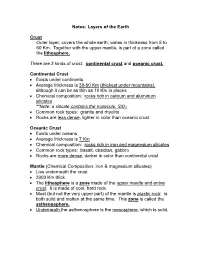

Notes: Layers of the Earth Crust Outer layer; covers the whole earth; varies in thickness from 5 to 60 Km. Together with the upper mantle, is part of a zone called the lithosphere. There are 2 kinds of crust: continental crust and oceanic crust. Continental Crust Exists under continents Average thickness is 30-50 Km (thickest under mountains), although it can be as thin as 10 Km in places Chemical composition: rocks rich in calcium and aluminum silicates **Note: a silicate contains the molecule, SiO2 Common rock types: granite and rhyolite Rocks are less dense, lighter in color than oceanic crust Oceanic Crust Exists under oceans Average thickness is 7 Km Chemical composition: rocks rich in iron and magnesium silicates Common rock types: basalt, obsidian, gabbro Rocks are more dense, darker in color than continental crust Mantle (Chemical Composition: iron & magnesium silicates) Lies underneath the crust 2900 Km thick The lithosphere is a zone made of the upper mantle and entire crust. It is made of cool, hard rock. Most (but not the very upper part) of the mantle is plastic rock: is both solid and molten at the same time. This zone is called the asthenosphere. Underneath the asthenosphere is the mesosphere, which is solid. The asthenosphere has convection currents, where matter rises to the top, cools, then comes back down again, in a continuous cycle. Core Center of the Earth; ~ 3500 Km thick Outer Core Made of molten iron and nickel 2270 Km thick Inner Core Made of solid iron and nickel. Is solid because of the extreme pressures it is under. -

Crust and Mantle Vs. Lithosphere and Asthenosphere

Crust and Mantle vs. Lithosphere and Asthenosphere Why do we use two names to describe the same layer of the Earth? Well, this confusion results from the different ways scientists study the Earth. Lithosphere, asthenosphere, and mesosphere (we usually don't discuss this last layer) represent changes in the mechanical properties of the Earth. Crust and mantle refer to changes in the chemical composition of the Earth. Lithosphere and Asthenosphere The lithosphere (litho:rock; sphere:layer) is the strong, upper 100 km of the Earth. The lithosphere is the tectonic plate we talk about in plate tectonics. The asthenosphere (a:without; stheno:strength) is the weak and easily deformed layer of the Earth that acts as a “lubricant” for the tectonic plates to slide over. The asthenosphere extends from 100 km depth to 660 km beneath the Earth's surface. Beneath the asthenosphere is the mesosphere, another strong layer. Crust and Mantle The crust is a chemically distinct layer at the surface of the Earth. Crustal material contains lighter elements like Si, O, Al, Ca, K, Na, etc... Feldspars (Anorthite, Albite, Orthoclase) are comon minerals in the crust (CaAL2Si2O8, NaALSi3O8 , KALSi3O8). The crust may be divided into 2 types: oceanic and continental. Oceanic crust is usually 5-10 km thick and continental crust is 33 km thick on average. Beneath the crust is the mantle. The mantle is made up of Si and O, like the crust, but it contains more Fe and Mg. Thus, Olivine (Fe2SiO4-Mg2SiO4) and pyroxene (MgSiO3-FeSiO3) are abundant in the mantle. The mantle extends to the core-mantle interface at approximately 2900 km depth.