The Anglo-American Reception of Carl Schmitt from the 1930S to the Early 2000S Benjamin T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infoblatt Ediger-Eller

Informationen für das Leben in Ediger-Eller ORTSBÜRGERMEISTERIN & BEIGEORDNETE Ortsbürgermeisterin [email protected] 02675 272 9807 Heidi Hennen-Servaty 1.Beigeordneter 02675 1450 Helmut Brück Beigeordneter 02675 911 90 41 Bernhard Himmen Sprechstunde montags, Gemeindehaus, Tel 02675 911970 17.30 Uhr bis 19.00 Uhr Am Pfirsichgarten 39 NOTRUFE Polizei 110 Feuerwehr 112 Defibrillator – im Eingangsbereich der Raiffeisenbank , Moselweinstr. 38, Ediger Krankentransport (DRK) Cochem 02671 19222 Marienkrankhaus Cochem 02671 985-0 Avallonstr. 32, 56812 Cochem St. Josef-Krankenhaus Zell 06542 97-0 Ambulantes Hilfezentrum der Caritas, 06542 969778-0 Winzerstr. 7, Zell Ambulantes Kranken- und Altenpflegeteam 02672 910183 Pommern Notaufnahme für pflegebedürftige Senioren 02671 60709 Seniorenresidenz „Pro Seniore“, Cochem-Sehl Tagespflege für Senioren und Menschen mit 02671 6008-470 Demenz, Moselstr. 37, 56814 Ernst Entgiftungszentrale Mainz 06131 232466 oder 06131 19240 Kinder-Notruf-Telefon 02671 614444 Weißer Ring – Hilfe für Kriminalitätsopfer 116006 (kostenfrei) oder 0151 55164663 Frauenhaus Koblenz 0261 9421020 Frauenhaus Trier 0651 49511 Notruf e.V. Trier 0651 49777 Polizeiinspektion Cochem 02671 984-0 Kriminalinspektion Mayen 02651 801-0 Telefonseelsorge 0800 1110111 BEREITSCHAFTSDIENSTE (an Wochenenden, mittwochnachmittags sowie an Feiertagen) Ärztlicher Bereitschaftsdienst, Marien- 116117 krankenhaus Cochem, Avallonstr. 32 Zahnärztlicher Bereitschaftsdienst 0180 5040308 (12 ct/Min.) Augenärztlicher Bereitschaftsdienst 0651 2082244 Apothekenbereitschaft 0180 5-258825 plus Postleitzahl des Standortes Abwasserwerk Verbandsgemeinde Co- 0171 206 89 58 chem Kreiswasserwerk Cochem-Zell 0160 9786 9516 Westnetz GmbH – Störung Strom 0800 4112244 Telekom – Störung Festnetz 0800 3301000 ÄRZTE Hausärzte Dr. Ruhl Pfirsichgarten 3, Eller 02675 249 Dr. Amin Brauheck-Center, Cochem 02671 285 Dr. Dr. Rolf Gartner Ravenéstr. 18-20, Cochem 02671 8500 Dr. -

Les Représentations Médiatiques De La Vieillesse Dans La Société Française Contemporaine

Les repr´esentations m´ediatiquesde la vieillesse dans la soci´et´efran¸caisecontemporaine : ambigu¨ıt´esdes discours et r´ealit´essociales Yannick Sauveur To cite this version: Yannick Sauveur. Les repr´esentations m´ediatiques de la vieillesse dans la soci´et´efran¸caise contemporaine : ambigu¨ıt´esdes discours et r´ealit´essociales. Sciences de l'information et de la communication. Universit´ede Bourgogne, 2011. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2011DIJOL015>. <tel- 00665923> HAL Id: tel-00665923 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00665923 Submitted on 3 Feb 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. UNIVERSITE DE BOURGOGNE THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l‟Université de Bourgogne Discipline : Sciences de l‟Information et de la Communication par Yannick Sauveur Les représentations médiatiques de la vieillesse dans la société française contemporaine Ambiguïtés des discours et réalités sociales Thèse dirigée par Pascal Lardellier Soutenue le mercredi 22 juin 2011 Jury M. Jean-Jacques BOUTAUD, Professeur, Université de Bourgogne, Mme Michèle DION, Professeur, Université de Bourgogne, M. Claude JAVEAU, Professeur émérite, Université Libre de Bruxelles, M. Pascal LARDELLIER, Professeur, Université de Bourgogne, Directeur de la thèse, M. -

Landschaftsplanverzeichnis Rheinland-Pfalz

Landschaftsplanverzeichnis Rheinland-Pfalz Dieses Verzeichnis enthält die dem Bundesamt für Naturschutz gemeldeten Datensätze mit Stand 15.11.2010. Für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit der gemeldeten Daten übernimmt das BfN keine Gewähr. Titel Landkreise Gemeinden [+Ortsteile] Fläche Einwohner Maßstäbe Auftraggeber Planungsstellen Planstand weitere qkm Informationen LP Adenau Ahrweiler Adenau 257 13.000 10.000 VG Adenau Brandenfels 1974; 1974 Od 130 LP Adenau (1.FS) Ahrweiler Adenau 257 13.000 5.000 VG Adenau, Uni. Inst. f. Städtebau, Uni 1988; 1989 10.000 Bonn Bonn / Oyen LP Adenau (2.FS) Ahrweiler Adenau 258 15.423 10.000 VG Adenau Nick, C+S Consult 1996 LP Altenahr Ahrweiler Ahrbrück, Altenahr, Berg, Dernau, 153 11.200 10.000 VG Ahrweiler Brandenfels u. Pahl 1984 Heckenbach, Hönningen, Kalenborn, Kesseling, Kirchsahr, Lind, Mayschoß, Rech LP Altenahr (FS) Ahrweiler Ahrbrück, Altenahr, Berg, Dernau, 154 12.000 5.000 VG Altenahr Bauabteilung i.B. Heckenbach, Hönningen, 10.000 Kalenborn, Kesseling, Kirchsahr, Lind, Mayschoß, Rech LP Bad Breisig Ahrweiler Bad Breisig, Brohl-Lützing, 50 10.100 5.000 VG Bad Breisig LSRP 1984 Gönnersdorf, Waldorf 10.000 LP Bad Breisig (FS) Ahrweiler Bad Breisig, Brohl-Lützing, 42 13.027 5.000 VG Bad Breisig Sprengnetter u. i.B. Gönnersdorf, Waldorf 10.000 Partner LP Bad Ahrweiler Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 64 28.300 10.000 ST Bad Neuenahr Penker 1976; 1976 Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 50.000 LP Bad Ahrweiler Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 63 27.456 10.000 ST Bad Neuenahr Terporten i.B. Neuenahr-Ahrweiler (FS) LP Brohltal Ahrweiler -

Ausgabe 34/2020

Vulkan Echo Mitteilungsblatt mit den öfentlichen Bekanntmachungen der VERBANDSGEMEINDE ULMEN Mit den Kreisnachrichten des Kreises CoChem-Zell Jahrgang 50 Samstag, den 22. August 2020 Ausgabe 34/2020 Schulstart in Corona-Zeiten Am vergangenen Montag hat die Schule für alle unsere Schülerinnen und Schü- ler wieder begonnen. Dieser Schulstart nach den Sommerferien ist besonders, da das vergangene Schuljahr von den Erfahrungen und Erschwernissen der Corona- Pandemie geprägt war. Umso aufregender wird der Beginn des neuen Schuljahres 2020/21 für die Schüler-/innen, Lehrer-/innen und Eltern sein. Ich hofe, dass die Infektionszahlen es zulassen, in unseren heimischen Schulen den Regelbetrieb für alle Schülerinnen und Schüler beizubehalten. Die letzten Monate haben uns deutlich gezeigt, welche wichtigen Aufgaben unsere Schulen und auch die Kin- dertagesstätten in unserer Gesellschaft einnehmen. Unsere Einrichtungen und Schulen sind auf die verschiedenen denkbaren Szenarien vorbereitet, um den Kindern und Jugendlichen das Recht auf Bildung in bester Weise zu ermöglichen. Den Schulleitungen und den Kindertagestätten unserer Verbandsgemeinde Ulmen habe ich meine Unterstützung und die Unterstützung meiner Mitarbei- ter zugesagt, um die Bildungs-, Betreuungs- und Erziehungsarbeit für alle Kinder und Jugendlichen weiterhin in jeder Lage sicherzustellen. Ich wünsche den Kindern in den Kindertagesstätten viel Spaß und schöne Erfah- rungen und den Schülerinnen und Schülern eine interessante und lehrreiche Schulzeit! Ihr Bürgermeister Alfred Steimers www.ulmen.de -

Masculinity and Political Authority 241 7.1 Introduction 241

Durham E-Theses The political uses of identity an enthnography of the northern league Fernandes, Vasco Sérgio Costa How to cite: Fernandes, Vasco Sérgio Costa (2009) The political uses of identity an enthnography of the northern league, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2080/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham The Political Uses of Identity: An Ethnography of the Northern The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was League submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. By Vasco Sergio Costa Fernandes Department of Anthropology April 2009 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Dr Paul Sant Cassia Dr Peter Collins 2 1 MAY 2009 Abstract This is a thesis about the Northern League {Lega Nord), a regionalist and nationalist party that rose to prominence during the last three decades in the north of Italy Throughout this period the Northern League developed from a peripheral and protest movement, into an important government force. -

Naturerlebnis Zwischen Eifel Und Hunsrück Ferienland Cochem – Wir Bieten Alles Außer Alltag! Wirfus

Dortmund Herrliche Wandertouren, Tipps und tolle Wege So erreichen Sie uns: Venlo Mit dem Auto: A 48 Abfahrt Kaisersesch aus Richtung Wuppertal Koblenz. Abfahrt Ulmen aus Richtung Trier. 45 Niederlande Mönchen- Mit der Bahn: Moselstrecke Trier-Koblenz mit sieben gladbach Leverkusen Bahnhöfen im Ferienland Cochem: Cochem u. Treis- Karden (Regionalexpress u. Regionalbahn), Ediger-Eller, 4 Klotten, Pommern, Müden u. Moselkern (jeweils Köln 4 Siegen Regionalbahn). 61 Aachen Bonn 45 Mit dem Flugzeug: Vom Hunsrück-Airport Frankfurt- 3 Hahn gibt es einen Shuttle-Bus, direkt nach Cochem. AB Kreuz Infos u. Online-Reservierung unter: www.airportshuttle- Belgien Meckenheim Bad mosel.de AB Dreieck Neuenahr Dernbach AB Kreuz Koblenz Mendig Koblenz Mayen 3 EIFEL Kaisersesch Karten und Infomaterial: St. Vith 48 • Gastgeberverzeichnis Cochem Frankfurt 60 1 61 am Main Zell • Rad- und Wanderkarten Wittlich Bingen Airport AB Dreieck • Mosel.Erlebnis.Route Luxemburg Hahn Nahetal Mainz Trier • Wanderkarte Ferienland Cochem • Moselsteig Die Orte im Ferienland Cochem: Moselkern Greimersburg Wirfus Müden -Karden Pommern Klotten Lütz Treis- Valwig · 20_04 Verlag digIT Lieg Faid Cochem Tourist-Information Ernst Bruttig- Dohr Ferienland Cochem Fankel Ellenz- Endertplatz 1 · 56812 Cochem Poltersdorf Beilstein Bremm Tel. +49 (0) 2671- 6004-0 Ediger-Eller Fax +49 (0) 2671- 6004-44 Briedern Mesenich [email protected] Nehren Senhals www.ferienland-cochem.de Senheim www.cochem.de www.facebook.com/ferienlandcochem Angaben ohne Gewähr! Änderungen vorbehalten. Alle Die Urlaubsregion Ferienland Cochem erstreckt sich vom Bremmer Calmont über Cochem bis hin nach Moselkern. Die Stadt Cochem sowie 22 Ferienorte bieten gesunde Erholung und vielfältige Aktivitäten – kurz gesagt eine Region mit hohem Erlebnis- und Erho- Hier finden Sie die Entdeckungspfade im Ferienland Cochem: lungswert. -

Conversation Avec Julien Freund

Conversation avec Julien Freund par Pierre Bérard http://asymetria-anticariat.blogspot.com Julien Freund est mort en septembre 1993. De la fin des ann ées 70 jusqu©à son décès, je l©ai rencontré à maintes reprises tant à Strasbourg que chez lui à Villé et dans ces villes d©Europe où nous réunissaient colloques et conférences. Des heures durant j©ai frotté à sa patience et à sa perspicacité les grands thèmes de la Nouvelle Droite. Il les accueillait souvent avec une complicit é rieuse, parfois avec scepticisme, toujours avec la franche ind épendance d©esprit qui a marqué toute son existence. Les lignes qui suivent mettent en sc ène des conversations tenues à la fin des années quatre-vingt. Des notes prises alors sur le vif et des souvenirs demeurés fort intenses m©ont permis de reconstituer par bribe certains de ces moments. Bien entendu, il ne s©agit pas d©utiliser ici le biais de la fiction posthume pour prêter à Julien Freund des propos que les calomniateurs dont on connaît l©acharnement pourraient instrumenter contre la mémoire d©un grand maître. C©est pourquoi j©entends assumer l©entière responsabilité de ce dialogue. Lors de ces entrevues, on le devine, l©ami absent mais souvent évoqué était Alain de Benoist. Ce texte lui est dédié. J.F. - Vous êtes à l'heure, c'est bien ! Visage plein, barré d'un large sourire, Julien Freund se tient sur le pas de sa porte. - J'ai réservé à l'endroit habituel, poursuit-il. Il enfile un anorak, ajuste un béret sur une brosse impeccable et se saisit de sa canne. -

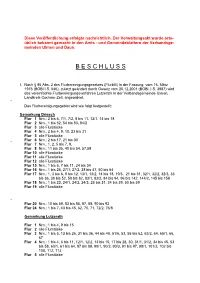

B E S C H L U S S

Diese Veröffentlichung erfolgte nachrichtlich. Der Verwaltungsakt wurde orts- üblich bekannt gemacht in den Amts - und Gemeindeblättern der Verbandsge- meinden Ulmen und Daun. B E S C H L U S S I. Nach § 86 Abs. 2 des Flurbereinigungsgesetzes (FlurbG) in der Fassung vom 16. März 1976 (BGBl I S. 546), zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 20.12.2001 (BGBl. I S. 3987) wird das vereinfachte Flurbereinigungsverfahren Lutzerath in der Verbandsgemeinde Ulmen, Landkreis Cochem-Zell, angeordnet. - Das Flurbereinigungsgebiet wird wie folgt festgestellt: Gemarkung Driesch Flur 1 Nrn.: 2 bis 6, 7/1, 7/2, 8 bis 11, 12/1, 14 bis 18 Flur 2 Nrn.: 1 bis 52, 54 bis 83, 84/2 Flur 3 alle Flurstücke Flur 4 Nrn.: 2 bis 4, 9, 10, 23 bis 31 Flur 5 alle Flurstücke - Flur 6 Nrn.: 2 bis 17, 21 bis 30 Flur 7 Nrn.: 1, 2, 5 bis 7, 9, Flur 8 Nrn.: 11 bis 35, 40 bis 54, 57,59 Flur 10 alle Flurstücke Flur 11 alle Flurstücke Flur 12 alle Flurstücke Flur 15 Nrn.: 1 bis 5, 7 bis 11, 24 bis 34 Flur 16 Nrn.: 1 bis 26, 27/1, 27/2, 28 bis 47, 50 bis 64 Flur 17 Nrn.: 1, 3 bis 6, 8 bis 12. 13/1, 13/2, 14 bis 18, 19/3, 21 bis 31, 32/1, 32/2, 32/3, 33 bis 36, 38 bis 52, 58 bis 82, 83/1, 83/2, 84 bis 94, 96 bis 142, 144/2, 145 bis 158 Flur 18 Nrn.: 1 bis 23, 24/1, 24/2, 24/3, 25 bis 31, 34 bis 39, 50 bis 59 Flur 19 alle Flurstücke - Flur 20 Nrn.: 10 bis 59, 83 bis 85, 87, 88, 90 bis 92 Flur 24 Nrn.: 1 bis 7, 43 bis 45, 62, 70, 71, 72/2, 76/8 Gemarkung Lutzerath Flur 1 Nrn.: 1 bis 4, 9 bis 15 Flur 2 alle Flurstücke Flur 3 Nrn.: 1 bis 5, 13 bis 26, 31 bis 36, 44 bis 48, 51/6, 53, 55 -

Julien Freund

Article paru dans Le Spectacle du monde (juillet 2008) JULIEN FREUND Pour désigner ceux qui veulent faire de la politique ou prétendent en parler sans savoir ce qu’elle est, Julien Freund avait un terme de prédilection : l’impolitique. Une forme classique d’impolitique consiste à croire que les fins du politique peuvent être déterminées par des catégories qui lui sont étrangères, économiques, esthétiques, morales ou éthiques principalement. Impolitique est aussi l’idée que la politique a pour objet de réaliser une quelconque fin dernière de l’humanité, comme le bonheur, la liberté en soi, l’égalité absolue, la justice universelle ou la paix éternelle. Impolitique encore, l’idée que « tout est politique » (car si la politique est partout, elle n’est plus nulle part), ou encore celle, très à la mode aujourd’hui, selon laquelle la politique se réduit à la gestion administrative ou à une « gouvernance » inspirée du management des grandes entreprises. Mais alors qu’est-ce que la politique ? Quels sont ses moyens ? Sa finalité ? C’est à ces questions que Julien Freund, décrit aujourd’hui par Pierre-André Taguieff comme « l’un des rares penseurs du politique que la France a vu naître au XX e siècle », s’est employé à répondre dans la quinzaine d’ouvrages de philosophie politique, de sociologie et de polémologie qu’il publia au cours de son existence. Né le 9 janvier 1921 dans le village mosellan de Henridorff, d’une mère paysanne et d’un père ouvrier socialiste, Julien Freund était l’aîné de six enfants. Son père étant mort très tôt, il devient instituteur à l’âge de dix-sept ans. -

Energieberater Im Landkreis Cochem-Zell Name Vorname Straße Plz Ort Gelistet Bei Beruf, Fachrichtung Usw. Fröhlich Jürgen

Energieberater im Landkreis Cochem-Zell Name Vorname Straße Plz Ort Gelistet bei Beruf, Fachrichtung usw. Fröhlich Jürgen Gartenweg 17 56754 Brohl BAFA, HWK Koblenz, EOR Techniker, Fachrichtung Holz Wagner Hans-Peter Hauptstr. 30 56820 Briedern EOR Architekt Gerlich Roland Josef-von-Lauff-Str. 31 56812 Cochem HWK Koblenz Dipl-Ing. Maschinenbau Pauly Benno Kapellenstr. 35 56812 Cochem BAFA, EOR Ingenieurbüro für Baustatik Holl Jürgen Ellerbachweg 12 56814 Ediger-Eller EOR Architekt Balthasar Stefan Kernstr. 44 56818 Klotten HWK Koblenz Schornsteinfeger Bertram Timo Obere Brühlstr. 9 56818 Klotten HWK Koblenz Schornsteinfeger Hennen Udo Alte Mayener Straße 6 56759 Kaisersesch EOR Baufirma Juchem Klaus-Werner In der Trift 10 56759 Kaisersesch HWK Koblenz, EOR Bau-Ingenieur Jung Heike Masburger Straße 40 56759 Kaisersesch EOR Klode Patrick Am Römerturm 2 56759 Kaisersesch BAFA, HWK Koblenz Umweltschutztechniker Neef Andreas Masburger Straße 40 56759 Kaisersesch EOR Ingenieurbüro Schneiders Jürgen Marienau 3 56759 Kaisersesch EOR Architekturbüro Schnitzler Matthias Eichenstr. 17 56759 Kaisersesch BAFA, EOR Selbständiger Energieberater Engelmann Gerd Kehriger Str. 9 56761 Kaifenheim HWK Koblenz Zimmerer, Dachdecker Stein Heinz Armin Hauptstr. 68 56858 Mittelstrimmig BAFA, EOR Maurer, Hochbautechniker Klippel Alexandra Birkenweg 9 56290 Mörsdorf BAFA Färber Hans-Peter Birkenweg 9 56290 Mörsdorf BAFA, KfW Peters Dieter Wagenweg 15A 56761 Müllenbach HWK Koblenz Marke Jens Moselweinstraße 33 56820 Senheim KfW Dreis Simone Eifel-Maar-Park 2 56766 Ulmen HWK Trier Energiesysteme Hirschler Frank Dechant-Bungart-Str. 7 56766 Ulmen BAFA, HWK Koblenz, EOR Bautechniker Seip Richard Kleewiesenweg 29 56766 Ulmen HWK Koblenz, EOR Heizungsbauer Arenz Reiner Lerchenweg 3 56812 Valwig EOR Architekturbüro Andres Jürgen Corray 59 56856 Zell HWK Koblenz, EOR Malermeister Reek-Berghäuser Kerstin August-Horch-Straße 6-8 56070 Koblenz Handwerkskammer Koblenz Schwarzmeier Volker Schlossstr. -

The Myth of National Defense, Hoppe

THE MYTH OF NATIONAL DEFENSE: ESSAYSONTHE THEORY AND HISTORY OF SECURITY PRODUCTION EDITED BY HANS-HERMANN HOPPE THE MYTH OF NATIONAL DEFENSE: ESSAYSONTHE THEORY AND HISTORY OF SECURITY PRODUCTION Copyright © 2003 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute Indexes prepared by Brad Edmonds All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832. ISBN: 0-945466-37-4 To the memory of Gustave de Molinari (1819–1911) Patrons The Mises Institute dedicates this volume to all of its generous donors, and in particular wishes to thank these Patrons: Don Printz, M.D., Mrs. Floy Johnson, Mr. and Mrs. R. Nelson Nash, Mr. Abe Siemens ^ Mr. Steven R. Berger, Mr. Douglas E. French, Mr. and Mrs. Richard D. Riemann (top dog™), Mr. and Mrs. Joseph P. Schirrick, Mr. and Mrs. Charles R. Sebrell, In memory of Jeannette Zummo, Mr. W.A. Richardson ^ Anonymous, Mr. Steven R. Berger, Mr. Richard Bleiberg, Mr. John Hamilton Bolstad, Mr. Herbert Borbe, Mr. and Mrs. John C. Cooke, Dr. Larry J. Eshelman, Bud Evans (Harley-Davidson of Reno), Mrs. Annabelle Fetterman, Mr. and Mrs. Willard Fischer, The Dolphin Sky Foundation, Mr. Frank W. Heemstra, Mr. Albert L. Hillman, Jr., Richard J. Kossmann, M.D., Mrs. Sarah Paris Kraft, Mr. David Kramer, Mr. Frederick L. Maier, Mr. and Mrs. William W. Massey, Jr., Mr. Norbert McLuckie, Mr. -

Regionalism, Federalism and Minority Rights: the I Talian Case

Regionalism, federalism and minority rights: The I talian case Mario DIANI Mario Diani is Professor of Sociology in the Departme nt of Government of the Uni versity of Strathclyde, Glasgow. 1. Introduction Most domestic and foreign observers have usually emphasized Italy's cultural heterogeneity and weak national identity. When the country was at last officially unified in 1870, only the 10% most cultivated citizens could use the national lan guage to communicate; over a century later, in the early 1990s, about 14% of the population are, according to some estimates, still restricted to local dialects; of the twenty-eight minority languages identified by the European Union within member states, thirteen are spoken by minorities located within the Italian bor ders. Altogether, these groups exceed one million people (Lepschy, 1990; De Mau ro, 1994; Adnkronos, 1995: 856). Whether these and other sources of cultural variation - e.g., those reflected in the North-South divide - are big enough to result in open cultural fragmentation within the country is however another question. Many claim indeed that shared mentalities and lifestyles nonetheless provide Italians with a relatively homoge neous culture and identity (Romano, 1994). This view is apparently supported by recent figures about feelings of national identification. In spite of recent suc cesses of political,9rganizations advocating a drastic reform of the unified state, and occasionally threatening its dissolution, Italians still overwhelmingly concei ve of themselves as fellow nationals in the first place, while only tiny minorities regard regional (Venetian, Lombard, Piedmontese, etc.) origins as their major sour 1 ces of collective identity . Rather than from strictly cultural reasons, major problems to ltalian successful integration have seemingly come from politica! and socio-economie dynamics, related to nation building.