Quiet Crisis: Homelessness and At-Risk in Greater Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galloping Goose and Lochside Trails

Maps and trail highlights inside How to get there From downtown Victoria, start at the corner of Wharf Street and Pandora Avenue. Cross the Johnson Street bridge, then turn right on the paved path that connects to Harbour Road and the Galloping Goose Trail. From the BC Ferries Terminal at Swartz Bay, follow the signs to the Lochside Trail. Cyclists: after passing under the GALLOPING Landsend Road overpass, turn right at the bicycle lane, right at the GALLOPING overpass, then right onto the Trail. Foot passengers: turn left at the Landsend Road overpass, then right onto the Trail. GOOSEGOOSE ANDAND From Victoria International Airport, follow the signs to Victoria. Turn left on McTavish Road, cross the Patricia Bay Highway, then turn right onto the Lochside Trail, which follows Lochside Drive. LOCHSIDELOCHSIDE Transit and the trails BC Transit buses can carry R EG ILS you to or from the trails on several routes. Low floor buses on ION TRA route 70 between Victoria and Swartz Bay, and route 61 between AL Victoria and Sooke are equipped with bike racks and wheelchair lifts. For details and schedules, phone BC Transit at (250) 382-6161 or visit www.bctransit.com. Need more info? CRD Parks coordinates the management and operations of your regional trails. To find out more about CRD Parks, and for information about trail closures or detours, visit www.crd.bc.ca/parks. Dial 9-1-1 in case of emergency or fire, or if you observe unlawful activities. This booklet is printed on New Leaf Reincarnation Matte, made with 100% recycled fibres, 50% post-consumer waste, and processed chlorine-free. -

Order in Council 42/1934

42 Approved and ordered this 12th day/doff January , A.D. 19 34 Administrator At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, arm~ame wane Aar. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Hart Mr. Gray Mn '!actersJn Mn !...acDonald Mn Weir Mn Sloan Mn ?earson Mn To His Honour strata r The LieLIRtneaftCOMPOtTrae in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend that, under the provisions of section 11 of the " Provincial Elections Act," the persons whose names appear hereunder be appointed, without salary, Provincial Elections Commissioners for the purposes of the said section 11 for the Electoral Districts in which they reside respectively, as follows :— ELECTORAL DISTRICT. NAME. ADDRESS. ESQUIMA IT Pilgrim, Mrs. Jemima Jane 1253 Woodway Ave.,Esquimall wins, John William Sooke Doran, John Patrick R.R. 2, Sooke Wilson, Albert Leslie Sooke Robinson, Robert William Colwood Yates, James Stuert Langford Wale, Albert Edward Langford Trace, John Luxton, via Colwood Field, Chester Gibb Metchosin Hearns, Henry 936 Craigflower Rd., Esq. Fraser, Neil 1264 Old Esquimalt Rd.,Esq. Hodgson, William 1219 Carlisle St., Mesher, James Frederick 1553 Esquimalt Rd., " Nicol, Mrs. Margaret 1411 Esquimalt Rd., " Clark, Mrs. Christina Jane Stuart Shirley, R.R.2, Sooke Alsdorf, Mrs. Katharine Iri s,Cobble Hill Barry, Mrs. Letitia Rosa Cobble Hill Barry, Tierney Patrick Cobble Hill Meiillan, Mrs. Barbara Ann Cobble Hill Dick, Robert Shawnigan Lake Havers, Arthur Robert Shawnigan Lake Garnett, George Grant Cobble Hill Dougan, Stephen David Cobble Hill Walker, Lady Emily Mary 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, Eric Henry James 649 Admirals Rd.,Esquimalt Walker, William Ure Jordan River Brown, Mrs. -

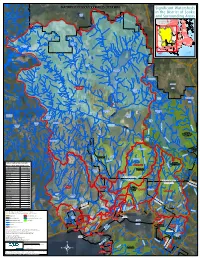

Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas

Shawnigan Lake C O W I C H A N V A L L E Y R E G I O N A L D I S T R I C T Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke Grant Lake and Surrounding Areas North C o w i c h a n V a l l e y Saanich R e g i o n a l D i s t r i c t Sidney OCelniptrahl ant Lake Saanich JdFEA H a r o S t r a Highlands it Saanich View Royal Juan de Fuca Langford Electoral Area Oak Bay Esquimalt Jarvis Colwood Victoria Lake Sooke Weeks Lake Metchosin Juan de Fuca Electoral Area ca SpectaFcu le Lake e d it an ra STUDY Ju St AREA Morton Lake Sooke Lake Butchart Lake Devereux Sooke River Lake (Upper) Council Lake Lubbe Wrigglesworth Lake Lake MacDonald Goldstream Lake r Lake e iv R e k o Bear Creek o S Old Wolf Reservoir Boulder Lake Lake Mavis y w Lake H a G d Ranger Butler Lake o a l n d a s Lake Kapoor Regional N C t - r i a s Forslund Park Reserve e g n W a a a o m r l f C r a T Lake r e R e k C i v r W e e e r a k u g h C r e Mount Finlayson e k Sooke Hills Provincial Park Wilderness Regional Park Reserve G o ld s Jack t re a Lake m Tugwell Lake R iv e r W augh Creek Crabapple Lake Goldstream Provincial Park eek Cr S ugh o Wa o Peden k Sooke Potholes e Lake C R Regional Park h i v a e Sheilds Lake r r t e r k e s re C ne i R ary V k M e i v e r e r V C Sooke Hills Table of Significant Watersheds in the e d i t d c Wilderness Regional h o T Charters River C Park Reserve District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas r e e k Watershed Name Area (ha) Sooke Mountain Sooke River (Upper) 27114.93 Boneyard Provincial Park Lake DeMamiel Creek 3985.29 Veitch Creek 2620.78 -

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District by Sylvia Kenny University of Victoria, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences Co-op British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Prepared for the Capital Regional District, Victoria, B.C. December 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kenny, Sylvia. Aquifers of the Capital Regional District. Cover title. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-52651 1. Aquifers - British Columbia - Capital. 2. Groundwater - British Columbia - Capital. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. II. University of Victoria (B.C.). School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. III. Capital (B.C.) IV. Title. TD227.B7K46 2004 333.91’04’0971128 C2004-960175-X Executive summary This project focussed on the delineation and classification of developed aquifers within the Capital Regional District of British Columbia (CRD). The goal was to identify and map water-bearing unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers in the region, and to classify the mapped aquifers according to the methodology outlined in the B.C. Aquifer Classification System (Kreye and Wei, 1994). The project began in summer 2003 with the mapping and classification of aquifers in Sooke, and on the Saanich Peninsula. Aquifers in the remaining portion of the CRD including Victoria, Oak Bay, Esquimalt, View Royal, District of Highlands, the Western Communities, Metchosin and Port Renfrew were mapped and classified in summer 2004. The presence of unconsolidated deposits within the CRD is attributed to glacial activity within the region over the last 20,000 years. Glacial and glaciofluvial modification of the landscape has resulted in the presence of significant water bearing deposits, formed from the sands and gravels of Capilano Sediments, Quadra and Cowichan Head Formations. -

Sooke School District

my RD E T H Br p i W T F O L e id F . I t ount ESTOBY RD G le M R Regional l n O O H Tr D ail Trai H L . Ce A Regional T HO N ra SC D il . SC N TEANOOK B Francis / King Park Reserve I.R. A i RK a LAKE ER g RD. a Freeman King NO. 13 r a Nature Centre SAANICH R D. HERBATE Regional MILLST Lake C 19 e ail n r McKENZIE t e nnial T Creek LAKE SBO 13 Gol BEAR MOUNTAIN R ge School Board Office Hans Helgesen Elementary id E Park d R Mt. Finlayson VALLEY COURSE A Panhand Trail il M le ra T 390 Creek ie h g CO enz i District of Highlands cK Trail H Mine U M FAC 14 MALAHAT LAND DIST. N Municipal Office Facilities Happy Valley Elementary T Trail R H AN D. Regional S Park k Y IN R (RESTRICTED AREA) Park GOLDSTREAM LAND DIST. GTO ee N Cr C GH GATE MILLINGTON PL. rail H U . T L O T WO U E R rail O DANBY PL. Chow-Nicoll rail zie O B B HANBURYPL D LS HA T o en C IL D K C W G W Mc H Park n N. UGG KI ra N ra A E L PL S TRANS 15 PL . or PRIOR ig STONEHAVEN Transportation John Muir Elementary Y S i LYNBURNE PL. b PASSAGE 20 gflo fl T . AN . o ea O T RIVERS R w ON R S w C y o LAKE N e T I . -

Greater Victoria & Region Greater Victoria & Region

Galiano Island Greater Greater Mayne Victoria Island Salt Spring Island Saturna North Island & Region S Pender & Region D N A Island L S For more detailed I F L U 5 59 G maps, see pages 8– . D N A R South E V U Pender O C The Gulf Islands N Island A V O T Saanich Peninsula & Sidney Victoria, Saanich, Esquimalt & Oak Bay S A BC Ferries – WestShore, Colwood, Langford, Highlands, 1 NORTH Swartz Bay View Royal & Metchosin A SAANICH Ferry Terminal N I Sooke & Port Renfrew Mill C Bay H I TO SA N JUAN I N 2 SLA ND AND SIDNEY ANA T COR L Victoria TES LEGEND: R A Gulf Islands N E International S National Park - Airport C T Highway A Reserve N A D A Main Road UNITED STATES H W Y John Dean 17 Ferry Route . Provincial Sidney CANADA Park James Island Park Island CENTRAL Ferry Terminal Brentwood SAANICH Bay Island View Victoria Int’l Airport Beach Park P Full-Service Seaplane A M T R B Terminal A A S Y T N H W Helijet Terminal O R Y S Gowlland Tod . Y Provincial A A Mount Work I L Park Sooke T N Regional Elk I Lake F Park Lake 17A O 1 F HIGHLANDS Cordova Bay Beaver Elk/Beaver G Lake Lake E Regional O VIEW Park R ROYAL G N I Francis Mt. Douglas A King Park Regional Goldstream Thetis Lake Park SAANICH Provincial Regional Park Park University r 17 of Victoria e v i R Sooke Mount W E Potholes 1A WESTSHORE Tolmie Provincial Park Cadboro-Gyro Park LANGFORD Royal Roads VICTORIA Park . -

DIRECTIONS to SILVER SPRAY

SILVER SPRAY / SOOKEPOINT DIRECTIONS GPS setting: 1000 Silver Spray Drive, Sooke BC 39 Miles (63 Km/58 Minutes) From Swartz Bay Ferry Or The Airport: 1. Take Hwy# 17 (Patricia Bay Hwy.) South toward Victoria, but EXIT at McKenzie Rd. & Turn Right. 2. Follow McKenzie Rd. to Hwy# 1 (Trans Canada Highway) Turn Right (Westbound) 3. Drive West on Hwy# 1 - Stay in Right Lane 4. Take Colwood / Sooke Exit to Hwy# 14 (Old Island Hwy# 1A which joins Sooke Rd.) 5. Stay on Hwy# 14 past Colwood, Langford, Glen Lake & Metchosin 6. Watch on Right side for signs “Olde English Pub”, “Historic Pub” and “Beer & Wine off-sales”. 7. Immediately past this white Pub & Restaurant called the ‘17 Mile House’ TURN LEFT on Gillespie Road. Look for the SookePoint sign. 8. Follow Gillespie Road to EAST SOOKE and continue until the road ends in a T. 9. Look for the SookePoint sign and Turn Right onto EAST SOOKE ROAD. 10. Stay on East Sooke Road as the numbers increase past 7000 (Go to 7000 if lost) 11. Stay on paved road only until the end and turn LEFT onto Silver Spray Drive. You’ll see the big Silver Spray / SookePoint sign. 12. Follow Silver Spray Drive for more than a kilometer until you come to the second set of Granite Columns and SookePoint signs, 13. Follow the signs to the Parking Area to start the Tour. 26 Miles (42 Km/45 Minutes) From Downtown Victoria: 1. Take Douglas St. North (just 1 block from the Inner Harbour). 2. As Douglas St. -

2006 Minutes Combined

DISTRICT OF METCHOSIN MINUTES FOR THE COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS METCHOSIN MUNICIPAL HALL 4450 HAPPY VALLEY ROAD ON MONDAY, JANUARY 9, 2006, at 7:05 p.m. ___________________________________ Present: Mayor Ranns in the Chair; Councillors Gramigna, Kahakauwila, Mitchell and Webb. Also present were J. Lambie, CAO, and C. Clark, Recording Secretary. AGENDA, ADDITIONS & APPROVAL 06-01-09 Moved and Seconded by Councillors Kahakauwila and Mitchell: “That the agenda be approved as presented.” Carried PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Lund Eric Lund, Regional Director, Juan de Fuca Electoral Area on February 2005, East Sooke voted on amalgamation with Sooke, 75% said they wanted to stay rural Mr. Lund presented a petition with 432 signatures on it in favour of re-opening the study on amalgamation things have changed since the last time this was looked at total population is approximately 1,800 and 530 voted in the last election policing costs influenced the last study, that’s not an issue now there will be tax advantages from forests with us O’Connell Will O’Connell, 969 Kangaroo Road here to propose a dirt jump park found a new location beside the hedge bordering the parking lot of the firehall have a design for 3 jumps it will be safe Donaldson Brent Donaldson, 4039 Chalister Court concerned with the issue on page 12 regarding marketing boards is this driven from marketing boards which usually don’t support small farmers support the bike park suggested tonight Bolton Brian Bolton, 1091 Glen Forest Way support the bike jump -

City of Colwood Minutes of the Special Meeting of Council

CITY OF COLWOOD MINUTES OF THE SPECIAL MEETING OF COUNCIL Monday, January 5, 2000 at 7:00 p.m. 3300 Wishart Road, Colwood B.C. Council Chambers PRESENT Mayor Beth Gibson Councillors Hugh Bryce Gordie Logan Ernie Robertson Jody Twa ABSENT Councillors Scotty Davidson Jason Nault ATTENDING Chief Administrative Officer Joseph A. Calenda Municipal Engineer Gary Smirfitt Treasurer-Collector Selwyn Rose Municipal Planner Simon Lawrence 1. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA MOVED BY: COUNCILLOR BRYCE SECONDED: COUNCILLOR LOGAN That the agenda be approved as presented. CARRIED. 2. NEW BUSINESS A. TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE 1. RE: CONTRACT AWARD FOR CITY OF COLWOOD PHASE III AND A PORTION OF PHASE IV, GRAVITY TRUNK SEWER ON METCHOSIN ROAD (10.7.15) Referred from Regular Meeting of Council – December 20, 1999 Council again considered the report from the Municipal Engineer regarding the Contract Award for City of Colwood Phase III and a portion of Phase IV of the gravity trunk sewer on Metchosin Road. The report provided an overview of the process carried out in soliciting bids for the construction of a gravity trunk sewer on Metchosin Road, from the Fire Hall at Wishart Road to the upstream end near Farview Road. MOVED BY: COUNCILLOR TWA SECONDED: COUNCILLOR LOGAN That the contract between JJM Construction Ltd. and the City of Colwood, for a provision for a gravity trunk sewer on Metchosin Road (Phase III and a portion of Phase IV from the Fire Hall at Wishart Road to the upstream end near Farview Road), be approved and that the Mayor and Chief Administrative Officer be authorized to execute the agreement. -

Media Kit | Truekey.Ca

MEDIA KIT | TRUEKEY.CA SOOKEPOINT OCEAN COTTAGE RESORT IS SET AWAY FROM THE VILLAGE OF SOOKE ON POSSESSION POINT, THE MOST SOUTHWEST TIP OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’S VANCOUVER ISLAND. THIS PREMIUM LUXURY RESORT IS SURROUNDED BY NATURE – PERCHED CLIFFSIDE ABOVE THE PACIFIC OCEAN AND HUGGED BY THE FORESTED LANDS OF THE POINT. This is your destination for unparalleled and abundant Orca whales and other ocean life watching opportunities right from your suite; plus you’re conveniently located near world class fishing charters in Sooke, endless scenic hikes and trails, sea kayaking, biking and more. SookePoint Ocean Cottage Resort’s oceanside suites offer an unrivaled oceanic vacation experience. An ideal home base for any traveler, each beautifully fully furnished studio, 1 and 2 bedroom suites offer breathtaking and undisturbed ocean views, fully equipped gourmet kitchens and overhanging ocean decks. MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] 403.614.6175 FACTS • The Resort offers 14 fully furnished, fully equipped studio, 1 and 2 bedroom vacation homes with incredible panoramic ocean views (more suites coming soon)! • Currently under development, the resort’s future amenities will include a pool, spa, marina, whale research centre, shops, restaurants, and more! • SookePoint Resort is located beside East Sooke Park which offers many hikes and hidden beaches. The village of Sooke is only 30 minutes away along with many other Sooke adventures. LINKS Website: www.sookepointresort.ca @SookePointResort Email: [email protected] @SookePointResort Trip Advisor: SookePoint Ocean Cottage Resort MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] 403.614.6175 ACTIVITIES || TRUEKTRUEKEEY.CA FISHING CHARTERS Experience the thrill of reeling in a 40-50 lb. -

Katharine Dickerson

Katharine Dickerson 5315 Highway 6, New Denver, BC. V0G 1S1 Phone: 250-358-2427 email: [email protected] Born: Duluth Minnesota 1947 Canadian Citizen 1977 Education 2005 “Oriental Carpets” Workshop/lecture by Dr. John Thompson, Oxford University, given by the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta 1995 Studied Maori flax twining with Edward Maxwell, Whakatane, New Zealand 1984 “Introduction to Computer Programming”, Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, Calgary 1969-70 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illionois 1969 summer Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine 1968-69 New York Crafts Student’s League, New York, New York 1968 summer Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine 1966-68 University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 1966 summer University of Minnesota, Duluth, Minnesota 1965-66 Denison University, Granville, Ohio Professional 2011 2 day workshop “Fantastic Flesberg” & lecture on my work, Weaver’s Guild, Grand Forks, B.C. 2010 2 day workshop “Colour usage with tabby” & lecture on my work, Weaver’s Guild, Victoria, B.C. 2010 2 day workshop “Fantastic Flesberg” & lecture on my work and Salish twining, Weaver’s Guild, Salt Spring Island 2009-present Valhalla School of Fine Arts, Board member and Treasurer 2009-2011 Slocan Lake Gallery Society, Board member and Treasurer 2009 Appointed “Lecturer Emeritus” by the Alberta College of Art + Design Board of Governors 1977-2007 Lecturer and Administrative duties in Fibre/Textiles programme, Fine Arts Department, Alberta College of Art + Deign 2005 Presenter and Workshop leader, Norwegian Textile Conference, Vesterheim Museum, Decorah, Iowa 2005 Guest lecturer, Textiles, Art History and Graduate Studies Departments, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University, Halifax, Nova Scotia 2003 Interpreter of Contemporary Textiles, Vesterheim American Norwegian Textile tour of Norway 2001 Moderator, Beyond Boarders, Craft Marketing Conference, Nelson, B.C. -

FACING HOMELESSNESS Greater Victoria Report on Housing & Supports 2012/13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“There's not enough housing for everybody" - Montana FACING HOMELESSNESS Greater Victoria Report on Housing & Supports 2012/13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHORS: Bernie Pauly, RN, Ph.D, Centre for Addictions Research of BC and School of Nursing, University of Victoria Geoff Cross, MA candidate, Centre for Addictions Research of BC, University of Victoria Kate Vallance, MA, Centre for Addictions Research of BC, University of Victoria Andrew Wynn-Williams, MA, Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness Kelsi Stiles, Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessnes THANK YOU TO EVERYONE WHO HELPED WITH THIS REPORT: Aleck Ostry (University of Victoria), Derek Book (Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness), Diana Stapleton (Food Banks Canada), Don Van Wart (Ministry of Social Development and Social Innovation), Elizabeth Tang (Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation), Etienne Pinel (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation), Hannah Rabinovitch (Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness), Helma Libick (Victoria Cool Aid Society), Jenn Mortimer (Beacon Community Services), Jill Atkey (BC Non-Profit Housing Association), Joann Connolly (Victoria Cool Aid Society), Lance Jakubec (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation), Lynn L. Bourgon (Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Marika Albert (Community Social Planning Council of Greater Victoria), Melanie Kurrein (Provincial Health Services Authority), Randy Sarju (BC Housing), Rebecca Siggner (BC Housing), Richard Gabay (Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation), Sonya Kupka (Dieticians