A Case Study Exploring a Women's and Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Vop #141 / 3 Are on My Own Recommended Reading List, So I Ordered the Following Books

Visions of Paradise #141 Visions of Paradise #141 Contents Out of the Depths...............................................................................................page 3 Favorite SF Movies ... Paperback Swap Will F. Jenkins Day..............................................................................................page 4 A celebration of the life and career of Murray Leinster The Passing Scene................................................................................................page 6 Homes ... May 2009 Wondrous Stories................................................................................................page 9 Going For Infinity … F&SF ... Deathworld ... Heat On the Lighter Side............................................................................................page 13 _\\|//_ ( 0_0 ) ___________________o00__(_)__00o_________________ Robert Michael Sabella E-mail [email protected] Personal blog: http://adamosf.blogspot.com/ Sfnal blog: http://visionsofparadise.blogspot.com/ Fiction blog: http://bobsabella.livejournal.com/ Available online at http://efanzines.com/ Copyright ©May 2009, by Gradient Press Available for trade, letter of comment or request Artwork Franz H. Miklis … Cover Terry Jeeves … p. 9 http://www.sfsite.com/~silverag/leinster.html … page 4 Out of The Depths I am not a huge movie fan, partly because I don’t have a lot of available time to watch them (without depleting my limited reading time), and partly because movies rarely interest me as much as a good book does. So when I was -

Realms of Fantasy Dec 2010

The WyndMaster's Lady The WyndMaster's Son Srae Iss-Ka-Mala A Dream of Drowned Hollow Nexus Point Motor City Fae Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Chaeya Author: Lee Barwood Author: Jaleta Clegg Author: Cindy Spencer Pape www.windlegends.org www.windlegends.org www.electricgentlemen.com www.leebarwood.com www.jaletac.com www.cindyspencerpape.com Background Images Courtesy Of: © 2010 STScI & NASA Bloodsworn: Bound by Magic Mudflat Spice and Sorcery Blood of the Dark Moon A Bloody Good Cruise Author: Kathy Lane Author: Phoebe Matthews Author: Adrianne Brennan Author: Diana Rubino www.kyrlane.com www.phoebematthews.com www.adriannebrennan.com www.dianarubino.com Resurrection Code Second Night: More Fairy Tales Retold Some Cost a Passing Bell On the Wild Side Heartstone Shadows of the Soul Author: Lyda Morehouse Author: Caroline Aubrey Author: Lee Barwood Author: Gerri Bowen Author: Lynda K. Scott Author: Angelique Armae www.lydamorehouse.com www.carolineaubrey.net www.leebarwood.com www.gerribowen.com www.lyndakscott.com www.angeliquearmae.com INFINITE WORLDS OF FANTASY AUTHORS IMAGINATION UNRESTRICTED BY REALITY The WyndMaster's Lady The WyndMaster's Son Srae Iss-Ka-Mala A Dream of Drowned Hollow Nexus Point Motor City Fae Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Charlotte Boyett~Compo Author: Chaeya Author: Lee Barwood Author: Jaleta Clegg Author: Cindy Spencer Pape www.windlegends.org www.windlegends.org www.electricgentlemen.com www.leebarwood.com www.jaletac.com www.cindyspencerpape.com Background Images -

SF Commentary 97

SSFF CCoommmmeennttaarryy 9977 112233 ppaaggeess AAuugguusstt 22001188 AWARDS ION NEWCOMBE: EDWINA HARVEY WINS A. BERTRAM CHANDLER AWARD 2018 EDWINA TELLS HER STORY TRIBUTES TO LUCY ZINKIEWICZ SHELBY VICK GARDNER DOZOIS HARLAN ELLISON NEW BOOKS COLIN STEELE BEST OF 2016 & 2017 BRUCE GILLESPIE JENNIFER BRYCE IAN MOND DOUG BARBOUR Cover: Stephen Campbell: ‘Dear Diary’. S F Commentary 97 August 2018 123 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 97, August 2018, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Available only from eFanzines.com: Portrait edition (print page equivalent) at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC97P.pdf or Landscape edition (widescreen): at http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC97L.pdf or from my email address: [email protected] All correspondence: [email protected]. Member fwa. Front cover: Stephen Campbell: ‘Dear Diary’. Back cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ’Jewelled Landscape’. Photographs: Nigel Rowe (p. 6); Graeme Batho (p. 7); Ion Newcombe (p. 10); James ’Jocko’ Allen (p. 16); Nicole Neenan (p. 21). 2 Contents 4 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS 20 THE FIELD Bruce Gillespie Colin Steele 7 EDWINA HARVEY WINS THE 2018 46 THE BEST OF EVERYTHING, 2016 A. BERTRAM CHANDLER AWARD 63 Ion Newcombe, THE BEST OF EVERYTHING, 2017 for the Australian Science Fiction Foundation Bruce Gillespie 9 THE A. BERTRAM CHANDLER AWARD: 79 THE THREE BEST BOOKS AND CONCERTS WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND FOR 2016 Edwina Harvey 85 THE THREE BEST BOOKS AND CONCERTS FOR 2017 16 VALE LUCY ZINKIEWICZ Jennifer Bryce Edwina Harvey 91 MY TOP BOOKS FOR 2017 17 TRIBUTES TO: Ian Mond SHELBY VICK (1928–2018) GARDNER DOZOIS (1947–2018) HARLAN ELLISON (1934–2018) 96 TOP SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY Bruce Gillespie BOOKS OF 2016 Douglas Barbour 3 I must be talking to my friends Unkindest cut First there was SF Commentary 96. -

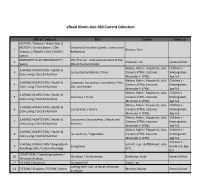

Eread Illinois Axis 360 Current Collection

eRead Illinois Axis 360 Current Collection BISAC Subject Title Author Audience HISTORY / Military / World War II; HISTORY / United States / 20th Greatest Generation Speaks : Letters and 1 Brokaw, Tom Century; LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Reflections Letters BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Into Thin Air : A Personal Account of the 2 Krakauer, Jon General Adult Sports Mount Everest Diaster Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & 3 Los productos lßcteos / Dairy Cisneros (TRN); Castaner, Kindergarten, Daily Living / Diet & Nutrition Mercedes P. (TRN) Age 5-6 Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & Las grasas, los aceites, y los dulces / Fats, 4 Cisneros (TRN); Castaner, Kindergarten, Daily Living / Diet & Nutrition Oils, and Sweets Mercedes P. (TRN) Age 5-6 Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & 5 Las frutas / Fruits Cisneros (TRN); Castaner, Kindergarten, Daily Living / Diet & Nutrition Mercedes P. (TRN) Age 5-6 Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & 6 Los cereales / Grains Cisneros (TRN); Castaner, Kindergarten, Daily Living / Diet & Nutrition Mercedes P. (TRN) Age 5-6 Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & Las carnes y las protefnas / Meats and 7 Cisneros (TRN); Castaner, Kindergarten, Daily Living / Diet & Nutrition Proteins Mercedes P. (TRN) Age 5-6 Nelson, Robin ; Fitzpatrick, Julia Children's - JUVENILE NONFICTION / Health & 8 Las verduras / Vegetables -

Isaac Asimov Presents the Golden Years of Science Fiction Sixth Series Edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H

Isaac Asimov Presents The Golden Years of Science Fiction Sixth Series Edited By Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg CONTENTS Foreword Introduction THE RED QUEEN’S RACE Isaac Asimov FLAW John D. MacDonald PRIVATE EYE Lewis Padgett MANNA Peter Phillips THE PRISONER IN THE SKULL Lewis Padgett ALIEN EARTH Edmond Hamilton HISTORY LESSON Arthur C. Clarke ETERNITY LOST Clifford D. Simak THE ONLY THING WE LEARN C.M. Kornbluth PRIVATE—KEEP OUT Philip MacDonald THE HURKLE IS A HAPPY BEAST Theodore Sturgeon KALEIDOSCOPE Ray Bradbury DEFENSE MECHANISM Katherine MacLean COLD WAR Harry Kuttner THE WITCHES OF KARRES James H. Schmitz NOT WITH A BANG Damon Knight SPECTATOR SPORT John D. MacDonald THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS Ray Bradbury DEAR DEVIL Eric Frank Russell SCANNERS LIVE IN VAIN Cordwainer Smith BORN OF MAN AND WOMAN Richard Matheson THE LITTLE BLACK BAG C.M. Kornbluth ENCHANTED VILLAGE A.E. van Vogt ODDY AND ID Alfred Bester THE SACK William Morrison THE SILLY SEASON C.M. Kornbluth MISBEGOTTEN MISSIONARY Isaac Asimov TO SERVE MAN Damon Knight COMING ATTRACTION Fritz Leiber A SUBWAY NAMED MOBIUS A.J. Deutsch PROCESS A.E. van Vogt THE MINDWORM C.M. Kornbluth THE NEW REALITY Charles L. Harness Foreword The years 1949 and 1950 saw into print some of the best science fiction ever written. The technology and the fears brought about by the atomic age pressed new horizons and the concept of absolute mortality upon the world, and it was through this most disturbing vision that the science fiction giants finally found their wings. In this, the sixth volume in the highly acclaimed series of anthologies edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. -

Science Fiction Review 33 Geis 1979-11

SCIENCE NUMBER 33 $1.75 FICTION REVIEW Interview CHARLES SHEFFIELD A WRITER'S NATURAL ENEMY EDITORS BY GEORGE R. R. MARTIN NOISE LEVEL By John Brunner YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD BY ORSON SCOTT CARD Darrell Schweitzer Elton T. Elliott NEWS CARTOONS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ISSN “ Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. BOX 11408 NOVEMBER 1979 -- VOL.8 NO.5 WHOLE NUMBER 33 PORTLAND, OR 97211 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS., editor & publisher PAULETTE, SPECIAL ASSISTANT COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 REVIEWS— SINGLE COPY --- $1.75 WAR OF THE WORLDS (RECORD)........19 INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES SHEFFIELD. .10 ONCE UPON A TIME (RECORD)......... 19 CONDUCTED BY KARL T. PFLOCK SCREAMS OF A WINTER NIGHT (MOVIE).20 THE OUTCASTS OF HEAVEN BELT (BOOK) BEYOND ATLANTIS (MOVIE)..........20 INSIDE—OUTSIDE (BOOK).... ...... QUEST OF THE THREE WORLDS (BOOK).. HE HEARS.... HALLOWEEN (MOVIE)................ 20 THE BROOD (MOVIE)................ 20 THE WORLD IS ROUND (BOOK)....... RECORD REVIEWS THE INTELLIGENCE AGENTS (BOOK).... BY STEVEN E. MCDONALD............. 19 SUPERMAN (MOVIE)................. 20 CIRCLE OF IRON (MOVIE)........... 20 ANALOG YEARBOOK (BOOK)............ THE MUPPET MOVIE (MOVIE).........21 ALIEN WORLDS (BOOK).............. BEASTS OF GOR (BOOK),............. AND THEN I SAW.... DRACULA (MOVIE).................. 21 MOVIE AND TELEVISION REVIEWS PHANTASM (MOVIE)................. 21 SPACE PIRATES QoOK)............. BY THE EDITOR......................20 THE AMITYVILLE HORROR (MOVIE).... 21 MACROLIFE (BOOK)................. PROPHESY (MOVIE)................. 21 THE CAVE OF TIME (BOOK)........... MOONRAKER (MOVIE)................ 22 THE TIME TRIP (BOOK)............. A WRITER'S NATURAL ENEMY: EDITORS JANISSARIES (BOOK),.............. BY GEORGE R.R. MARTIN............. 28 UP FROM THE DEPTHS (MOVIE)...... 72. -

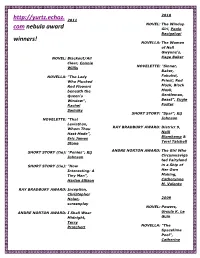

Com Nebula Award Winners! -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

2010 http://yurtz.echoz. 2011 NOVEL: The Windup com nebula award Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi winners! NOVELLA: The Women of Nell Gwynne's, NOVEL: Blackout/All Kage Baker Clear, Connie NOVELETTE: "Sinner, Willis Baker, NOVELLA: "The Lady Fabulist, Who Plucked Priest; Red Red Flowers Mask, Black beneath the Mask, Queen's Gentleman, Window", Beast", Eugie Rachel Foster Swirsky SHORT STORY: "Spar", Kij NOVELETTE: "That Johnson Leviathan, RAY BRADBURY AWARD: District 9, Whom Thou Neill Hast Made", Blomkamp & Eric James Terri Tatchell Stone ANDRE NORTON AWARD: The Girl Who SHORT STORY (tie): "Ponies", Kij Circumnaviga Johnson ted Fairyland SHORT STORY (tie): "How in a Ship of Interesting: A Her Own Tiny Man", Making, Harlan Ellison Catherynne M. Valente RAY BRADBURY AWARD: Inception, Christopher Nolan, 2009 screenplay NOVEL: Powers, ANDRE NORTON AWARD: I Shall Wear Ursula K. Le Midnight, Guin Terry NOVELLA: "The Pratchett Spacetime Pool", Catherine Asaro ANDRE NORTON AWARD: Harry Potter and the NOVELETTE: "Pride and Deathly Prometheus", Hallows, J. K. John Kessel Rowling SHORT STORY: "Trophy Wives", Nina 2007 Kiriki Hoffman NOVEL: Seeker, Jack McDevitt SCRIPT: WALL-E, Andrew NOVELLA: Burn, James Stanton, Jim Patrick Kelly Reardon & Peter Docter NOVELETTE: "Two Hearts", Peter S. ANDRE NORTON AWARD: Flora's Dare, Beagle Ysabeau S. Wilce SHORT STORY: "Echo", Elizabeth Hand 2008 SCRIPT: Howl's NOVEL: The Yiddish Moving Policemen's Castle, Hayao Union, Miyazaki, Michael Cindy Davis Chabon Hewitt & Donald H. NOVELLA: "Fountain of Hewitt Age", Nancy Kress -

Theory and Interpretation of Narrative James Phelan and Peter J

Theory and InTerpreTation of narrative James phelan and peter J. rabinowitz, Series editors Narrative StructureS and the LaNguage of the SeLf Matthew Clark T h e o h I o S T a T e U n I v e r sit y p r e ss • C o l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Matthew, 1948– Narrative structures and the language of the self / Matthew Clark. p. cm.—(Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1128-1 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9227-3 (cd) 1. Self in literature. 2. Self (Philosophy) in literature. 3. Subject (Philosophy) in literature. 4. Subjectivity in literature. 5. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Title. II. Series: Theory and interpretation of narrative series. PN56.S46C57 2010 809'.93384—dc22 2010023781 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1128-1) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9227-3) Cover design by Fulcrum Creatives, LLC Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 C o n T e n ts Acknowledgments vii Introduction The Self and Narrative 1 Part One PhiLoSoPhicaL fabLeS of the SeLf Chapter 1 The Reflexive Self: Descartes and Ovid 13 Chapter 2 The Furniture of the Self: Montaigne, Highsmith, Dostoevsky 27