Nietzsche on Objects Justin Remhof Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 6 Article 3 Issue 2 The New Legal Realism at Ten Years 6-2016 Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth Elizabeth Mertz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Bryant Garth & Elizabeth Mertz, Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond, 6 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 121 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol6/iss2/3 This Foreword is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. Garth & Mertz UPDATED 4.14.17 (Do Not Delete) 4/19/2017 9:40 AM Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth* and Elizabeth Mertz** I. Celebrating Ten Years of New Legal Realism ........................................................ 121 II. A Developing Tradition ............................................................................................ 124 III. Current Realist Directions: The Symposium Articles ....................................... 131 Conclusion: Moving Forward ....................................................................................... 134 I. CELEBRATING TEN YEARS OF NEW LEGAL REALISM This symposium commemorates the tenth year that a body of research has formally flown under the banner of New Legal Realism (NLR).1 We are very pleased * Chancellor’s Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law; American Bar Foundation, Director Emeritus. ** Research Faculty, American Bar Foundation; John and Rylla Bosshard Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Many thanks are owed to Frances Tung for her help in overseeing part of the original Tenth Anniversary NLR conference, as well as in putting together some aspects of this Symposium. -

Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: a Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: A Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES DISTINGUISHING SCIENCE FROM PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF THOMAS NAGEL’S RECOMMENDATION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION By MELISSA LAMMEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Melissa Lammey defended this dissertation on February 10, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Ruse Professor Directing Dissertation Sherry Southerland University Representative Justin Leiber Committee Member Piers Rawling Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Warren & Irene Wilson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the contributions of Michael Ruse to my academic development. Without his direction, this dissertation would not have been possible and I am indebted to him for his patience, persistence, and guidance. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Sherry Southerland in helping me to learn more about science and science education and for her guidance throughout this project. In addition, I am grateful to Piers Rawling and Justin Leiber for their service on my committee. I would like to thank Stephen Konscol for his vital and continuing support. -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

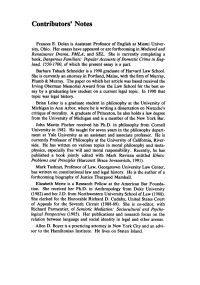

Contributors' Notes

Contributors' Notes Frances E. Dolan is Assistant Professor of English at Miami Univer- sity, Ohio. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Medieval and Renaissance Drama, PMLA, and SEL. She is currently completing a book, DangerousFamiliars: PopularAccounts of Domestic Crime in Eng- land, 1550-1700, of which the present essay is a part. Barbara Taback Schneider is a 1990 graduate of Harvard Law School. She is currently an attorney in Portland, Maine, with the firm of Murray, Plumb & Murray. The paper on which her article was based received the Irving Oberman Memorial Award from the Law School for the best es- say by a graduating law student on a current legal topic. In 1990 that topic was legal history. Brian Leiter is a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he is writing a dissertation on Nietzche's critique of morality. A graduate of Princeton, he also holds a law degree from the University of Michigan and is a member of the New York Bar. John Martin Fischer received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell University in 1982. He taught for seven years in the philosophy depart- ment at Yale University as an assistant and associate professor. He is currently Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, River- side. He has written on various topics in moral philosophy and meta- physics, especially free will and moral responsibility. Recently, he has published a book jointly edited with Mark Ravizza entitled Ethics: Problems and Principles (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991). Mark Tushnet, Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, has written on constitutional law and legal history. -

Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist?

BROPHY.FINAL.OC (DO NOT DELETE) 12/18/2013 9:48 AM Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist? BEYOND THE FORMALIST-REALIST DIVIDE: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN JUDGING. By Brian Z. Tamanaha. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2010. 252 pages. $24.95. Reviewed by Alfred L. Brophy* In Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide, Brian Tamanaha seeks to rewrite the story of the differences between the age of formalism and the age of legal realism. In essence, Tamanaha thinks there never was an age of formalism. For he sees legal thought even in the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—what is commonly known as the age of formalism1—as embracing what he terms “balanced realism.”2 Legal history3 and jurisprudence4 both make important use of that divide, or, to use somewhat less dramatic language, the shift from formalism (known often as classical legal thought) to realism. Moreover, as Tamanaha describes it, recent studies of judicial behavior that model the extent to which judges are formalist—that is, the extent to which they apply the law in some neutral fashion or, conversely, recognize the centrality of politics to * Judge John J. Parker Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina. I would like to thank Michael Deane, Arthur G. LeFrancois, Brian Leiter, David Rabban, Dana Remus, Stephen Siegel, and William Wiecek for help with this. 1. See, e.g., MORTON J. HORWITZ, THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960, at 16–18 (1992) [hereinafter HORWITZ, TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960] (discussing formalism, generally); MORTON J. -

Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (Reviewing G

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2002 Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000)) Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000))," 54 Stanford Law Review 1129 (2002). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory Brian Leiter* IF YOU'RE AN EGALITARIAN, How COME YOU'RE SO RICH? By G. A. Cohen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000. 237 pp. $18.00. I. INTRODUCTION G. A. Cohen, the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at Oxford, first came to international prominence with his impressive 1978 book on Marx's historical materialism,1 a volume which gave birth to "analytical Marxism."'2 Analytical Marxists reformulated, criticized, and tried to salvage central features of Marx's theories of history, ideology, politics, and economics. They did so not only by bringing a welcome argumentative rigor and clarity to the exposition of Marx's ideas, but also by purging Marxist thinking of what we may call its "Hegelian hangover," that is, its (sometimes tacit) commitment to Hegelian assumptions about matters of both philosophical substance and method. -

Law School News

LAW SCHOOL NEWS Volume 12, No. 25 November 6, 2002 View Past Issues FACULTY WRITINGS Kimberlee Kovach, Ethics for Whom? The Recognition of Diversity in Lawyering: Calls for Plurality in Ethical Considerations and Rules of Representational Work, IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION ETHICS: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE 57 (Phyllis Bernard & Bryant Garth eds.; Washington, D.C.: American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution, 2002) Kimberlee Kovach, Enforcement of Ethics in Mediation, IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION ETHICS: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE 111 (Phyllis Bernard & Bryant Garth eds.; Washington, D.C.: American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution, 2002) Douglas Laycock, Debate 2: Should the Government Provide Financial Support for Religious Institutions That Offer Faith-Based Social Services?, 3 RUTGERS JOURNAL OF LAW & RELIGION No. 5 (2001-2002) (with Louis H. Pollack, Glen A. Tobias, Erwin Chemerinsky, Barry W. Lynn, & Nathan J. Diament). Douglas Laycock, Injudicious: Liberals Should Get Tough on Bush's Conservative Judicial Nominees - And Stop Opposing Michael McConnell, THE AMERICAN PROSPECT ONLINE, Oct. 30, 2002, http://www.prospect.org/webfeatures/2002/10/laycock-d-10-30.html. Brian Leiter, The Fate of Genius, TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT, Oct. 18, 2002, at 12 (reviewing Zarathustra's Secret: The Interior Life of Friedrich Nietzsche, by Joachim Köhler; Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography, by Rüdiger Safranski; and The Legend of Nietzsche's Syphilis, by Richard Schain). Ronald Mann, Credit Cards and Debit Cards in the United States and Japan, 55 VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW 1055 (2002). Jane Stapleton, Lords a'Leaping Evidentiary Gaps, 10 TORTS LAW JOURNAL 276 (2002). FACULTY ACTIVITIES Lynn Baker spoke on "Professional Responsibility: Critical Mass Tort Settlement Considerations" at the Third Annual Class Action/Mass Tort Symposium held by the Louisiana State Bar Association in New Orleans, Oct. -

Zarathustra's Metaethics

Canadian Journal of Philosophy ISSN: 0045-5091 (Print) 1911-0820 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcjp20 Zarathustra’s metaethics Neil Sinhababu To cite this article: Neil Sinhababu (2015) Zarathustra’s metaethics, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 45:3, 278-299, DOI: 10.1080/00455091.2015.1073576 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00455091.2015.1073576 Published online: 09 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 50 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcjp20 Download by: [NUS National University of Singapore] Date: 13 November 2015, At: 04:45 Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 2015 Vol. 45, No. 3, 278–299, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00455091.2015.1073576 Zarathustra’s metaethics Neil Sinhababu* Department of Philosophy, National University of Singapore, 3 Arts Link, Singapore 117570, Singapore (Received 29 October 2014; accepted 14 July 2015) Nietzsche takes moral judgments to be false beliefs, and encourages us to pursue subjective nonmoral value arising from our passions. His view that strong and unified passions make one virtuous is mathematically derivable from this subjectivism and a conceptual analysis of virtue, explaining his evaluations of character and the nature of the Overman. Keywords: Nietzsche; Zarathustra; metaethics; virtue; subjectivism; Overman Friedrich Nietzsche may be the most forceful critic of morality in all of philos- ophy. Yet he often ascribes value to actions, characters, and ways of life. How are these evaluative claims consistent with his rejection of morality? This paper argues that while Nietzsche regards moral judgments as false beliefs, he sees passions as making their objects subjectively valuable in a nonmoral way. -

Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings

SMU Law Review Volume 60 Issue 2 Article 6 2007 Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings Theodore P. Seto Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Theodore P. Seto, Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings, 60 SMU L. REV. 493 (2007) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol60/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. UNDERSTANDING THE U.S. NEws LAW SCHOOL RANKINGS Theodore P. Seto* UCH has been written on whether law schools can or should be ranked and on the U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT ("U.S. NEWS") rankings in particular.' Indeed, in 1997, one hundred *Professor, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. The author is very grateful for the comments, too numerous to mention, given in response to his SSRN postings. He wants to give particular thanks to his wife, Professor Sande Buhai, for her patience in bearing with the unique agonies of numerical analysis. 1. See, e.g., Michael Ariens, Law School Brandingand the Future of Legal Education, 34 ST. MARY'S L. J. 301 (2003); Arthur Austin, The Postmodern Buzz in Law School Rank- ings, 27 VT. L. REv. 49 (2002); Scott Baker et al., The Rat Race as an Information-Forcing Device, 81 IND. L. J. 53 (2006); Mitchell Berger, Why the U.S. News & World Report Law School Rankings Are Both Useful and Important, 51 J. -

Explaining Theoretical Disagreement

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Explaining Theoretical Disagreement Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Explaining Theoretical Disagreement," 76 University of Chicago Law Review 1215 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Explaining Theoretical Disagreement Brian Leitert Scott Shapiro has recently argued that Ronald Dworkin posed a new objection to legal positivism in Law's Empire, to which positivists, he says, have not adequately re- sponded. Positivists,the objection goes, have no satisfactory account of what Dworkin calls "theoreticaldisagreement" about law, that is, disagreement about "the grounds of law" or what positivists would call the criteriaof legal validity. I agree with Shapiro that the critique is new but disagree that it has not been met. Positivism cannot offer an ex- planation that preserves the "Face Value" of theoretical disagreements,because the only intelligible dispute about the criteria of legal validity is an empirical or "head count" dispute, that is, a dispute about what judges are doing, and how many of them are doing it (since it is the actual practice of officials and their attitudes towards -

Positivism, Formalism, Realism

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1999 Positivism, Formalism, Realism Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Positivism, Formalism, Realism ," 99 Columbia Law Review [v] (1999). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY POSITIVISM, FORMALISM, REALISM LEGAL POSITIVISM IN AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE. By Anthony Sebok.* New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Pp. 327. $59.95. Reviewed by Brian Leiter" In Legal Positivism in American Jurisprudence, Anthony Sebok traces the historical and philosophical relationship between legal positivism and the dominant schools of American jurisprudence: Formalism, Realism, Legal Process, and FundamentalRights. Sebok argues that formalism fol- lowed from the central tenets of ClassicalPositivism, and that both schools of thought were discredited-throughmisunderstandings-during the Realist period. Positivism'sessential tenets were reassertedby Legal Process scholars, though soon thereafter misappropriatedby politically conservative theorists. In the concluding chapters of the book, Sebok argues that the recent theory known as "Soft" Positivism or "Incorporationism" holds out the possibility of redeeming the liberalpolitical credentials of positivism. In this Review Essay, ProfessorLeiter questions Sebok's jurisprudential analysis. In PartI, Leiter sets forth the central tenets ofpositivism, formal- ism, and realism. In PartII, he critiques each step in Sebok's jurispruden- tial argument. He shows thatformalism has no conceptual connection with positivism, while realism is essentially predicatedon a positivist conception of law. -

The Vietnam Draft Cases and the Pro-Religion Equality Project

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 43 Article 2 Issue 1 Spring 2014 2014 The ietnV am Draft aC ses and the Pro-Religion Equality Project Bruce Ledewitz Duquesne University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Ledewitz, Bruce (2014) "The ieV tnam Draft asC es and the Pro-Religion Equality Project," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 43: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol43/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIETNAM DRAFT CASES AND THE PRO-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT Bruce Ledewitz* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... ! II. WHY TOLERATE RELIGION? ............................................... 5 III. THE ANTI-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT IN CONTEXT ............................................................................... l6 IV. EVALUATING LEITER'S PROJECT ................................... 30 V. THE PRO-RELIGION EQUALITY PROJECT ...................... 38 VI. THE VIETNAM DRAFT CASES .......................................... .47 VII. THE LIMITATIONS OF CONSCIENCE CLAUSES ............ 61 VIII.