Why Was There No Public Inquiry Into the Lac-Mégantic Disaster? Mark Winfield York University June 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEG Magazine

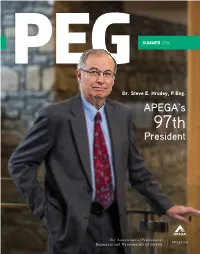

SUMMER 2016 Dr. Steve E. Hrudey, P.Eng. APEGA's 97th President The Association of Professional apega.ca Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta | WE SPECIALIZE IN SIMPLE, COST-EFFECTIVE AND RELIABLE FACILITY DESIGNS. Gold-plated designs are out of place under any market conditions. That’s why we focus on JVZ[LɈLJ[P]LLUNPULLYPUN[OH[ZPTWSPÄLZMHJPSP[`VWLYH[PVUZHUKTHPU[LUHUJL>LZ[YLHTSPUL LX\PWTLU[HUKKLZPNUZWLJPÄJH[PVUZ[VYLTV]LJVZ[S`V]LYKLZPNUHUKTPUPTPaLJVTWSL_P[` Put our experience to work for your project. Learn more at vistaprojects.com Contents PEG FEATURED PHOTO: SUMMER 2016 PAGE 10›› 34 52 68 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 8 & 9 New Council, Summit Recipients 4 President's Notebook 65 Viewfinder 10 Meet the President 6 Interim CEO’s Message 72 AEF Campaign Connection 15 Council Nominations Begin 20 Movers & Shakers 75 Focal Point 40 What’s Next in Legislative Review? 34 Professional Development 82 Member Benefits 49 All About apega.ca 52 Good Works 84 Record 68 Science Plus Youth Equals This 60 And You Are COVER PHOTO: Kurtis Kristianson, Spindrift Photography PRINTED IN CANADA SUMMER 2016 PEG | 1 US POSTMASTER: PEG (ISSN 1923-0044) is published quarterly in Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter, by the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta, c/o US Agent-Transborder Mail 4708 Caldwell Rd E, Edgewood, WA 98372-9221. $15 of the annual membership dues applies to the yearly subscription of The PEG. Periodicals postage paid at Puyallup, WA, and at additional mailing offices. US POSTMASTER, send address changes to PEG c/o Transborder Mail, PO Box 6016, Federal Way, WA 98063-6016, USA. -

Why Buildings Fail: Are We Learning from Our Mistakes?

Buildings 2012, 2, 326-331; doi:10.3390/buildings2030326 OPEN ACCESS buildings ISSN 2075-5309 www.mdpi.com/journal/buildings/ Editorial Why Buildings Fail: Are We Learning From Our Mistakes? M. Kevin Parfitt Department of Architectural Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +1 814 863 3244; Fax: +1 814 863 4789 Received: 30 August 2012 / Accepted: 31 August 2012 / Published: 5 September 2012 1. Introduction Most building professionals have investigated or performed remedial designs for at least one architectural or engineering system failure during their careers. Other practitioners, especially those who work for forensic consultants or firms specializing in disaster response and repair, are more familiar with the variety and extent of building failures as they assist their clients in restoring damaged or deficient buildings. The advent of social medial and twenty-four-hour news channels along with the general ease of finding more examples of failures in the Internet have made us realize that building failures in the broad sense are much more common than we may have realized. Relatively recent events leading to building failures such as the Christchurch, New Zealand earthquakes, the roof/parking deck of the Algo Centre mall in the northern Ontario, Canada city of Elliot Lake and the Indiana State Fairground stage collapse in the US are just a few reminders that much more work needs to be done on a variety of fronts to prevent building failures from a life safety standpoint. The need is compounded by economic concerns from what would be considered more mundane or common failures. -

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Executive Summary The Honourable Paul R. Bélanger Commissioner Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Executive Summary The Honourable Paul R. Bélanger Commissioner The Report consists of three volumes: 1. The Events Leading to the Collapse of the Algo Centre Mall; 2. The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process; and 3. Executive Summary. Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General ISBN 978-1-4606-4566-6 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-4606-4565-9 (Print) © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2014 Recycled paper THE ELLIOT LAKE LA COMMISSION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY D'ENQUETE ELLIOT LAKE The Honourable Paul R. Bélanger, L'honorable Paul R. Bélanger, Commissioner Commissaire October 15, 2014 The Honourable Madeleine Meilleur Attorney General of Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General 720 Bay Street, 11th Floor Toronto, ON M5G 2K1 Dear Madam Attorney, I am pleased to deliver to you the Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry in both its English and French versions, as required by the Order in Council creating the Inquiry. Part One examines the events leading up to the collapse of the Algo Centre Mall in Elliot Lake on June 23, 2012 and Part Two looks at the emergency response to the collapse. Both volumes contain my recommendations for changes to rules, regulations, practices and procedures related to the maintenance and inspection of publicly accessible buildings and the emergency response to disasters. The third volume is an executive summary. I hope that the Report will lead to a safer Ontario. It has been an honour and a privilege to serve as Commissioner. -

Cod Moratorium 20 Years Later (Length: 15:01) 4

Credits Resource Guide Writers: Jill Colyer and Jennifer Watt Host: Michael Serapio Producer: Mike Prokopec Video Writer: Mike Prokopec Production Assistant: Carolyn McCarthy Supervising Manager: Laraine Bone Visit us at our Web site at our Web site at http://newsinreview.cbclearning.ca, where you will find News in Review indexes and an electronic version of this resource guide. As a companion resource, we recommend that students and teachers access CBC News Online, a multimedia current news source that is found on the CBC’s home page at www.cbc.ca/news/. Close-captioning News in Review programs are close-captioned. Subscribers may wish to obtain decoders and “open” these captions for the hearing impaired, for English as a Second Language students, or for situations in which the additional on-screen print component will enhance learning. CBC Learning authorizes the reproduction of material contained in this resource guide for educational purposes. Please identify the source. News in Review is distributed by: CBC Learning, P.O. Box 500, Station A, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5W 1E6 • Tel: (416) 205-6384 • Toll-free: 1-866-999-3072 • Fax: (416) 205-2376 • E-mail: [email protected] • www.cbclearning.ca Copyright © 2012 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News in Review, September 2012 1. Colorado Shooting Rampage (Length: 18:15) 2. Quebec Students Speak Out (Length: 18:11) 3. Cod Moratorium 20 Years Later (Length: 15:01) 4. Elliot Lake Mall Collapse: A Preventable Tragedy? (Length: 16:07) CONTENTS In This Issue ....................................................................................................... -

Ontario Gazette Volume 147 Issue 01, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 147

Vol. 147-01 Toronto ISSN 00302937 Saturday, 4 January 2014 Le samedi 4 janvier 2014 Parliamentary Notice Avis parlementaire Election Finances Act Loi sur le financement des élections Statement by the Chief Electoral Officer Énoncé du directeur général des élections Related to the Indexation Factor au sujet du facteur d’indexation for the Five-Year Period 2014–2018 pour la période de cinq ans allant de 2014 à 2018 Pursuant to subsection 40.1(2) of the Election Finances Act, R.S.O. 1990, Conformément à l’article 40.1, paragraphe 40.1(2) de la Loi sur le Chapter E.7, as amended, notice is hereby given of the statement of the financement des élections, L.R.O. 1990, chap E.7, ainsi modifiée, je indexation factor required by section 40.1, subsection 1, applicable to the vous annonce par les présentes le facteur d’indexation comme l’exige five-year period from January 1st 2014 to December 31st 2018. The indexation l’article 40.1, paragraphe 40.1(1), pour la prochaine période de cinq ans factor was calculated based on the percentage change in the Consumer Price allant du 1er janvier 2014 au 31 décembre 2018. Le facteur d’indexation Index for Canada for prices of all items for the 60-month period ending a été calculé à partir de la variation en pourcentage de l’indice des prix October 31st, 2013 as published by Statistics Canada, rounded to the nearest à la consommation pour le Canada sur les prix de tous les articles pour two decimal points. -

Community Profile

Community Profile CITY OF ELLIOT LAKE, ONTARIO APM-REP-06144-0098 NOVEMBER 2014 This report has been prepared under contract to the NWMO. The report has been reviewed by the NWMO, but the views and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NWMO. All copyright and intellectual property rights belong to the NWMO. For more information, please contact: Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East, Sixth Floor Toronto, Ontario M4T 2S3 Canada Tel 416.934.9814 Toll Free 1.866.249.6966 Email [email protected] www.nwmo.ca . Community Profile: Elliot Lake, ON November 28, 2014 Document History Title: Community Well-Being Assessment – Community Profile – The City of Elliot Lake, ON Revision: 0 Date: June 29, 2012 Hardy Stevenson and Associates Limited Prepared By: Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 1 Date: August 3, 2012 Prepared By: Danya Braun and Dave Hardy Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 2 Date: September 21, 2012 Prepared By: Danya Braun and Dave Hardy Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 3 Date: August 30, 2013 Prepared By: Danya Braun, Andrzej Schreyer, Noah Brotman and Dave Hardy Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 4 Date: January 31, 2014 Prepared By: Danya Braun, Dave Hardy and Noah Brotman Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 5 Date: February 14, 2014 Prepared By: Danya Braun and Dave Hardy Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 6 Date: March 14, 2014 Prepared By: Danya Braun and Dave Hardy Approved By: Dave Hardy Revision: 7 Date: June 4, 2014 Prepared By: Danya Braun and Dave Hardy Approved -

The Retirement Living Years 1999–2005 Leaks from the Rooftop Parking Deck Were an Ongoing Issue in the Mall During the Period of Nordev’S Ownership

SECTION IV The Retirement Living Years 1999–2005 Leaks from the rooftop parking deck were an ongoing issue in the Mall during the period of NorDev’s ownership. In spite of this problem, NorDev spent relatively paltry amounts of money to maintain the roof. CHAPTER New Owner, No New Solutions Background to Retirement Living . 207 The genesis and launch of Retirement Living .................................................. 207 Retirement Living gets off the ground with 1,450 properties and $3.5 million ................. 208 Composition of the membership of Retirement Living ......................................... 208 Retirement Living and the City of Elliot Lake were closely linked ............................... 209 Management of Retirement Living ............................................................ 209 Confidentiality within Retirement Living obstructed the flow of information to the City of Elliot Lake .............................................................................. 210 Retirement Living buys the Algo Centre . .213 Algocen intends to shut the Hotel ............................................................. 213 Algoma is serious about closing the Hotel ..................................................... 214 Retirement Living considers possible ownership of the Mall and the Hotel .................... 214 Algocen maintains control over its information ................................................ 215 Architects provide Retirement Living with a proposal for a building condition assessment .... 217 The City -

Elliot Lake Mall Collapse: a Preventable Tragedy?

News in Review – September 2012 – Teacher Resource Guide Elliot Lake Mall Collapse: A Preventable Tragedy? SETTING THE STAGE Two people were killed and 22 other people were Note to Teachers injured when the roof of the Algo Centre Mall in The classroom must promote a safe place Elliot Lake collapsed on June 23, 2012. The speed for students to discuss sensitive issues such and efficiency of emergency response to the as disaster and death. Prepare students for collapse has been criticized, and the mall's safety the topics that will be discussed and allow and structural integrity will be questioned in a for individual reflective time in addition to public inquiry. small group activities where students can safely process their thoughts and emotions. MINDS ON DISCUSSION 1. Imagine that you just received a text message from your friend saying that a nearby mall/community centre had collapsed. How would you respond? 2. Have you ever been concerned about the structural safety of a building? To whom would you report your concerns? 3. Do you think that the government should be responsible for creating laws regarding the safety of buildings? Why or why not? 4. What problems do you anticipate a rescue crew may have in attempting to find survivors and bodies in a collapsed building? 5. Hypothesize probable causes of the roof collapse of a mall. 6. Locate Elliot Lake on a map of Canada. Determine three distinguishing attributes of this community 28 SEPTEMBER 2012 — ELLIOT LAKE MALL COLLAPSE: A PREVENTABLE TRAGEDY? FOCUS FOR READING As you read the background information below on the Algo Centre Mall collapse, record your answers to the following questions: 1. -

1986–99: Leaks Persist – the Problem Will Be Sold

CHAPTER 1986–99: Leaks Persist – The Problem Will Be Sold 1986–9: The first years of Rod Caughill’s employment by Algocen . 137 Rod Caughill learns of the leaks soon after being hired ........................................ 137 Mr. Caughill is asked to look for solutions ...................................................... 137 1987: Algocen develops a maintenance routine that includes daily checks for loose caulking and water-damaged tiles ............................................................. 138 1988–9: The Library moves to the Mall, despite warnings about leaks .......................... 139 1989: Ken Snow is hired by Algocen as the maintenance supervisor for the Algo Centre and observes visible leaks ..................................................................... 141 1990: The City is hit by mine shutdowns, the leaks persist, and the owner continues to deal with the roof in the same way . .142 The City suffers a significant blow ............................................................. 142 The Mall continues to lose money for Algocen ................................................. 144 Algocen documents its roof maintenance procedures, which never changed .................. 144 1990, A particularly bad year for leaks: Algocen is warned, and agrees, that the roof will “be a problem forever” – and continues to repair it in its usual way ............................ 145 Algoma did not apply for, and the City did not ask for, building permits for any of the repairs .. 148 Algocen gets advice from engineers but does not repair the roof . .148 Autumn 1990: Algocen seeks engineering advice on repairing the leaks and the state of degradation; it had concerns about structural damage from years of leaks .................... 148 January 1991: Trow is retained to provide a condition survey of the parking deck, told that Algocen had concerns about structural damage, and told to report on the structural integrity . -

October 17, 2014 – Vol

October 17, 2014 – Vol. 19 No. 42 New missing persons policy announced Oct 10 2014 TORONTO - The Ontario govern- ment is immediately ending joint road safety blitzes with the Can- ada Border Services Agency be- cause the feds used one to arrest undocumented workers. Page 3 Oct 10 2014 The First Nation community of Opitciwan says it can no longer afford to keep its beleaguered aboriginal police force up and run- ning, despite an agreement signed in March that was designed to help keep the tiny department afloat. Page 3 Oct 15 2014 BANFF, Alta. - Provincial justice ministers are expected to de- Oct 10 2014 of Canada’s approximately 1,181 murdered mand this week that the federal In the wake of its unprecedented and missing aboriginal women. government recommit to funding report on murdered and missing In an interview with The Globe and the legal aid program. aboriginal women, the RCMP has Mail shortly before the policy was finalized, Page 5 rolled out a revamped national RCMP Superintendent Tyler Bates said missing persons policy, including the forms would reinforce the “gravity” of Oct 16 2014 a pair of investigative tools that missing-person cases and ensure every in- provide a lens into how police ap- OTTAWA - The federal govern- vestigative angle is explored. proach disappearances. The detailed missing-person intake re- ment plans to amend the law gov- The policy, which was circulated to port could prove burdensome for officers erning the Canadian Security In- commanding officers in September, in- who are already “stretched to the limit,” said telligence Service to give the spy troduces two standardized documents: a Inspector Mario Giardini, who heads the agency more authority to track 13-question risk-assessment form and a 10- Vancouver Police Department’s diversity terrorists overseas. -

2014 Annual Report

Strategic Clarity Annual Review 2014 Contents PEO STAFF CONTACTS CONTENTS Association staff can provide information about PEO. 2 Council list/staff contacts/contents For general inquiries, simply phone us at 416-224-1100 3 President’s message or 800-339-3716. Or, direct dial 416-840-EXT using 4 Registrar’s report/Register the extensions below. 5 2014 Statistics at a glance 6-9 Strategic clarity REGULATORY PROCESS EXT 10-11 Abbreviated financials (full financial statements available on PEO’s Registrar website and in the May/June issue of Engineering Dimensions) Gerard McDonald, P.Eng., MBA 1102 12-13 Chapter highlights Senior executive assistant 14 Honours Becky St. Jean 1104 16-19 Volunteers Deputy registrar, regulatory compliance Linda Latham, P.Eng. 1076 Manager, complaints and investigations 2014-2015 PEO COUNCIL AND EXECUTIVE STAFF Ken Slack, P.Eng. 1118 Officers Manager, enforcement President West Central Region councillors Marisa Sterling, P.Eng. 647-259-2260 J. David Adams, P.Eng., MBA, FEC Robert Willson, P.Eng. Deputy registrar, licensing and finance Past president Danny Chui, P.Eng., FEC Michael Price, P.Eng., MBA, FEC 1060 Annette Bergeron, P.Eng., MBA, FEC Lieutenant governor-in-council appointees Manager, admissions President-elect Ishwar Bhatia, MEng, P.Eng., FEC Moody Farag, P.Eng. 1055 Thomas Chong, MSc, P.Eng., FEC, PMP Santosh K. Gupta, PhD, MEng, Manager, licensure Vice president (elected) P.Eng., FEC Pauline Lebel, P.Eng. 1049 George Comrie, MEng, P.Eng., CMC, FEC Richard J. Hilton, P.Eng. Manager, registration Vice president (appointed) Rebecca Huang, LLB, MBA Lawrence Fogwill, P.Eng. 1056 Michael Wesa, P.Eng., FEC Vassilios Kossta Supervisor, examinations Executive members Mary Long-Irwin Anna Carinci Lio 1095 Nicholas Colucci, P.Eng., MBA, FEC Sharon Reid, C.Tech. -

(12-19) June 27, 2012 Page 1 of 9 The

THE CORPORATION OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF HURON SHORES (12-19) June 27, 2012 The regular meeting of the Council of the Corporation of the Municipality of Huron Shores was held on Wednesday, June 27, 2012, and called to order by Mayor Gil Reeves at 7:00 p.m. PRESENT WERE: Mayor Gil Reeves, Councillors Georges Bilodeau, Gord Campbell, Eloise Eldner, Ted Linley, Kent Weber and Dale Wedgwood. REGRETS: Councillors Jane Armstrong and Debora Kirby. ALSO PRESENT: Bill Richardson; Kerri-Lee Cinq-Mars; Tim Armstrong; Clerk/Administrator Deborah Tonelli; Administrative Assistant Carla Slomke AGENDA REVIEW Clerk/Administrator advised of the items added under Addenda #1 and #2 as well as the deferment of items 8-3 to 8-11 with regard to the Weight Limit Restrictions on various bridges in the Municipality. Deferral of Item 8- 14 was also noted later in the meeting. DECLARATION OF PECUNIARY INTEREST Clerk/Administrator reported that Councillor Armstrong had advised staff of a pecuniary interest with regard to the Armstrong Enterprises account. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 12-19-01 BE IT RESOLVED THAT Council adopts the minutes of the D. Wedgwood Regular Meeting of Council held Wednesday, June 13th, E.W. Linley 2012, as circulated. CARRIED. ADOPTION OF ACCOUNTS 12-19-02 BE IT RESOLVED THAT Council approves payment of the D. Wedgwood General Accounts, excluding items of Pecuniary Interest, E. Eldner for the period from June 14th to June 27th, 2012, in the amount of $87,044.13. CARRIED. 12-19-03 BE IT RESOLVED THAT Council approves payment of the D. Wedgwood Armstrong Enterprises account in the amount of E.