University of Birmingham Learning Through Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of the Archives of the WAR RESISTERS' INTERNATIONAL (WRI) 1921-1991 J.R

List of the archives of the WAR RESISTERS' INTERNATIONAL (WRI) 1921-1991 J.R. van der Leeuw INTRODUCTION The War Resisters' International (WRI) was founded in 1921 by Kees Boeke and others under the name `Paco' (Peace in Esperanto) at Bilthoven, The Netherlands, at a small conference of representatives of some European radical peace organizations. Two years later the secretariat moved to Enfield, a suburb of London. On this occasion the organization changed its name into War Resisters' International. It went to London in 1968, where it stayed until 1974, then it was located at Brussels. The secretariat returned to London in 1980. The WRI is the oldest and most stable undenominational international federation of national and some regional and local radical pacifist organizations in the world. Originally the assistance to Conscientious Objectors (CO's) and the struggle for the recognition of conscientious objection as a human right stood on the foreground. Later the non-violent action against (nuclear) war, war preparation, militarism, arms industry and arms trade and all causes of war became major points. The WRI cooperated with a number of congenial international organizations, such as the anarchist International Anti-Militarist Bureau and the christian International Fellowship of Reconciliation. It was a participant in some organized concerted actions, like the Joint Peace Council and the Rassemblement Internationale contre la Guerre et le Militarisme. WRI introduced the Broken Rifle as its symbol in 1932. WRI published the annual Roll of Honour (of war resisters in prison) and celebrated the yearly Prisoners of Peace Day (1st December). Its strongest affiliated groups (`sections') were in Western Europe and the United States of America. -

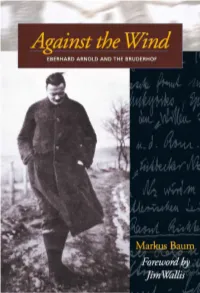

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33 -

Page 1 Origins: VI 10 November 2016

Origins: VI 10 November 2016 Page 1 Table of Contents A Framework for Big History The Montessori primary school and Cosmic Education as ‘prepared environment’ for Anne-Marie Poorthuis ........... 4 Cosmic Education Marg Paulussen, Wim van Schie, Ingrid Bes .......... 32 Montessori, a cosmic approach of education Characteristics of Cosmic Jos Werkhoven .......... 11 Educators and Teachers Rietje van Stek-Lander .......... 35 Mike and the fossil, an example of how to get children Once upon a time …… involved in Big History there was a story to be told…… Bea Heres Diddens .......... 18 Jos Werkhoven .......... 36 Cosmic Education and Cosmic Education in the First Dutch Big History to foster and Montessori School in The Hague development of children from 0-6 Nicoline van Ginkel ........ 45 years Vita Verwaayen, Tatiana de Riedmatten .......... 23 Origins Editor: Lowell Gustafson, Villanova University, Pennsylvania (USA) Origins. ISSN 2377-7729 Thank you for your Associate Editor: Cynthia Brown, Dominican University of California (USA) membership in Assistant Editor: Esther Quaedackers, University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) Please submit articles and other material to Origins, Editor, [email protected] the IBHA. Your membership dues Editorial Board Mojgan Behmand, Dominican University of California, San Rafael (USA) The views and opinions expressed in Origins are not necessarily those of the IBHA Board. all go towards the Craig Benjamin, Grand Valley State University, Michigan (USA) Origins reserves the right to accept, reject or edit any material submitted for publication. adminsitration of David Christian, Macquarie University, Sydney (Australia) the association, but do not by Andrey Korotayev, Moscow State University (Russia) International Big History Association themselves cover Johnathan Markley, University of California, Fullerton (USA) Brooks College of Interdisciplinary Studies our costs. -

Het Leven En De Werkplaats Van Kees Boeke (1884-1966)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) De geest in dit huis is liefderijk: het leven en De Werkplaats van Kees Boeke (1884-1966) Hooghiemstra, D.A. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hooghiemstra, D. A. (2013). De geest in dit huis is liefderijk: het leven en De Werkplaats van Kees Boeke (1884-1966). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 4. De eerste tien jaar van De Werkplaats Een ‘paedagogisch experiment’ Kees had altijd al gedacht dat zijn werk ‘uiteindelijk op opvoeding en onderwijs zou uitloopen’. Toch ontstond De Werkplaats volgens hem ‘feitelijk toevallig’.1 De nieuwe regel dat schoolgeld voortaan via de be- lasting geïnd werd, had hem in het najaar van 1926 gedwongen om zijn kinderen van school te halen. -

Download De Vriendenkring Van April 2021

Maandblad van de Nederlandse Quakers, het Religieus Genootschap der Vrienden . 92e jaargang nr. 4, april 2021 Bescherm onze gemeenschappen, beweging gesteund door AFSC, Amerikaanse Hulporganisatie van de Quakers 1 De Vriendenkring ISSN: 0167 – 3807 Maandblad van het Religieus Genootschap der Vrienden (Quakers) Abonnementsprijs: Nederl.: €30,00 per jaar Europa en Wereldwijd €75,00 per jaar Email abonnement (PDF) €5,00 per jaar Deze Vriendenkring is gedrukt op milieuvriendelijk Het gebeurt helaas weleens dat abonnees ver- papier met deze drie certificaten geten te betalen. Maak daarom van de betaling van het abonnement een periodieke overmaking. Bankrekening: (IBAN) NL65 TRIO 0212 3772 64 t.n.v. Quakers te Drieber- gen met vermelding van 'Abonnement De Vriendenkring'. Voor buitenland: (BIC) TRIONL2U Nieuwe abonnees, adreswijzigingen en betalingen: [email protected] Redactieleden: Eindredactie: Sytse Tjallingii, Van Nispensingel 5, 8016 LM, Zwolle, tel. 038-4608461/06-40030923. Email: [email protected], Schrijver: Hylkia Nieuwerth Redactielid: Els Ramaker Correctie: Hylkia, Els en Frieda Oudakker. Voor abonnees met gezichts- of leesproblemen was er een gesproken versie van De Vriendenkring. Als je hier behoefte aan hebt neem dan contact op met de redactie. Kopij voor De Vriendenkring is heel erg welkom voor de 15e van iedere maand! (Tenzij anders afgesproken). De Vriendenkring staat in kleur op de website, waar je nog een schat aan aanvullende en actuele informatie over de Qua- kers vindt. Bezoek daarom geregeld de Quaker website: www.Quakers.nu De Nederlandse Quakers hebben, naast de website quakers.nu (waarop de Vrienden- kring te vinden is), een Facebookpagina “Quakers Nederlandse Jaarvergadering” voor berichten en een besloten Facebookgroep “Nederlandse Jaarvergadering” voor onderling gesprek, ook met Vriendenkringabonnees. -

100 Jahre Für Gewaltfreiheit 1

100 Jahre für Gewaltfreiheit 1 iforInternational Fellowship of Konstanz 1 91 4 -201 4 -201 4 91 Konstanz 1 Reconciliation 100 Jahre für Gewaltfreiheit Gemeinsam für Gewaltfreiheit und Versöhnung ensemble pour la nonviolence et la réconciliation ifor-mir.ch Gemeinsam für Gewaltfreiheit und Versöhnung 100 Jahre für Gewaltfreiheit 3 Vorwort Über Generationen hinweg haben Mitglieder des Ver- • absoluten Respekt vor dem Menschen söhnungsbundes in aller Welt, beseelt von der Hoff- • Glauben an die Kraft der Liebe und Versöhnung nung, dass Abrüstung und Frieden einmal Realität • Suche nach Wahrheit werden könnten, unermüdlich an der Friedensaufgabe • Gewaltfreiheit festgehalten. Das verdient nicht nur Hochachtung, • Bemühung um Frieden und soziale Gerechtigkeit sondern ist zugleich Verpflichtung, auch weiterhin in der Welt ebenso unerschrocken und unbeirrbar Zeugen für die Hoffnung wider alle Hoffnungslosigkeit zu sein! Gemeinsam bekämpfen wir Unrecht und Gewalt- tätigkeit, Krieg und dessen Vorbereitung und tragen Als weltweites Netzwerk von spirituell verwur- damit unseren Teil zu einer friedlicheren und gerech- zelten Friedensgruppen verbindet IFOR heute Men- teren Welt bei. schen verschiedener Nationen, Kulturen, Religionen und Weltanschauungen und eint sie im Grundsatz, Zu seinem 100-Jahr-Bestehen gratuliere ich als dass Konflikte nicht mit Krieg und Gewalt gelöst wer- Co-Präsident des Schweizerischen Zweiges der IFOR- den sollten und dürften. Bewegung ganz herzlich und wünsche den IFOR- Mitgliedern in aller Welt für die Zukunft alles Gute. Als parteilich und religiös unabhängige und ge- Auch lade ich Sie ein, gemeinsam mit uns den Weg meinnützige Organisation steht IFOR seit über 100 der Gewaltfreiheit zu gehen, damit unser Traum einer Jahren für: gewaltfreien Zukunft einmal Wirklichkeit wird. -

Spiritual Leaders in the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1

A Lexicon of Spiritual Leaders In the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1 Version 3 Page 1 of 52 2010 Dave D’Albert Argentina ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Adolfo Pérez Esquivel 1931- .......................................................................................................... 3 Australia/New Zealand ........................................................................................................................ 4 E. P. Blamires 1878-1967 ............................................................................................................... 4 Austria ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kaspar Mayr 1891-1963 .................................................................................................................. 5 Hildegard Goss-Mayr 1930- ............................................................................................................ 6 Belgium ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Jean van Lierde ............................................................................................................................... 8 Czech ................................................................................................................................................. -

Kurze Geschichte Der SOZIOKRATIE

Kurze Geschichte der SOZIOKRATIE Der Begriff „Soziokratie“ wurde zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts vom französischen Philosophen und Soziologen August Comte geprägt und später vom US- amerikanischen Soziologen Lester Frank Ward erwähnt. Jedoch blieb die Soziokratie eine Theorie, bis der international bekannte Friedensaktivist und Pädagoge Kees Boeke ab 1926 das erste funktionierende soziokratische System entwickelte und in seinem Internat, Werkplaats Kindergemeenschap, als Organisationsform einführte. Der spätere Ingenieur, Gerard Endenburg, geb. 1933 in Holland, hat die Jahre von 1939 – 1945 in dieser, von Kees Boeke und Betty Cadbury gegründeten ersten, soziokratischen Schule verbracht. Basierend auf den Prinzipien Boekes entwickelte Gerard Endenburg für das von seinem Vater übernommene Unternehmen ab 1968 eine Steuerungsmethode (Führungsstruktur), die sog. Soziokratische Kreisorgani- sationsMethode SKM. Diese war weitreichend verwendbar. Ausgehend vom Sociocratisch Centrum Nederland, das Gerard Endenburg 1976 gründete, kam die Soziokratie in den 1980er-Jahren in die USA, nach Südamerika und Canada. Heute gibt es weltweit unzählige Organisationen, Zentren und Berater-Gruppen, die Soziokratie verbreiten. Sehr bekannt ist die Soziokratie nach Gerard Endenburg in Canada, Brasilien, Frankreich, USA, Indien, Australien, Spanien und Österreich. Ausgehend vom Soziokratie Zentrum Österreich, hielt die Methode ab 2013 auch Einzug in die Schweiz, Deutschland und zuletzt in Griechenland. Auch Abwandlungen der ursprünglich von Gerard Endenburg entwickelten SKM – Soziokratische KreisorganisationsMethode wurden entwickelt, wie zB.: Holacracy (Brian Robertson, ab 2006), Sociocracy 3.0 (James Priest, ab 2014), Das kollegial geführte Unternehmen (Bernd Östereich, ab 2016). Um einen Einblick in die Geschichte der Soziokratie am Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts zu geben, drucken wir hier die englische Kurzfassung eines Pamphlets, dessentwegen Kees Boeke kurz vor dem 2. -

University of Birmingham Learning Through Culture

University of Birmingham Learning through culture Grosvenor, Ian; Pataki, G DOI: 10.1080/00309230.2016.1264981 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Grosvenor, I & Pataki, G 2017, 'Learning through culture: seeking “critical case studies of possibilities” in the history of education', Paedagogica Historica, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 246-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2016.1264981 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Paedagogica Historica on 10th February 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/00309230.2016.1264981 Checked 23/2/2017 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

A History of Consensus

Rhizome guide to A History of Consensus Consensus decision-making has been used in its current form since the 1960s and 70s, which are often credited as the birthplace of consensus. However there were many forms of participatory decision-making in use long before then - historical groups, peoples and communities who have had an egalitarian ethos and approach to decision-making. These are not consensus as we discuss it in our Guide to Consensus Decision- Making, but they have recognisable connections and shared qualities which have fed into and inspired consensus decision-making. Contemporary consensus in action: a ‘general assembly’ at Occupy Wall Street (CC) Caroline Schiff Indigenous consensus The spirit of consensus Examples of indigenous cultures cited as using There are also a number of religious denominations consensus-like processes include the Aymara of the with a more radical interpretaion of their faith that Bolivian Altiplano, the San bushmen of the Saharan have chosen to use consensus-like decision-making. region, and the Haudenosaunee first nations people Quakers and Ahabaptists are notable in this regard, of modern day USA. Whilst these cultures were all but not alone. These groups tended to use (and still hierarchical, at least in the sense that some use in the case of Quakers and Anabaptists) a leadership roles were allocated to specific unanimous model of decision-making. individuals, there was (is, in some cases) a real sense Researcher Ethan Mitchell writes: that the will of the community prevailed through “The consensus process used by the Society of Friends discussion and debate. Any leaders were seen only (Quakers) has been in use for three and a half as first amongst equals. -

Juli 2019 Werkplaatsbo Wpkeesboeke.Nl @ Mislukken.” Basisonderwijs Hutten Bouwen in De Bosrand Wat Leren Ze Nou in De Zandbak?

“Het doel der opvoeding is: elk kind te helpen worden wat het is”. Kees Boeke Basisonderwijs “Iets kan Kees Boekelaan 10 3723 BA Bilthoven Directeur: Anne-Mieke Bulters alleen lukken krant T 030 228 28 42 als het mag jaargang 35 | nummer 36 | juli 2019 werkplaatsbo wpkeesboeke.nl @ mislukken.” www.wpkeesboeke.nl Basisonderwijs Hutten bouwen in de bosrand Wat leren ze nou in de zandbak? Algemeen Zestig jaar Tiendesprong Voortgezet onderwijs Werk dan mee in De Werkplaats Voortgezet onderwijs Kees Boekelaan 12 3723 BA Bilthoven Ludodidactiek Rector: Jeroen Croes Miljeugd T 030 228 28 41 werkplaatsvo wpkeesboeke.nl @ www.wpkeesboeke.nl bo Redactioneel zomer 2019 Hutten bouwen in de bosrand ‘Samen leren door creëren’, ‘hoofd, hart Kees Boeke zelf komt trouwens ook Een onderdeel van de creatieve ontwik- keken elkaar aan en weer anderen gingen als werkers in de pauze: we wilden niet en handen’: credo’s van Kees Boeke die weer even langs. Oud-medewerkers Jos keling van het team geheimzinnig doen. stoppen en bewaakten onze hut met onze we allemaal kennen, maar in hoeverre Heuer en Henk Willems werken samen De BO-medewerkers kwamen op de levens. passen we ze toe in ons onderwijs? Hoog aan een boek over de Tiendesprong studieochtend van 16 mei nieuwsgierig Ik keek naar degene naast me; we hadden tijd om een themanummer te wijden aan en eerstgenoemde maakte voor de binnen. Op de agenda stond: Wat is een contact en grepen een goudkleurige plas- Samenhang en visie blijven ontwikkelen en alles wat daarmee WP-Krant een prachtig overzicht van creatief proces? Tessa Hendriks, boom- tic buis, net voordat een ander die gepakt Over deze aanpak was nagedacht, het samenhangt. -

Resources to Sustain the Military Campaign

1 MEMORIC MEMORY BEYOND RHETORIC IMPRINT Authors: Valerie Weidinger, Katerina Stoyanova, Nevena Sicevic, Marta Palau Albà, Michael Rösser Proofreading: Ela Suleymangil Photos: Marta Palau Albà, Zuzana Buodová, Nevena Sicevic, and the international archives of SCI. Special thanks to: Sara Turra, and all activists in SCI movement who offered inspiration and ideas for this e-booklet Design: Balázs Kajor | Memoric logo: Marta Palau Albà All content licensed under Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported” (CC BY-SA 3.0) unless stated otherwise – quotes remain the property of the respective copyright holders. For the licence agreement, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/legalcode, and a summary (not a substitute) at http://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-sa/3.0/deed.en This publication forms part of the project “Memory beyond Rhetoric: World War I and the growth of the pacifist movement in Europe”, short “Memoric”, implemented by Ser- vice Civil International (SCI) and co-funded by the Europe for Citizens Program of the European Union. The e-booklet was written and revised by the coordination team and the volunteers of Memoric. It does therefore not automatically represent the opinion of SCI or the European Union. All sources of information are mentioned in the list of links at the end of the publication. CONTENT INTRODUCTION 7 The WAR to end ALL Wars 11 DIFFerent seeds – GroWth OF the paciFist moVement 19 Memoric VOLunteers’ Voices 31 NON-FormaL education: memoric WORKshops 37 Don’t Be Puzzled with Europe! The Power of Propaganda Building Peace in Modern Society Memoric Quiz Human Rights during the First World War Commemoration through Memorials HOW to become actiVE For peace 65 Peace on a personal level 3,2,1… Act for Peace! LinKS & Videos 68 Photo: 1924, Someo, Switzerland Introduction World War I changed the course of history forever, and marked the start of the 20th century in many ways.