Formula for Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deepening EU-Georgian Relations

Deepening EU–Georgian Relations Deepening EU–Georgian Relations What, why and how? Second edition Edited by Michael Emerson and Tamara Kovziridze CEPS contributors Reformatics Steven Blockmans contributors Michael Emerson Giorgi Akhalaia Hrant Kostanyan David Bolkvadze Guillaume Van Der Loo Zaza Chelidze Giorgi Chitadze Gvantsa Duduchava Lali Gogoberidze Alexandre Kacharava Helen Khoshtaria Tamara Kovziridze Vakhtang (Vato) Lejava Natia Samushia George Zedginidze One of a trilogy of Handbooks explaining the EU’s Association Agreements and DCFTAs with Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels Reformatics, Tbilisi Rowman & Littlefield International, London Published by Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB www.rowmaninternational.com Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd is an affiliate of Rowman & Littlefield 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706, USA With additional offices in Boulder, New York, Toronto (Canada), and Plymouth (UK) www.rowman.com Copyright © 2018 CEPS CEPS Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ceps.eu Illustrations by Constantin Sunnerberg ([email protected]) The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-78660-800-0 Paperback 978-1-78660-799-7 Hardback 978-1-78660-801-7 Ebook The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Country of Origin Information Report Republic of Georgia 25 November

REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT Country of Origin Information Service 25 November 2010 GEORGIA 25 NOVEMBER 2010 Contents Preface Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.05 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Post-communist Georgia, 1990-2003.................................................................. 3.02 Political developments, 2003-2007...................................................................... 3.03 Elections of 2008 .................................................................................................. 3.05 Presidential election, January 2008 ................................................................... 3.05 Parliamentary election, May 2008 ...................................................................... 3.06 Armed conflict with Russia, August 2008 .......................................................... 3.09 Developments following the 2008 armed conflict.............................................. 3.10 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................................... -

Natural Resource Management and Factors Conducive to Elite Corruption

Association Green Alternative is a non-governmental, non-profit organization founded in 2000. The mission of Green Alternative is to protect the environment, biological and cultural heritage of Georgia through promoting economically sound and socially acceptable alternatives, establishing the principles of environmental and social justice and upholding public access to information and decision-making processes. We organize our work around six thematic and five cross- cutting areas. Thematic priority areas include: energy – extractive industry – climate change; transport sector and environment; privatization and environment; biodiversity conservation; waste management; water management. Cross-cutting priority areas include: environmental gover- nance; public access to information, decision-making and justice; instruments for environmental management and sustainable development; European Neighbourhood Policy, monitoring of the lending of the international finan- Natural Resource Management and cial institutions and international financial flow in Georgia. Factors Conducive to Elite Corruption Green Alternative cooperates with non-governmental organizations both inside and outside Georgia. In 2001 Green Alternative, along with other local and international non-governmental organizations, founded a network of observers devoted to monitoring of development of a poverty reduction strategy in Georgia. Since 2002 Green Alternative has been monitoring implementation of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline project, its compliance with the policies and guidelines of the international finan- cial institutions, the project’s impacts on the local popula- tion and the environment. Since 2005 the organization has been a member of the Monitoring Coalition of the ENP (European Neighbourhood Policy) Action Plan. In 2006 Green Alternative founded an independent forest monitor- ing network. Since establishment Green Alternative is a member of CEE Bankwatch Network – one of the stron- gest networks of environmental NGOs in Central and East- ern Europe. -

THE GEORGIAN TAXATION SYSTEM – an OVERVIEW Tbilisi, May 2010

THE GEORGIAN TAXATION SYSTEM – AN OVERVIEW Tbilisi, May 2010 Executive Summary Taxation – fundamental to state formation and the provision of state services – has long been an issue that has plagued Georgia. Before the Rose Revolution, there was widespread tax avoidance and evasion, reflecting state weakness and corruption, and impacting severely on service delivery. With political will, and specifically with the introduction of a new tax code in 2005, there has, however, been a major change in the Georgian fiscal landscape. Taxes have been slashed, procedures streamlined, corruption eliminated and compliance greatly improved. Reflecting this has been a massive increase in the government’s tax-take. There are, however, some major caveats. The tax administration, while improved, is still less than efficient, and crucially has failed to apply risk analysis or other auditing mechanisms in selecting businesses for tax audits. As well as a waste of administrative resources, this fundamental omission has also allowed for the re-emergence of some disturbing practices. The excesses of the Financial Police, all too evident in the first few years of the Saakashvili administration, are again a fact of life for many businesses in Georgia. Budgetary shortfalls are a major motivating factor, but so too are political considerations, with tax audits, as one commentator noted, being used as a political club. While the authorities have recognised that low taxes contribute to economic growth, they have failed to apply fiscal instruments to various policy areas. Reflecting an extreme liberal economic outlook, taxation has not been used as a lever to promote job creation in specific sectors or regions. -

National Competitiveness Report Georgia 2012/2013 Toward a Multi-Sector Regional Hub

NATIONAL COMPETITIVENESS REPORT GEORGIA 2012/2013 TOWARD A MULTI-SECTOR REGIONAL HUB National Competitiveness Report Georgia 2012/2013 TOWARD A MULTI-SECTOR REGIONAL HUB Tbilisi, Georgia 2013 ISET Policy Institute is one of the first university-based think-tanks in the South Caucasus. It is based at the International School of Economics (ISET) of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University (TSU) in Georgia. Established in May 2011, ISET-PI builds upon ISET’s academic strength and TSU’s tradition of excellence and social engagement. Authors: Eric Livny, Andrei Sarychev, Giorgi Bakradze, Irakli Galdava, Giorgi Kelbakiani, Givi Melkadze, Giorgi Mekerishvili Design by Giorgi Balakhashvili Acknowledgements This report was prepared in cooperation with the Economic Prosperity Initiative by USAID as part of a concentrated effort to promote Georgia’s global competitiveness. Special thanks go to Barrie Hebb, Kevin Murphy and Alan Saffery for providing methodological guidance and training early on in the process, to Tina Mendelson for expert opinion and advice, and to Tamuna Kapianidze for helping organize public discussion and promote the competitiveness agenda. Major segments in this report follow the World Economic Forum’s methodology, and we are indebted to WEF for sharing their data and knowledge. Invaluable assistance in the process of data collection was provided by Irina Kvachadze from the Business Association of Georgia, who helped organize more than 30 interviews with the CEOs of the largest Georgian companies. Naturally, we would like to thank all those who agreed to interview for the report and connecting it to the reality on the ground, including current and former Ministers Davit Narmania, Giorgi Kvirikashvili, David Kirvalidze, and Dimitri Gvindadze. -

![Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0690/georgia-republic-recent-developments-and-u-s-1850690.webp)

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs May 18, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-727 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary The small Black Sea-bordering country of Georgia gained its independence at the end of 1991 with the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The United States had an early interest in its fate, since the well-known former Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, soon became its leader. Democratic and economic reforms faltered during his rule, however. New prospects for the country emerged after Shevardnadze was ousted in 2003 and the U.S.-educated Mikheil Saakashvili was elected president. Then-U.S. President George W. Bush visited Georgia in 2005, and praised the democratic and economic aims of the Saakashvili government while calling on it to deepen reforms. The August 2008 Russia-Georgia conflict caused much damage to Georgia’s economy and military, as well as contributing to hundreds of casualties and tens of thousands of displaced persons in Georgia. The United States quickly pledged $1 billion in humanitarian and recovery assistance for Georgia. In early 2009, the United States and Georgia signed a Strategic Partnership Charter, which pledged U.S. support for democratization, economic development, and security reforms in Georgia. The Obama Administration has pledged continued U.S. support to uphold Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The United States has been Georgia’s largest bilateral aid donor, budgeting cumulative aid of $2.7 billion in FY1992-FY2008 (all agencies and programs). -

Businessmen in Politics and Politicians in Business

Businessmen in Politics and Politicians in Business Problem of Revolving Door in Georgia Transparency International Georgia Tbilisi 2013 The report was prepared with financial support from the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida)The content and opinions expressed in the report are those of Transparency International Georgia and do not reflect the position of Sida. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 5 II. What is Revolving Door? ........................................................................................................................... 8 III. Revolving Door in Georgia: Regulations and Practice ............................................................................ 10 Parliament ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Executive Branch ..................................................................................................................................... 18 Local Government ................................................................................................................................... 23 Independent Regulators ......................................................................................................................... -

DEEPENING EU-GEORGIAN RELATIONS Made by Georgia and the Challenges Posed by Their Implementation

EMERSON & KOVZIRIDZE & EMERSON The signing of the Association Agreement and DCFTA between Georgia and the European Union in 2014 was a strategic political act to deepen the realisation of Georgia’s ‘European choice’. Of all the EU’s eastern neighbours, Georgia has distinguished itself by pushing ahead in the years since the Rose Revolution of 2003 with the most radical economic liberalisation and reform agenda. It has notably DEEPENING succeeded in reducing corruption and establishing a highly favourable business climate. The Association Agreement and DCFTA thus build on a most promising base. The purpose of this Handbook is to make the legal content of the Association EU-GEORGIAN RELATIONS Agreement clearly comprehensible. It covers all the significant political and economic chapters of the Agreement, and in each case explains the meaning of the commitments DEEPENING EU-GEORGIAN RELATIONS RELATIONS EU-GEORGIAN DEEPENING made by Georgia and the challenges posed by their implementation. What, why and how? A unique reference source for this historic act, this Handbook is intended for professional readers, namely officials, parliamentarians, diplomats, business leaders, lawyers, consultants, think tanks, civil society organisations, university teachers, trainers, students and journalists. The work has been carried out by two teams of researchers from leading independent think tanks, CEPS in Brussels and the Reformatics policy consulting firm in Tbilisi, with the support of the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida). It is one of -

Full Report 4245.Pdf

DIGEST # 5 MAY/JUNE 2012 YEAR Societies (IFRC), Georgian that lead to the improvement of hard Delegation, as well as the Assistant/ living condition of thousands of IDP Senior Programmer of Public families who previously had been Affairs Section, the US Embassy in abandoned without attention for Georgia. She undertook MA Course years. in International Education Policy There are still lots of families who at Columbia University, NYC, USA are waiting for accommodation and various US State Department process and improvement of their professional development courses. living conditions, and I know that the Before being appointed on the new Prime Minister together with current position of the Minister new Government will implement of Internally Displaced Persons already launched processes more from the Occupied Territories, rapidly. NEW MINISTER OF Accommodation and Refugees of I would like to wish successes to INTERNALLY DISPLACED Georgia she was the member of the new Minister in her complex and PERSONS FROM THE Government and the Minister of responsible position. OCCUPIED TERRITORIES, Education and Culture of A/R of Thanks to all of my colleagues and Abkhazia, Georgia. staff members, as well as to donors ACCOMMODATION AND and partner organizations, IDPs REFUGEES OF GEORGIA FORMER MINISTER and everyone who supported our KOBA SUBELIANI activities. DALI KHOMERIKI On 4 July 2012, the Prime Minister STATISTICS of Georgia, Ivane Merabishvili, introduced Ms. Dali Khomeriki as a IN RESULT OF RUSSIAN new Minister of Internally Displaced OCCUPATION, -

To Download the Pdf-Version, Please Click Here

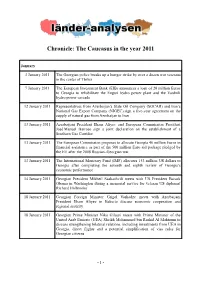

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2011 January 3 January 2011 The Georgian police breaks up a hunger strike by over a dozen war veterans in the center of Tbilisi 7 January 2011 The European Investment Bank (EIB) announces a loan of 20 million Euros to Georgia to rehabilitate the Enguri hydro power plant and the Vardnili hydro power cascade 12 January 2011 Representatives from Azerbaijan’s State Oil Company (SOCAR) and Iran’s National Gas Export Company (NIGEC) sign a five-year agreement on the supply of natural gas from Azerbaijan to Iran 13 January 2011 Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and European Commission President José Manuel Barroso sign a joint declaration on the establishment of a Southern Gas Corridor 13 January 2011 The European Commission proposes to allocate Georgia 46 million Euros in financial assistance as part of the 500 million Euro aid package pledged by the EU after the 2008 Russian–Georgian war. 13 January 2011 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) allocates 153 million US dollars to Georgia after completing the seventh and eighth review of Georgia’s economic performance 14 January 2011 Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili meets with US President Barack Obama in Washington during a memorial service for veteran US diplomat Richard Holbrooke 18 January 2011 Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze meets with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in Baku to discuss economic cooperation and regional security 18 January 2011 Georgian Prime Minister Nika Gilauri meets with Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirate (UEA) -

Nika Gilauri, Reformatics

NIKA GILAURI, REFORMATICS Nika Gilauri was born in Tbilisi in 1975. He studied International Economic Relations at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, graduated in Economics and Finance from University of Limerick in Ireland, and obtained MBA degree in International Business Management at Temple University in Philadelphia. He started his professional career as a finance and management consultant in Georgia, first in Telecom and later in the state energy industry (at the time of Georgian revolution in 2003, bringing down President Eduard Shevardnadze after more than 20 years of rule). He was succeeded by Mikheil Saakashvili, initiating extensive reforms in the country, experiencing low economic development and extremely high corruption level (127th out of 132 in Transparency International’s Index). Gilauri joined the Government of Georgia in December 2003 as Deputy Prime Minister, aged only 28. The experiences he gained in the energy sector recommended him for the position of the Minister of Energy, which he took in February 2004 with the aim to resolve the problem of instability and corruption in the energy sector. He immediately dismissed more than 3,000 executives in this sector and appointed managers for the most important positions, explaining metaphorically that “doctors make the worst hospital directors”. In only a couple of years, the reforms turned Georgia from a country with daily extended restrictions to an electricity exporter. The success in countering corruption further recommended him for the Minister of Finance. He took up the position in 2007 and tackling corruption in the customs was his primary task. He led one of the most extensive tax reforms in Europe, with Georgia reducing the number of taxes from 21 to nine, and further minimizing it to only five by the time the reform was finalized (abolished road taxes, social tax, absolute rights transfer tax...). -

Amendments Made in Tax and Customs Code December 2008 1 Ministry of Finance of Georgia Tax Reduction Timeline

Amendments Made in Tax & Customs Code Ministry of finance of Georgia December 2008 Ministry of Finance of Georgia Reform of the Georgian tax and customs system • Over the recent years, radical changes have been made to tax and customs legislation in Georgia • A new Tax Code came into force on 1 January 2005 and a new Customs Code on 1 January 2007 with the following objectives . Facilitating economic growth – with a minimum number of taxes and low tax rates . Establishing a stable and attractive investment environment – by setting up a solid legal framework and introducing liberal economic principles . Supporting legal business – by using strengthened and flexible administration mechanisms to identify and deter dishonest taxpayers . Ensuring an increased culture of taxpaying – through simplified administrative mechanisms and improved taxpayer support Amendments Made in Tax and Customs Code December 2008 1 Ministry of Finance of Georgia Tax reduction timeline ‘04A ‘05A ‘06A ‘07A ‘08F ‘09F ‘10F ‘11F ‘12F ‘13F Number of 21 7 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 6 Taxes VAT 20% 20% 18% 18% 18% 18% 18% 18% 18% 18% Social Tax + Social Tax + 12- 12% 12% 12% Income Tax Income Tax Income Tax 20% 18% 15% 15% 20% flat flat flat 32% 25% 20% Social Tax 33% 20% 20% 20% - - - - - - Corporate 20% 20% 20% 20% 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% Profit Tax Dividend 10% 10% 10% 10% 10% 5% 5% 3% 0% 0% income tax . Out of 21 taxes under the former tax code, only 6 exist today . Tax rates reduction timetable has been further accelerated in key tax rates in 2008 .