A COMPARATIVE STUDY of F3 HI HALOPERIDOL and [ 3 HI SPIROPERIDOL BINDING to RECEPTORS on RAT CEREBRAL MEMBRANES 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacology and Toxicology of Metiamide, a Histamine H

9 November 1974 S.-A. MEDIESE TYDSKRIF 2253 Pharmacology and Toxicology of Metiamide, a - Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonist R. W. BRIMBLECOMBE, W. A. M. DUNCAN, M. E. PARSONS SUMMARY x 10-'M on atrial muscle and 7,5 x lO-rM on uterine muscle. Even. at lO-'M, metiamide did not inhibit the A brief review of the pharmacology and toxicology of effects of isoprenaline on either of these tissues neither did it inhibit the effects of histamine on isolated Quinea- metiamide, a histamine H2-receptor antagonist, is given, ~ and evidence is presented to support the view that it pig ileum (mediated through H,-receptors). inhibits gastric acid secretion by virtue of its Hrreceptor Metiamide is also an inhibitor of gastric acid secretion. antagonist activity. Its effectiveness was estimated in two preparations: the Studies are also reported which show that metiamide lumen-perfused stomach of the anaesthetised rat' and given either intravenously or intraduodenally inhibits his the conscious Heidenhain pouch dog, prepared 1 - 3 years tamine- or pentagastrin-stimulated acid secretion in human before experimentation. Metiamide was given by rapid subjects. llltravenous injection during a maximal plateau of acid secretion stimulated by either histamine or pentagastrin, and the dose required to reduce this level of secretion by S. Afr. Med. J., 48, 2253 (1974). 50% (ED",) was estimated. The results are shown in Table I and indicate that the ED", values are very similar Conventional antihistaminic drugs, such as mepyramine. even in high concentrations, fail to inhibit histamine against those of both histamine and pentagastrin. Doses of stimulated gastric acid secretion. -

United States Patent (19) (11) 4,310,524 Wiech Et Al

United States Patent (19) (11) 4,310,524 Wiech et al. 45 Jan. 12, 1982 (54) TCA COMPOSITION AND METHOD FOR McMillen et al., Fed. Proc., 38,592 (1979). RAPD ONSET ANTDEPRESSANT Sellinger et al., Fed. Proc., 38,592 (1979). THERAPY Pandey et al., Fed. Proc., 38,592 (1979). 75) Inventors: Norbert L. Wiech; Richard C. Ursillo, Primary Examiner-Stanley J. Friedman both of Cincinnati, Ohio Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Millen & White 73) Assignee: Richardson-Merrell, Inc., Wilton, Conn. (57 ABSTRACT A method is provided for treating depression in a pa (21) Appl. No.: 139,498 tient therefrom and requiring rapid symptomatic relief, (22 Filed: Apr. 11, 1980 which comprises administering to said patient concur 51) Int. Cl. .................... A61K 31/33; A61K 31/135 rently (a) an effective antidepressant amount of a tricy clic antidepressant or a pharmaceutically effective acid (52) ...... 424/244; 424/330 addition salt thereof, and (b) an amount of an a-adrener 58) Field of Search ................................ 424/244, 330 gic receptor blocking agent effective to achieve rapid (56) References Cited onset of the antidepressant action of (a), whereby the PUBLICATIONS onset of said antidepressant action is achieved within Chemical Abst., vol. 66-72828m, (1967), Kellett. from 1 to 7 days. Chemical Abst, vol. 68-94371a, (1968), Martelli et al. A pharmaceutical composition is also provided which is Chemical Abst., vol. 74-86.048j, (1971), Dixit et al. especially adapted for use with the foregoing method. Holmberg et al., Psychopharm., 2,93 (1961). Svensson, Symp. Med. Hoechst., 13, 245 (1978). 17 Claims, No Drawings 4,310,524 1. -

Antagonism of Histamine-Activated Adenylate Cyclase in Brain by D

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol.74, No. 12, pp. 5697-5701, December 1977 Medical Sciences Antagonism of histamine-activated adenylate cyclase in brain by D-lysergic acid diethylamide (histaminergic antagonists/adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate/H2-receptors/ergots/D-2-bromolysergic acid diethylamide) JACK PETER GREEN, CARL LYNN JOHNSON, HAREL WEINSTEIN, AND SAUL MAAYANI Department of Pharmacology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine of the City University of New York, 100th Street and Fifth Avenue, New York, New- York 10029 Communicated by Vincent P. Dole, August 19, 1977 ABSTRACT D-Lysergic acid diethylamide and D-2-bro- (ED50; amount necessary to produce half-maximal response) molysergic acid diethylamide are competitive antagonists of and antagonist affinities (pA2) were not altered. the histamine activation of adenylate cyclase [ATP pyrophos- Adenylate Cyclase Assay. The assay system has been de- phate-lyase (cyclizing); E.C. 4.6.1.11 in broken cell preparations in All additions of the hippocampus and cortex of guinea pig brain. The ade- scribed (8). All assays were performed triplicate. nylate cyclase is linked to the histamine H2-receptor. Both D- were made to the assay tubes on ice. They were then transferred lysergic acid diethylamide and D-2-bromolysergic acid dieth- to a 30° shaking incubator and preincubated for 5 min to allow ylamide show topological congruency with potent H2-antago- the enzymatic activity to reach a steady state and to eliminate nists. D-2-Bromolysergic acid diethylamide is 10 times more the influence of any lag periods in hormone activation. After potent as an H2-antagonist than cimetidine, which has been the the preincubation period, 25 of [a-32PJATP (1-2 gCi) were most potent H2-antagonist reported, and D-lysergic acid di- pl ethylamide is about equipotent to cimetidine. -

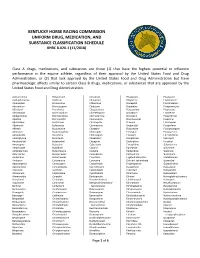

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Further Analysis of Anomalous Pkbvalues for Histamine

Br. J. Pharmac. (1985), 86, 581-587 Further analysis ofanomalous pKB values for histamine H2-receptor antagonists on the mouse isolated stomach assay J.W. Blackk, P. Leff* & N.P. Shankley The Rayne Institute, King's College Hospital Medical School, Denmark Hill, London SE5 8RX and Wellcome Research Laboratories*, Langley Court, Beckenham, Kent, BR3 3BS 1 Agonist-antagonist interactions at histamine receptors have been re-examined using improved techniques, on the mouse isolated, lumen-perfused, stomach gastric acid assay. 2 Using histamine as agonist, pKB values have been estimated for burimamide, metiamide, cimetidine, ranitidine, oxmetidine and famotidine on both the gastric and guinea-pig isolated right atrium assays. With the exception of oxmetidine on the atrial assay, these compounds behaved as competitive antagonists on both assays. 3 Oxmetidine significantly depressed basal rate on the atrial assay and the Schild plot slope parameter (0.81) was significantly less than one. 4 The pKB values estimated on the gastric assay were lower than those on the atrial assay. However, the difference between the values on the gastric and atrial assays was not constant. The difference between the two assays for famotidine was not significant. 5 We conclude that the apparent varying selectivity ofthe antagonists for gastric and atrial histamine H2-receptors may be explained by the differential loss ofantagonists into the gastric secretion from the receptor compartment and that there is no need to postulate heterogeneity ofhistamine H2-receptors. Introduction Angus & Black (1979) and Angus et al. (1980) found Pearce (1981) did not find a low pKB for metiamide that the histamine H2-receptor antagonists, using the rat isolated gastric mucosa preparation for burimamide, metiamide and cimetidine behaved as the assay. -

Rebound Intragastric Hyperacidity After Abrupt Withdrawal of Histamine

Gut, 1991,32, 1455-1460 1455 Rebound intragastric hyperacidity after abrupt withdrawal ofhistamine H2 receptor blockade Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.32.12.1455 on 1 December 1991. Downloaded from C U Nwokolo, J T L Smith, A M Sawyerr, R E Pounder Abstract an extensive research programme investigating In a series of 24 hour studies, intragastric the phenomenon of tolerance during continued acidity and plasma gastrin concentration were H2 blockade.'2 '4 measured simultaneously in 46 healthy sub- jects before, during, and 24 to 48 hours after abrupt withdrawal of a histamine H2 receptor Methods antagonist regimen. For 34 days subjects were given either cimetidine 800 mg at night (n=8), SUBJECTS AND DRUG REGIMENS ranitidine 150 mg twice daily (n= 10), ranitidine Forty six of48 healthy men completed the study. 300 mg at night (n= 12), nizatidine 300 mg at Their median age was 21 years (range 19 to 24 night (n=8), or famotidine 40 mg at night years), median weight was 74 kg (range 60 to 96 (n=8). All subjects responded to H2 blockade kg), and median height was 1'80 m (range 1.67 to by a decrease in 24 hour intragastric acidity. 1-93 m). Twenty four smoked cigarettes (4-20 Withdrawal ofH2 blockade resulted in a signifi- cigarettes per day). None had been dosed with an cant rise in median nocturnal integrated intra- antisecretory drug for at least eight weeks before gastric acidity in 42 of46 subjects (+36%; 95% entry to this study. CI +19, +55%) compared with prestudy This study was 'open label,' and all the H2 values, but this rise was not associated with a blockers were supplied by the pharmacy of the significant change in the median integrated Royal Free Hospital, London. -

Platelets by Burimamide G

Br. J. Pharmac. (1980), 71, 157-164 INHIBITION OF THROMBOXANE A2 BIOSYNTHESIS IN HUMAN PLATELETS BY BURIMAMIDE G. ALLAN, K.E. EAKINS*, P.S. KULKARNI* & R. LEVI Department of Pharmacology, Cornell University Medical College, New York, N.Y. and *Departments of Opthalmology and Pharmacology, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York, N.Y., U.S.A. 1 Burimamide selectively inhibited the formation of thromboxane A2 from prostaglandin endoper- oxides by human platelet microsomes in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 = 2.5 x 10-5 M). Burima- mide was found to be equipotent to imidazole as a thromboxane synthetase inhibitor. 2 Metiamide, cimetidine and a series of compounds either bearing a structural or pharmacological relationship to histamine caused little or no inhibition of thromboxane A2 biosynthesis by human platelet microsomes. 3 Burimamide (5 x 10-4 to 2.3 x 10- M) did not inhibit either the cyclo-oxygenase or the prosta- cyclin synthetase of sheep seminal vesicles or the prostacyclin synthetase of dog aortic microsomes. 4 Burimamide (2.5 x 10'- to 1.2 x 10-4 M) inhibited sodium arachidonate-induced human platelet aggregation; the degree of inhibition was dependent upon the concentration of arachidonic acid used to aggregate the platelets. Introduction The prostaglandin endoperoxides (prostaglandin G2, (Gryglewski, Zmuda, Korbut, Krecioch & Bieron, H2), the first cyclo-oxygenated products of arachido- 1977). nic acid metabolism can be converted enzymatically Various imidazole derivatives were studied by into either primary prostaglandins such as prosta- Moncada et al. (1977) and of these, only one-methyl glandin E2, F2, or D2, the non-prostanoate throm- imidazole was found to be a potent inhibitor of boxane A2 or prostacyclin (Moncada, Gryglewski, thromboxane A2 biosynthesis. -

Selective and Competitive Histamine H2-Receptor Blocking Effect of Famotidine on the Blood Pressure Response in Dogs and the Acid Secretory Response in Rats

Selective and Competitive Histamine H2-Receptor Blocking Effect of Famotidine on the Blood Pressure Response in Dogs and the Acid Secretory Response in Rats Keiji MIYATA, Takeshi KAMATO, Akira FUJIHARA and Masaaki TAKEDA Department of Pharmacology, Medicinal Research Laboratories I, Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 21 Miyukigaoka, Tsukuba , Ibaraki 305, Japan Accepted July 17, 1990 Abstract-Famotidine has been already demonstrated to be a competitive H2- receptor antagonist in the stomachs of dogs and cats. The present experiments were carried out to examine the effects of famotidine on changes in blood pressure induced by dimaprit and several other agonists in vagotomized, anesthetized dogs and on changes in gastric acid secretion induced by histamine in stomach-perfused, anesthetized rats. Famotidine caused a parallel displacement of the dimaprit dose-response curve to the right with a DR10 value of 0.059 ƒÊmol/kg, indicating that famotidine is 166 times more potent than cimetidine in vascular H2-blocking activity. On the contrary, famotidine did not affect the depressor responses to 2- pyridylethylamine and histamine that were antagonized by mepyramine. The histamine dose-response curve was displaced to the right more markedly after simultaneous administration of mepyramine and famotidine than after mepyramine alone. The effects of methacholine, phenylephrine and isoproterenol on blood pressure were not influenced by famotidine in doses up to 720 nmol/kg. In rats, famotidine also caused a parallel displacement of the acid dose-response curve to histamine to the right with a DR3 value of 24 ƒÊmol/kg/hr in stomach-perfused rats anesthetized with pentobarbital, exhibiting a potency 108 times greater than that of cimetidine. -

2 12/ 35 74Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 22 March 2012 (22.03.2012) 2 12/ 35 74 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 9/16 (2006.01) A61K 9/51 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 9/14 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/EP201 1/065959 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 14 September 201 1 (14.09.201 1) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (25) Filing Language: English RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (26) Publication Language: English TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 61/382,653 14 September 2010 (14.09.2010) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, NANOLOGICA AB [SE/SE]; P.O Box 8182, S-104 20 ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, Stockholm (SE). -

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY PROPERTY of RANITIDINE, a SPECIFIC Hz-RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY PROPERTY OF RANITIDINE, A SPECIFIC Hz-RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST M. D. PATWARDHAN, M. P. MULEY AND M. S. MANEKAR Department of Pharmacology, Govt. Medical College, Miraj - 416410 (MS) ( Received on October 24, 1985 ) Summary : The effects of ranitidine (2 mg/kg, po) and phenylbutazone (100 mg/kg po) have been studied in different models of acute and chronic inflammation in rats. Ranitidine showed significant anti-inflammatory activity in the four models used. This observation supports the concept that histamine has a pro-inflammatory role that is mediated via stimulation of HI receptors. Key words: ranitidine phenylbutazone anti -inflammatory INTRODUCTION Since Dale and Laidlaw's original observation in 1919 {4} that the local actions of histamine are similar to the inflammatory respon3e, the pos3ible involvement of histamine in inflammation is discussed extensively {12, 13}. Pelczarska (11) reported that hyposta mine, a histidine decarboxylase inhibitor reduced the inflammation and oedema associat ed with rat adjuvant arthritis. However, the 'classical' (Le.HI) antihistamines did not affect the severity of rat adjuvant arthritis even at very high dose levels {2}. The failure of the classical antihistamines to suppress many other inflammatory conditions has led investigators to suggest only a minor inflammatory role for histamine in acute inflamma tion (16). However, many actions of histamine which are resistant to the classical HI antihistaminics, have been shown to be blocked by the histamine Hz-antagonists (3). Our earlier observations (10) have suggested t:,e involvement of both HI and Hz receptors in the local actions of histamine Le. triple response. Hence it was thought worthwhile to study the role of Hz-receptors in different models of acute and chronic inflammation using the new, specific Hz-receptor antagonist, ranitidine. -

Histamine H2-Antagonists, Proton Pump Inhibitors and Other Drugs That Alter Gastric Acidity

Jack DeRuiter, Principles of Drug Action 2, Fall 2001 HISTAMINE H2-ANTAGONISTS, PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS AND OTHER DRUGS THAT ALTER GASTRIC ACIDITY I. Introduction Peptide ulcer disease (PUD) is a group of upper gastrointestinal tract disorders that result from the erosive action of acid and pepsin. Duodenal ulcer (DU) and gastric ulcer (GU) are the most common forms although PUD may occur in the esophagus or small intestine. Factors that are involved in the pathogenesis and recurrence of PUD include hypersecretion of acid and pepsin and GI infection by Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative spiral bacterium. H. Pylori has been found in virtually all patients with DU and approximately 75% of patients with GU. Some risk factors associated with recurrence of PUD include cigarette smoking, chronic use of ulcerogenic drugs (e.g. NSAIDs), male gender, age, alcohol consumption, emotional stress and family history. The goals of PUD therapy are to promote healing, relieve pain and prevent ulcer complications and recurrences. Medications used to heal or reduce ulcer recurrence include antacids, antimuscarinic drugs, histamine H2-receptor antagonists, protective mucosal barriers, proton pump inhibitors, prostaglandins and bismuth salt/antibiotic combinations. A characteristic feature of the stomach is its ability to secrete acid as part of its involvement in digesting food for absorption later in the intestine. The presence of acid and proteolytic pepsin enzymes, whose formation from pepsinogen is facilitated by the low gastric pH, is generally assumed to be required for the hydrolysis of proteins and other foods. The acid secretory unit of the gastric + + mucosa is the parietal (oxyntic) cell. -

Abnormal Functional and Morphological Regulation of the Gastric Mucosa in Histamine H2 Receptor–Deficient Mice

Abnormal functional and morphological regulation of the gastric mucosa in histamine H2 receptor–deficient mice Takashi Kobayashi, … , Susumu Okabe, Takeshi Watanabe J Clin Invest. 2000;105(12):1741-1749. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI9441. Article To clarify the physiological roles of histamine H2 receptor (H2R), we have generated histamine H2R-deficient mice by gene targeting. Homozygous mutant mice were viable and fertile without apparent abnormalities and, unexpectedly, showed normal basal gastric pH. However, the H2R-deficient mice exhibited a marked hypertrophy with enlarged folds in gastric mucosa and an elevated serum gastrin level. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased numbers of parietal and enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells. Despite this hypertrophy, parietal cells in mutant mice were significantly smaller than in wild-type mice and contained enlarged secretory canaliculi with a lower density of microvilli and few typical tubulovesicles in the narrow cytoplasm. Induction of gastric acid secretion by histamine or gastrin was completely abolished in the mutant mice, but carbachol still induced acid secretion. The present study clearly demonstrates that H2R-mediated signal(s) are required for cellular homeostasis of the gastric mucosa and normally formed secretory membranes in parietal cells. Moreover, impaired acid secretion due to the absence of H2R could be overcome by the signals from cholinergic receptors. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/9441/pdf Abnormal functional and morphological regulation of the gastric