“Cinema Is More Authoritarian Than Literature”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asdfgeneral Assembly

United Nations A/67/PV.12 General Assembly Offi cial Records asdfSixty-seventh session 12 th plenary meeting Thursday, 27 September 2012, 9 a.m. New York President : Mr. Jeremić . (Serbia) The meeting was called to order at 9.15 a.m. I also want to commend the Secretary-General for his tireless efforts to advance dialogue and cooperation, Address by His Excellency Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, and for his firm commitment to the core values and Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia principles of the United Nations. We in Bosnia and and Herzegovina Herzegovina recognize the importance of, and fully support, his action agenda, which identified five The President : The Assembly will hear an address generational imperatives: prevention, a more secure by the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and world, helping countries in transition, empowering Herzegovina. women and youth, and sustainable development. Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, Chairman of the Presidency Today’s world is the scene of unfolding crises and of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was escorted into the mounting global challenges. The first and foremost of General Assembly Hall. these is the disaster in Syria. As we stand here, our The President : On behalf of the General Assembly, fellow Syrians are fighting against a brutal regime. I have the honour to welcome to the United Nations His They are fighting to take their destiny into their own Excellency Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, Chairman of the hands. The regime of Bashar Al-Assad is answering Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to invite their yearning for freedom and democracy with guns him to address the Assembly. -

Filming Israel: a Conversation Author(S): Amos Gitai and Annette Michelson Source: October, Vol

Filming Israel: A Conversation Author(s): Amos Gitai and Annette Michelson Source: October, Vol. 98 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 47-75 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/779062 Accessed: 16-05-2017 19:51 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October This content downloaded from 143.117.16.36 on Tue, 16 May 2017 19:51:37 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Filming Israel: A Conversation AMOS GITAI and ANNETTE MICHELSON Amos Gitai, the preeminent Israeli filmmaker of his generation, is the author of thirty- seven films. Trained as an architect in Israel and at Berkeley, he turned in 1980 to filmmak- ingfor reasons set forth in the following portion of conversations held in New York in 2000. The radically critical dimension of his investigation of Israel's policy on the Palestinian question generated an immediate response of alarm, hostility, and censorship. Although the corpus of Gitai's work is large and extremely varied, including documentary films shot in the Far East, the Philippines, France, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere, it is largely the transition from work in the documentary mode to that of the fiction feature film that has, as might be expected, enlarged the appreciative audience of his work. -

Tard Exe:Plus Tard

IMAGE ET COMPAGNIE / AGAV FILMS / FRANCE 2 PRESENT ONE DAY YOU’LL UNDERSTAND DIRECTED BY AMOS GITAÏ BASED ON JÉRÔME CLÉMENT’S BOOK “PLUS TARD TU COMPRENDRAS” ome 20 years ago in an apartment overcrowded with antique objects, SRivka is trying to prepare dinner. But the Klaus Barbie trial on television breaks her concentration. Rivka is overcome with emotion listening to JÉRÔME CLÉMENT the testimony of a camp survivor. érôme Clément wrote Plus tard, tu comprendras (Grasset et Fasquelle, 2005) as an homage to his Jmother, whose parents were murdered at Auschwitz. Clément is also the author of several In Rivka's son Victor's office, the sounds of the trial are also heard. other books: Un homme en quête de vertu (Grasset, 1992), Lettres à Pierre Bérégovoy (Calmann Levy, Victor can't manage to fully concentrate on the piles of case documents on 1993), La culture expliquée à ma fille (Seuil, 1995) and Les femmes et l’amour (Stock, 2002). his desk nor his secretary's questions. Clément is currently elected President of the European television station Arte France. He’s also a board member of several cultural organizations (notably the Orchestre de Paris and Despite the intimacy of their mother-son dinner later that evening, the Théâtre du Châtelet). Clément has been decorated with the French Legion of Honor, the neither Rivka nor Victor speak of the Barbie trial. Rivka changes the subject National Order of Merit, the Society of Arts and Letters and Germany’s Grand Cross of the each time her son brings up the trial in conversation. -

The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society

The Myth of Defeat: The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society CHARLES S. LIEBMAN The Yom Kippur War of October 1973 arouses an uncomfortable feeling among Israeli Jews. Many think of it as a disaster or a calamity. This is evident in references to the War in Israeli literature, or the way in which the War is recalled in the media, on the anniversary of its outbreak. 1 Whereas evidence ofthe gloom is easy to document, the reasons are more difficult to fathom. The Yom Kippur War can be described as failure or defeat by amassing one set of arguments but it can also be assessed as a great achievement by marshalling other sets of arguments. This article will first show why the arguments that have been offered in arriving at a negative assessment of the War are not conclusive and will demonstrate how the memory of the Yom Kippur War might have been transformed into an event to be recalled with satisfaction and pride. 2 This leads to the critical question: why has this not happened? The background to the Yom Kippur War, the battles and the outcome of the war, lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. 3 Since these are part of the problem which this article addresses, the author offers only the barest outline of events, avoiding insofar as it is possible, the adoption of one interpretive scheme or another. In 1973, Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, fell on Saturday, 6 October. On that day the Egyptians in the south and the Syrians in the north attacked Israel. -

Judy Moseley Executive Director PIKUACH NEFESH

TEMPLE BETH-EL Congregation Sons of Israel and David Chartered 1854 Summer 2020 Sivan/Tammuz/Av 5780 THE SHOFAR Judy Moseley Executive Director PIKUACH NEFESH PIKUACH NEFESH, the principle of “saving a life,” is Temple Beth-El staff will begin to work in the building on a paramount in our tradition. It overrides all other rules, including rotating basis, and will work from our homes when necessary. We the observance of Shabbat. We have been consulting with some of will continue to be available to you through email and phone. the leading health institutions in our city, and they have been clear We will communicate any changes as appropriate. that one of the most important goals is to help “flatten the curve,” to We will be seek additional ways to build community in creative slow down the spread of the virus through social distancing, ways, taking advantage of technologies available to us, in which we thereby lessening the potential for overburdening our healthcare have invested. Please check your email for programming and systems. Given our tradition’s mandate to save lives above all other updates. mitzvot, the leadership team has made the very difficult decision to When I was younger and sneezed, my grandmother used to say, continue “virtual” services at this time. This is one of those moments “Gesundheit! To your good health.” I never really appreciated the when a community is tested, but can still provide sanctuary — even blessing embedded in that sentiment, but I offer it to all of you as we when we cannot physically be in our spiritual home. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Un Film De Amos Gitai

Agav Films présente Tsili Un film deAmos Gitai Adapté du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld AGAV FILMS présente “TSILI” un film deAmos GITAI avec Sarah ADLER, Meshi OLINSKI, Adam TSEKHMAN, Andrey KASHKAR, Yelena YARLOVA scénario Amos GITAI, Marie José SANSELME assistant réalisateur Adi HALFIN image Giora BEJACH décors Andrey CHERNEKOV son Tulli CHEN montage image Yuval ORR, Isabelle INGOLD musique Alexei KOCHETKOV, Amit KOTCHANSKY montage son Alex CLAUD producteurs exécutifs Gadi LEVY, Pavel DOUVIDZON producteurs Laurent TRUCHOT, Michael TAPUACH, Yuri KRESTINSKY, Denis FREYD, Amos GITAI producteurs associés Carlo HINTERMANN, Gerardo PANICHI, Luca VENITUCCI, Anton CHERENKOV, Anna SHALASHINA, Sam TSEKHMAN, Leon EDERY, Moshe EDERY coproduction AGAV Films, ARCHIPEL35, TRIKITA Entertainment, HAMON Hafakot, CITRULLO International Avec le support de ISRAEL FILM FUND, RUSSIAN CINEMA FUND distribution EPICENTRE FILMS (écriture blanc pour fond foncé) (écriture noire pour fond clair) (noir et blanc) (couleurs) AGAV FILMS présente Tsili Un film deAmos Gitai Adapté du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld Avec Sarah Adler, Meshi Olinski, Adam Tsekhman, Lea Koenig, Andrey Kashkar, Yelena Yaralova, Alexey Kochetkov 2014 - Israël / France / Italie / Russie - 88 min - Num - Couleur - 1.85 - Son 5.1 - Visa 135 578 Sortie nationale le 12 aout 2015 Matériel presse disponible sur www.epicentrefilms.com Distribution Presse EPICENTRE FILMS Florence Narozny Daniel Chabannes 6, place de la Madeleine 75008 Paris 55 rue de la Mare 75020 Paris Tél : 01 40 13 98 09 Tél. 01 43 49 03 03 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Inspiré du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld, le film retrace l’histoire de Tsili, une jeune fille prise dans les affres de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. -

Eine Lange Nacht Über Den Israelischen Filmemacher Amos Gitai

„Ich folge den Ablagerungen der Geschichte in mir“ Eine Lange Nacht über den israelischen Filmemacher Amos Gitai Autoren: Heike Brunkhorst und Roman Herzog Regie: Claudia Mützelfeldt Redaktion: Dr. Monika Künzel SprecherInnen: Renate Fuhrmann Volker Risch Josef Tratnik Nicole Engeln Uli Auer Sendetermine: Deutschlandfunk Kultur Deutschlandfunk __________________________________________________________________________ Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © Deutschlandradio - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - insofern zutreffend. 1. Stunde Atmozuspiel (Filmanfang Berlin-Jerusalem) Klaviermusik, Explosionen, Schüsse, Sirenen, Radiostimmen auf Hebräisch, Helikopterrotor. Zuspiel (Amos Gitai) A: «I consider that I am a witness, you know. Since my position during the Kippur war, I find myself as a witness…» E: «…And I think, that it deserves a strong cinema, not complaisant, not caressing, but engaging with this history.» Sprecher Josef Tratnik Ich denke, seit dem Jom-Kippur-Krieg bin ich ein Zeuge, der aufgrund merkwürdiger Umstände überlebt hat, als mein Helikopter abgeschossen wurde. Ich bin extrem interessiert, fasziniert und verstört von diesem Land. Und ich denke, es braucht ein starkes Kino, kein schmeichelndes oder wohlgefälliges, sondern ein Kino, das sich mit der Geschichte -

Amos Gitaï (1950-…)

Bibliothèque nationale de France direction des collections Juin 2016 département Arts du spectacle – Maison Jean Vilar AMOS GITAÏ (1950-…) Bibliographie sélective Amos Gitaï © Avshalom En 2015, Amos Gitaï a réalisé Le Dernier Jour d'Yitzhak Rabin. Le cinéaste israélien dépeint dans ce film les événements du 4 novembre 1995, jour où le Premier ministre d’Israël est assassiné par un jeune intégriste juif alors qu’il venait de terminer un discours faisant suite à une manifestation pour la paix et contre la violence à Tel-Aviv. Cet été 2016 au Festival d’Avignon, il mettra en scène avec Hanna Schygulla, le 10 juillet dans la Cour d’honneur du Palais des Papes, une version théâtrale de cette œuvre. A l’occasion du Festival d’Avignon, la bibliothèque de la Maison Jean Vilar, antenne du département des Arts du spectacle de la BnF, prépare une bibliographie complète des auteurs et artistes programmés. En avant-première, la bibliographie ci-dessous exclusivement consacrée à Amos Gitaï, liste ouvrages, articles, documents audiovisuels et autres documentations conservés par la bibliothèque de la Maison Jean Vilar et consultables gratuitement sur place par tous publics. La bibliographie envisage Amos Gitaï en tant que cinéaste et metteur en scène. Elle sera actualisée par de nouvelles acquisitions pour se fondre ultérieurement dans la bibliographie de l’ensemble des artistes et auteurs du festival 2016. A l’intérieur de chaque rubrique, les références sont classées par ordre chronologique 1 Amos Gitaï, cinéaste __________ Ananas. AB Productions ; France 3 Cinema, 1983. 1 DVD, durée 1h12. Maison Jean Vilar – magasin – [ADVD-445] __________ Le jardin pétrifié. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

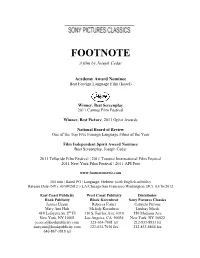

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

CFP: Thou Shalt Make Cinematic Images! Jewish Faith and Doubt on Screen (6/1/16; 10/26-30/16)

H-Film CFP: Thou Shalt Make Cinematic Images! Jewish Faith and Doubt on Screen (6/1/16; 10/26-30/16) Discussion published by Cynthia Miller on Friday, March 18, 2016 CALL FOR PAPERS CFP: Thou Shalt Make Cinematic Images! Jewish Faith and Doubt on Screen An area of multiple panels for the 2016 Film & History Conference: Gods and Heretics: Figures of Power and Subversion in Film and Television October 26-October 30, 2016 The Milwaukee Hilton Milwaukee, WI (USA) DEADLINE for abstracts: June 1, 2016 AREA: Thou Shalt Make Cinematic Images! Jewish Faith and Doubt on Screen Despite Judaism’s commandment against making graven images of God, films representing Jewish faith in God—or doubt in the face of collective and personal catastrophes and competing worldviews—have abounded from the advent of the movie industry. Since God cannot be visualized, movies must rely on depictions of an omnipotent historical and moral force, or a source of belief compelling Jews to endure martyrdom, persecution, and segregation, and to observe Jewish law and rituals. Motion pictures about how God informs modern Jewish lives have become more varied with the emergence of Jewish denominationalism and secular ideologies, like socialism or Zionism, often pitting factions within the Jewish community against each other. This area welcomes papers and panels that explore how Jewish belief and disbelief in God are constructed by filmmakers in documentaries and feature movies. The following themes are suggestions and should not be construed as the only topics that would fit in this area: The portrayal of Judaism in documentaries: Heritage: Civilization and the Jews (1984), A Life Apart (1997), and The Story of the Jews (2013).