Filming Israel: a Conversation Author(S): Amos Gitai and Annette Michelson Source: October, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asdfgeneral Assembly

United Nations A/67/PV.12 General Assembly Offi cial Records asdfSixty-seventh session 12 th plenary meeting Thursday, 27 September 2012, 9 a.m. New York President : Mr. Jeremić . (Serbia) The meeting was called to order at 9.15 a.m. I also want to commend the Secretary-General for his tireless efforts to advance dialogue and cooperation, Address by His Excellency Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, and for his firm commitment to the core values and Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia principles of the United Nations. We in Bosnia and and Herzegovina Herzegovina recognize the importance of, and fully support, his action agenda, which identified five The President : The Assembly will hear an address generational imperatives: prevention, a more secure by the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and world, helping countries in transition, empowering Herzegovina. women and youth, and sustainable development. Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, Chairman of the Presidency Today’s world is the scene of unfolding crises and of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was escorted into the mounting global challenges. The first and foremost of General Assembly Hall. these is the disaster in Syria. As we stand here, our The President : On behalf of the General Assembly, fellow Syrians are fighting against a brutal regime. I have the honour to welcome to the United Nations His They are fighting to take their destiny into their own Excellency Mr. Bakir Izetbegović, Chairman of the hands. The regime of Bashar Al-Assad is answering Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to invite their yearning for freedom and democracy with guns him to address the Assembly. -

Tard Exe:Plus Tard

IMAGE ET COMPAGNIE / AGAV FILMS / FRANCE 2 PRESENT ONE DAY YOU’LL UNDERSTAND DIRECTED BY AMOS GITAÏ BASED ON JÉRÔME CLÉMENT’S BOOK “PLUS TARD TU COMPRENDRAS” ome 20 years ago in an apartment overcrowded with antique objects, SRivka is trying to prepare dinner. But the Klaus Barbie trial on television breaks her concentration. Rivka is overcome with emotion listening to JÉRÔME CLÉMENT the testimony of a camp survivor. érôme Clément wrote Plus tard, tu comprendras (Grasset et Fasquelle, 2005) as an homage to his Jmother, whose parents were murdered at Auschwitz. Clément is also the author of several In Rivka's son Victor's office, the sounds of the trial are also heard. other books: Un homme en quête de vertu (Grasset, 1992), Lettres à Pierre Bérégovoy (Calmann Levy, Victor can't manage to fully concentrate on the piles of case documents on 1993), La culture expliquée à ma fille (Seuil, 1995) and Les femmes et l’amour (Stock, 2002). his desk nor his secretary's questions. Clément is currently elected President of the European television station Arte France. He’s also a board member of several cultural organizations (notably the Orchestre de Paris and Despite the intimacy of their mother-son dinner later that evening, the Théâtre du Châtelet). Clément has been decorated with the French Legion of Honor, the neither Rivka nor Victor speak of the Barbie trial. Rivka changes the subject National Order of Merit, the Society of Arts and Letters and Germany’s Grand Cross of the each time her son brings up the trial in conversation. -

The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society

The Myth of Defeat: The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society CHARLES S. LIEBMAN The Yom Kippur War of October 1973 arouses an uncomfortable feeling among Israeli Jews. Many think of it as a disaster or a calamity. This is evident in references to the War in Israeli literature, or the way in which the War is recalled in the media, on the anniversary of its outbreak. 1 Whereas evidence ofthe gloom is easy to document, the reasons are more difficult to fathom. The Yom Kippur War can be described as failure or defeat by amassing one set of arguments but it can also be assessed as a great achievement by marshalling other sets of arguments. This article will first show why the arguments that have been offered in arriving at a negative assessment of the War are not conclusive and will demonstrate how the memory of the Yom Kippur War might have been transformed into an event to be recalled with satisfaction and pride. 2 This leads to the critical question: why has this not happened? The background to the Yom Kippur War, the battles and the outcome of the war, lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. 3 Since these are part of the problem which this article addresses, the author offers only the barest outline of events, avoiding insofar as it is possible, the adoption of one interpretive scheme or another. In 1973, Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, fell on Saturday, 6 October. On that day the Egyptians in the south and the Syrians in the north attacked Israel. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

Un Film De Amos Gitai

Agav Films présente Tsili Un film deAmos Gitai Adapté du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld AGAV FILMS présente “TSILI” un film deAmos GITAI avec Sarah ADLER, Meshi OLINSKI, Adam TSEKHMAN, Andrey KASHKAR, Yelena YARLOVA scénario Amos GITAI, Marie José SANSELME assistant réalisateur Adi HALFIN image Giora BEJACH décors Andrey CHERNEKOV son Tulli CHEN montage image Yuval ORR, Isabelle INGOLD musique Alexei KOCHETKOV, Amit KOTCHANSKY montage son Alex CLAUD producteurs exécutifs Gadi LEVY, Pavel DOUVIDZON producteurs Laurent TRUCHOT, Michael TAPUACH, Yuri KRESTINSKY, Denis FREYD, Amos GITAI producteurs associés Carlo HINTERMANN, Gerardo PANICHI, Luca VENITUCCI, Anton CHERENKOV, Anna SHALASHINA, Sam TSEKHMAN, Leon EDERY, Moshe EDERY coproduction AGAV Films, ARCHIPEL35, TRIKITA Entertainment, HAMON Hafakot, CITRULLO International Avec le support de ISRAEL FILM FUND, RUSSIAN CINEMA FUND distribution EPICENTRE FILMS (écriture blanc pour fond foncé) (écriture noire pour fond clair) (noir et blanc) (couleurs) AGAV FILMS présente Tsili Un film deAmos Gitai Adapté du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld Avec Sarah Adler, Meshi Olinski, Adam Tsekhman, Lea Koenig, Andrey Kashkar, Yelena Yaralova, Alexey Kochetkov 2014 - Israël / France / Italie / Russie - 88 min - Num - Couleur - 1.85 - Son 5.1 - Visa 135 578 Sortie nationale le 12 aout 2015 Matériel presse disponible sur www.epicentrefilms.com Distribution Presse EPICENTRE FILMS Florence Narozny Daniel Chabannes 6, place de la Madeleine 75008 Paris 55 rue de la Mare 75020 Paris Tél : 01 40 13 98 09 Tél. 01 43 49 03 03 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Inspiré du roman d’Aharon Appelfeld, le film retrace l’histoire de Tsili, une jeune fille prise dans les affres de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. -

Eine Lange Nacht Über Den Israelischen Filmemacher Amos Gitai

„Ich folge den Ablagerungen der Geschichte in mir“ Eine Lange Nacht über den israelischen Filmemacher Amos Gitai Autoren: Heike Brunkhorst und Roman Herzog Regie: Claudia Mützelfeldt Redaktion: Dr. Monika Künzel SprecherInnen: Renate Fuhrmann Volker Risch Josef Tratnik Nicole Engeln Uli Auer Sendetermine: Deutschlandfunk Kultur Deutschlandfunk __________________________________________________________________________ Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © Deutschlandradio - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - insofern zutreffend. 1. Stunde Atmozuspiel (Filmanfang Berlin-Jerusalem) Klaviermusik, Explosionen, Schüsse, Sirenen, Radiostimmen auf Hebräisch, Helikopterrotor. Zuspiel (Amos Gitai) A: «I consider that I am a witness, you know. Since my position during the Kippur war, I find myself as a witness…» E: «…And I think, that it deserves a strong cinema, not complaisant, not caressing, but engaging with this history.» Sprecher Josef Tratnik Ich denke, seit dem Jom-Kippur-Krieg bin ich ein Zeuge, der aufgrund merkwürdiger Umstände überlebt hat, als mein Helikopter abgeschossen wurde. Ich bin extrem interessiert, fasziniert und verstört von diesem Land. Und ich denke, es braucht ein starkes Kino, kein schmeichelndes oder wohlgefälliges, sondern ein Kino, das sich mit der Geschichte -

El NORA ALILA (God of Might, God of Awe)- from Spain to the Four

El NORA ALILA (God of Might, God of Awe) From Spain to the Four Corners of the Earth Avner Bahat Thc Golden Age of Hebrew Poetry in Spain Moses lbn Ezra Yom Kippur--Nei 'la God of Might- The poem: Rhyming. structure. meter Geographical Di!>persion The Music: E,·idence!> in Notation., The Music: Recording~ Transcription~ h E GoLDEN Age of Judai.,m in Spain had witnessed The Hcbrew poet!. also emplo)cd a meter of 'long' the creation of Hebrew poetry unpreccdented in both syllables. avoiding thc 'hort onei. altogether (mishkal quantity and quality. unparalleled by an) thing since lwtenu 'ot). [... 1They developcd a ~yllab i c meter. based on biblical time'> through to modem times. The Hebrew a regular nurnber of ~yllablei. per Iíne (6 or 8). which poetry in Spain ha'> been intluenceJ by Arab poetry allowcd the free u~e of ~hort vowcls but disregarded them ai. ~yllable!> . (ldcm). in terms of rhyming. meter~. forms ami contents. encompassing secular and liturgical poetry. Thc number of voweb. pcr linc was constam. and the "hort onc!., shw1 an<l hawJ: wcrc not countcd. so The HcbrC\\ poetr) that floumhed in Spain from the tenth thal these were actually !.yllables in the mouern . ense to the fiftcenth ccntuf) \\ª' ha-,ed on thc Arabíc ~):.tem of of thc tcnn. poetic-. adapted to the Hebrc"' language. In <,ecular poetry the meter\\ª' quantitative. i.e. there wa-, a pattcm of long Onc of thc 1110\t common forms in Arab poetry is muwasllslwll, sllir e-:.or and !>hort '>) llablc-, throughout a líne repeated in ali the the or in Hebrew (a girdlc line<, of a pO\'!rn ('>imilar to thc '>ptcm u'ed in clas,ical poem). -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

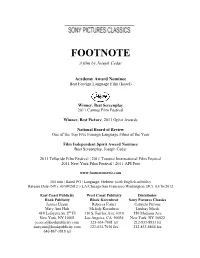

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

High Holy Days 5778

High Holy Days 5778 Tishre 5778 Fall 2017 Kahal Joseph Congregation Los Angeles California This Booklet is Dedicated in Memory of Anita Wozniak Hana bat Haviva, z’’l 1961-2017 May the community she loved so much shine through the pages in your hands. Table of Contents Dedication to Anita Wozniak .............................................. 2 Guide to Prayer Services .................................................... 4 Rabbi Raif Melhado’s Message .......................................... 6 President Yvette Dabby’s Message ................................... 7 A Letter from Ron Einy, Chairperson ................................ 9 A Letter from Michelle Kurtz, VP of Membership ............ 10 KJ Holiday Schedule Rosh Hashana ........................................................... 11 Yom Kippur ................................................................ 13 Sukkot ........................................................................ 14 Simhat Torah .............................................................. 16 Introducing our Clergy ..................................................... 18 What is Rosh Hashana? ................................................... 20 What is Yom Kippur? ........................................................ 22 History of Iraqi & Persian Jews ........................................ 24 History of Kahal Joseph ................................................... 26 Preserving Iraqi Heritage .................................................. 28 The Selihot Prayers in English Letters ........................... -

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART to LIFE By

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART TO LIFE by KATHERINE E. FLACH Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Dr. Constantine Petridis, Co-Advisor Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Katherine E. Flach ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Catherine B. Scallen (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Constantine Petridis ________________________________________________ Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Jonathan Sadowsky ________________________________________________ DATE OF DEFENSE March 4, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 This dissertation is dedicated to my family John, Linda, Liz and Sam 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 11 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 12 Eliot Elisofon and African Art: An Introduction ........................................................ 14 Elisofon and LIFE ...................................................................................................... -

The Law of the Pursuer

Gitai,LAW OF Amos THE PURSUER 03121 pos: 68 © Amos Gitai The Law of the Pursuer Amos Gitai 2017. essay exhibition. Curatorial Team Elena Agudio, Antonia The Law of the Pursuer is an essay exhibition by Amos Gitai Alampi, Abhishek Nilamber. Commissioned by SAVVY Contemporary. revolving around some of the issues and themes raised in his film, Rabin, the Last Day (2015), about the assassination of the Israeli Contact: http://www.savvy-contemporary.com Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on 4 November 1995. Featuring unreleased research material and film footage from Gitai’s archive and collected over the course of the last twenty years, the exhibition’s central piece is a new video installation with a performative element commissioned by SAVVY Contemporary questioning the shifting concept of democracy and addressing the problem of extremisms and the current crisis of politics. Resonating with the structure of the film, his installation is a whirlwind of discourse surrounding the terrible and confounding act of violence that took place in Tel Aviv, while also becoming a metaphor of the consequences of a polarized and poisonous atmosphere of political extremism. The Law of the Pursuer shows how inflammatory and fundamentalist language can instill violence and sow the seeds of brutality, it is an examination and a psychoanalytical portrait of a traumatized political context and society speaking to the one we are living in today. berlinale forum expanded 2017 177 Amos Gitai, born in 1950 in Haifa, Israel, is a filmmaker based in Paris and Haifa, mainly known for making documentaries and feature films dealing with the Middle East and the Jewish-Arab conflict. -

Spring 2021 MARCH 15 to MAY 7 General Information

USM Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Class Schedule Spring 2021 MARCH 15 TO MAY 7 General Information If you are 50 or older, with a curious mind and an interest in learning just the fiscal year from July 1 to June 30. Your annual membership allows you for the joy of it, we invite you to join 2,200-plus like-minded older learners to participate in all OLLI at USM courses and Special Interest Groups at who are members of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI). OLLI OLLI. Our monthly online newsletter and Facebook page outline upcoming is located on the Portland campus of the University of Southern Maine. programs and events open to you. OLLI at USM is committed to providing its members with a wide variety of stimulating courses, lectures, workshops, and complementary activities in a Scholarships creative and inclusive learning community. Full and partial scholarships are available through a simple, friendly, As an OLLI member at USM, you’ll choose from an extensive array of confidential process. Scholarships are limited to $50 per person per term, peer-taught courses in the liberal arts and sciences. There are no entrance applicable to one course, the SAGE program, or workshops. Scholarships requirements, grades, or tests. Your experience and love of learning are do not apply to OLLI at USM membership, trips, or special events. what count. Some OLLI at USM classes involve homework—usually reading Scholarship applications can be downloaded from the OLLI website: or honing skills taught in class. Assignments are not mandatory but can usm.maine.edu/olli/olli-scholarships.