Looking Back on October, 1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stalinism and Trotskyism in Vietnam

r Telegram: Defend the DRV-NLF! The following telegram was sent as the u.s. imperialists mined Haiphong harbor and the North Vietnamese coast. At the time Soviet bureaucrats were preparing to receive Nixon in Moscow just as their Chinese counterparts a few months earlier wined and dined him in Peking as he terror-bombed Vietnam. Embassy of the U.S.S.R. Washington, D.C. U.N. Mission of the People's Republic of China New York, N.Y. On behalf of the urgent revolutionary needs of the international working class and in accord with the inevitable aims of our future worker~ government in the United States, we demand that you immediately expand shipment of military supplies of the highest technical quality to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and that you offer the DRV the fullest all sided assistance including necessary Russian-Chinese joint military collaboration. No other course will serve at this moment of savage imperialist escalation against the DRV and the Indochinese working people whose military victories have totally shattered the myths of the Vietnamization and pacification programs of Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon. signed: Political Bureau, Spartacist League of the U.S. 8 May 1972 copies to: D RV and N LF delegations, Paris -from Workers Vanguard No.9, June 1972 6 n p Stalinism and Trotskyism In• Vietnam ~···· l,~ ~ r SPARTACIST PUBLISHING co. Box 1377, G.P.O. New York, N.Y. 10001, U.S.A . • December 1976 Ho Chi Minh Ta Thu Thau CONTENTS CHAPTER I In Defense of Vietnamese Trotskyism (I:·: • >'~ Stalinism and Trotskyism in Vietnam ................... -

History of the Class Struggle in Hungary 1919-1945

Barricade Collective History of the class struggle in Hungary 1919-1945 The period of retorsion As the part of the breaking down of the 1917-23 revolutionary wave the bourgeoisie used very manifold means, took advantage of the weaknesses of the proletariat, to beat back the proletarian revolution in Hungary. When the self-organizing proletariat was actively fighting against the imperialist war by force of arms, organizing extended strike movement, forming workers’ councils, looting, as well as started the liquidation of the bourgeoisie, a “radical” framing force was needed which could counteract the extension and centralization of the struggles, the organization of the proletariat as a party. This role was played by the Bolshevik movement which, in spite of that it gained its strength mainly from the proletariat and its leadership, in words, was for the revolution (of course it wanted to carry out the revolution by the specific Bolshevik scheme: it sought to withdraw the old ruling class in order that it could establish the radical social democratic form of capitalism controlled by the Bolsheviks), during the period of deap crisis of capital, when there were good conditions for proletarian self-organization and for the total destruction of capitalist structures, it was objectively counter- revolutionary. The Bolsheviks backed by the moderate social democrats established the so-called Hungarian Council Republic, a structure of power which was able to successfully counteract the radicalisation of the masses. Under their reign the Bolshevik leadership was acting the part of the grave-digger of the struggling proletariat and doing so encouraged the sweep of the counter-revolution. -

Revolutionary Marxism 2019 Special Annual English Edition

Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement. V. I. Lenin, What is to be done? Revolutionary Marxism 2019 Special annual English edition www.devrimcimarksizm.net [email protected] Devrimci Marksizm Üç aylık politik/teorik dergi (Yerel, süreli yayın) İngilizce yıllık özel sayı Sahibi ve Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü: Şiar Rişvanoğlu Yönetim Yeri: Adliye Arkası 3. Sokak Tüzün İşhanı No: 22/2 ADANA Baskı: Net Copy Center, Özel Baskı Çözümleri, Ömer Avni Mh., İnönü Cad./ Beytül Malcı Sok. 23/A, 34427 Beyoğlu/İstanbul Tel: +90-4440708 Yurtdışı Fiyatı: 10 Avro Kıbrıs Fiyatı: 20 TL Fiyatı: 15 TL (KDV Dahil) Cover Photo Soviet troops examining the fallen eagle – the symbol of Nazism (Berlin, 1945). Revolutionary Marxism 2019 CONTENTS In this issue 5 Fascism Sungur Savran The return of barbarism: Fascism in the 21st 15 century (1): Historical roots: classical fascism Mustafa Kemal Coşkun Is fascism a non-class ideology? 49 Turkey Kurtar Tanyılmaz Turkey’s economic crisis 55 Topics in the history of socialism Armağan Tulunay The greatest revolutionary woman in 69 history: Rosa Luxemburg Burak Gürel The road to capitalist restoration in the 85 People’s Republic of China: Maoism, bureaucracy, and mass movements Celia Hart Welcome … Trotsky 109 Sungur Savran Captive Bolshevik: Nâzım Hikmet and 119 Stalinism 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution Praxis Collective How did the Iranian revolution transmute? 145 Araz Bağban A revolution between two dictatorships 159 Network of Marxist journals Tamás Krausz The Hungarian Soviet Republic from a 179 century-long perspective Katerina Matsa October 1917 and the everyday life of the 185 Soviet masses Jock Palfreeman Marx and human rights 197 In this issue More than ten years have passed since the collapse of the US financial system and the beginning of the Third Great Depression of capitalism. -

Redalyc.Lenin and the National Question. Beyond Essentialism And

Nómadas ISSN: 1578-6730 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Castien Maestro, Juan Ignacio Lenin and the national question. Beyond essentialism and constructionism Nómadas, vol. 49, 2016 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=18153282004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Nómadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas Volumen Especial: Mediterranean Perspectives | 49 (2016) LENIN AND THE NATIONAL QUESTION. BEYOND ESSENTIALISM AND CONSTRUCTIONISM * Juan Ignacio Castien Maestro Complutense University of Madrid *Translated into english by Rodrigo Benito García-Retamero http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/NOMA.53536 Abstract.- Lenin's analysis of the 'national question' shows numerous virtualities from a theoretical and political perspective. We are going to examine some of the theoretical conceptions which seem to underlie his view on the national question. In our opinion, these conceptions are a commendable work since they represent an alternative to the dilemma of essentialism and constructivism through which the social contemporary thinking has often fluctuated. Whereas essentialism tends to consider the national fact as a reality by nature and since time immemorial, constructionist approaches like those of Benedict Anderson and Ernest Gellner have insisted on its relatively recent political construction nature. Despite its unquestionable merits, this approach has often fallen into an excessively artificial perspective. According to it, the fabrication of any national identity would be possible with the appropriate skills to do so. -

The Bolsheviks and War

The Bolsheviks and War By Sam Marcy [1985] Lessons for today's anti-war movement Marxists Internet Archive The Bolsheviks and War – Lessons for Today’s Anti-war movement 2 The Bolsheviks and War – Lessons for Today’s Anti-war movement Introduction 5 I. The Bolsheviks and World War I 1. Social Democracy and the approaching war 9 2. Zimmerwald: The internationalists regroup 20 3. Lenin's response to the war 28 II. Lessons for Today's Anti-war Movement 4. Imperialism and the growth of opportunism 48 5. Class struggle in the nuclear age 67 6. The Green Corn Rebellion and the struggle for socialism 95 Appendices Appendix I: Stuttgart Resolution 124 Appendix II: Basel Manifesto 128 Appendix III: International Socialist Women's Conference(Berne) 135 Appendix IV: Zimmerwald Manifesto 138 Appendix V: Zimmerwald Declaration of sympathy 144 Appendix VI: Draft resolution from leftwing at Zimmerwald 146 Appendix VII: Draft Manifesto introduced at Zimmerwald 149 Appendix VIII: Two Declarations made at Zimmerwald 153 Appendix IX: War proclamation & program, Socialist Party(April, 1917) 155 Appendix X: Decree on Peace by Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets 162 3 The Bolsheviks and War – Lessons for Today’s Anti-war movement 4 The Bolsheviks and War – Lessons for Today’s Anti-war movement Introduction For those who wish to study more about the struggle against the frst imperialist world war, there are the classics written by Lenin at the time, including his Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism, and Socialism and War. These works are generally available in bookstores, particularly those specializing in Marxist literature. -

Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse

"Order, Authority, Nation": Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse by Mathieu Hikaru Desan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor George Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard Brick Assistant Professor Robert S. Jansen Emeritus Professor Howard Kimeldorf Professor Gisèle Sapiro Centre national de la recherche scientifique/École des hautes études en sciences sociales Acknowledgments Scholarly production is necessarily a collective endeavor. Even during the long isolated hours spent in dusty archives, this basic fact was never far from my mind, and this dissertation would be nothing without the community of scholars and friends that has nourished me over the past ten years. First thanks are due to George Steinmetz, my advisor and Chair. From the very beginning of my time as a graduate student, he has been my intellectual role model. He has also been my champion throughout the years, and every opportunity I have had has been in large measure thanks to him. Both his work and our conversations have been constant sources of inspiration, and the breadth of his knowledge has been a vital resource, especially to someone whose interests traverse disciplinary boundaries. George is that rare sociologist whose theoretical curiosity and sophistication is matched only by the lucidity of this thought. Nobody is more responsible for my scholarly development than George, and all my work bears his imprint. I will spend a lifetime trying to live up to his scholarly example. I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. -

A Century of Conflict: Communist Techniques of World Revolution

Chart 1. THE TRIPLE CHAIN OF COMMAND OF COMMUNIST POWER* * ln 1952 , the politburo was renamed " praesidium ," and orgburo and secretariat were merged . The future will tell the signiflcance of this change . Chart Il. THE FLOWER STRUCTURE OF COMMUNIST ORGANIZATIONS FRONT ORG. The lnterlocking System of Communist Party , Parly Auxil ia ries , Front Organizations, and Transmission Belts A Century of Conflict Communist Techniques of World Revolution A CENTURY OF CONFLICT Communist Techniques of World Revolution STEFAN T. POSSONY Professor of International Politics Georgetown University Chicago • HENRY REGNERY COMPANY • 1953 Copyright 1953 HENRY REGNERY COMPANY Chicago, Illinois Charts by Les Rosenzweig Manufactured in the United States of America Preface LEPURPOSE of this book is to present the soviet pattern of conquest. The method of this book is to trace the development of the com munist doctrine of conflict management . A synthesis of the bolshevik "science of victory" concludes the volume. Communist techniques of usurpation and expansion represent the culmination of a co-ordinated effort by several generations of skilled revolutionaries and soldiers. These methods, which reflect the politi cal, social, and military experience of previous conquerors, are based upon elaborate studies in the humanities and social sciences as well as upon extensive pragmatic tests. So far, communist conflict management-poorly imitated by the nazis-has stood the test of victory as well as that of defeat and catastrophe. The writer submits that the successful soviet encroach ment on the free world is due largely to the operational know-how of the communists. Marxian communism has been an important political movement since 1848. -

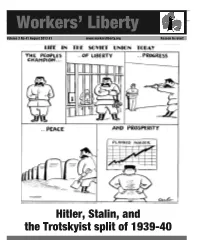

Hitler, Stalin, and the Trotskyist Split of 1939-40 the Trotskyist Split of 1939-40

The Trotskyist split of 1939-40 Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 41 August 2013 £1 www.workersliberty.org Reason in revolt Hitler, Stalin, and the Trotskyist split of 1939-40 The Trotskyist split of 1939-40 From 1935: the official Communist Parties across the world, and Stalin’s Russian government, agitate for an alliance of “the democracies” (taken to include Reclaiming our history Russia) By Sean Matgamna Yugoslavia, and looked to the USSR, under the Stalinist bu - 23 August 1939: “Hitler-Stalin pact” signed between reaucracy, to lead a great world-wide revolution against cap - Nazi Germany and Russia. George Santanyana’s aphorism, “Those who do not learn italism in the course of the World War 3 which they saw as from history are likely to repeat it”, is not less true for having inevitable. The Trotskyists had become “Brandlerites”. 1 September 1939: Germany invades Poland. Russia become a cliché. And those who do not know their own his - In the 1960s the British SWP prided itself on not being will invade from the east on 17 September. Hitler and tory cannot learn from it. Leninist, which it explained as not being like the Healy or - Stalin agree to partition Poland The history of the Trotskyist movement — that is, of or - ganisation. In the 1970s it was transformed into a “Leninist” ganised revolutionary Marxism for most of the 20th century organisation and into an organisation more like the Healyites 3 September 1939: Britain and France declare war — is a case in point. To an enormous extent the received his - of the 1960s than its old self. -

Vladimir Ilich Lenin

Overview - Vladimir Lenin Vladimir Ilich Lenin Encyclopedia of World Biography, December 12, 1998 Born: April 10, 1870 in Ulianovsk, Russia Died: January 21, 1924 in Moscow, Soviet Union Other Names: Lenin, Vladimir I.; Lenin, V.I.; Lenin, Vladimir Ilich; Lenin, Vladimir Illyich; Ulyanov, Vladimir I.; Lenin, Vladimir Ilych; Lenin, Nikolai; Ulyanov, Vladimir Illyich; Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich; Richter, Joseph; Ulyanov, Vladimir Ilyich; Lenin, N.; Ulyanov, V.I.; Ulyanov- Lenin; Lenin, Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov Nationality: Soviet Occupation: Head of state The Russian statesman Vladimir Ilich Lenin (1870-1924) was the creator of the Bolshevik party, the Soviet state, and the Third International. He was a successful revolutionary leader and an important contributor to revolutionary socialist theory. Few events have shaped contemporary history as profoundly as the Russian Revolution and the Communist revolutions that followed it. Each one of them was made in the name of V. I. Lenin, his doctrines, and his political practices. Contemporary thinking about world affairs has been greatly influenced by Lenin's impetus and contributions. From Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points to today's preoccupation with wars of national liberation, imperialism, and decolonization, many important issues of contemporary social science were first raised or disseminated by Lenin; even some of the terms he used have entered into everyone's vocabulary. The very opposition to Lenin often takes Leninist forms. Formative Years V. I. Lenin was born in Simbirsk (today Ulianovsk) on April 10 (Old Style), 1870. His real family name was Ulianov, and his father, Ilia Nikolaevich Ulianov, was a high official in the czarist educational bureaucracy who had risen into the nobility. -

Communism and Social Democracy

COMMUNISM AND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY PART I A HISTORY OF SOCIALIST THOUGHT: Volume IV, Part I COMMUNISM AND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY 1914-1931 BY G. D. H. COLE LONDON M A C M IL L A N & CO L T D NEW YORK • ST MARTIN’S PRESS 1958 Copyright © G. D. H. Cole 1958 MACMILLAN AND COMPANY LIMITED London Bombay Calcutta Madras Melbourne THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA LIMITED Toronto ST MARTIN’S PRESS INC New York PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE h a v e again to acknowledge the ungrudging help given me by many friends in the making of this volume. Three Ipersons for whose judgment I have a high respect — Mr. H. N. Brailsford, Professor Sir Isaiah Berlin, and Mr. Julius Braunthal — read through the entire manuscript and gave me advice that led me to make many corrections and modifications in the opinions expressed. I am again most grateful to them all. I have also many other persons to thank for help with particular chapters, especially in filling in missing dates of births and deaths — for I attach considerable importance to knowing how old my characters were when they did anything worthy of note. Among those who helped me in this respect are M. J. Maitron of the Institut Franyais D ’Histoire Sociale and M. Maurice Dommanget, for France; Dr. Gerhard Gleissberg and Frau Ruth Gleissberg, for Germany ; Mr. Lloyd Ross, for Australia ; Dr. J. P. L. Wiessing, for Holland ; M. Rene Renard, for Belgium ; Mr. Branko Pribicevic, for Yugoslavia ; Mr. S. K. Evangelides, for Greece ; Professor Iwao Ayusawa, for Japan ; Senor Luis Henriquez, for Chile ; Mr. -

Against Trotskyism

INSTITUTE OF MARXISM-LENINISM OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE CPSU AGAINST TROTSKYISM THE STRUGGLE OF LENIN AND THE CPSU AGAINST TROTSKYISM A Collection of Documents PROGRESS PUBLISHERS Moscow PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The works of Lenin (in their entirety or extracts) and the decisions adopted at congresses and conferences of the Bolshevik Party and at plenary meetings of the CC offered in this volume show that Trotskyism is an anti-Marxist, opportunist trend, show its subversive activities against the Communist Party and expose its ties with the opportunist leaders of the Second International and with revisionist, anti-Soviet trends and groups in the workers’ parties of different countries. The resolutions passed by local Party organisations underscore the CPSU’s unity against Trotskyism. The addenda include - decisions adopted by the Communist International and resolutions of the Soviet trade unions against Trotskyism. The Notes facilitate the use of the material published in this book. First printing 1972 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics FOREWORD 1 LENIN’S CRITICISM OF THE OPPORTUNIST VIEWS OF THE 8 TROTSKYITES AND EXPOSURE OF THEIR SUBVERSIVE ACTIVITIES IN 1903-1917 SECOND CONGRESS OF THE RSDLP. July 17 (30)—August 10 (23), 1903 8 EXTRACTS FROM SPEECHES ON THE DISCUSSION OF THE PARTY RULES. August 2 (15). From THE LETTER TO Y. D. STASOVA, F. V. LENGNIK, AND OTHERS, October 10 14, l904 From SOCIAL-DEMOCRACY AND THE PROVISIONAL REVOLUTIONARY 11 GOVERNMENT FIFTH CONGRESS OF THE RSDLP, April 30-May 19 (May 13—June 1), 1907 13 From SPEECH ON THE REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE DUMA GROUP From THE AIM OF THE PROLETARIAN STRUGGLE IN OUR REVOLUTION TO G. -

Spartacist No. 43-44 Summer 1989

NUMBER 43-44 ENGLISH EDITION . "Market Socialism" Breeds More Misery " in the USSRI . SEE PAGE 5 . When Was the Soviet Thermidor? Kor,qa npoM30wen cOBeTcKM~ TepMMAop? AUSTRALIA .... A $2 BRITAIN .... £1 CA!IIADA .... C$1.75 USA .... US$1.50 2 SPARTACIST. Table of Contents Letters Some Political Bandits at the End ......... 2 Some Political. Luxemburg and Lenin and Liebknecht .... 3 I "Market Socialism" Breeds More Misery Bandits at the End For Workers Political Revolution 22nd March 1988 in the USSR!. ................... ~ .............. 5 Dear Comrade, Special English-Russian Section . Obviously, it is impor;ant that we gain the maximu~ , When Was the Soviet Thermidor? ........ 16 support for the campaign to get the Russian government to release- all documents relating to Leon Trotsky and the KorAa npOM30wen COBeTCKMM TepMMAop?. 17 Moscow trials. Truth must out. The trail of blood left by Stalinism needs to be acknowledged by all, even if it is I The Fight for COmmunist Leadership . unpalatable to some communists. International Communist League By the 'same token, we must see that errors of a similar, Launched .;.'.................................. 18 type are not committed in this country by people purport ing to be Trotskyists. That is why the current issue of the Adapted from Workers Vanguard No. 479, 9 June 1989 Syndicalist journal, Solidarity, is so alarming. It contains a secret internal report of the WRP. , Organizational Appendix to This shows that the WRP received large infusions of "Declaration for the Organizing of funds from Libya and other Middle East governments. an International Trotskyist Tendency" Apparently, a total of at least £ I ,075, 163 came from these sources.