Towards Empowerment ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results for H1 FY14

Financials 3 - 22 About Balaji Telefilms 23 - 24 Television 25 - 27 Motion Pictures 28 - 33 Business Outlook FY2014 34 - 35 2 3 Q2 & H1 FY14 (Standalone) Results for Q2 FY14 • Revenues stood at ` 29,84 lacs {` 34,83 lacs in Q2 FY13} • EBITDA is at (` 65) lacs {` 73 lacs in Q2 FY13} • PAT is at ` 80 lacs {(` 1,16) lacs in Q2 FY13} Results for H1 FY14 • Revenues stood at ` 51,79 lacs {` 70,76 lacs in H1 FY13} • EBITDA is at (` 1,92) lacs {` 3,30 lacs in H1 FY13} • PAT is at ` 8,23 lacs {` 3,22 lacs in H1 FY13} • Diluted EPS not annualised was at ` 1.26 per share {` 0.49 in H1 FY13} Contd…. 4 Q2 & H1 FY14 (Standalone) Contd… • Lower margin owing to launch of two new shows which takes at least a quarter to stabilise: o Jodha Akbar a first time ever costume drama has achieved No.1 position on Zee TV and No.2 across GECs o Pavitra Bandhan was launched on Doordarshan • Hours for Hindi Commissioned programs stood at 121 hours • Average realisation per hour was at ` 24.66 lacs {` 17.61 lacs in Q2 FY13} • EBITDA loss of ` 65 lacs as against profit of ` 73 lacs in Q2 FY13 – due to drop in revenues • Other overheads costs continues to be lower as a result of strict cost controls • PAT grew by 169% to ` 80 lacs mainly due to other income as compared to Q2 FY13 5 Shows Channel Time Schedule Position Monday to No.1 Fiction show Bade Achhe Lagte Hain Sony TV 22.30-23.00 Thursday of the Channel First time ever Monday to Jodha Akbar (June 18, 2013 Launch) Zee TV 20.00-20.30 costume drama, Friday No. -

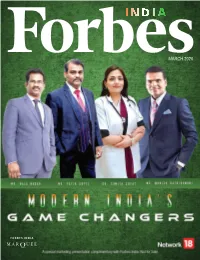

March 2020 from the Editor

MARCH 2020 FROM THE EDITOR: A visionary leader or a company that has contributed to or had a notable impact on the society is known as a game changer. India is a land of such game changers where a few modern Indians have had a major impact on India's development through their actions. These modern Indians have been behind creating a major impact on the nation's growth story. The ones, who make things happen, prove their mettle in current time and space and are highly SHILPA GUPTA skilled to face the adversities, are the true leaders. DIRECTOR, WBR Corp These Modern India's Game Changers and leaders have proactively contributed to their respective industries and society at large. While these game changers are creating new paradigms and opportunities for the growth of the nation, they often face a plethora of challenges like lack To read this issue online, visit: of funds and skilled resources, ineffective strategies, non- globalindianleadersandbrands.com acceptance, and so on. WBR Corp Locations Despite these challenges these leaders have moved beyond traditional models to find innovative solutions to UK solve the issues faced by them. Undoubtedly these Indian WBR CORP UK LIMITED 3rd Floor 207 Regent Street, maestros have touched the lives of millions of people London, Greater London, and have been forever keen on exploring beyond what United Kingdom, is possible and expected. These leaders understand and W1B 3HH address the unstated needs of the nation making them +44 - 7440 593451 the ultimate Modern India's Game Changers. They create better, faster and economical ways to do things and do INDIA them more effectively and this issue is a tribute to all the WBR CORP INDIA D142A Second Floor, contributors to the success of our great nation. -

About Balaji Telefilms

Private and Confidential Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Investor Presentation Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Disclaimer Certain words and statements in this communication concerning Balaji Telefilms Limited (“the Company”) and its prospects, and other statements relating to the Company‟s expected financial position, business strategy, the future development of the Company‟s operations and the general economy in India & global markets, are forward looking statements. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, which may cause actual results, performance or achievements of the Company, or industry results, to differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements are based on numerous assumptions regarding the Company‟s present and future business strategies and the environment in which the Company will operate in the future. The important factors that could cause actual results, performance or achievements to differ materially from such forward-looking statements include, among others, changes in government policies or regulations of India and, in particular, changes relating to the administration of the Company‟s industry, and changes in general economic, business and credit conditions in India. The information contained in this presentation is only current as of its date and has not been independently verified. No express or implied representation or warranty is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the accuracy, fairness or completeness of the information presented or contained in this presentation. None of the Company or any of its affiliates, advisers or representatives accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from any information presented or contained in this presentation. -

“That's Not Real India”

Article Journal of Communication Inquiry 0(0) 1–29 “That’s Not Real India”: ! The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Responses to Women’s DOI: 10.1177/0196859916638648 Portrayals in Indian jci.sagepub.com Soap Operas Indira S. Somani1 and Marissa J. Doshi2 Abstract This study examined the portrayal of women on Indian soap operas through content analysis. Quotes from in-depth interviews of 100 Asian Indians (50 couples) from five major metropolitan areas, NY, DC, SF, Chicago, and Houston, who watch Indian television (imported from India) via the satellite dish or cable, were used in this study. Researchers uncovered specific themes, such as Portrayal of women, Heterosexual Romance and Intimacy, and Joint Family, and analyzed these themes against the theoretical framework of cultural proximity. The authors explained that the role of Indian women being created in Indian serials did not reflect the image of Indian women the participants remembered when they migrated to the United States in the 1960s. The image of Indian women that was being portrayed was that of a “vamp” or someone manipulative and not family-oriented. Therefore, the cultural proximity of the Indian soap operas was disrupted by the negative portrayal of Indian women to a particular generation of Indian immigrants in the United States. The participants appreciated the image of a modern Indian woman, as long as she still maintained traditional values. Further, these portrayals reminded these participants that they were cultural outsiders in modern India. Keywords critical and cultural studies, diasporic identity, gender and media, qualitative research methods, satellite television 1Howard University, Washington, DC, USA 2Hope College, Holland, MI, USA Corresponding Author: Indira S. -

Automatically Generated PDF from Existing Images

Investor Presentation Q3 & 9M FY2015 Disclaimer Certain statements in this document may be forward-looking statements. Such forward- looking statements are subject to certain risks and uncertainties like government actions, local political or economic developments, technological risks, and many other factors that could cause its actual results to differ materially from those contemplated by the relevant forward-looking statements. Balaji Telefilms Limited (BTL) will not be in any way responsible for any action taken based on such statements and undertakes no obligation to publicly update these forward-looking statements to reflect subsequent events or circumstances. The content mentioned in the report are not to be used or re- produced anywhere without prior permission of BTL. 2 Table of Contents Financials 4 - 19 About Balaji Telefilms 20 - 21 Television 22 - 24 Motion Picture 25 - 29 3 Performance Overview – Q3 & 9M FY15 Financial & Operating Highlights Q3 & 9M FY15 (Standalone) Results for Q3 FY15 • Revenues stood at ` 57,27 lacs {` 37,80 lacs in Q3 FY14} • EBITDA is at ` 4,25 lacs {` 2,01 lacs in Q3 FY14} • Depreciation higher by ` 45,44 lacs due to revised schedule II • PAT is at ` 3,09 lacs {` 1,66 lacs in Q3 FY14} Contd…. 5 Financial & Operating Highlights Q3 & 9M FY15 (Standalone) Results for 9M FY15 • Revenues stood at ` 146,25 lacs {` 89,59 lacs in 9M FY14} • The Company has investments in Optically Convertible Debentures (OCD’s) in two Private Limited Companies aggregating ` 4,65.81 lacs. These investments are strategic and non-current (long-term) in nature. However, considering the current financial position of the respective investee companies, the Company, out of abundant caution, has, during the quarter provided for these investments considering the diminution in their respective values. -

DEFINATION the Capacity and Willingness to Develop, Organize

DEFINATION The capacity and willingness to develop, organize and manage a business venture along with any of its risks in order to make a profit. The most obvious example of entrepreneurship is the starting of new businesses. In economics, entrepreneurship combined with land, labor, natural resources and capital can produce profit. Entrepreneurial spirit is characterized by innovation and risk-taking, and is an essential part of a nation's ability to succeed in an ever changing and increasingly competitive global marketplace. Differences Between Women and Men Entrepreneurs When men and women start companies, do they approach the process the same way? Are there key differences? And how do those differences affect the success of the business venture? As a woman in the start-up community, I am frequently asked about women entrepreneurs. A popular question is: How are they different from men? There have been many studies of entrepreneurs and start-ups, and I’ve read a number of them. Many of them seem to me to fall short, because the researchers, not being entrepreneurs themselves, lack an in-depth understanding of the entrepreneurial mind. The result is often a lot of statistics that fail to enlighten readers about entrepreneurial behavior and motivation. So what follows are my personal opinions. They are not based on formal research, but on my own observations and interactions with other women entrepreneurs. 1. Women tend to be natural multitaskers, which can be a great advantage in start-ups. While founders typically have one core skill, they also need to be involved in many different aspects of their business. -

Economic Growth Recorded in FY2015, Buoyed by Improved Agricultural Performance and Growth in Consumption

Management Discussion & Analysis FY2015-16 The Indian economy remained resilient and grew by 7.6% in FY2016, making it the world’s fastest growing economy among the large economies. This was higher than 7.2% economic growth recorded in FY2015, buoyed by improved agricultural performance and growth in consumption. Economic OVERVIEW GLOBAL ECONOMY Calendar Year 2015 (CY2015) has been challenging and difficult year for the global economy. Global growth is said to pick up after a number of weak years (global economic activity remained subdued in CY2015). Global growth, estimated at 3.1% in CY2015, is projected to improve to 3.4% in CY2016 and 3.7% in CY2017. The pick-up in global activity is projected to be more gradual, especially in the emerging markets and the developing economies. In its semi-annual World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) stated that the world economy is facing the threat of a synchronised slowdown and mounting risks including another bout of financial market turmoil, and a political backlash against globalisation. Worldwide, demand remained weak and the recent volatility in financial markets highlighted an uncertain international outlook, especially in China. “The emerging economies are slowing down, apart from India which is “doing pretty well”, Christine Lagarde, the chief of the International Monetary Fund stated. The pace of global GDP growth remained slow, driven by a collusion of multiple factors such as volatility and rebalancing in the Chinese economy. A drop in oil and other commodity prices, slowdown in emerging economies, and slow pick-up in major developed economies also contributed to the slow growth. -

Page 1 CMYK DAILY CROSSWORD DD I 0830 Health Laws of India

DLD‰†‰KDLD‰†‰DLD‰†‰MDLD‰†‰C DELHI TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA, TUESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2003 DAILY CROSSWORD DENNIS THE MENACE HEALTH CAPSULE GRAFFITI BELIEVE IT OR NOT TELEVISION tvguide.indiatimes.com CINEMA DD I Lava & Rockets Challenge 03 Issue of the Day ENGLISH FILMS HINDI FILMS BOL TARA BOL 1100 Rollerjam (Season II) 1400 Sailing: The Moet Cup ZEE NEWS 0830 Health Laws of India 1200 Pacific Blue (Season 1500 Golf Programming 03 Anahat (A) (Marathi with Eng. Subtitles): (Amol Palekar, Wah Wah Ramji : (Amar Upadhyaya, Reema Sen, Gul- Shelly von Strunckel 0900 Naina 0900-1230 Bulletin- Every Sonali Bendre) PVR Saket (12.45 & 9.05 p.m.); Bullet- shan Grover) Delite, M2K (1, 3.40, 6.15 & 10.40 p.m.), V): Kidnapped 1730 Rugby World Cup 0930 North East Prog. Half An Hour proof Monk (A): (Chow Yun-Fat, M4U (S’bad) (12.45, 3.45, 6.45 & 9.45 p.m.), PVR Gur- 1300 Ripley’s Believe 1830 Tennis Masters Cup ARIES (March 21 - April 19) Making promises is one 1000 News in Sanskrit 0830 News Top 10 Seann William Scott) DT Cinemas gaon (1.50, 4.40, 7.40 & 10.30 p.m.), PVR Naraina (11.05 It or Not Houton 03 thing, keeping them quite another.You’re on the verge 1005 Sanad Rahe 1300 Beyond Headlines (12 noon & 6.15 p.m.), M2K (11 a.m., 4.40 & 10.15 p.m.), PVR Saket (3.40 & 8.30 p.m.), 1600 Rescue 911 1930 Sportsline Hindi LIVE of making a commitment that could prove unexpect- 1030 ETV Prog. -

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number 80130 Keshav Uttar Pradesh muzaffarnag Muzaffarnagar Vill Tejalhera, 251307 Trainee Associate Vidhan Singhal [email protected] 9837140332 Polytechnic ar Barla-Basra Road 85950 CH.SANT RAM Haryana karnal Karnal CH.SANT RAM 132041 Trainee Associate SURENDER [email protected] 9416393201 MEMORIAL SR. SEC. SCHOOL KUMAR PUBLIC SR.SEC SCHOOL 86568 Mantra Swami Rajasthan Nohar Hanumangarh Ward no 7 , Near 335523 Trainee Associate Abhishek Solanki [email protected] 9694415086 Vivekanand Skill laxmi ice factory Development Institut 86554 Bigus Skills West Bengal Katiahat North 24 P.O. Katiahat, 743427 Cashier,Trainee Prasun Kanti [email protected] 9851189400 Katiahat Parganas Baduria Basirhat Associate,Sales Biswas road, Dist. 24Prg Associate,Distribu (N), west Bengal tor Salesman 86518 Training Centre Jharkhand karon Deoghar Kusum Bhavan 815357 Store Ops Rakesh Kumar [email protected] 9934379311 Assistant,Cashier, Singh Trainee Associate 84823 Training Center Bihar purnia Purnea Vill- Sukshena, 854203 Store Ops Jitendra Kumar [email protected] 9771232721 Po- Bhatuter Assistant,Sales Mishra chakla, Dist- Associate Purnea 86015 GAYTRI SR.SEC. Haryana karnal Karnal gaytri 132054 Trainee Associate Brij bhushan [email protected] 9466067100 SCHOOL sr.sec.school 85951 AMAR JYOTI Haryana karnal Karnal amar jyoti 132054 Trainee Associate parveen kumar [email protected] 9813136213 SR.SEC.SCHOOL sr.sec.school 82249 Banyan Rajasthan jaipur Jaipur 1&1a, dev nagar, 302015 Trainee Associate Ravi shanker [email protected] 1412711924 edulearning opp. kamal and chouhan solution pvt.ltd. company, gopalpura bypass jaipur 84426 triveni kendra Uttar Pradesh firozabad Firozabad vill. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

“BEING INSTITUTIONAL” Pg

Spine to be adjusted by printer ANNUAL REPORT 2014 -15 TELEVISION Developing Strong Brand Equity Pg. 42 Collaborating Creatively Pg. 44 “BEING world.com INSTITUTIONAL” Pg. 16 Ekta Kapoor dickenson MOVIES www. Optimising Pg. 52 dickenson Creative Strengths Creating an Exciting Pipeline Pg. 54 C-13, Balaji House, IPR Dalia Industrial Estate, Opposite Laxmi Industrial Estate, New Link Road, Andheri (West) Mumbai - 400 053. Monetising Current Assets Pg. 38 www.balajitelefilms.com Adding New Properties Pg. 39 Spine to be adjusted by printer Spine to be adjusted by printer 9 6 8 10 2 5 7 1 4 1. Ms. Ekta Kapoor 2. Mr. Sameer Nair The ‘Balaji’ brand is getting bigger each day. 3. Ms. Tanusri Dasgupta 4. Mr. Shubhodip Pal We have a strong visibility of our TV and movies 5. Mr. Ketan Gupta slate for 2016 and 2017 which underpins a 6. Mr. Tushar Hiranandani positive outlook. Our key drivers in FY2016 will 7. Ms. Coralie Ansari be great ideas, packaging and marketing. We 8. Mrs. Simmi Singh Bisht 9. Mr. Tanveer Bookwala will continue to focus on building strong brand 10. Ms. Ruchikaa Kapoor franchises to better connect with our TV and 11. Mr. Sanjay Dwivedi 3 film audiences. 12. Mr. Vimal Doshi 13. Mr. Ayan Roy Chowdhury Spine to be adjusted by printer 13 12 11 A transformational change is currently underway at the Balaji House. As a promoter driven company, Balaji has travelled a great journey of growth, stature and maturity. Thanks to the love, passion and hard work of the Kapoor family, Balaji now stands at the forefront of the entertainment industry and has the opportunity to travel into new orbits of growth. -

Quarterly Performance Review – Q3 FY17 and 9M FY17

Quarterly Performance Review – Q3 FY17 and 9M FY17 Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Contents 1 About Balaji Telefilms 2 Performance review for Q3 FY17 and 9M FY17 3 Financials 2 Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive About Balaji Telefilms A leading entertainment Owning 19 modern house in India studios and 31 editing since 1994 suites - more than any Indian company in Media Moved towards Entertainment Sector Demonstrated ability to create high quality content Executed over 17,000+ hours of television content in Strong presence in Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Hindi General Kannada, Malayalam Entertainment and Bengali Channels (GECs) entertainment across and Regional GECs genres across India 4 Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Successful storytellers across formats and audiences TV Digital Movies Television programming has been the foundation Subscription based video stone streaming platform Combination of modest budget, high-concept movies as well as high- Unmatched track record Premium, Original and profile big star-cast films with string of hit shows – Exclusive content Hindi and Regional Balance of creativity and Allow users to watch profitability Proven ability in gauging high quality content the pulse of masses – across multiple current shows continue connected devices Emphasis on film content to garner strong TRP rather then the star cast 10 Primetime shows on air across leading GECs and National Television 5 Unique, Distinctive, Disruptive Our strategy is to be where our audience is… Films Television BE SELECTIVE with