A Witch Bottle from the Judges Lodging, York, and Its 16Th and 17Th Century Context By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explored Countless Lab- Oratories, Interviewed a Myriad of Scientists, and Prepared Thousands of News Releases, Feature Articles, Web Sites, and Multimedia Packages

Explaining Research This page intentionally left blank Explaining Research How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work Dennis Meredith 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Dennis Meredith Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meredith, Dennis. Explaining research : how to reach key audiences to advance your work / Dennis Meredith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-973205-0 (pbk.) 1. Communication in science. 2. Research. I. Title. Q223.M399 2010 507.2–dc22 2009031328 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my mother, Mary Gurvis Meredith. She gave me the words. This page intentionally left blank You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother. -

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan FINAL DRAFT Simpson & Brown Architects With Addyman Archaeology August 2012 Contents Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 11 2.1 Objectives of the Conservation Plan ...............................................................................11 2.2 Study Area ..........................................................................................................................11 2.3 Heritage Designations.......................................................................................................13 2.4 Structure of the Report......................................................................................................14 2.5 Adoption & Review...........................................................................................................15 2.6 Other Studies......................................................................................................................15 2.7 Limitations..........................................................................................................................15 2.8 Orientation..........................................................................................................................15 2.9 Project Team .......................................................................................................................15 2.10 Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................16 2.11 Abbreviations and Definitions.........................................................................................16 -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g. -

St Nicks Environment Centre, Rawdon Avenue, York YO10 3FW 01904 411821 | [email protected] |

The list below shows the properties we collect from. Depending on access some properties may have a different collection day to the one shown below. Please contact us to check. Please contact us on the details shown at the bottom of each page. This list was last updated JULY 2021. 202120201 ALDWARK TUE BAILE HILL TERRACE THUR BARLEYCORN YARD FRI BARTLE GARTH TUE BEDERN TUE BISHOPHILL JUNIOR MON BISHOPHILL SENIOR THUR BISHOPS COURT THUR BLAKE MEWS WED BLAKE STREET WED BLOSSOM STREET MON BOLLANS COURT TUE BOOTHAM WED BOOTHAM PLACE WED BOOTHAM ROW WED BOOTHAM SQUARE WED BRIDGE STREET MON BUCKINGHAM STREET THUR BUCKINGHAM COURT THUR BUCKINGHAM TERRACE THUR CASTLEGATE WED CATHERINE COURT WED CHAPEL ROW FRI CHAPTER HOUSE STREET TUE CHURCH LANE MON CHURCH STREET WED CLAREMONT TERRACE WED CLIFFORD STREET WED COFFEE YARD WED COLLEGE STREET TUE COLLIERGATE WED COPPERGATE WED COPPERGATE WALK WED CRAMBECK COURT MON CROMWELL HOUSE THUR CROMWELL ROAD THUR DEANGATE FRI DENNIS STREET FRI St Nicks Environment Centre, Rawdon Avenue, York YO10 3FW 01904 411821 | [email protected] | www.stnicks.org.uk Charity registered as ‘Friends of St Nicholas Fields’ no. 1153739. DEWSBURY COTTAGES MON DEWSBURY COURT MON DEWSBURY TERRACE MON DIXONS YARD FRI FAIRFAX STREET THUR FALKLAND STREET THUR FEASEGATE WED FETTER LANE MON FIRE HOUSE WED FIRE APARTMENTS WED FOSSGATE FRI FRANKLINS YARD FRI FRIARGATE WED FRIARS TERRACE WED GEORGE HUDSON STREET WED GEORGE STREET FRI GILLYGATE WED GLOUCESTER HOUSE WED GOODRAMGATE TUE GRANARY COURT TUE GRANVILLE TERRACE WED GRAPE -

Architecture and Meaning in the Structure of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK Timothy Darvill

Houses of the Holy: architecture and meaning in the structure of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK Timothy Darvill Timothy Darvill is Professor of Archaeology in the Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Forensic Science, Bournemouth University, UK. His research interests lie in the Neolithic of Northwest Europe and in archaeological resource management, and he has carried out fieldwork in Germany, Russia, Malta, England, Wales, and the Isle of Man. In 2008, together with Geoff Wainwright, he undertook excavations inside the stone circles at Stonehenge as part of ongoing research into the links between Stonehenge and the sources of the Bluestones in the Preseli Hills of southwest Wales. He is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Time & Mind. [email protected]. Abstract Stonehenge in central southern England is internationally known. Recent re-evaluations of its date and construction sequence provides an opportunity to review the meaning and purpose of key structural components. Here it is argued that the central stone structures did not have a single purpose but rather embody a series of symbolic representations. During the early third millennium this included a square-in- circle motif representing a sacred house or ‘big house’ edged by the five Sarsen Trilithons. During the late third millennium BC, as house styles changed, some of the stones were re-arranged to form a central oval setting that perpetuated the idea of the a sacred dwelling. The Sarsen Circle may have embodied a time- reckoning system based on the lunar month. From about 2500 BC more than 80 bluestones were brought to the site from sources in the Preseli Hills of west Wales about 220km distant. -

Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande PDF Book

WITCHCRAFT, ORACLES AND MAGIC AMONG THE AZANDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, Eva Gillies | 304 pages | 24 Jun 1976 | Oxford University Press | 9780198740292 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande PDF Book Apr 26, Hayley rated it it was ok. It is very detailed and Pritchard shares everything he knows about the Azande practices. Paradox though it be, the errors as well as valid judgments of the oracle prove to them its infallibility. Therefore the Azande believe people to be fully aware and responsible of their actions at all times. As a descendant of the zande tribe, how can I find detailed different clans in zande tribe and the respect patterns between the Azande people? The witchcraft, apparently, is reasonably benign, and one may be a witch without knowing it. What's Your Deadline? Author: admin. Another type of movie magic , is a director's ability to bring written words to life. Wow, what an amazing book. Sign Up and See Pricing. Primarily though the focus is on the poison oracle, the findings of which are regarded as undeniable fact and primary source of court justification before British rule. Thank you Sir Ghio Reyes, Mrs. It is not blind faith but one which conforms to human behavior, understanding, and rational thought. Evans-Pritchard studied the Azande and their beliefs and ideas of Witchcraft among this culture. Sort order. Throughout the book, Evans-Pritchard exhibited he had no set opinion of whether he believes in the Azande witches or not. These beliefs, although only one aspect of their society, are so prevalent in every-day life that the book is able to detail the important parts of Azande life and death through the study of them. -

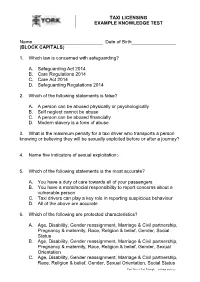

TAXI LICENSING EXAMPLE KNOWLEDGE TEST Name___Date of Birth

TAXI LICENSING EXAMPLE KNOWLEDGE TEST Name___________________________ Date of Birth_________________ (BLOCK CAPITALS) 1. Which law is concerned with safeguarding? A. Safeguarding Act 2014 B. Care Regulations 2014 C. Care Act 2014 D. Safeguarding Regulations 2014 2. Which of the following statements is false? A. A person can be abused physically or psychologically B. Self neglect cannot be abuse C. A person can be abused financially D. Modern slavery is a form of abuse 3. What is the maximum penalty for a taxi driver who transports a person knowing or believing they will be sexually exploited before or after a journey? 4. Name five indicators of sexual exploitation:- 5. Which of the following statements is the most accurate? A. You have a duty of care towards all of your passengers B. You have a moral/social responsibility to report concerns about a vulnerable person C. Taxi drivers can play a key role in reporting suspicious behaviour D. All of the above are accurate 6. Which of the following are protected characteristics? A. Age, Disability, Gender reassignment, Marriage & Civil partnership, Pregnancy & maternity, Race, Religion & belief, Gender, Social Status B. Age, Disability, Gender reassignment, Marriage & Civil partnership, Pregnancy & maternity, Race, Religion & belief, Gender, Sexual Orientation C. Age, Disability, Gender reassignment, Marriage & Civil partnership, Race, Religion & belief, Gender, Sexual Orientation, Social Status Taxi Driver Test Example – without answers D. Age, Disability, Hair colour, Marriage & Civil partnership, Pregnancy & maternity, Race, Religion & belief, Gender, Sexual Orientation 7. In which of the following situations are you protected from discrimination? A. At work B. As a consumer C. When using public services, including taxis D. -

1 the Material Culture of Post-Medieval Domestic Magic In

Accepted Manuscript. Book chapter (https://doi.org/10.30965/9783846757253_017) published in The Materiality of Magic (https://doi.org/10.30965/9783846757253), Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 10 May 2019. The Material Culture of Post-Medieval Domestic Magic in Europe: Evidence, Comparisons, and Interpretations Owen Davies1 In his retirement the Deputy Director of the Museum of London and specialist on Roman London, Ralph Merrifield (1913-1995), wrote a book entitled The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic (1987) that drew upon his note-making during some forty years in the museums services of south-eastern England. With his interest in folklore and religion, Merrifield was curious about odd finds found in odd locations, from sites dating from the Roman period through to the twentieth century, which were ignored by academic archaeologists and were a puzzle to the museums that received them. Shoes buried in walls, animal bones under hearthstones, bent coins and tokens found on the Thames foreshore, chickens found in wall cavities. Was it all rubbish? Did these stray finds have any meaning? Merrifield had eclectic interests and by his retirement he had accumulated a large file of miscellaneous information. “Getting this into order not only revealed new complexities and some unexpected relationships, together with a number of curious survivals,” he explained, “but also made it necessary to reconsider the theoretical basis of interpretation.”2 The unexpected relationships were revealed by Merrifield’s comparison of artefacts and deposition behaviour across two millennia, an approach that was highly original for the time – and remains so today. He was also in the early vanguard of archaeologists interested in the “archaeology of the mind” or cognitive archaeology, and in particular the study of pervasive ritual in prehistory and early history, interests he noted that potentially marked one out as within the “loony fringe” of archaeology at the time. -

York, 6 Blake Street

TO LET CITY CENTRE RETAIL UNIT GROUND FLOOR 146 SQ M (1,573 SQ FT) 6 BLAKE STREET YORK YO1 8QG 46 Bootham York YO30 7BZ Tel 01904 622226 www.wcsyork.co.uk Email [email protected] LOCATION The premises are situated on the western side of Blake Street, one ofHeader the main pedestrian routes into York city centre. Description Blake Street links Museum Street and Duncombe Place junction with St Helens Square. As such, the premises are situated within a popular retailing area and would be suitable for a wide range of retailers. Notable multiple retailers in the area include McD onalds, Toni & Guy, New Look, Lakeland Clothing, Crabtree & Evelyn and Betty’s Tearooms. DESCRIPTION The premises comprise a ground floor retail unit with additional basement storage. A communal passageway to the side of the premises provides access to the rear and refuse storage. The premises provide the following approximate dimensions and SERVICES net floor areas:- We understand mains electricity, water and drainage are connected to the premises. Shop frontage 4.45m 14 ft 7 in TERMS Shop depth (to stairs) 12.1m 39 ft 8 in The premises are available to let for a minimum term of 10 years Lower ground floor sales 51.75 sq m 557 sq ft on effective full repairing and insuring terms, subject to an upward only open market rent review at the end of each fifth year. Upper ground floor 94.40 sq m 1,016 sq ft (Kitchen/WCs) RENTAL Basement storage 28.33 sq m 305 Sq ft £37,500 per annum exclusive. -

Facts and Figures

DIG – FACTS AND FIGURES In 1975, St Saviour’s Church was acquired by York Archaeological Trust for storage of finds. In 1990, York Archaeological Trust set up the Archaeological Resource Centre (ARC) DIG opened its doors for the first time on 25th March 2006. Funded by the Millennium Lottery Commission, DIG is a £1 million development that combines an exciting visitor experience with an innovative corporate event offer. DIG was awarded the ‘York Tourism Attraction of the Year’ at the York Tourism Awards on 10th November 2006. The four dig pits are based on four iconic excavations undertaken by the Trust in recent times: the Roman fortress at Blake Street, the Viking settlement of Jorvik at Coppergate, the medieval priory at Fishergate, the Victorian slum dwellings at Hungate, York. DIG includes workshops, demonstrations, and presentations that can be tailor-made to the audience's ability. School group activities cater for pupils from key stages 1 to 4 with cross-curricular links in history and science plus key elements of English, maths, geography, citizenship and art and design. York Archaeological Trust owns the centre and is an independent educational charity based in York [Registered charity in England & Wales (No. 509060) and Scotland (No. SCO42846)]. ATTRACTION WALK-THROUGH Visitors to DIG will be able to take part in a simulated excavation, discover ‘real’ artefacts from York’s history and also understand how archaeologists recreate the past. The intrepid explorers will start their experience in the briefing room where they will get the inside track on digging for archaeological finds and be kitted out with a trowel, one of the essential tools of the archaeology trade. -

YBAC Stores Not to Be Entered by Excluded Persons 211117

Member stores as of 131217 Store Street Town Postcode Boots the Chemist (Alliance) The Old School York YO24 3BN Boots the Chemist Coney Street York YO1 9QL Cooperative Beckfield Lane York YO26 5EN Cooperative Regent Buildings York YO26 4LT Cooperative Beagle Ridge Drive York YO24 3JQ Dean's Garden Centre Stockton Lane York YO32 9KE Debenhams Davygate York YO1 8RJ Fenwick Ltd St Mary's Square York YO1 9WY JD Sports Fashion 668 Coney Street York YO1 9QL Jojo Maman Bebe Low Petergate York YO1 7HY Lakeland High Ousegate York YO1 8RZ Marks and Spencer Pavement York YO1 8NB McDonalds Blake Street York YO1 8QG Monks Cross Shopping Park Trust Monks Cross Drive York YO32 9GX Museum Gardens, York Museums Trust St Mary's Lodge York YO30 7DR Poundland York Low Petergate York YO1 7HZ Shared Earth Minster Gates York YO1 7HL Sportsdirect Davygate York YO1 8DR Superdrug Market Street York YO1 8SL Tesco Express Low Ousegate York YO1 9QX The Disney Store Parliament Street York YO1 2SG The Little Diamond Shop Lendal York YO1 8AQ TopShop/Topman St. Mary's Square York YO1 9NT Vision Express Parliament Street York YO1 8SE Gap Inc Davygate York YO1 8RJ W H Smith Coney Street York YO1 9QL Mulberry Company Ltd Swinegate York YO1 8AZ Boots the Chemist St Mary's Square York YO1 9NY Jack Wills Stonegate York YO1 8AS Mango Coney Street York YO1 9QL Sainsburys Blossom Street York YO24 1AP Tesco Express Goodramgate York YO1 7LS Sainsburys Local Bootham York YO30 7BT Sainsburys Local Micklegate York YO1 6WG Fatface High Ousegate York YO1 8RZ TK Maxx Coney Street York