Turnock Luke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Celebrity Birthday Book!

2 Contents 1 2018 17 1.1 January ............................................... 17 January 1 - Verne Troyer gets the start of a project (2018-01-01 00:02) . 17 January 2 - Jack Hanna gets animal considerations (2018-01-02 09:00) . 18 January 3 - Dan Harmon gets pestered (2018-01-03 09:00) . 18 January 4 - Dave Foley gets an outdoor slumber (2018-01-04 09:00) . 18 January 5 - deadmau5 gets a restructured week (2018-01-05 09:00) . 19 January 6 - Julie Chen gets variations on a dining invitation (2018-01-06 09:00) . 19 January 7 - Katie Couric gets a baristo’s indolence (2018-01-07 09:00) . 20 January 8 - Jenny Lewis gets a young Peter Pan (2018-01-08 09:00) . 20 January 9 - Joan Baez gets Mickey Brennan’d (2018-01-09 09:00) . 20 January 10 - Jemaine Clement gets incremental name dropping (2018-01-10 09:00) . 21 January 11 - Mary J. Blige gets transferable Bop-It skills (2018-01-11 09:00) . 22 January 12 - Raekwon gets world leader factoids (2018-01-12 09:00) . 22 January 13 - Julia Louis-Dreyfus gets a painful hallumination (2018-01-13 09:00) . 22 January 14 - Jason Bateman gets a squirrel’s revenge (2018-01-14 09:00) . 23 January 15 - Charo gets an avian alarm (2018-01-15 09:00) . 24 January 16 – Lin-Manuel Miranda gets an alternate path to a coveted award (2018-01-16 09:00) .................................... 24 January 17 - Joshua Malina gets a Baader-Meinhof’d rice pudding (2018-01-17 09:00) . 25 January 18 - Jason Segel gets a body donation (2018-01-18 09:00) . -

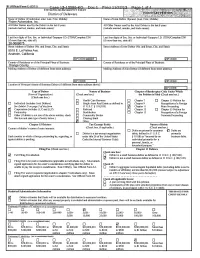

I I I Case 13-13086-KG Doc 1 Filed 11/22/13 Page 1 of 4

B! (Official Form 11 (12/11) Case 13-13086-KG Doc 1 Filed 11/22/13 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT District of Delaware YOLIJ1"4T4RYPET1TION - Name of Debtor (if individual, enter Last, First, Middle): Name of Joint Debtor (Spouse) (Last, First, Middle): Fisker_ Automotive, _Inc. All Other Names used by the Debtor in the last 8 years All Other Names used by the Joint Debtor in the last 8 years (include married, maiden, and trade names): (include married, maiden, and trade names): Last four digits of Soc. Sec. or Individual-Taxpayer I.D. (ITIN)/Complete Eli') Last four digits of Soc. Sec. or individual-Taxpayer I.D. (ITIN)/Complete EIN (if more than one, state all): (if more than one, state all): 26-0689075 Street Address of Debtor (No. and Street, City, and State): Street Address of Joint Debtor (No. and Street, City, and State): 5515 E. La Palma Ave. Anaheim, California IZIP CODE 92807 I VIP CODE I County of Residence or of the Principal Place of Business: County of Residence or of the Principal Place of Business: Orange County Mailing Address of Debtor (if different from street address): Mailing Address of Joint Debtor (if different from street address): IZIP CODE I IZIP CODE I Location of Principal Assets of Business Debtor (if different from street address above): IZIP CODE I Type of Debtor Nature of Business Chapter of Bankruptcy Code Under Which (Form of Organization) (Check one box.) the Petition is Filed (Check one box.) (Check one box.) El Health Care Business D Chapter 7 0 Chapter 15 Petition for 0 Individual (includes Joint Debtors) 0 Single Asset Real Estate as defined in 0 Chapter 9 Recognition of a Foreign See Exhibit Don page 2 of thisform. -

5G Coronavirus Briefing 19 April

5G / Coronavirus Briefing 19 April 2020 CONTENTS (hyperlinks) Newest entries appear at start of each section Some sections may have no entries in this edition Notes from compiler appear in red Medical doctors refuting Coronavirus Action AI / Mind Control The only means to fight the plague is honesty. Analysis Albert Camus, The Plague (1947) Big picture/overview Censorship Comment Conspiracy Control Controlled opposition? 5G rollout Digital currency Disinformation Dissent Essential reading 5G / Coronavirus health aspects Hoax Humour News Crimes against humanity Nigel Farage: Resistance https://twitter.com/Nigel_Farage/status/12514566318519 Space 54178 Solutions / inspiration This was the scene in a Romanian airport yesterday as workers headed to Germany. As we know, seasonal Surveillance / Privacy workers from Eastern Europe have already made their Vaccinations way to Britain. As I have said for many weeks — flying Appendix: Coronavirus symptoms people in without a period of quarantine would be disastrous. MEDICAL DOCTORS QUESTIONING CORONAVIRUS (ongoing) Note: Director-General of WHO, Ethiopian Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is the first WHO D-G who is not a medical doctor. He holds an undergraduate degree in biology, a masters degree in immunology of infectious diseases and a PhD in community health. BRUTAL: 5 awful facts about WHO’s Tedros Adhanom: https://www.rebelnews.com/who_director_general_tedros_adhanom_isnt_medical_doctor_ally_chi na_troubling_human_rights_record?utm_campaign=kb_who_director_general&utm_medium=emai l&utm_source=therebel Open letter to the WHO: Purge Dr. Tedros Adhanom out or face the shame!: https://www.ethiopianregistrar.com/open-letter-purge-dr-tedros-adhanom-or-face-shame-muluken- gebeyew/ Videos of doctors - recommended by David Icke: https://www.davidicke.com/article/567397/vital-videos-watching-david-ickes-london-real-interview- today 2 5G / Coronavirus Briefing 19 April 2020 Available at http://toxi.com/5g Ayyadurai Dr. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Suarez, Jorge Ramiro Perez We are Cyborgs: Developing a Theoretical Model for Understanding Criminal Behaviour on the Internet Original Citation Suarez, Jorge Ramiro Perez (2015) We are Cyborgs: Developing a Theoretical Model for Understanding Criminal Behaviour on the Internet. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/28324/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ WE ARE CYBORGS: DEVELOPING A THEORETICAL MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING CRIMINAL BEHAVIOUR ON THE INTERNET JORGE RAMIRO PÉREZ SUÁREZ A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield December 2015 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Residents Fight to Save Neighborhood the El Paso Historical Landmark Commision Suggests the City Reconsiders Arena Location

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP The rP ospector Special Collections Department 11-8-2016 The rP ospector, November 8, 2016 UTEP Student Publications Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/prospector Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Comments: This file is rather large, with many images, so it may take a few minutes to download. Please be patient. Recommended Citation UTEP Student Publications, "The rP ospector, November 8, 2016" (2016). The Prospector. Paper 263. http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/prospector/263 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP ospector by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 102, NO. 12 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO NOVEMBER 8, 2016 Union Plaza residents fight to save neighborhood The El Paso Historical Landmark Commision suggests the city reconsiders arena location MICHAELA ROMÁN / THE PROSPECTOR Flor de Luna Gallery is located at the corner of Chihuahua street and Overland street. It is in the center of the city officials approved arena location. The gallery sits next to the last-standing former brothel in El Paso. BY MICHAELA ROMÁN sion. Commissioners William sy amongst El Pasoans because Sun Metro Transit Authority, ness and residence sits just The Prospector Helm, Edgar Lopez and Don it will displace residents and where author John Peterson outside the arena footprint. Luciano recused themselves business owners in the area. -

Dan Bilzerian Sweepstakes

The Dan Bilzerian Sweepstakes OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN A PRIZE. A PURCHASE WILL NOT IMPROVE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE CONTIGUOUS 48 UNITED STATES AND D.C., 21 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER. VOID IN ALASKA, HAWAII, FLORIDA AND NEW YORK AND WHERE PROHIBITED. EACH WINNER AND (IF APPLICABLE) HIS OR HER GUEST MAY BE REQUIRED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE PRIZE FULFILLMENT PROCESS AND SIGN DOCUMENTATION, SUCH AS A RELEASE, AS MORE FULLY DETAILED BELOW. BY PARTICIPATING, YOU AGREE TO THESE OFFICIAL RULES, WHICH ARE A CONTRACT. WITHOUT LIMITATION, THIS CONTRACT INCLUDES INDEMNITIES TO THE SPONSOR (DEFINED BELOW) FROM YOU AND A LIMITATION OF YOUR RIGHTS AND REMEDIES. THIS SWEEPSTAKES IS VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. 1. How to Enter: Beginning at 10:00 a.m. Pacific Standard Time (“PST”) on April 8, 2015 until 9:00 a.m. PST on April 15, 2015 (the “Sweepstakes Period”), you may enter the “Dan Bilzerian Sweepstakes” (the “Sweepstakes”) by visiting the website (http://party.firstslice.com/ bilzerian-party-contest/) (the “Website”) and completing and submitting the online entry form. Incorrect and incomplete entries are void. FILLING OUT TRIVIA QUESTIONS IS OPTIONAL, IS NOT REQUIRED TO ENTER OR WIN A PRIZE, AND WILL NOT IMPROVE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. These Official Rules are also available on the Website. All entries must be received by the end of the Sweepstakes Period to be valid. There is a limit of one (1) entry, per valid email address, per eligible person, per day. For purposes of this Sweepstakes, a “day” begins at 12:00 a.m. -

Eight Quick Questions / the Players

2015 COLORADO BUFFALO FOOTBALL: Eight Quick Questions / The Players EIGHT QUICK QUESTIONS The players were asked to answer up to eight different questions; here are their responses: Player You can take a Facebook, Ultimate Do you have a How many of How many Create a class Trade places trip anywhere in Twitter, Halloween “can’t miss” the 50 states foreign at CU, what with anyone the world, where Instagram, or Costume? TV show? have you countries have would it be? since start of would it be? Snapchat? visited? you visited? time, who? Michael Adkins Rio De Janeiro Twitter Being Mary Less than half Mexico Money Jane matters Cade Apsay Europe Snapchat How I Met Seven Mexico Your Mother Vincent Arvia Fiji Instagram More than London, Floyd half Ireland, Mayweather Mexico, S. Africa Jaleel Awini Dubai Twitter Old Spice House of Eight Ghana, Analysis of TV Bill Clinton Man Cards / Sons England shows today of Anarchy Chidobe Awuzie Jamaica Snapchat A King Game of 12 Nigeria, Intro to Muhammad Ali Thrones England Confidence JT Bale Normandy beach South Park 15 Lure design George Washington Cameron Spain Twitter Spider Man Key & Peele 13 Germany (born American King Louis XVI Beemster there) history through softball Jered Bell Rio De Janeiro Instagram Power 17 None Wine tasting Michael Jackson or Prince Brian Boatman Italy Instagram Super Sayan The League Less than half Eight Cooking class Rob Gronkowski Bryce Bobo Bora Bora Twitter and Steve Urkel Empire Nine Lunch 101 Denzel Snapchat Washington Chris Bounds Ed Caldwell Jerusalem Myspace Bane from -

5G / Coronavirus Briefing 28 April 2020

5G / Coronavirus Briefing 28 April 2020 CONTENTS (hyperlinks) A single person who stops Newest entries appear at start of each section lying can bring down a Some sections may have no entries in this edition tyranny" Notes from compiler appear in red Alexander Solzenitsyn Medical doctors refuting Coronavirus Action AI / Mind Control Analysis Big picture/overview Censorship Comment Conspiracy Control Crimes against humanity 5G rollout Disinformation Dissent Essential reading 5G / Coronavirus health aspects Hoax Covidiotic News Arthur Firstenberg: Effects of COVID-19 are similar to Programming the public for the NWO effects of radio waves. These [“Covid-19”] symptoms are Resistance all classic symptoms of radio wave sickness. When both Space the virus [Ed.: if you believe in it – I don’t] and RF radiation are present, the disease should be attributed to Solutions / inspiration both: Vaccinations Appendix: Coronavirus symptoms MEDICAL DOCTORS QUESTIONING CORONAVIRUS (ongoing) Note: Director-General of WHO, Ethiopian Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is the first WHO D-G who is not a medical doctor. He holds an undergraduate degree in biology, a masters degree in immunology of infectious diseases and a PhD in community health. Anonymous doctor 21.4.20 - Respiratory doctor blows whistle on fake virus pandemic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVe3PQ-dHwY&feature=youtu.be Any incoming patient is labelled a Covid patient. Most patients were never tested but were recorded as Covid deaths no matter what they died of. They’re showing the numbers like a football game to scare yo. I’ve never seen bodies loaded into a tractor trailer. I really don’t believe that they were bodies. -

Case 13-13087-KG Doc 583 Filed 02/04/14 Page 1 of 227 Case 13-13087-KG Doc 583 Filed 02/04/14 Page 2 of 227 FISKER AUTOMOTIVE HOLDINGS,Case INC

Case 13-13087-KG Doc 583 Filed 02/04/14 Page 1 of 227 Case 13-13087-KG Doc 583 Filed 02/04/14 Page 2 of 227 FISKER AUTOMOTIVE HOLDINGS,Case INC. 13-13087-KG - U.S. Mail Doc 583 Filed 02/04/14 Page 3 of 227 Served 1/28/2014 014 IDS - DELAWARE 2BF GLOBAL INVESTMENTS LTD. 3 DIMENSIONAL SERVICES CHARLOTTE, NC 28258-0027 C/O I2BF LLC 2547 PRODUCT DRIVE ATTN: MICHAEL LOUSTEAU ROCHESTER, MI 48309 110 GREENE ST., SUITE 600 NEW YORK, NY 10012 3 FORM 3336603 CANADA INC. 360 HOLDINGS, LLC 2300 SOUTH 2300 WEST SUITE B ATTN: MICHAEL MIKELBERG C/O ADVANCED LITHIUM POWER SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84119 1455 SHERBROOKE STREET WEST, SUITE 200 SUITE 1308, 1030 WEST GEORGIA STREET MONTREAL, QC H3G 1L2 VANCOUVER, BC V6E 2Y3 CANADA CANADA 3D SCANNING AND CONSULTING 3GC GROUP 3M COMPANY 76 SADDLEBACK ROAD 3435 WILSHIRE BLVD. GENERAL OFFICES / 3M CENTER TUSTIN, CA 92780 LOS ANGELES, CA 90010 SAINT PAUL, MN 55144-1000 8888 INVESTMENTS GMBH 911 RESTORATION A & A PROTECTIVE SERVICES REIDSTRASSE 7 1846 S. GRAND PO BOX 66443 CH-6330 CHAM SANTA ANA, CA 92705 LOS ANGELES, CA 90066 SWITZERLAND A COENS A. BROEKHUIZEN A. FIDDER AC SPECIAL CAR RENTAL AND LEASE BV DE PEEL B.V.B.A. FIDDER BEHEER BV EERSTE STEGGE 1 LEEUWERKSTRAAT 24 HET VALLAAT 26 7631 AE OOTMARSUM B-2360 OUD-TURNHOUT 8614 DC SNEEK NETHERLANDS BELGIUM NETHERLANDS A. POLS A. RAFIMANESH A. VAN VEEN RAADHUISTRAAT 112 A&A CAPACITY ATHLON CAR LEASE NEDERLAND B.V. SPRANG-CAPELLE 5161 BJ BONGERDSTRAAT 5A POSBUS 60250 THE NETHERLANDS 1356 AL MARKERBINNEN 1320 AH ALMERE NETHERLANDS NETHERLANDS A.A. -

Hold the Line for Humanity

5G / Coronavirus Briefing 9 June 2020 HOLD THE LINE FOR HUMANITY CONTENTS (hyperlinks) "Non-cooperation with evil is Newest entries appear at start of each section as much a duty as is Notes from compiler appear in red cooperation with good." ― Mahatma Gandhi Medical doctors refuting Coronavirus Action AI / Mind Control Analysis Big picture/overview Book review Censorship Real eyes realise real lies Comment ― Infinite Waters Conspiracy Corruption “I challenge your answer. Imagine that you are Covidiotic creating a fabric of human destiny with the Crimes against humanity object of making men happy in the end, giving 5G rollout them peace and rest at last, but that it was Depopulation essential and inevitable to torture to death only Disinformation one tiny creature — that baby beating its breast Dissent with its fist, for instance — and to found that Entertainment edifice on its unavenged tears, would you 5G / Coronavirus health aspects consent to be the architect on those conditions? Hoax Tell me, and tell the truth.” News ― Fyodor Dostoyevsky Police state Programming the public for the NWO “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to Resistance be purchased at the price of chains and Space slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know Solutions / inspiration not what course others may take; but as Vaccinations for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Weapon ― Patrick Henry Appendix 1: Facts about Covid-19 Appendix 2: Electrohypersensitivity The men the American people admire Appendix 3: Miscellaneous most extravagantly are the most daring Appendix 4: Companies that support Antifa liars; the men they detest most violently are those who try to tell them the truth. -

2018-19-South-Bay-Lakers-Media

Table of Contents Lakers Staff Playoff Records Team Directory 6 Year-by-Year Results 100 President/CEO Joey Buss 7 Head-to-Head vs. Opponents 100 General Manager Nick Mazzella 7 Career Playoff Leaders 101 Head Coach Coby Karl 8 All-Time Single-Game Highs 102 Assistant Coach Brian Walsh 8 All-Time Highs / Lows 103 Assistant Coach Isaiah Fox 9 Individual Playoff Records (Lakers) 104 Assistant Coach Dane Johnson 9 Opponent All-Time Highs / Lows 105 Assistant Coach Sean Nolen 9 All-Time Playoff Scores 106 Video Coordinator Anthony Beaumont 10 Athletic Trainer Heather Mau 10 Strength & Conditioning Coach Misha Cavaye 10 The Opponents Director, Basketball Operations/Player Development Agua Caliente 108 Nick Lagios 11 Austin 109 Director of Scouting Jesse Buss 11 Canton 110 Capital City 111 Delaware 112 Erie 113 The Players Fort Wayne 114 Individual Player Bios 13-24 Grand Rapids 115 Greensboro 116 The G League Iowa 117 G League Directory 26 Lakeland 118 NBA G League Key Dates 27 Long Island 119 2017-18 Final Standings 28 Maine 120 2017-18 Team Statistics 29-30 Memphis 121 2017-18 Highs / Lows 31 Northern Arizona 122 Champions by Year 32 Oklahoma City 123 NBA G League Award Winners 32 Raptors 124 2018 NBA G League Draft 33 Rio Grande Valley 125 NBA G League Single-Game Bests 34 Salt Lake City 126 Santa Cruz 127 2017-18 Year In Review Sioux Falls 128 Stockton 129 Overall Season Statistics 36 Texas 130 Home / Road Statistics 37 Westchester 131 Lakers Transactions 38 Windy City 132 Breakdown 39 Wisconsin 133 Game-by-Game 40 G League Map 134 Miscellaneous -

First Spiritans Named Cardinals Jinkies!

October 20, 2016 Volume 96 Number 10 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 First Jinkies! At the Greek Carnival DU law Spiritans ranks named No. 2 on cardinals bar exam Raymond Arke Hallie Lauer asst. news editor staff writer Duquesne University law stu- Spiritan priests are a mainstay on dents have once again raised the Duquesne’s campus. Now, for the bar — literally. first time, the order will be repre- As of early October, Duquesne sented in the prestigious College of University law students ranked Cardinals. the second highest on their bar On Oct. 9, Pope Francis an- exam results in Pennsylvania. This nounced the appointment of 17 new is the 10th time in the past 11 years Cardinals during his regular Sunday Duquesne has surpassed the state- address to St. Peter’s Square. Mon- wide average of 75.35 percent, signor Maurice Piat, the Archbishop with 91.96 percent of first-time of Port-Louis, Mauritius, and Monsi- bar exam takers passing. gnor Dieudonné Nzapalainga, Arch- “This is a remarkable showing bishop of Bangui in the Central Afri- by a talented group of law stu- can Republic, have become the first dents and faculty who remained two Spiritas to be named by the pope focused and worked tirelessly as cardinals. to achieve the highest level of Mauritius is a small island nation excellence on the bar exam and off the east coast of Madagascar in succeeded masterfully,” said the Indian Ocean. The Central Afri- Duquesne University President can Republic is located, as the name Ken Gormley, who also was the implies, in the center of the African Jordan Miller/Staff Photographer former dean of the law school.