The U.S. Listing Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stock Exchange Listing Agreements As a Vehicle for Corporate Governance

1981] STOCK EXCHANGE LISTING AGREEMENTS AS A VEHICLE FOR CORPORATE GOVERNANCE INTRODUCTION After nearly two hundred years of operation, stock exchanges remain largely unexplored as vehicles for regulating the internal affairs of corporations whose stocks they list for trading. Such regulation would seek to establish uniform, easily comprehensible standards of corporate conduct and to communicate them to every investor. The standards would be implemented by requiring that corporations conform to them as a prerequisite to having their securities traded on an exchange. As a result, investors could more accurately assess the value of corporate equity securities than they can today, and would be less likely to base an investment decision on a misunderstanding of their potential rights as shareholders.1 In evaluating the price of an equity security today, investors face fifty state corporation laws and as many state judicial systems, which together determine the bundle of rights the investor pur- chases. This problem stems from the principle that state law defines the rights and obligations a corporation owes to its share- holders.2 Investors who have neither the expertise to school them- selves in the nuances of state corporation law nor the resources to hire an attorney for that purpose 3 may choose "safer" invest- ments,4 or equally risky but more understandable investments,5 or I Stock exchanges currently regulate some aspects of internal corporate affairs, see, e.g., note 40 infra, but this Comment advocates greater supervisory powers. Furthermore, because of the relative obscurity of listing agreement provisions, investors do not generally appreciate the specifies of current exchange regulations. -

Why Are the First Day Returns of China's Ipos So High?

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Commerce - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Business and Law 2005 Why Are the First Day Returns of China’s IPOs So High? S. Ma University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers Part of the Business Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Ma, S.: Why Are the First Day Returns of China’s IPOs So High? 2005. https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/474 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Why Are the First Day Returns of China’s IPOs So High? Abstract We investigate the causes of the high first day returns of Chinese firms making an initial public offering (IPO) of A-shares from 1991 to 2003 on Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. Our results show an average underpricing of 175.21 percent. We argue that the IPO underpricing is an interaction of ex-market underpricing and on-market overpricing. The high first day returns of China’s IPOs are most likely generated from on-market overpricing. Government intervention, market speculation, special ownership structure, strategy of proceeds maximization and risk concerns are the main drivers of the high first day returns. However, the high first day returns have decreased significantly in ecentr years. We explained this change by testing the risk composition hypothesis, the realignment of incentives hypothesis and the changing issuer objective hypothesis, which shows that the reduction in risk, senior managerial shares and seasoned offerings mitigate the first day returns. -

Initial Public Offerings

November 2017 Initial Public Offerings An Issuer’s Guide (US Edition) Contents INTRODUCTION 1 What Are the Potential Benefits of Conducting an IPO? 1 What Are the Potential Costs and Other Potential Downsides of Conducting an IPO? 1 Is Your Company Ready for an IPO? 2 GETTING READY 3 Are Changes Needed in the Company’s Capital Structure or Relationships with Its Key Stockholders or Other Related Parties? 3 What Is the Right Corporate Governance Structure for the Company Post-IPO? 5 Are the Company’s Existing Financial Statements Suitable? 6 Are the Company’s Pre-IPO Equity Awards Problematic? 6 How Should Investor Relations Be Handled? 7 Which Securities Exchange to List On? 8 OFFER STRUCTURE 9 Offer Size 9 Primary vs. Secondary Shares 9 Allocation—Institutional vs. Retail 9 KEY DOCUMENTS 11 Registration Statement 11 Form 8-A – Exchange Act Registration Statement 19 Underwriting Agreement 20 Lock-Up Agreements 21 Legal Opinions and Negative Assurance Letters 22 Comfort Letters 22 Engagement Letter with the Underwriters 23 KEY PARTIES 24 Issuer 24 Selling Stockholders 24 Management of the Issuer 24 Auditors 24 Underwriters 24 Legal Advisers 25 Other Parties 25 i Initial Public Offerings THE IPO PROCESS 26 Organizational or “Kick-Off” Meeting 26 The Due Diligence Review 26 Drafting Responsibility and Drafting Sessions 27 Filing with the SEC, FINRA, a Securities Exchange and the State Securities Commissions 27 SEC Review 29 Book-Building and Roadshow 30 Price Determination 30 Allocation and Settlement or Closing 31 Publicity Considerations -

NYSE Listed Company Compliance Guidance Letter

NYSE Regulation 11 Wall Street New York, New York 10005 TO: NYSE Listed Company Executives FROM: NYSE Regulation RE: Listed Company Compliance Guidance for NYSE Issuers DATE: January 14, 2021 Each year, the staff of NYSE Regulation prepares a guidance memo for important rules and policies applicable to companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange (“NYSE” or the “Exchange”). A complete text of Exchange rules can be found online in the NYSE Listed Company Manual (“Listed Company Manual”). We have included items that are new below, with important reminders in the sections that follow. Please note that this memo is applicable to all listed issuers, with any rule or policy differences for Domestic vs. Foreign Private Issuers (“FPIs”) identified within. We encourage you to provide a copy of this memo to appropriate executives and outside advisers who handle matters related to your listing on the NYSE. We have also provided department contact information below. Please do not hesitate to contact the staff with any question or concern you may have. What’s New In response to the market and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NYSE filed with the SEC temporary rules that provided relief to listed companies from certain quantitative and shareholder approval rules in the Listed Company Manual, most of which expired on July 1, 2020. However, the relief pertaining to shareholder approval remains in effect through March 31, 2021. The shareholder approval relief generally waives related party limitations and bona fide private financing requirements in Listed Company Manual Section 312.03 for market price transactions. -

Initial Public Offering Allocations

Initial Public Offering Allocations by Sturla Lyngnes Fjesme A dissertation submitted to BI Norwegian Business School for the degree of PhD PhD specialization: Financial Economics Series of Dissertations 9/2011 BI Norwegian Business School Sturla Lyngnes Fjesme Initial Public Offering Allocations © Sturla Lyngnes Fjesme 2011 Series of Dissertations 9/2011 ISBN: 978-82-8247-029-2 ISSN: 1502-2099 BI Norwegian Business School N-0442 Oslo Phone: +47 4641 0000 www.bi.no Printing: Nordberg Trykk The dissertation may be downloaded or ordered from our website www.bi.no/en/Research/Research-Publications/ Abstract Stock exchanges have rules on the minimum equity level and the minimum number of shareholders that are required to list publicly. Most private companies that want to list publicly must issue equity to be able to meet these minimum requirements. Most companies that list on the Oslo stock exchange (OSE) are restricted to selling shares in an IPO to a large group of dispersed investors or in a negotiated private placement to a small group of specialized investors. Initial equity offerings have high expected returns and this makes them very popular investments. Ritter (2003) and Jenkinson and Jones (2004) argue that there are three views on how shares are allocated in the IPO setting. First, is the academic view based on Benveniste and Spindt (1989). In this view investment banks allocate IPO shares to informed investors in return for true valuation and demand information. Informed investors are allocated shares because they help to price the issue. Second, is the pitchbook view where investment banks allocate shares to institutional investors that are likely to hold shares in the long run. -

The Market Reaction to Cross-Listings: Does the Destination Market Matter?

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Banking & Finance xxx (2009) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Banking & Finance journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbf The market reaction to cross-listings: Does the destination market matter? Peter Roosenboom, Mathijs A. van Dijk * Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, P.O. Box 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, Netherlands article info abstract Article history: This paper examines (i) whether market reactions to cross-listings differ across destination markets and Received 26 November 2008 (ii) to what extent the following explanations for value creation around cross-listings can account for dif- Accepted 17 April 2009 ferences in market reactions across cross-listings on various destination markets: overcoming market Available online xxxx segmentation, increased market liquidity, improved information disclosure, and better investor protec- tion (‘‘bonding”). We analyze 526 cross-listings from 44 different countries on eight major stock JEL classification: exchanges and document significant announcement returns of 1.3% on average for cross-listings on US F30 exchanges, 1.1% on London Stock Exchange, 0.6% on exchanges in continental Europe, and 0.5% (not sig- G14 nificant) on Tokyo Stock Exchange. We find evidence consistent with improved disclosure and bonding G15 creating value for cross-listings on US exchanges, while overcoming segmentation and bonding are asso- Keywords: ciated with higher announcement returns on the London Stock Exchange. The evidence is mixed for con- Cross-listings tinental European exchanges and for Tokyo. Our results highlight the role of the destination market in Capital market integration value creation around cross-listings. Investor protection Ó 2009 Elsevier B.V. -

NYSE Direct Listing Rules Approved; Nasdaq Proposes Substantially Similar Rules

Capital Markets Alert 01 / 06 / 21 NYSE Direct Listing Rules Approved; Nasdaq Proposes Substantially Similar Rules If you have any questions regarding On December 22, 2020, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved the matters discussed in this a proposal by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) that allows companies going memorandum, please contact the public via a direct listing to issue new shares and raise capital without involvement of a attorneys listed on the last page traditional underwriter. The SEC first approved the proposed rules on August 26, 2020, or call your regular Skadden contact. but stayed the approval upon receiving notice that the Council of Institutional Investors intended to petition for review of the rules. After a de novo review, the SEC approved the rules, concluding that the NYSE had “met its burden to show that the proposed rule This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its change is consistent with the Exchange Act.” The NYSE rules, which are immediately affiliates for educational and informational effective, bolster direct listings as a potentially attractive alternative to traditional under- purposes only and is not intended written initial public offerings (IPOs). and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered Nasdaq also recently filed a direct listing rule proposal with the SEC, which would have advertising under applicable state laws. provided for more pricing flexibility than is permitted in the NYSE rules, but the SEC staff delayed approval of the rule, subjecting it to additional procedures for consider- ation. Upon approval of the NYSE rules, Nasdaq filed a substantially similar proposal, One Manhattan West requesting immediate effectiveness. -

NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Checklist for Supporting Documents

NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Checklist for Supporting Documents Required for Original Listing Application This is a checklist for companies that would like to list securities on the NYSE (the “Exchange”). Please note that prior to submitting the following documents to the Exchange, the company will have been cleared to file an original listing application. Documents Required for Authorization to List Draft Original Listing Application Confirmation company meets shareholder requirements Response to clearance letter Letter from the underwriters undertaking that the company will comply with applicable quantitative listing standards (when listing in conjunction with an initial public offering) Listing Agreement executed by an executive officer Depositary Listing Agreement (for foreign private issuers listing American Depositary Receipts) Draft Depositary Agreement (for foreign private issuers listing American Depositary Receipts) Section 315 Letter Draft Form 8-A Copy of charter Copy of bylaws Copy of Board resolutions authorizing: (i) application to list securities on the Exchange; (ii) issuance of any unissued securities (e.g., option plans, shares to be issued upon conversion etc.) for which the listing application is made; and (iii) appointment of the transfer agent/registrar, if any. Copy of shareholder resolutions authorizing issuance (if corporate procedure requires such action) of any unissued securities (e.g., option plans, shares to be issued upon conversion, etc.) for which listing application is made Copy of Specimen -

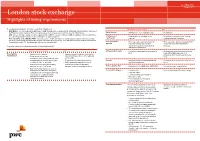

London Stock Exchange Highlightspwc Asset of and Listing Wealth Requirements Management

as of May 2019 Page 1 of 2 London stock exchange HighlightsPwC Asset of and listing Wealth requirements Management The London Stock Exchange offers three markets for listing, they are: Main Market (Premium Listing) AIM • Main Market – it is the London Stock Exchange’s (LSE) flagship market, regulated by the UK Listing Authority (UKLA), a division of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). A company has a choice of segments on which to list on the Main Market. Public flotation • Minimum 25% shares in public hands. • No minimum. • AIM – it is an exchange-regulated market, regulated by the LSE. The market is built on simplified regulatory environment which has been specifically designed for the needs of small and emerging companies. Trading record • Normally three year trading record • No trading record requirement, although requirement • Professional Securities Market (PSM) – it provides a more flexible alternative for raising capital through the listing of specialist required. must be presented if available. securities, including debt and depositary receipts, to professional investors only. The PSM does not require financial information to be presented under IFRS. Instead issuers may use their national GAAP. Prior shareholder • Prior shareholder approval required for • Prior shareholder approval required only for approval significant transactions, including reverse takeovers and fundamental This leaflet highlights the listing requirements for Main Market and AIM. significant acquisitions, disposals and disposals. related party transactions. Main Market (Premium Listing) AIM Admission documents • Pre-vetting of admission documents by the • Admission documents not prevetted by the FCA. London Stock Exchange (unless a Key eligibility • Appointment of a sponsor. • Appointment and retention of a nominated prospectus which would be vetted by the requirements adviser and broker, who must be registered • Production of a prospectus. -

JSE Listing Process JSE Listing Process

Indicative process for admission of a company to the Junior Market Company is incorporated Company appoints advisers: auditor, mentor, broker, attorney Company confirms compliance with tax legislation and financial reporting requirements JSE Listing Process Company drafts prospectus (can be based on business plan) with advisers Company submits prospectus and other shelf All companies must use a broker to list their securities documents to JSE for review at least 21 days before admission on the JSE. Company registers prospectus with Companies Office of Jamaica and FSC For those companies interested in listing securities on Company launches initial public offer with its brokers the US Dollar Equities Market and Bond, kindly refer to the listing process and requirements for the JSE Main General Requirements Market. Documents required for Listing on the JSE Articles of Incorporation Prospectus / Offer Document Full details of the requirements for admission JSE Listing Process and ongoing compliance for the Main and Junior Listing Agreements Market Companies are set out in the Market Audited Financial Statements Rules of the Main and Junior Markets which are available on www.jamstockex.com or email Governance Matters [email protected]. Board of Directors Audit Committee (Majority non-independent directors) The JSE looks forward to discussing the listing Remuneration Committee (Junior Market only) process with you with a view to bringing you on Mentor (Junior Market only) board. Please visit our website for further infor- mation www.jamstockex.com or please email : Timelines [email protected] to make an Submission of Prospectus at least 21 days before final docu- appointment to discuss admission to the Main, 40 Harbour Street, Kingston ment Junior, USD Equities and Bond Market. -

Short Sale Position and Transaction Reporting

Short Sale Position and Transaction Reporting As Required by Section 417 of the Dodd‐Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act This is a report of a study by the Staff of the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The Commission has expressed no view regarding the analysis, findings, or conclusions contained herein. June 5, 2014 Executive Summary Congressional Mandate The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (the “Dodd-Frank Act” or “Act”) was signed into law on July 21, 2010.1 Section 417(a)(2) of the Act directs the Division of Risk, Strategy, and Financial Innovation (the “Division” and now called the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis) of the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “Commission”) to conduct a study of the feasibility, benefits, and costs of: (A) requiring the reporting of short sale positions in publicly listed securities in real time, (i) publicly or, in the alternative, (ii) only to the Commission and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”), and of the feasibility, benefits, and costs of: (B) conducting a voluntary pilot program in which public companies will agree to have all trades of their shares marked (i) “short” (ii) “market maker short” (iii) “buy” (iv) “buy-to-cover” or (v) “long” and reported as such in real time through the Consolidated Tape.2 This is the report of that study made to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the Senate and the Committee on Financial Services of the House of Representatives specified in Section 417(b)(2) of the Act. -

Guide to Going Public Strategic Considerations Before, During and Post-IPO Contents

Guide to going public Strategic considerations before, during and post-IPO Contents 1 | Guide to going public Foreword For private companies seeking to raise capital and capital-held companies considering their strategic options for funding for provide exits for their shareholders, an initial public growth, including a public listing. We have professionals with extensive, offering (IPO) can be a superior route and strategic proven experience with domestic and international capital markets. Our professionals have deep knowledge of your industry, which allows us to option to funding growth and to access deep pools of create interdisciplinary teams that will steer you onward, through and liquidity. While challenging markets will come and go, beyond your IPO and support your plans for growth. it’s the companies that are fully prepared that will We are confident this Guide to going public will give you an initial overview best be able to create value and fully leverage the and checklists of the key phases in going public from a global perspective. IPO windows of opportunity whenever they are open. It is based on EY insights from many IPO transactions, to help you begin Companies that have completed a your IPO value journey, so that you are well prepared to transform your successful IPO know the process private company into a successful public company that continually delivers The companies that involves the complete transformation value to its shareholders. With more than 30 years’ experience helping of the people, processes and culture companies prepare, grow and adapt to life as a public entity, we are well- are fully prepared will be of the organization from a private suited to take you on your IPO journey providing tailored support and enterprise to a public one.