Environmental Health Criteria 125 Platinum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oxidizing Behavior of Some Platinum Metal Fluorides

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title THE OXIDIZING BEHAVIOR OF SOME PLATINUM METAL FLUORIDES Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/46b5r4v5 Author Graham, Lionell Publication Date 1978-10-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LBL-8088.c,y '': ·,~, . ' '~~.. .· J!' ... THE OXIDIZING BEHAV!OROF SOME PLATINUM METAL FLUORIDES . Li onell Graham. · (Ph~ D. Thesis ) IIi !l1/ "~ · r-,> ·1cr7o October 1978 ~t .. ~, ~L l ... ;,() · .. t .. J r.~~ r: !\ ~;~, ·l .• ~~:J"~~ t~J ;,~.)(·_ .. {·~ tJ 1v~ ;;:: r~- J··r·r,;~ Ei:~-:·~,:~~ <'11 ().i\{ Prep~red for the .. U. S. Department of Energy. under Contract W~7405~ENG-48 TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY This is a Library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. .. ' ·t•·! •. ·. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Diu is ion, Ext. 6782 .. LEGAL NOTICE -___,..-----~__, This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government Neither the United States nor the Depart ment of Energy, nor any of their employees, nor any of their con tractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warraf')ty, express or implied,orassumes any legal liabii bility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of nformation, appa- ratus, product. ·· · · disclosed; or rep ·. ts that its use would. not infringe p. · · owned rights ... -i- THE OXIDIZING BEHAVIOR OF SOME PLATINUM METAL FLUORIDES Contents Abstract . v I. General Introduction 1 II. General Apparatus and Handling Techniques 2 A. Apparatus . 2 1. General 2 2. The Cryogenic Technology, Inc., Model 21 Cryo-Cooler .. 3 3. Reactor for Gas-Gas Reaction Products 5 B. -

Chemistry of the Noble Gases*

CHEMISTRY OF THE NOBLE GASES* By Professor K. K. GREE~woon , :.\I.Sc., sc.D .. r".lU.C. University of N ewca.stle 1tpon Tyne The inert gases, or noble gases as they are elements were unsuccessful, and for over now more appropriately called, are a remark 60 years they epitomized chemical inertness. able group of elements. The lightest, helium, Indeed, their electron configuration, s2p6, was recognized in the gases of the sun before became known as 'the stable octet,' and this it was isolated on ea.rth as its name (i]A.tos) fotmed the basis of the fit·st electronic theory implies. The first inert gas was isolated in of valency in 1916. Despite this, many 1895 by Ramsay and Rayleigh; it was named people felt that it should be possible to induce argon (apy6s, inert) and occurs to the extent the inert gases to form compounds, and many of 0·93% in the earth's atmosphere. The of the early experiments directed to this end other gases were all isolated before the turn have recently been reviewed.l of the century and were named neon (v€ov, There were several reasons why chemists new), krypton (KpVn'TOV, hidden), xenon believed that the inert gases might form ~€vov, stmnger) and radon (radioactive chemical compounds under the correct con emanation). Though they occur much less ditions. For example, the ionization poten abundantly than argon they cannot strictly tial of xenon is actually lower than those of be called rare gases; this can be illustrated hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, fl uorine and by calculating the volumes occupied a.t s.t.p. -

The Noble Gases

INTERCHAPTER K The Noble Gases When an electric discharge is passed through a noble gas, light is emitted as electronically excited noble-gas atoms decay to lower energy levels. The tubes contain helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon. University Science Books, ©2011. All rights reserved. www.uscibooks.com Title General Chemistry - 4th ed Author McQuarrie/Gallogy Artist George Kelvin Figure # fig. K2 (965) Date 09/02/09 Check if revision Approved K. THE NOBLE GASES K1 2 0 Nitrogen and He Air P Mg(ClO ) NaOH 4 4 2 noble gases 4.002602 1s2 O removal H O removal CO removal 10 0 2 2 2 Ne Figure K.1 A schematic illustration of the removal of O2(g), H2O(g), and CO2(g) from air. First the oxygen is removed by allowing the air to pass over phosphorus, P (s) + 5 O (g) → P O (s). 20.1797 4 2 4 10 2s22p6 The residual air is passed through anhydrous magnesium perchlorate to remove the water vapor, Mg(ClO ) (s) + 6 H O(g) → Mg(ClO ) ∙6 H O(s), and then through sodium hydroxide to remove 18 0 4 2 2 4 2 2 the carbon dioxide, NaOH(s) + CO2(g) → NaHCO3(s). The gas that remains is primarily nitrogen Ar with about 1% noble gases. 39.948 3s23p6 36 0 The Group 18 elements—helium, K-1. The Noble Gases Were Kr neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and Not Discovered until 1893 83.798 radon—are called the noble gases 2 6 4s 4p and are noteworthy for their rela- In 1893, the English physicist Lord Rayleigh noticed 54 0 tive lack of chemical reactivity. -

CHEMISTRY B (SALTERS) F331 Chemistry for Life *OCE/25640* Candidates Answer on the Question Paper

ADVANCED SUBSIDIARY GCE CHEMISTRY B (SALTERS) F331 Chemistry for Life *OCE/25640* Candidates answer on the question paper. Thursday 13 January 2011 Morning OCR supplied materials: • Data Sheet for Chemistry B (Salters) (inserted) Duration: 1 hour 15 minutes Other materials required: • Scientific calculator *F331* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • The insert will be found in the centre of this document. • Write your name, centre number and candidate number in the boxes above. Please write clearly and in capital letters. • Use black ink. Pencil may be used for graphs and diagrams only. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. If additional space is required, you should use the lined pages at the end of this booklet. The question number(s) must be clearly shown. • Answer all the questions. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. • Where you see this icon you will be awarded marks for the quality of written communication in your answer. This means for example you should: • ensure that text is legible and that spelling, punctuation and grammar are accurate so that meaning is clear; • organise information clearly and coherently, using specialist vocabulary when appropriate. • You may use a scientific calculator. • A copy of the Data Sheet for Chemistry B (Salters) is provided as an insert with this question paper. • You are advised to show all the steps in any calculations. -

DECOS and NEG Basis for an Occupational Standard Platinum

1997:14 DECOS and NEG Basis for an Occupational Standard Platinum Birgitta Lindell Nordic Council of Ministers arbete och hälsa vetenskaplig skriftserie ISBN 91–7045–420–5 ISSN 0346–7821 National Institute for Working Life National Institute for Working Life The National Institute for Working Life is Sweden's center for research and development on labour market, working life and work environment. Diffusion of infor- mation, training and teaching, local development and international collaboration are other important issues for the Institute. The R&D competence will be found in the following areas: Labour market and labour legislation, work organization and production technology, psychosocial working conditions, occupational medicine, allergy, effects on the nervous system, ergonomics, work environment technology and musculoskeletal disorders, chemical hazards and toxicology. A total of about 470 people work at the Institute, around 370 with research and development. The Institute’s staff includes 32 professors and in total 122 persons with a postdoctoral degree. The National Institute for Working Life has a large international collaboration in R&D, including a number of projects within the EC Framework Programme for Research and Technology Development. ARBETE OCH HÄLSA Redaktör: Anders Kjellberg Redaktionskommitté: Anders Colmsjö, Elisabeth Lagerlöf och Ewa Wigaeus Hjelm © Arbetslivsinstitutet & författarna 1997 Arbetslivsinstitutet, 171 84 Solna, Sverige ISBN 91–7045–420–5 ISSN 0346-7821 Tryckt hos CM Gruppen Preface An agreement has been signed by the Dutch Expert Committee for Occupational Standards (DECOS) of the Dutch Health Council and the Nordic Expert Group for Criteria Documentation of Health Risks from Chemicals (NEG). The purpose of the agreement is to write joint scientific criteria documents which could be used by the national regulatory authorities in both the Netherlands and in the Nordic Countries. -

THE FLUORIDES of PLATINUM and R E L a T E D Compounds by DEREK HARRY LOHMANN B.Sc, University of London, 1953 M.Sc, Queen's Univ

THE FLUORIDES OF PLATINUM and related compounds by DEREK HARRY LOHMANN B.Sc, University of London, 1953 M.Sc, Queen's University, Ontario, 1959 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of CHEMISTRY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1961, In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that- permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of CHEMISTRY The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date 31st October 1961. %\\t Pntesttg of ^irtttslj Columbia FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PUBLICATIONS oi . I. "Polar effects in Hydrogen abstraction reactions," M. P. Godsay, DEREK HARRY LOHMANN D. H. Lohmann and K. E. Russell, Chem. and Ind., 1959, 1603. B.Sc, University of London, 1953 M.Sc, Queen's University, Ontario, 1959 2. "Two new fluorides of Platinum," N. Bartlett and D. H. Lohmann, Proc. Chem. Soc, 1960, 14. TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 28th, 1961, AT 1:00 P.M. 3. "The reaction of 2,2-Diphenyl-l-Picrylhydrazyl with 9,10-Dihy- droanthracene and 1,4-Dihydronaphthalene," I. -

Platinum 1 Platinum

Platinum 1 Platinum Platinum Pt 78 iridium ← platinum → goldPd ↑ Pt ↓ Ds Platinum in the periodic table Appearance grayish white General properties Name, symbol, number platinum, Pt, 78 Pronunciation /ˈplætɨnəm/ Element category transition metal Group, period, block 10, 6, d Standard atomic weight 195.084 Electron configuration [Xe] 4f14 5d9 6s1 2, 8, 18, 32, 17, 1 History Discovery Antonio de Ulloa (1735) First isolation Antonio de Ulloa (1735) Physical properties Phase solid Density (near r.t.) 21.45 g·cm−3 Platinum 2 Liquid density at m.p. 19.77 g·cm−3 Melting point 2041.4 K, 1768.3 °C, 3214.9 °F Boiling point 4098 K, 3825 °C, 6917 °F Heat of fusion 22.17 kJ·mol−1 Heat of vaporization 469 kJ·mol−1 Molar heat capacity 25.86 J·mol−1·K−1 Vapor pressure P (Pa) 1 10 100 1 k 10 k 100 k at T (K) 2330 (2550) 2815 3143 3556 4094 Atomic properties Oxidation states 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, −1, −2 (mildly basic oxide) Electronegativity 2.28 (Pauling scale) Ionization energies 1st: 870 kJ·mol−1 2nd: 1791 kJ·mol−1 Atomic radius 139 pm Covalent radius 136±5 pm Van der Waals radius 175 pm Miscellanea Crystal structure face-centered cubic Magnetic ordering paramagnetic Electrical resistivity (20 °C) 105 nΩ·m Thermal conductivity 71.6 W·m−1·K−1 Thermal expansion (25 °C) 8.8 µm·m−1·K−1 Speed of sound (thin rod) (r.t.) 2800 m·s−1 Tensile strength 125-240 MPa Young's modulus 168 GPa Shear modulus 61 GPa Bulk modulus 230 GPa Poisson ratio 0.38 Mohs hardness 4–4.5 Vickers hardness 549 MPa Brinell hardness 392 MPa CAS registry number 7440-06-4 Platinum 3 Most stable isotopes Main article: Isotopes of platinum iso NA half-life DM DE (MeV) DP 190Pt 0.014% 6.5×1011 y α 3.252 186Os 192Pt 0.782% >4.7×1016 y (α) 2.4181 188Os 193Pt syn 50 y ε - 193Ir 194Pt 32.967% - (α) 1.5045 190Os 195Pt 33.832% - (α) 1.1581 191Os 196Pt 25.242% - (α) 0.7942 192Os 198Pt 7.163% >3.2×1014 y (α) 0.0870 194Os (β−β−) 1.0472 198Hg Decay modes in parentheses are predicted, but have not yet been observed Platinum is a chemical element with the chemical symbol Pt and an atomic number of 78. -

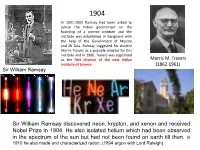

Sir William Ramsay Discovered Neon, Krypton, and Xenon and Received Nobel Prize in 1904

1904 In 1901-1902 Ramsay had been asked to advise the Indian government on the founding of a science institute and the institute was established in Bangalore with the help of the Government of Mysore and JN Tata. Ramsay suggested his student Morris Travers as a possible director for this institute and in 1906, Travers was appointed as the first director of the new Indian Morris M. Travers Institute of Science (1862-1961) Sir William Ramsay Sir William Ramsay discovered neon, krypton, and xenon and received Nobel Prize in 1904. He also isolated helium which had been observed in the spectrum of the sun but had not been found on earth till then. In 1910 he also made and characterized radon. (1894 argon with Lord Raleigh) •The relative abundance of rare gases in the atmosphere decreases in the order Ar>Ne>He> Kr/Xe>Rn. •Among the rare gases except for helium and neon all other rare gases have been made to undergo reactions leading to novel compounds. •These compounds are neutral, anionic and cationic as well as where a rare gas acts as a donor ligand or the substituent on a rare gas compound acts as a ligand. •Most of the rare gas compounds are endothermic and often oxidizing in nature. •The stabilization of rare gas compounds have been mostly achieved by high electro negative substituents such as F, O, Cl or anions having high group electro negativities ( e.g. teflate anion F5TeO- E.N. 3.87) •The very low bond enthalpy and high standard reduction potential of many of the rare gas compounds make them very strong oxidizers. -

Facts on File DICTIONARY of INORGANIC CHEMISTRY

The Facts On File DICTIONARY of INORGANIC CHEMISTRY The Facts On File DICTIONARY of INORGANIC CHEMISTRY Edited by John Daintith ® The Facts On File Dictionary of Inorganic Chemistry Copyright © 2004 by Market House Books Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Facts on File dictionary of inorganic chemistry / edited by John Daintith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8160-4926-2 (alk. paper). 1. Chemistry—Dictionaries. I. Title: Dictionary of inorganic chemistry. II. Daintith, John. XXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXX Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Compiled and typeset by Market House Books Ltd, Aylesbury, UK Printed in the United States of America MP 10987654321 This book is printed on acid-free paper CONTENTS Preface vii Entries A to Z 1 Appendixes I. The Periodic Table 244 II. The Chemical Elements 245 III. The Greek Alphabet 247 IV. Fundamental Constants 247 V. Webpages 248 Bibliography 248 PREFACE This dictionary is one of a series covering the terminology and concepts used in important branches of science. -

Classification of Hazardous Materials

CLASSIFICATION OF HAZARDOUS MATERIALS Contents 1 Allergens and Sensitizers .................................................................................................... 3 2 Anesthetics ......................................................................................................................... 3 3 Asphyxiates ........................................................................................................................ 3 4 Biological Hazards .............................................................................................................. 4 5 Carcinogens ........................................................................................................................ 4 6 Compressed gas ................................................................................................................. 5 7 Corrosives ........................................................................................................................... 6 Health Consequences .................................................................................................. 7 Special Precautions for Hydrogen Fluoride / Hydrofluoric Acid .................................... 7 8 Cryogenic Materials ............................................................................................................ 7 9 Environmental Toxins.......................................................................................................... 8 10 Flammable and Combustible Liquids .............................................................................. -

Platinum Metals Review

PLATINUM METALS REVIEW A quarterly survey of research on the platinum metals and of developments in their applications in industry VOL. 12 OCTOBER 1968 NQ. 4 Conten fs Sliding Noble Metal Contacts Platinum Metal Contacts Nitrosyl Complexes of the Platinum Metals Phase Equilibria in the Platinum-Molybdenum System Phosphine Complexes of Khodium and Ruthenium as Homogeneous Catalysts Fourth International Congress on Catalysis Therrnochemistry of the Platinum Metals and their Compounds One Million Ounces of Platinum Hydrogen in Palladium and its Alloys Hydrogen Diffusion through Rhodium-Palladium Alloys The First Platinum Refiners Abstracts New Patents Index to Volume 12 Communications should be addressed to The Editor, Platinum Metals Reviau Johnson, Matthey & Co., Limited, Halton Garden, London, E.C.1 Sliding Noble Metal Contacts CONTACT RESISTANCE AND WEAR CHARACTERISTICS OF SOME NEW PALLADIUM ALLOY SLIDEWIRES By A. S. Darling, Ph.D., A.M.I.Mech.E., and G. L. Selnian, BS~. Research Laboratories, Johnson Matthey & Co Limited stationary wiper to establish the necessary Vhen, as in many low torgue potentio- sliding contact. meters, contact pressures must not The wiper wire is approximately 0.010inch exceed a feu' grams the use of noble in diameter and contact pressures, in the metals for both resistance mire and range from 0.1 to 10 grams, are adjusted by wiping coratact becomes almost essential. lowering the pendulum suspension until As the factors that determine the elw flexure of the cantilever produces the load trical and mechanical behaviour of such required. After such adjustment the pendu- lotv load sliding contacts have not yc.t lum is rigidly clamped so that well defined been pstablished, zuiperlslidetoire corn- wear tracks are obtained on the wire under binations are still selected on an em- test when the bobbin is reciprocated. -

Platinum and Platinum Compounds

Platinum and platinum compounds Health-based recommended occupational exposure limit Gezondheidsraad Voorzitter Health Council of the Netherlands Aan de minister van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid Onderwerp : Aanbieding advies Platinum and platinum compounds Uw kenmerk : DGV/MBO/U-932542 Ons kenmerk : U-5204/HS/pg/459-R56 Bijlagen : 1 Datum : 12 juni 2008 Geachte minister, Graag bied ik u hierbij het advies aan over de beroepsmatige blootstelling aan platina en platinaverbindingen. Het maakt deel uit van een uitgebreide reeks, waarin gezondheids- kundige advieswaarden worden afgeleid voor concentraties van stoffen op de werkplek. Dit advies over platina en platinaverbindingen is opgesteld door de Commissie Gezondheid en Beroepsmatige Blootstelling aan Stoffen (GBBS) van de Gezondheidsraad en beoordeeld door de Beraadsgroep Gezondheid en Omgeving. Ik heb dit advies vandaag ter kennisname toegezonden aan de minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport en aan de minister van Ruimte en Milieu. Hoogachtend, prof. dr. J.A. Knottnerus Bezoekadres Postadres Parnassusplein 5 Postbus 16052 2511 VX Den Haag 2500 BB Den Haag Telefoon (070) 340 70 04 Telefax (070) 340 75 23 E-mail: [email protected] www.gr.nl Platium and platinum compounds Health-based recommended occupational exposure limit to: the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport No. 2008/12OSH, The Hague, June 12, 2008 The Health Council of the Netherlands, established in 1902, is an independent scientific advisory body. Its remit is “to advise the government and Parliament on the current level of knowledge with respect to public health issues...” (Section 22, Health Act). The Health Council receives most requests for advice from the Ministers of Health, Welfare & Sport, Housing, Spatial Planning & the Environment, Social Affairs & Employment, and Agriculture, Nature & Food Quality.