Ofportuguese History Table of Contents Volume 14, Number 1, June 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Two-Popes-Ampas-Script.Pdf

THE TWO POPES Written by Anthony McCarten Pre-Title: Over a black screen we hear the robotic voice of a modern telephone system. VOICE: Welcome to Skytours. For flight information please press “1”. If you’re calling about an existing booking please press “2”. If you’re calling about a new booking please press “3” ... The beep of someone (Bergoglio) pressing a button. VOICE: (CONT’D) Did you know that you can book any flight on the Skytour website and that our discount prices are internet only ... BERGOGLIO: (V.O.) Oh good evening I ... oh. He’s mistaken this last for a human voice but ... VOICE: (V.O.) ... if you still wish to speak to an operator please press one ... Another beep. VOICE : (V.O.) Good morning welcome to the Skytours sales desk ... BERGOGLIO: (V.O.) Ah. Yes. I’m looking for a flight from Rome to Lampedusa. Yes I know I could book it on the internet. I’ve only just moved here. VOICE: Name? BERGOGLIO: Bergoglio. Jorge Bergoglio. VOICE: Like the Pope. 1 BERGOGLIO: Well ... yes ... in fact. VOICE: Postcode? BERGOGLIO: Vatican city. There’s a long pause. VOICE: Very funny. The line goes dead. Title: The Two Popes. (All the scenes that take place in Argentina are acted in Spanish) EXT. VILLA 21 (2005) - DAY A smartly-dressed boy is walking along the narrow streets of Villa 21 - a poor area that is exploding with music, street vendors, traffic. He struts past the astonishing murals that decorate the walls of the area. The boy is heading for an outdoor mass, celebrated by Archbishop Bergoglio. -

Iberian Books: La Compilación De Un Catálogo De Títulos Abreviados En La Era Digital

Iberian Books: la compilación de un catálogo de títulos abreviados en la era digital Iberian Books: Compiling a Short Title Catalogue in the Digital Age Alexander S. Wilkinson University College Dublin, Irlanda Alejandra Ulla Lorenzo Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, España Recepción 16.01.18 / Aceptación 21.06.18 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/iib.bibliographica.2018.2.30 Resumen El propósito del artículo consiste en exponer los orígenes, estado actual y pers- pectivas futuras del proyecto Iberian Books. Su objetivo principal es la creación de un catálogo de títulos abreviados de todos los libros publicados en España, Portugal y el Nuevo Mundo, o fuera de estas fronteras geográficas pero en len- gua ibérica, entre 1472 y 1700. Asimismo, ofrece un panorama de los proyectos secundarios que, al hilo del mencionado, han surgido en el contexto del equipo: el primero se refiere a la visualización de datos sobre mapas y el segundo está relacionado con la creación de un repertorio digital de imágenes contenidas en libros impresos en la temprana edad moderna. La sociedad digital ha permitido, en definitiva, ofrecer una serie de herramientas que otorgarán un nuevo trazado de la industria del libro ibérico durante ese periodo. Palabras Libros ibéricos; catálogo de títulos abreviados; visualizaciones de datos; cultura clave visual; reconocimiento de imágenes. Abstract The purpose of this article is to outline the origins, current status and future direc- tion of Iberian Books. The core ambition of the project is to create a foundational short title catalogue of all books printed in Spain, Portugal and the New World, or published elsewhere in an Iberian language, between 1472 and 1700. -

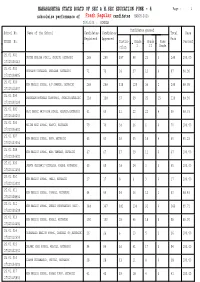

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 289 289 197 66 23 3 289 100.00 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 71 71 24 27 12 4 67 94.36 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 288 288 118 129 36 2 285 98.95 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 118 118 37 39 25 15 116 98.30 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 61 60 11 22 22 4 59 98.33 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 70 38 26 6 0 70 100.00 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 65 63 16 30 10 4 60 95.23 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 67 67 17 39 11 0 67 100.00 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 65 65 38 24 3 0 65 100.00 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 17 17 8 6 3 0 17 100.00 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 64 64 14 36 12 1 63 98.43 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 348 347 181 134 31 0 346 99.71 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 100 100 29 46 18 6 99 99.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 6 13 5 2 26 100.00 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 94 94 36 41 17 0 94 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 28 28 13 11 4 0 28 100.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 41 41 19 18 4 0 41 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Mmtc Unpaid Dividend 30092013

FNAME MNAME LNAME FHFNAME FHMNAME FHLNAME ADD COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT PIN FOLIO INVST AMOUNT DATE PARVEZ ANSARI NA NA Indra Nagar Bhel Jhansi U P INDIA Uttar Pradesh Jhansi 1201320000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 282523 and Unpaid Dividend ZACHARIAH THOMAS NA NA Po Box 47257 Fahaheel KUWAIT NA 9NRI9999 1304140005 Amount for Unclaimed 12.00 30-Oct-2016 Fahaheel Kuwait 656021 and Unpaid Dividend ANKUR VILAS KULKARNI NA NA 25, River Dr South, Aptmt # UNITED NA 9NRI9999 1203440000 Amount for Unclaimed 16.00 30-Oct-2016 2511, Jersey City, Jersey Nj STATES OF 062447 and Unpaid Dividend Usa AMERICA ERAM HASHMI NA NA House No-3031 Kaziwara INDIA Delhi 110002 IN30011811 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Darya Ganj New Delhi 249819 and Unpaid Dividend DURGA DEVI NA NA 451- Robin Cinema, Subzi INDIA Delhi 110007 1201911000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Mandi Delhi Delhi 017111 and Unpaid Dividend SOM DUTT DUEVEDI NA NA D-5/5, Ii Nd Floor Rana INDIA Delhi 110007 1203450000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Pratap Bagh New Delhi 443528 and Unpaid Dividend Delhi SUNIL GOYAL NA NA D 27 Cc Colony Opp Rana INDIA Delhi 110007 IN30114310 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Pratap Bagh New Delhi 427000 and Unpaid Dividend AVM ENTERPRISES PVTLTD NA NA F 40, Okhla Ind Area Phase I INDIA Delhi 110020 IN30105510 Amount for Unclaimed 8.00 30-Oct-2016 New Delhi 266034 and Unpaid Dividend 30-Oct-2016 SUDARSHA H-80 Shivaji Park Punjabi IN30011811 Amount for Unclaimed GURPREET SINGH MEHTA N SINGH MEHTA Bagh New Delhi INDIA Delhi 110026 065484 -

Federico Palomo (Ed.) La Memoria Del Mundo: Clero, Erudición Y Cultura Escrita En El Mundo Ibérico (Siglos XVI-XVIII)

Federico Palomo (ed.) La memoria del mundo: clero, erudición y cultura escrita en el mundo ibérico (siglos XVI-XVIII). Cuadernos de Historia Moderna. Anejos. Serie Monografías, XIII (2014). ISBN: 9788466934930 Bruno Feitler1 It was part of the strategies adopted by every important family in the Iberian Ancien Régime, whenever possible, to dedicate one or more of their children to the Church. Such ordinations were the result of specific vows, strategies of prestige, or simply a way of keeping the family estate undivided. More than one foreign traveler, in his chronicles, drew attention to the high proportion of priests, friars and nuns among the population of Lisbon, for example. Because of their number, but mainly because of their specific status and the role they played, the men and women of the Church constituted an important social group in Iberian society. They deeply influenced the economy and politics of those kingdoms, not to mention the obvious religious and disciplinary roles that they played. Furthermore, between 1500 and 1520, 40% of the books printed in the Iberian Peninsula were religious ones (not taking into account Bibles, but including printed papal bulls). According to Wilkinson, this ratio increased to 46% between 1580 and 1600. Obviously, the men and women of the Church did not write works (printed or handwritten) that were related solely to religious subjects, yet, nevertheless, both these population numbers and publishing data pinpoint the importance of religion, and consequently of the clergy, in the written culture of the Iberian early modern world. The volume edited by Federico Palomo and entitled The Memory of the World: Clergy, Erudition and Written Culture in the Iberian World (16th-18th centuries) provides us with an innovative discussion of the role played by clerics in the production, circulation and eventual printed publication of texts about a broad series of subjects during the Iberian early modern period, ranging from theology to comedies, or from chronicles to scientific treaties. -

L'est INSULINDIEN

Etudes interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien Sous le patronage de l' Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales ARCHIPEL 90 L'EsT INSULINDIEN 2015 Revu e SOU1CT1 l1C par l' Institut des Science s Humaines et Sociales du CNRS l'Instiuu francais dT ndones ie c l l' Institu t des Langues et Civ ilisations Orientales L 'EST INSULINDIEN Sous la direction de Dana Rappoport et Dominique Guillaud Sommaire INTRODUCTION 3 Dana Rappoport et Dominique Guillaud Reconsiderer r Est insulindien Du PEUPLEMENT A L'ECRITURE DE L'HISTOIRE 15 Susan O'Connor Rethinking the Neolithic in Island Southeast Asia, with Particular Reference to the Archaeology ofTimor-Leste and Sulawesi 49 Jean-Christophe Galipaud Reseaux neolithiques, nomades marins et marchands dans les petites lies de la Sonde 75 Hans Hagerdal Eastern Indonesia and the Writing ofHistory VERS UNE DEFINITION DE L'INSULINDE ORIENTALE 99 Antoinette Schapper Wallacea, a Linguistic Area 153 Philip Yampolsky Is Eastern Insulindia a Distinct Musical Area? AIRE DE TRANSITION OU CREUSET ? SOCIETES, TECHNIQUES, TERRITOIRES ET RITUELS 189 lames Fox Eastern Indonesia in Austronesian Perspective: The Evidence of Relational Terminologies Archipel90, Paris, 2015, p. 1-2 217 Cecile Barraud Parente, alliance. maisons dans l' Est insulindien : rcode neerlandaise et sa posterite critique 245 Dominique Guillaud Le vivrier et le sacre. Systemes agricoles, rituels et territoires dans TEst indonesien et aTimor-Leste 275 Dana Rappoport Musique et rituel dans I'Est insulindien (Indonesie orientate et Timor-Leste) : premierjalons 307 Ruth Barnes Textiles East ofthe Wallace Line. A Comparative Approach to Pattern and Technique RI;:SLJM~;S - ABSTRACTS (<:) Copyright Association Archipe12015 En couverture : Parure de danseuse aSolor Quest. -

Alexander S. Wilkinson and Alejandra Ulla Lorenzo, Eds. Iberian Books Volumes II & III

Alexander S. Wilkinson and Alejandra Ulla Lorenzo, eds. Iberian Books Volumes II & III. Books Published in Spain, Portugal and the New World or Elsewhere in Spanish or Portuguese between 1601 and 1650 Alexander S. Wilkinson and Alejandra Ulla Lorenzo, eds. Iberian Books Volumes II & III. Books Published in Spain, Portugal and the New World or Elsewhere in Spanish or Portuguese between 1601 and 1650 / Libros Ibéricos Volúmenes II y III: Libros publicados en España, Portugal y el Nuevo Mundo o impresos en otros lugares en español o portugués entre 1601 y 1650. Vol. 1: A-E; Vol. 2: F-Z. Leiden: Brill, 2016. Vol. 1: xcii, 1246p., ill.; Vol. 2: xliv, 2510p., ill. ISBN 9789004292291. €450.00. This two-volume set follows the first repertoire in the series compiled by Alexander S. Wilkinson, titled Iberian Books: Books Published in Spanish or Portuguese or on the Iberian Peninsula before 1601 (Leiden: Brill, 2010). All three volumes are bilingual (English-Spanish) and contain bibliographies that order the publications pertaining to the period in question alphabetically by author’s surname. The task is a difficult one to imagine, as the contributors to volumes 2 and 3 not only pursue the inventory of about 45,000 books published in the first half of the seventeenth century, but they also indicate where about 215,000 copies of those SHARP News https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/ | 1 Alexander S. Wilkinson and Alejandra Ulla Lorenzo, eds. Iberian Books Volumes II & III. Books Published in Spain, Portugal and the New World or Elsewhere in Spanish or Portuguese between 1601 and 1650 books reside today. -

EAST TIMOR: REMEMBERING HISTORY the Trial of Xanana Gusmao and a Follow-Up on the Dili Massacre

April 1993 Vol 5. No.8 EAST TIMOR: REMEMBERING HISTORY The Trial of Xanana Gusmao and a Follow-up on the Dili Massacre I. Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Xanana Gusmao and the Charges Against Him ....................................................................... 3 The Charges, 1976-1980................................................................................................................ 3 The June 10, 1980 Attack .............................................................................................................. 4 Peace Talks .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Kraras Massacre ..................................................................................................................... 5 1984 to the Present......................................................................................................................... 6 III. The Xanana Trial......................................................................................................................... 7 Circumstances of Arrest and Detention......................................................................................... 8 Why not subversion? .................................................................................................................... 11 Access to and Adequacy of Legal Defense ................................................................................. -

Shivaji University,Kolhapur Application for Ph.D

Shivaji University,Kolhapur Application for Ph.D. Entrance Examination 2018-2019 Application Number : - 932 Application Number : - 932 Course Name : - Ph.D. Subject : - Bio-Chemistry Exam Center : - Shivaji University,Kolhapur Candidate Name : - KALE SANDIP SHANTARAM Father/Hasband Name : - Shantaram Mother Name Lilabai Current Address : - Dept. of Biochemitry Shivaji University, Kolhapur Pin-416004 Permanent Address : - At-Aldare, Post/Tal- Junnar Dist- Pune (Maharashtra) Pin- 410502 Telephone No. : - Mobile No. : - 8983381329 Email ID : - [email protected] Present Occupation : - Assistant Professor M.Phil Pass : - NO NET Pass : - Yes SET Pass : - Yes SLET Pass : - No GATE Pass : - No UGC-JRF Pass : - No Birthdate : - 28-Mar-1991 Gender : -Male Maritial Status : - UnMarried Caste Category : - ST Physically Handicapped : No Nationality : - Indian Applied For Other Subject : - No Graduation Details : - Name of College / Institute University Examination Passing Seat No. Perc. % Subject Offered Year -SSC college Junnar BSc Chemistry Other 2011 - 68.90 Post Graduation Details : - Name of College / Institute University Examination Passing Seat No. Perc. % Subject Offered Year Dept. of Chemistry, SPPU Biochemistry Other MSc 2013 - 57.35 Fee Details : - Amount Payment Receipt No. Receipt Date Method of payment UTR No. 39175105 600 12808 2018/07/07 02:41:47 PM Debit/Credit Card Shivaji University,Kolhapur Application for Ph.D. Entrance Examination 2018-2019 Application Number : - 1296 Application Number : - 1296 Course Name : - Ph.D. Subject : - Bio-Chemistry Exam Center : - Shivaji University,Kolhapur Candidate Name : - MALI PRATIBHA RAMCHANDRA Father/Hasband Name : - RAMCHANDRA Mother Name KAVERI Current Address : - C/O VANITA S. KADAM,KRISHNAVATI, SR.NO 1 SHIVGANESH COLONY, NAKHATE VASTI,NEAR TAMBHE SCHOOL,RAHATNI, PUNE 411017 Permanent Address : - C/O DADA S. -

Adelante El Divorcio

adelante el divorcio anna franchi introducciÓn, ediciÓn crÍtica y traducciÓn de milagro martÍn clavijo ADELANTE EL DIVORCIO MEMORIA DE MUJER 11 Colección dirigida por Josefina CUESTA (Universidad de Salamanca) & María José TURRIÓN (Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, Salamanca) Consejo científico Virginia ÁVILA (UNAM, México) Dora BARRANCOS (CONICET, Argentina) Christina VON BRAUN (Universidad Humboldt de Berlín, Alemania) Nuria CHINCHILLA (IESE, España) Jean Louis GUEREÑA (Universidad de Tours, Francia) Araceli MANGAS (Universidad Complutense, España) Jane MORRICE (Consejo Económico y Social Europeo, UE) María Jesús PRIETO-LAFFARGUE (Instituto de la Ingeniería de España, ex-Presidenta de la WFEO) ANNA FRANCHI ADELANTE EL DIVORCIO Introducción, edición crítica y traducción de Milagro MARTÍN CLAVIJO ANNA FRANCHI ADELANTE EL DIVORCIO Introducción, edición crítica y traducción dse Milagro MARTÍN CLAVIJO MEMORIA DE MUJER 11 © de esta edición: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca © de la introducción, edición crítica y traducción: Milagro Martín Clavijo 1 ª edición: noviembre, 2018 Motivo de cubierta: El rapto de las sabinas © Emilio Clavijo Cobaleda, 2002 Este libro se enmarca en el proyecto de investigación financiado por la Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Castilla y León y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (SA019P17), con el título “Escritoras inéditas en español en los albores del s. XX (1880-1920). Renovación pedagógica del canon literario” dirigido por la profesora Milagro Martín Clavijo de la Universidad de Salamanca ISBN: 978-84-1311-199-5 (PDF) ISBN: 978-84-1311-200-8 (POD) Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca Plaza San Benito s/n E-37002 Salamanca (España) http://www.eusal.es [email protected] Impreso en España-Printed in Spain Maquetación: Sara Velázquez Realizado: Cícero, S.L. -

For a Better View Staff

FOR A BETTER VIEW STAFF presidente servizio transfer sezione maremetraggio Chiara Valenti Omero Trieste Chauffeured Service, a cura di Chiara Valenti Omero RGrent con la collaborazione di segreteria amministrativa Daniela Crismani, Francesco Martina Parenzan presentazione serate Ruzzier Zita Fusco segreteria organizzativa giuria del premio Oltre il Muro Lisa Lombardini servizio fotografico coordinamento di Davide del Nika Furlani, Jorge Muchut Degan, Ivan Gergolet, Chiara movimento copie e ricerca film Valenti Omero David McConnell, realizzazione premi Vittoria Rusalen Plexistar sezione nuove impronte a cura di Beatrice Fiorentino ufficio ospitalità immagine del festival Vittoria Rusalen Francesco Paolo Cappellotto sezione sweets4kids a cura di Tommaso Gregori ufficio stampa sigla coordinamento di Raffaella Moira Cussigh, Daniela Sartogo Francesco Paolo Cappellotto, Canci Francesco Ruzzier diario di bordo on line shorts goes hungary a cura di Riccardo Visintin stagista a cura di Tiziana Ciancetta, David McConnell Patrizia “Pepi” Gioffrè, Luca catalogo Luisa a cura di David McConnell, responsabile volontari Vittoria Rusalen Lisa Lombardini fatti un film! laboratorio di con la collaborazione di Diego videomaking per bambini e traduzioni Malabotti ragazzi BusinessFirst Trieste, David a cura di Francesco Filippi McConnell volontari Emanuele Biasiol, Emilia realmente liberi grafica coordinata, layout Burgio, Claudia Cera, Gabriella a cura di Andrea Segre catalogo e programma di sala Corrado, Andrea De Marco, coordinamento di Maurizio di Francesco -

Imprints of Devotion: Print and the Passion in the Iberian World (1472-1598)

Imprints of Devotion: Print and the Passion in the Iberian World (1472-1598) By © 2019 Christina Elizabeth Ivers Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chair, Isidro J. Rivera ________________________________ Patricia W. Manning ________________________________ Bruce Hayes ________________________________ Robert Bayliss ________________________________ Jonathan Mayhew ________________________________ Emily C. Francomano Date Defended: May 6, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Christina E. Ivers certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Imprints of Devotion: Print and the Passion in the Iberian World (1472-1598) ________________________________ Chair, Isidro J. Rivera Date approved: May 16, 2019 iii Abstract “Imprints of Devotion: Print and the Passion in the Iberian World (1472-1598)” takes a comparative approach to demonstrate that the printed books at the center of its chapters –La dolorosa passio del nostre redemptor Jesucrist (Barcelona: Pere Posa, 1508), Le premier livre de Amadis de Gaule (Paris: Denis Janot, 1540), and a Latin translation of the Brevísima relación de la destruyción de las Indias (Frankfurt: Theodor de Bry, 1598)– possess shared material elements that either evoke or intentionally depart from typographical conventions that characterize a corpus of late fifteenth-century Iberian devotional literature related to Christ’s Passion. Rather than dismiss such repetitions as arbitrary, I propose they are instances of material intertextuality. In this dissertation, material intertextuality accounts for previous reading, viewing, emotive, and recitative experiences related to Christ’s Passion that readers recalled while interacting with early printed books.