Language Teacher Education ୁઇపઇ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Universities That Offer Teacher-Training Programs

Japanese Universities that Offer Teacher-Training Programs Hokkaido University of Education – http://www.hokkyodai.ac.jp Hirosaki University - http://www.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/kokusai/index.html Iwate University – http://iuic.iwate-u.ac.jp/ Miyagi University of Education – http://www.miyakyo-u.ac.jp Fukushima University – http://www.fukushima-u.ac.jp/ Ibaraki University – http://www.ibaraki.ac.jp/ University of Tsukuba – www.kyouiku.tsukuba.ac.jp www.intersc.tsukuba.ac.jp Utsunomiya University – http://www.utsunomiya-u.ac.jp/ Gunma University – http://www.gunma-u.ac.jp Saitama University – http://www.saitama-u.ac.jp Chiba University – http://www.chiba-u.ac.jp Tokyo University of Foreign Studies – http://www.tufs.ac.jp Tokyo Gakugei University – http://www.u-gakugei.ac.jp/ Yokohama National University – http://www.ynu.ac.jp/english/ Niigata University – http://www.niigata-u.ac.jp/ Joetsu University of Education – http://www.juen.ac.jp/ Akita University – http://www.akita-u.ac.jp/english/ Toyama University – http://www.u-toyama.ac.jp Kanazawa University – http://www.kanazawa-u.ac.jp/e/index.html University of Fukui – http://www.u-fukui.ac.jp University of Yamanashi – http://www.yamanashi.ac.jp/ Shinshu University – http://www.shinshu-u.ac.jp/english/index.html Gifu University – https://syllabus.gifu-u.ac.jp/ Shizuoka University – http://www.shizuoka.ac.jp/ Aichi University of Education – http://www.aichi-edu.ac.jp/ http://www.aichi-edu.ac.jp/cie/ 1 Mie University – http://www.mie-u.ac.jp Shiga University – http://www.shiga-u.ac.jp/ -

University Degree Courses Offered in English 9 : Pre-Arrival Admission (A System Which Enables Intl

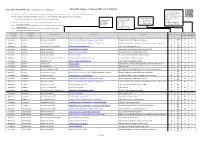

独立行政法人日本学生支援機構(JASSO:Japan student Services Organization) University Degree Courses Offered in English 9 : Pre-Arrival Admission (A system which enables intl. The table below extracts the search results for "English" as "Medium of Instruction" from "University & Junior college School Search" data. students to apply to universities For further inquiries and details regarding the list, please refer to the following website and ask each university directly: and receive entrance permission before arriving in Japan) 6: The academic degree 8: Medium of Instruction Y Yes https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/planning/search-school/daigakukensaku/ 3: University Type which can be awarded E English (100%) N No [N] National B Bachelor E>J English, Japanese S Inquire directly with the Note 1 : To search for certain courses conducted in both English and Japanese, please [L] Local Public M Master (Supplementary) relevant school for details. refer to the link above. [P] Private D Doctor Note 2 : This data is current as of May 2021. Please contact the university directly for the P Professional Degree latest information. M&D Master and Doctor Note 3 : Japanese language proficiency is not required for application (admission), however in some courses it is required. Major Fields Major Fields Medium of Pre-Arrival Univ. Name & Type Course Name1 Course Name2 Degree Begins in of Study of Study Instruction Admission 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 8 9 Apr. 1 : Humanities Literature Utsunomiya University[N] Graduate School of Regional Development and Creativity Division of Advanced Transdisciplinary Science D E>J N Oct. 1 : Humanities Literature Chiba University [N] Graduale Schoolof Humanities and Studies on Public Affairs Department of Humanities and Studies on Public Affairs, Courses of Humanities D Apr. -

Semantic Integration of User Data-Models and Processes

Program Committee CANDAR 2016 Track 1: Algorithms and Applications Chair: Akihiro Fujiwara, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan Stéphane Devismes, VERIMAG UMR 5104, France Man Duhu, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, China Masaru Fukushi, Yamaguchi University, Japan Teofilo Gonzalez, University of California, USA Qianping Gu, Simon Fraser University, Canada Xin Han, Dalian University of Technology, China Fumihiko Ino, Osaka University, Japan Hirotsugu Kakugawa, Osaka University, Japan Sayaka Kamei, Hiroshima University, Japan Christos Kartsaklis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, USA Yosuke Kikuchi, Tsuyama National College of Technology, Japan Yonghwan Kim, Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan Guoqiang Li, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China Yamin Li, Hosei University, Japan Ami Marowka, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Eiji Miyano, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan Hiroaki Mukaidani, Hiroshima University, Japan Takayuki Nagoya, Tottori University of Environmental Studies, Japan Fukuhito Ooshita, NAIST, Japan Ke Qiu, Brock University, Canada Wei Sun, Data61/CSIRO, Australia Daisuke Takafuji, Hiroshima University, Japan Satoshi Taoka, Hiroshima University, Japan Jerry Trahan, Louisiana State University, USA Yushi Uno, Osaka Prefecture University, Japan Shingo Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi University, Japan Hiroshi Yamamoto, Ritsumeikan University, Japan Track 2: Architecture and Computer System Chair: Michihiro Koibuchi, National Institute of Informatics, Japan Martti Forsell, VTT, Finland Ikki Fujiwara, National Institute of Informatics, -

Japanese National Universities N I V E Rs I T Ies

J ap a n ese N a t ional Japanese National Universities U n i v e rs i t ies The Japan Association of National Universities National Center of Sciences Bldg. 4F 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0003, Japan tel : +81-3-4212-3506 fax : +81-3-4212-3509 The Japan Association of National Universities http://www.janu.jp E-mail : [email protected] Data Institutions National National 86 Public 11% Public Private 89 11% Total 779 100% Private 604 78% (Source)MEXT “School Basic Survey 2015” Students 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% National Undergraduate 17.4 5.1 77.5 Public Master 58.8 6.5 34.7 Private Japanese National Universities Doctor 68.6 6.6 24.8 Professional 36.1 4.4 59.5 Total* National Public Private Total 2,805,536 595,759 145,592 2,064,185 Undergraduate 2,556,062 445,668 129,618 1,980,776 Master 158,974 93,416 10,372 55,186 Courses Doctor 73,877 50,676 4,876 18,325 Professional 16,623 5,999 726 9,898 *Total includes National, Public, and Private. Total including advanced course students, spcial course students, listeners, and research students. (Source)MEXT “School Basic Survey 2015” International Students&Foreign Faculties Total* National Public Private International Students Total 105,844 35,490 3,498 66,856 Undergraduate Students 65,865 10,844 1,755 53,266 Graduate Students 39,979 24,646 1,743 13,590 Foreign Faculties Total 20,756 4,850 1,380 14,526 Full-Time Foreign Faculties 7,735 2,574 514 4,647 Part-Time Foreign Faculties 13,021 2,276 866 9,879 *Total includes National, Public, and Private. -

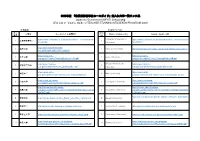

受入れ大学一覧リンク集 Japanese Government (MEXT) Scholarship URL List of 'Course Guide of TEACHER TRAINING STUDENTS PROGRAM 2020'

2020年度 「教員研修留学生コースガイド」受入れ大学一覧リンク集 Japanese Government (MEXT) Scholarship URL List of 'Course Guide of TEACHER TRAINING STUDENTS PROGRAM 2020' 日本語版 English Version 大学 Univ. 大学名 コースガイド掲載URL Name of University Course Guide URL 番号 No https://www.hokkyodai.ac.jp/international/from_overseas/gover Hokkaido University of https://www.hokkyodai.ac.jp/international/from_overseas/gover 1 北海道教育大学 1 nment.html Education nment.html http://www.kokusai.hirosaki- 2 弘前大学 2 Hirosaki University http://www.kokusai.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/en/studyabroad/sa_page7/ u.ac.jp/studyabroad02/sa02_page6/ https://www.iwate- https://www.iwate- 3 岩手大学 3 Iwate University u.ac.jp/iuic/TeacherTrainingStudentsJ%20.pdf u.ac.jp/iuic/english/TeacherTrainingStudentsE.pdf http://www.miyakyo- Miyagi University of http://www.miyakyo- 4 宮城教育大学 4 u.ac.jp/international/course_guide/guide1.pdf Education u.ac.jp/international/course_guide/guide1.pdf https://www.akita- https://www.akita- 5 秋田大学 5 Akita University u.ac.jp/honbu/inter/pdf_class/course_teacher2020.pdf u.ac.jp/honbu/inter/pdf_class/course_teacher2020_en.pdf https://www.yamagata- https://www.yamagata- 6 山形大学 6 Yamagata University u.ac.jp/jp/files/2015/7481/9619/kyokenjapanese.pdf u.ac.jp/jp/files/6815/7481/9627/kyoukenenglish.pdf http://kokusai.adb.fukushima- http://kokusai.adb.fukushima- 7 福島大学 u.ac.jp/newstudents/Files/2019/11/f6c7f009d3c501d028e8d109 7 Fukushima University u.ac.jp/newstudents/Files/2019/11/43af45e87496d688ad4b476 c8b7847a.pdf eed00d266.pdf http://cge.lae.ibaraki.ac.jp/en/to_ibaraki_u/teacher_training.htm 8 茨城大学 -

ICRC 2007 Proceedings

30TH INTERNATIONAL COSMIC RAY CONFERENCE ICRC 2007 Proceedings - Pre-Conference Edition Gamma-hadron separation of parent particles of air showers above several 10 TeV energies using Tibet-III air-shower array THE TIBET ASγ COLLABORATION 1 2 3 4 5 2 5 M. AMENOMORI , X. J. BI , D. CHEN , S. W. CUI , DANZENGLUOBU , L. K. DING , X. H. DING , 6 6 2 7 8 8 5 C. FAN , C. F. FENG , ZHAOYANG FENG , Z. Y. FENG , X. Y. GAO , Q. X. GENG , H. W. GUO , 2 6 9 10 5 2 11 7 H. H. HE , M. HE , K. HIBINO , N. HOTTA , HAIBING HU , H. B. HU , J. HUANG , Q. HUANG , 7 12 13 3 14 11 5 H. Y. JIA , F. KAJINO , K. KASAHARA , Y. KATAYOSE , C. KATO , K. KAWATA , LABACIREN , 15 6 6 16 2 2 5 13 17 G. M. LE , A. F. LI , J. Y. LI , Y.-Q. LOU , H. LU , S. L. LU , X. R. MENG , K. MIZUTANI ; , 8 14 18 1 19 11 20 J. MU , K. MUNAKATA , A. NAGAI , H. NANJO , M. NISHIZAWA , M. OHNISHI , I. OHTA , 17 9 11 2 21 22 12 H. ONUMA , T. OUCHI , S. OZAWA , J. R. REN , T. SAITO , T. Y. SAITO , M. SAKATA , 11 3 9 11 9 23 11 2 T. K. SAKO , M. SHIBATA , A. SHIOMI ; , T. SHIRAI , H. SUGIMOTO , M. TAKITA , Y. H. TAN , 9 13 24 11 8 2 11 N. TATEYAMA , S. TORII , H. TSUCHIYA , S. UDO , B. WANG , H. WANG , X. WANG , 2 6 2 6 12 11 8 Y. -

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (National)

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Field of Study Agricultural Development Tokyo University of Agriculture and University Technology (National) Graduate School Graduate School of Agriculture URL of University http://www.tuat.ac.jp/en/index.html http://www.tuat.ac.jp/en/department/graduate_school/nouga URL of Graduate School kuhu Department of International Environmental and Agricultural 1 Program name Sciences (IEAS), Special Course URL of Program http://www.tuat.ac.jp/~ieas/index.html Degrees Master of Agriculture Credit and years needed 32 Credits, 2 Years for graduation Additional credits will be required for the certificate of Note “Education Program for Field-Oriented Leaders in Environmental Sectors in Asia and Africa”. 2. Features of University The history of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) goes back to 1874 when it was Agricultural Training Institute and Silkworm Disease Experiment Section in the Ministry of Home Affair. These two institutions had each own history and they were developed to Tokyo College of Agriculture and Forestry and Tokyo Textile College in 1944. Then, in 1949, under the modern university systems, the two colleges were unified to Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. In 2004, TUAT was transformed to National University Corporation, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. TUAT has two campuses (see Fig. 1): Fuchu Campus for Institute of Agriculture (Land area about 280,000 m2) and Koganei Campus for Institute of Engineering (Land area about 160,000 m2). Both -

1. Japanese National, Public Or Private Universities

1. Japanese National, Public or Private Universities National Universities Hokkaido University Hokkaido University of Education Muroran Institute of Technology Otaru University of Commerce Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Kitami Institute of Technology Hirosaki University Iwate University Tohoku University Miyagi University of Education Akita University Yamagata University Fukushima University Ibaraki University Utsunomiya University Gunma University Saitama University Chiba University The University of Tokyo Tokyo Medical and Dental University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku (Tokyo University of the Arts) Tokyo Institute of Technology Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology Ochanomizu University Tokyo Gakugei University Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology The University of Electro-Communications Hitotsubashi University Yokohama National University Niigata University University of Toyama Kanazawa University University of Fukui University of Yamanashi Shinshu University Gifu University Shizuoka University Nagoya University Nagoya Institute of Technology Aichi University of Education Mie University Shiga University Kyoto University Kyoto University of Education Kyoto Institute of Technology Osaka University Osaka Kyoiku University Kobe University Nara University of Education Nara Women's University Wakayama University Tottori University Shimane University Okayama University Hiroshima University Yamaguchi University The University of Tokushima Kagawa University Ehime -

UNIVERSITY of TOYAMA ( Toyama ) ●

UNIVERSITY OF TOYAMA ( Toyama ) ● 1. Students and researchers can learn extensively about Japanese educational systems from primary to graduate schools in collaboration with institutional facilities such as the attached schools. 2. They can also learn about the various cultures of the areas that surround the Sea of Japan. 3. They can also learn about the natural environment of Toyama, ranging from the sea areas to the high-mountain areas. ◇ University of Toyama Overview ◇ Outline of Teacher Training Program ◇Others 1. Characteristics and Outline 1. Program Features 1. Housing In October 2005, three universities (Toyama University (Established in 1949), Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical An academic international student, taking his/her interests International students live in International House and University (Established in 1975) and Takaoka National into adviser will organize a curriculum for an consideration. in privately owned apartments. College (Established in 1983)) were integrated into Students and researchers can learn extensively about The International House (Gofuku) has 34 indevidual University of Toyama. It is a national university with a wide Japanese educational systems from primary to graduate rooms. The lodgings costs are monthly basis 5,900 yen. range of education and research facilities. Schools in collaboration with institutional facilities such as The room has the bathroom and the kitchen, and the As of May 2010, there were 9,328 students and 976 the attached schools. members of the teaching staff. Academic exchange kitchen furnishes the electromagnetic cooker and the refrigerator. Moreover, the room is offered with the air agreements have been drawn up with 97 universities/ 2. Number of students to be accepted : 5 institutions in 22 countries (Australia, People’s Republic of conditioner, the bed, the table, and the chair. -

Utsunomiya University Utsunomiya University's Motto

国立大学法人 AN INTRODUCTION TO Utsunomiya University Utsunomiya University's Motto “A wealth of ideas to the community and new knowledge to the world” The expansive University campuses are situated in a natural setting abounding in greenery. There are restaurants, a shopping mall, a cinema complex and other amenities located nearby. Students can live comfortably and enjoy themselves while studying at the University. Location Utsunomiya University is located approximately 100 kilometers north of Tokyo in the city of Utsunomiya, the prefectural capital of Tochigi. The traveling time to Tokyo is about 50 minutes by high-speed Shinkansen train and 80 minutes by ordinary train. It takes approximately three hours to reach Narita Airport by expressway limousine bus. The Tokyo Sky Tree broadcasting tower, soaring to a height of 634 meters and completed in the spring of 2012, is approximately two hours away by train on the Tobu Utsunomiya Line. Notable sites near Utsunomiya that always attract many tourists include Nikko, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Kinugawa Hot Springs and the Nasu vacationing area. Contents Introduction Campus Map Message from the President .............................................3 Mine Campus ...................................................... 21 The University’s Mission and Vision.................................4 Yoto Campus Branch.......................................... 22 What’s the Reason Why Utsunomiya University is so Delicious!? ...5 International Exchange......................................................6 -

Optical Design & Testing Short Course Program

OPTICAL DESIGN & TESTING SHORT COURSE PROGRAM OFFERED BY www.optics.arizona.edu/tokyo-short-course www.short-course.org August 1~3, 2017 Itabashi Green Hall Itabashi Culture Hall Itabashi, Tokyo, Japan SHORT COURSE FORMAT & DESCRIPTION The University of Arizona and Utsunomiya University is pleased to present our fifth series of Optical Science and Engineering short courses in Japan. Courses will be jointly taught by professors from the University of Arizona, College of Optical Sciences in the United States of America as well as from Utsunomiya University, Center of Optical Research and Education. Course contents are taken from our undergraduate and graduate courses in optics. Five courses will be taught in Japanese and the remainder in English. All classes will have Japanese speaking teaching assistants present to enable questions and discussions in Japanese. Students can learn geometrical optics, basic aberration theory, and its application to optical design, higher order aberration theory and its application lens design, illumination engineering, and basic and advanced physical optics including crystal optics, Fourier optics, OCT, polarization measurement, interferometric measurement. The lectures include total of 80 minutes (four of 20 minutes) of Q&A sessions as well as a reception on the first day. Students can effectively take advantage of these opportunities by a bi-directional and one-on-one interaction with instructors. In addition to providing high quality lectures with state-of-the-art contents, the short course program is a great opportunity to establish a long lasting tie among students and instructors at University of Arizona and Utsunomiya University, which will be a great asset for all the attendees. -

Fundamentals and Materials Society, the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan

Fundamentals and Materials Society, The Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan Board of Society Hiroshi Sakuma, Utsunomiya University President, Takatoshi Shindo, Central Research Institute of Naoyuki Aikawa, Tokyo University of Science Electric Power Industry Masahiro Tanaka, Gifu University Vice-President, Masayuki Hikita, Kyushu Institute of Technology Mitsuaki Maeyama, Saitama University Vice-President, Kinya Kobayashi, Hitachi, Ltd. Ken Kawamata, Tohoku Gakuin University Planning and General Affairs, Toshiya Tanaka, VISCAS Corporation Jun Hasegawa, Tokyo Institute of Technology Planning and General Affairs, Keizo Kato, Niigata University Naohiko Shimura, Toshiba Corporation Treasurer, Takao Tsurimoto, Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Takeshi Kinoshita, Keio University Treasurer, Yoshihiko Hirano, Toshiba Corporation Ken Imaike, Nihon University Editorial Affairs, Toshiki Nakano, National Defense Academy Masaaki Ikeda, Japan Nuclear Energy Safety Organization Editorial Affairs, Takashi Ikehata, Ibaraki University Satoru Kuboya, Toshiba Corporation R&D Management, Kazuo Adachi, Central Research Institute of Masaki Sekino, The University of Tokyo Electric Power Industry Toshiyuki Sawa, Hitachi, Ltd. R&D Management, Nobuhiro Matsushita, Tokyo Institute of Secretary, Akiko Kumada, The University of Tokyo Technology Secretary, Hiroaki Miyake, Tokyo City University Auditor, Yasushi Takemura, Yokohama National University 23 members Auditor, Toshiro Sato, Shinshu University Kazushi Ishiyama, Tohoku University Editorial Board Haruo Ihori,