PROKOFIEV Alexander Nevsky - Lieutenant Kijé Suite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: the Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator

1 History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: The Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator In May 1937, Sergei Eisenstein was offered the opportunity to make a feature film on one of two figures from Russian history, the folk hero Ivan Susanin (d. 1613) or the mediaeval ruler Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263). He opted for Nevsky. Permission for Eisenstein to proceed with the new project ultimately came from within the Kremlin, with the support of Joseph Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator was something of a cinephile, and he often intervened in Soviet film affairs. This high-level authorisation meant that the USSR’s most renowned filmmaker would have the opportunity to complete his first feature in some eight years, if he could get it through Stalinist Russia’s censorship apparatus. For his part, Eisenstein was prepared to retreat into history for his newest film topic. Movies on contemporary affairs often fell victim to Soviet censors, as Eisenstein had learned all too well a few months earlier when his collectivisation film, Bezhin Meadow (1937), was banned. But because relatively little was known about Nevsky’s life, Eisenstein told a colleague: “Nobody can 1 2 find fault with me. Whatever I do, the historians and the so-called ‘consultants’ [i.e. censors] won’t be able to argue with me”.i What was known about Alexander Nevsky was a mixture of history and legend, but the historical memory that was most relevant to the modern situation was Alexander’s legacy as a diplomat and military leader, defending a key western sector of mediaeval Russia from foreign foes. -

Stéphane Denève, Conductor Yefim Bronfman, Piano Clémentine

Stéphane Denève, conductor Friday, February 15, 2019 at 8:00pm Yefim Bronfman, piano Saturday, February 16, 2019 at 8:00pm Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director PROKOFIEV Cinderella Suite (compiled by Stéphane Denève) (1940-1944) (1891-1953) Introduction Pas-de-chale Interrupted Departure Clock Scene - The Prince’s Variation Cinderella’s Arrival at the Ball - Grand Waltz Promenade - The Prince’s First Galop - The Father Amoroso - Cinderella’s Departure for the Ball - Midnight PROKOFIEV Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, op. 16 (1913) Andantino; Allegretto; Tempo I Scherzo: Vivace Intermezzo: Allegro moderato Finale: Allegro tempestoso Yefim Bronfman, piano INTERMISSION 23 PROKOFIEV Alexander Nevsky, op. 78 (1938) Russia under the Mongolian Yoke Song about Alexander Nevsky The Crusaders in Pskov Arise, ye Russian People The Battle on the Ice The Field of the Dead Alexander’s Entry into Pskov Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2018/2019 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology and The Steward Family Foundation. Stéphane Denève is the Linda and Paul Lee Guest Artist. Yefim Bronfman is the Carolyn and Jay Henges Guest Artist. The concert of Friday, February 15, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Sally S. Levy. The concert of Saturday, February 16, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Ms. Jo Ann Taylor Kindle. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation. -

17 Infidel Turks and Schismatic Russians in Late Medieval Livonia

Madis Maasing 17 Infidel Turks and Schismatic Russians in Late Medieval Livonia 17.1 Introduction At the beginning of the sixteenth century, political rhetoric in Livonia was shaped by the threat posed by an alien power: Following a significant deterio- ration in the relations between the Catholic Livonian territories and their mighty Eastern Orthodox neighbour – the Grand Duchy of Moscow – war broke out, lasting from 1501 to 1503, with renewed armed conflict remaining an immi- nent threat until 1509. During this period of confrontation, and afterwards, the Livonians (i.e., the political elite of Livonia) fulminated in their political writ- ings about the gruesome, schismatic, and even infidel Russians, who posed a threat not only to Livonia, but to Western Christendom in general. In the Holy Roman Empire and at the Roman Curia, these allegations were quite favoura- bly received. Arguably, the Livonians’ greatest success took the form of a papal provision for two financially profitable anti-Russian indulgence campaigns (1503–1510). For various political reasons, the motif of a permanent and general ‘Russian threat’ had ongoing currency in Livonia up until the Livonian War (1558–1583). Even after the collapse of the Livonian territories, the Russian threat motif continued to be quite effectively used by other adversaries of Mos- cow – e.g., Poland-Lithuania and Sweden. I will focus here first and foremost on what was behind the initial success of the Russian threat motif in Livonia, but I will also address why it persisted for as long as it did. A large part of its success was the fact that it drew upon a similar phenomenon – the ‘Turkish threat’,1 which played a significant role in the political rhetoric of Early Modern Europe, especially in south-eastern 1 This research was supported by the Estonian Research Council’s PUT 107 programme, “Me- dieval Livonia: European Periphery and its Centres (Twelfth–Sixteenth Centuries)”, and by the European Social Fund’s Doctoral Studies and Internationalization Programme DoRa, which is carried out by Foundation Archimedes. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

Classical 5: Russia Was the Center of Much Revolution in the 20Th Century

Classical 5: Russia was the center of much revolution in the 20th century. Inventive and dramatic music of Shostakovich and Prokofiev capture the cultural spirit of the time. Dmitri Shostakovich (September 12/25, 1906-August 9, 1975) Symphony No. 5 in D minor, op. 47 (1937) Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, into a politically liberal family, Shostakovich was a child prodigy as a pianist and composer. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13, and by the time he graduated in 1926, Shostakovich was intent pursuing a dual career as a pianist and composer, but early success with his First Symphony led him to concentrate on composition. The premiere of his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1934 was a resounding success with critics and the public, and placed him at the forefront of Soviet musical composition. This also made him a target. Two years later, amid Stalin’s Great Terror, an article entitled “Muddle instead of music” took Shostakovich to task for producing “leftist confusion instead of natural, human music,” and warned him of the consequences of not changing his style to something more appropriate. The general public caught completely by surprise, and the composer was well aware that the consequences included the threat of death. His musical response was calculated carefully as he searched for the right balance between the directives for music that promoted the right sorts of emotional responses, accomplished by using overt lyricism and heroic textures, and his artistic desires for forward-looking styles. Much was at stake at the premiere of the Fifth Symphony on November 21, 1937. -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

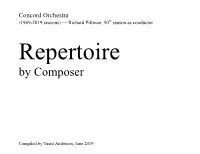

Orchestra Repertoire by Composer

Concord Orchestra (1969-2019 seasons) –– Richard Pittman, 50th season as conductor by Composer Compiled by Grant Anderson, June 2019 1 Concord Orchestra Repertoire by Composer (1969-2019 seasons) — Richard Pittman, conductor Composer Composition Composed Soloists Groups Concert Adams John (1947 – ) Nixon in China: The Chairman Dances 1985 May 2000 Adams John (1947 – ) ShortA Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 1990 Great Woods) Adams John (1947 – ) AShort Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 2000 Great Woods) Adler Samuel (1928 – ) TheFlames Flames of Freedom: Ma’oz Tzur (Rock 1982 Lexington High School December 2015 of Ages), Mi y’mallel (Who Can Retell?) Women’s Chorus (Jason Iannuzzi) Albéniz Isaac (1860 – 1909) Suite española, Op. 47: Granada & Sevilla 1886 May 2016 Albert Stephen (1941 – 1992) River-Run: Rain Music, River's End 1984 October 1986 Alford, born Kenneth, born (1881 – 1945) Colonel Bogey March 1914 May 1994 Ricketts Frederick Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 July 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 2003 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2007 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2011 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954 Norman Plummer, April 1971 Thomas Taylor, Stanley Schultz trumpet Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954f John Ossi, James May 1979 Dolham, -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts. -

Science and Pseudo-Science in Modern Studies of Aleksandr Nevskii

Вестник СПбГУ. История. 2017. Т. 62. Вып. 1 R. A. Sokolov SCIENCE AND PSEUDO-SCIENCE IN MODERN STUDIES OF ALEKSANDR NEVSKII The article provides insight into debates about the life and political activities of Aleksandr Nevskii and the historical memory of him which have been going on for the last year or two. The author focuses on arguments used by the scholars in this polemics and analyzes the attempts to cast doubt on the results of research which has already been conducted. The author recognizes the necessity to take into con- sideration the opinions of these scholars who have suggested new interpretations of the sources on the basis of scientifically tested methodology, hence drawing conclusions about the discreditable facts in the biography of the prince and the inefficiency of his policy in general (G. Fennell, D. N. Danilevskii). However, particular emphasis is placed on the insufficient account of the existing historiographic work as well as the methodically inappropriate use (and sometimes disregard) of the above-mentioned sources. This drawback is typical of the works of the authors whose insight into the issues they study is not deep enough and who, nonetheless, are given an opportunity to express their views in leading his- torical periodicals. These aspects allow us to determine the development of a tendency to neglect the works of our historical forbearers — Soviet and Russian historians. As an example, the article provides the analysis of the theoretical construct A. N. Nesterenko’s article, published in “Voprosy Istorii” (№ 1, 2016) and containing a number of hypotheses that remain unconfirmed by the facts to a consider- able extent. -

95.3 FM 6:45 Pm HARVARD MEN’S HOCKEY WHRB Program Guide Harvard at Princeton

N N December 2014 January/February 2015 Volume 43, No. 2 Winter Orgy® Period N 95.3 FM 6:45 pm HARVARD MEN’S HOCKEY WHRB Program Guide Harvard at Princeton. 10:00 pm VAPORWAVE ORGY Winter Orgy® Period, December, 2014 Vaporwave, an electronic genre that emerged early in this decade, in cyberspace, is often characterized by heavy with highlights for January and February, 2015 sampling and effect processing of 80’s lounge and smooth jazz. Consumerism and techno-corporatism is Vaporwave when it is Wednesday, December 2 one with mirroring ocean and Zen on a pseudo-neo Windows 95 screen. Often heard by Twitter users who used to collect 6:45 pm HARVARD WOMEN’S HOCKEY Digimon cards, the evolving underground genre reflects the Harvard vs. Dartmouth. nostalgia of the forever young. Macintosh Plus, Blank Banshee, PrismCorp Virtual Enterprises, and many others. Wednesday, December 3 Saturday, December 6 6:45 pm MEN’S BASKETBALL Harvard vs. Northeastern. 5:00 am THE FLIGHT OF THE CONDOR: 10:00 pm THE ONLY MAN THAT MATTERS MUSIC OF THE ANDES ORGY Ian MacKaye co-founded Dischord Records in 1980 at age The indigenous peoples of the Andes Mountains produced a 18 to release an album by his band The Teen Idles. Since 1980, style of music that is hauntingly beautiful, and lies in the grand MacKaye has transformed the punk-rock music scene through tradition of protest music along with punk, hip-hop, and outlaw his artistry and management of Dischord. His bands Minor country. After the Spanish conquest of South America, Andean Threat and Fugazi have gained critical acclaim in the hardcore folk music became a way of preserving an indigenous identity in and post-hardcore scenes respectively. -

Travels with an Opera: Prokofiev's War and Peace

Travels with an opera: Prokofiev’s War and Peace This is the story of two musical journeys: the road travelled by Prokofiev’s late operatic masterpiece, from its initial composition in 1941/2 to the first performance of that original version – scheduled for 22 January 2010; and the present writer’s forty-year journey away from, and then back to, the Russian composer and his operas. My association with the music of Sergei Prokofiev began in 1966, when I had to choose a subject for my doctoral research at the University of Cambridge. I wanted to work on twentieth-century opera: Alban Berg was my first choice, but someone else (the musicologist Douglas Jarman) was already working on him. Martinu? Hindemith? – not really. Prokofiev? - now there was a composer about whose orchestral music I had mixed views, whose piano music I found fascinating but singularly awkward to play, and about whose operas I knew absolutely nothing. Zilch. Hasty research revealed that I was not alone: the March and Scherzo from Love for Three Oranges apart, Prokofiev’s operatic repertoire was largely unknown and certainly unstudied in Western Europe. It seemed an excellent choice; though it was not long before I discovered that there were clear, if not good, reasons for both of these facts. Throughout his life Prokofiev was captivated by opera as a medium: he wrote his first operatic work – The Giant – at the age of nine; and a fortnight before his death he was still trying to find the perfect middle section for Kutuzov’s grandiose aria in War and Peace. -

Background Book 1 L E V Y & C a M P a I G N S E R I E S – V O L U M E I

Nevsky — Background Book 1 L EVY & C AMPAIGN S ERIE S – V O L UME I Teutons and Rus in Collision 1240-1242 by Volko Ruhnke by Pavel Tatarnikau BACKGROUND BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Nevsky – Some Play Hints ............................................. 2 The Teutons and Their Allies ..................................... 21 Solitaire Nevsky .............................................................. 3 The Russians and Their Allies .................................... 26 Examples of Play ........................................................... 3 Timeline ......................................................................... 24 Setup ........................................................................... 3 Arts of War ..................................................................... 31 Levy ............................................................................ 3 Teutonic Events .......................................................... 31 March, Feed, Sail........................................................ 7 Teutonic Capabilities .................................................. 34 Supply and Forage ...................................................... 10 Russian Events ........................................................... 38 Battle ......................................................................... 11 Russian Capabilities ................................................... 41 Siege and Storm ......................................................... 15 Design Note ..................................................................