Triangle Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

All-Celluloid Homage to a Diva of the Italian Cinema

ALL-CELLULOID HOMAGE TO A DIVA OF THE ITALIAN CINEMA Sept. 24, 2016 / Castro Theatre / San Francisco / CinemaItaliaSF.com ROMA CITTÀ APERTA (ROME OPEN CITY) Sat. September 24, 2016 1:00 PM 35mm Film Projection (100 mins. 1945. BW. Italy. In Italian, German, and Latin with English subtitles) Winner of the 1946 Festival de Cannes Grand Prize, Rome Open City was Roberto Rossel- lini’s revelation – a harrowing drama about the Nazi occupation of Rome and the brave few who struggled against it. Told with melodramatic flair and starring Aldo Fabrizi as a priest helping the partisan cause and Anna Magnani in her breakthrough role as Pina, the fiancée of a resistance member, Rome Open City is a shockingly authentic experi- ence, conceived and directed amid the ruin of World War II, with immediacy in every frame. Marking a watershed moment in Italian cinema, this galvanic work garnered awards around the globe and left the beginnings of a new film movement in its wake. Directed by Roberto Rossellini. Written by Sergio Amidei and Federico Fellini. Photo- graphed by Ubaldo Arata. Starring Anna Magnani and Aldo Fabrizi. Print Source: Istituto Luce-Cinecittá S.r.L. BELLISSIMA Sat. September 24, 2016 3:00 PM 35mm Film Projection (115 mins. 1951. BW. Italy. In Italian with English subtitles) Bellissima centers on a working-class mother in Rome, Maddalena (Anna Magnani), who drags her daughter (Tina Apicella) to Cinecittà to attend an audition for a new film by Alessandro Blasetti. Maddalena is a stage mother who loves movies and whose efforts to promote her daughter grow increasingly frenzied. -

Film Lives Heresm

TITANUS Two Women BERTRAND BONELLO NEW YORK AFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL MARTÍN REJTMAN TITANUS OPEN ROADS: NEW ITALIAN CINEMA HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL NEW YORK ASIAN FILM FESTIVAL SPECIAL PROGRAMS NEW RELEASES EMBASSY / THE KOBAL COLLECTION / THE KOBAL EMBASSY MAY/JUN 2015SM FILM LIVES HERE Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center 144 W 65th St | Walter Reade Theater 165 W 65th St | filmlinc.com | @filmlinc HERE STARTS PROGRAMMING SPOTLIGHT TABLE OF CONTENTS I PUT A SPELL ON YOU: THE FILMS OF BERTRAND BONELLO Festivals & Series 2 I Put a Spell on You: The Films of Bertrand Bonello (Through May 4) 2 PROVOKES PROVOKES Each new Bertrand Bonello film is an event in and of itself.Part of what makes Bonello’s work so thrilling is that, with some exceptions, world cinema has yet to catch up with his New York African Film Festival (May 6 – 12) 4 unique combination of artistic rigor and ability to distill emotion from the often extravagantly Sounds Like Music: The Films of Martín Rejtman (May 13 – 19) 7 stylish, almost baroque figures, places, and events that he portrays. He already occupies Titanus (May 22 – 31) 8 HERE FILM a singular place in French cinema, and we’re excited that our audiences now have the Open Roads: New Italian Cinema (June 4 – 11) 12 opportunity to discover a body of work that is unlike any other. –Dennis Lim, Director of Programming Human Rights Watch Film Festval (June 12 – 20) 16 New York Asian Film Festival (June 26 – July 8) 17 HERE FILM Special Programs 18 INSPIRES TITANUS Sound + Vision Live (May 28, June 25) 18 We have selected 23 cinematic gems from the Locarno Film Festival’s tribute to Titanus. -

Italy Lorenzo Codelli

).4%2.!4)/.!,ĺ&),-ĺ'5)$%ĺĺITALY | 207 )TALYĺ,ORENZOĺ#ODELLI IDĺ.ANNIĺ-ORETTIlSĺANTI "ERLUSCONIĺ THEĺüLMĺINDUSTRYĺ"ERNARDOĺ"ERTOLUCCI ĺONEĺ SATIRE ĺ4HEĺ#AIMANĺ)LĺCAIMANO ĺ OFĺTHEĺGROUPlSĺLEADERS ĺWROTEĺAĺPASSIONATEĺ $RELEASEDĺJUSTĺBEFOREĺTHEĺELECTIONSĺINĺ OPENĺLETTERĺTOĺ,Aĺ2EPUBBLICAĺLAMENTINGĺHOWĺ -AYĺ ĺCONVINCEĺANYĺOFĺTHOSEĺ ĺVOTERSĺ )TALIANĺNATIONALĺHERITAGEĺITSELFĺISĺINĺDANGERĺ pĺAĺNARROWĺMARGINĺpĺWHOĺDETERMINEDĺTHEĺFALLĺ #ULTUREĺ-INISTERĺ&RANCESCOĺ2UTELLIĺREACTEDĺ OFĺ3ILVIOĺ"ERLUSCONIlSĺRIGHT WINGĺGOVERNMENTĺ BYĺPROMISINGĺINCREASEDĺüNANCIALĺRESOURCES ĺ ANDĺTHEĺVICTORYĺOFĺ2OMANOĺ0RODIlSĺCENTRE LEFTĺ TAXĺSHELTERSĺANDĺOTHERĺREMEDIESĺ4OOĺLATEĺANDĺ COALITIONĺ4HEĺ#AIMANlSĺSUCCESSĺWASĺSOĺüERCEĺ NOTĺENOUGH ĺRESPONDEDĺANGRYĺüLMMAKERS ĺTOĺ THATĺEVENĺ"ERLUSCONI OWNEDĺCINEMAĺCHAINSĺ REVIVEĺPRODUCTIONĺANDĺDISTRIBUTIONĺONĺASĺLARGEĺAĺ WANTEDĺTOĺSCREENĺIT ĺBUTĺ-ORETTIĺREPLIED ĺk.O ĺ SCALEĺASĺISĺNEEDEDĺ THANKSlĺ(ISĺüLMĺHUMOROUSLYĺDESCRIBESĺBOTHĺ THEĺIMPOSSIBILITYĺOFĺPORTRAYINGĺSUCHĺANĺALMIGHTYĺ )TALYlSĺANNUALĺOUTPUTĺOFĺAPPROXIMATELYĺEIGHTYĺ MANIPULATOR ĺANDĺHOWĺAĺWHOLEĺCOUNTRYĺHASĺ üLMSĺREMAINSĺSCANDALOUSLYĺDIVIDEDĺINTOĺTWOĺ DETERIORATEDĺUNDERĺHISĺLEADERSHIPĺ&EDERICOĺ ECHELONSĺATĺONEĺEND ĺAĺDOZENĺGUARANTEEDĺ &ELLINIĺWOULDĺHAVEĺBEENĺVERYĺPROUDĺOFĺ-ORETTI ĺ BLOCKBUSTERS ĺWIDELYĺRELEASEDĺFORĺ#HRISTMAS ĺ HAVINGĺLANDEDĺTHEĺüRSTĺBLOWĺINĺĺWITHĺ %ASTER ĺORĺTHEĺEARLYĺ.OVEMBERĺHOLIDAYSĺATĺTHEĺ 'INGERĺANDĺ&RED OTHER ĺALLĺTHEĺREMAININGĺüLMS ĺPARSIMONIOUSLYĺ SCREENEDĺFORĺELITEĺAUDIENCES ĺORĺTHROUGHĺ FESTIVALS ĺLATE NIGHTĺ46ĺANDĺ$6$ĺRELEASES )TĺISĺMAINLYĺTHEĺFESTIVALS -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

Suso Cecchi D'amico

Suso Cecchi D'Amico Suso Cecchi D'Amico Nombre Giovanna Cecchi 21 de julio de 1914 Nacimiento Italia, Roma 31 de julio de 2010, 96 años Fallecimiento Italia, Roma Nacionalidad italiana Ocupación guionista, escritora Cónyuge Fedele D'Amico Hijos Silvia, Masolino y Caterina Padres Leonetta Pieraccini y Emilio Cecchi Suso Cecchi d'Amico (Giovanna Cecchi) (Roma, 21 de julio de 1914 – Roma, 31 de julio de 2010)1 , fue una de las más famosas guionistas del cine italiano, especialmente por sus guiones para Luchino Visconti, Vittorio De Sica, Franco Zeffirelli, Mario Monicelli y otros realizadores del neorrealismo italiano. Era conocida como La Reina de Cinecittà. Biografía Hija del escritor y guionista Emilio Cecchi (1884-1966) y de la pintora Leonetta Pieraccini, perteneció a la alta burguesía intelectual romana de principios de siglo. Su padre la llamó "Suso" (sobrenombre de Susana en dialecto toscano). Cursó estudios en el Liceo Francés y durante la guerra debió refugiarse en una granja de la familia cercana a Florencia por sus convicciones antifascistas que la llevaron a unirse a la resistencia. Fue la guionista de más de cien largometrajes entre 1946 y 2006. Sus más relevantes trabajos fueron con Roberto Rossellini (Roma, ciudad abierta), Vittorio de Sica (Ladri di biciclette, Milagro en Milán), Luchino Visconti (El gatopardo, Senso, Rocco y sus hermanos, Bellissima, El extranjero, Ludwig, El inocente, Nosotras las mujeres (quinto episodio con Anna Magnani), Mario Monicelli (Casanova '70), Franco Zeffirelli (La fierecilla domada; Hermano sol, hermana luna, Jesús de Nazaret), Mauro Bolognini (Metello), y otros. Fue condecorada con la Orden al Mérito de la República Italiana y en 1994 se le concedió el León de Oro del Festival de Venecia en honor a su trayectoria. -

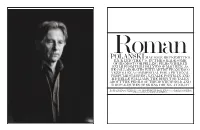

Polanskimay Soon Be Permitted Back Into the U.S., but He's Made Some of His Most Compelling Films While in Exile from the Holl

RomanMAY SOON BE PERMITTED POLANSKI BACK INTO THE U.S., BUT HE’S MADE SOME OF HIS MOST COMPELLING FILMS WHILE IN EXILE FROM THE HOLLYWOOD MACHINE. AS HE COLLABORATES WITH ARTIST FRANCESCO VEZZOLI ON A COMMERCIAL FOR A FICTIONAL PERFUME STARRING NATALIE PORTMAN AND MICHELLE WILLIAMS, THE DIRECTOR TALKS ABOUT THE PERILS OF THE MOVIE WORLD AND THE PLEASURES OF SKIING DRUNK AT NIGHT By FRANCESCO VEZZOLI and CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN Portrait PAOLO ROVERSI OPPOSITE: ROMAN POLANSKI, PHOTOGRAPHED IN PARIS ON NOVEMBER 25, 2008. YOU KNOW WHAT I like TO SEE AGAIN and AGAIN? SNOW WHITE. I DON’T THINK they MAKE ABOVE AND OPPOSITE: PHOTOS FROM THE SET OF GREED, THE NEW FRAGRANCE BY FRANCESCO VEZZOLI (2008), DIRECTED BY ROMAN POLANSKI ANYTHING better. IT’S so NAÏVELY BEAUTIFUL. AND STARRING MICHELLE WILLIAMS AND NATALIE PORTMAN. COSTUMES DESIGNED BY MIUCCIA PRADA. “ ” When Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli went look- Not like in America. [pauses] You know, I did an in- RP: No, I didn’t. But you have to take it into consid- ing for a director to help him make his latest art- terview for Interview with Andy back in 1973. eration, nevertheless. work, he went straight for the biggest. Vezzoli’s CB: I think, in fact, you did two with him. Do you FV: I’m sure you know the movie by [François] productions have always served up larger-than-life remember the questions he asked you? Truffaut called The Man Who Loved Women [1977]. spectacles studded with Hollywood mythos and RP: Not at all. He didn’t care. -

1 Revisiting the Past As a Means of Validation: Bridging the Myth of The

1 Revisiting the Past as a Means of Validation: Bridging the Myth of the Resistance and the Satire of the Economic Miracle in Two Comedies “Italian style” Giacomo Boitani, National University of Ireland, Galway Abstract: Many commedia all’italiana filmmakers have acknowledged the neorealist mode of production as a source of inspiration for their practice of pursuing social criticism in realistic and satirical comedies between 1958 and 1977. The detractors of the genre, however, have accused the commedia filmmakers of “diluting” the neorealist engagement to a simple description of the habits of Italians during the Economic Miracle, a description which threatened to encourage, through the casting of popular stars, the cynical attitude it sought to satirise. In this article, I shall discuss how two commedia all’italiana directors, namely Dino Risi and Ettore Scola, produced two significant commedie, respectively Una vita difficile (1961) and C’eravamo tanto amati (1974), which bridged the Resistance setting, associated with neorealism, and the Economic Miracle setting of most commedie all’italiana in order to reaffirm their neorealist roots, thus revisiting the past as a response to the critical underestimation from which their cinematic practice suffered. Many filmmakers of the comedy “Italian style” genre (commedia all’italiana) have acknowledged Italian neorealism as a source of inspiration for their practice of pursuing social criticism in realistic and satirical comedies produced in the years between 1958 and 1977. For instance, comedy “Italian style” star Alberto Sordi said that of those involved in the genre that “our project was to reinvent neorealism and to take it in a satirical direction” (Giacovelli, Un italiano 110),1 while director Marco Ferreri stated that “the commedia is neorealism revisited and modified in order to make people go to the movies” (Giacovelli, Commedia 21). -

Join Us. 100% Sirena Quality Taste 100% Pole & Line

melbourne february 8–22 march 1–15 playing with cinémathèque marcello contradiction: the indomitable MELBOURNE CINÉMATHÈQUE 2017 SCREENINGS mastroianni, isabelle huppert Wednesdays from 7pm at ACMI Federation Square, Melbourne screenings 20th-century February 8 February 15 February 22 March 1 March 8 March 15 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm Presented by the Melbourne Cinémathèque man WHITE NIGHTS DIVORCE ITALIAN STYLE A SPECIAL DAY LOULOU THE LACEMAKER EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Luchino Visconti (1957) Pietro Germi (1961) Ettore Scola (1977) Maurice Pialat (1980) Claude Goretta (1977) Jean-Luc Godard (1980) Curated by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. 97 mins Unclassified 15+ 105 mins Unclassified 15+* 106 mins M 101 mins M 107 mins M 87 mins Unclassified 18+ Supported by Screen Australia and Film Victoria. Across a five-decade career, Marcello Visconti’s neo-realist influences are The New York Times hailed Germi Scola’s sepia-toned masterwork “For an actress there is no greater gift This work of fearless, self-exculpating Ostensibly a love story, but also a Hailed as his “second first film” after MINI MEMBERSHIP Mastroianni (1924–1996) maintained combined with a dreamlike visual as a master of farce for this tale remains one of the few Italian films than having a camera in front of you.” semi-autobiography is one of Pialat’s character study focusing on behaviour a series of collaborative video works Admission to 3 consecutive nights: a position as one of European cinema’s poetry in this poignant tale of longing of an elegant Sicilian nobleman to truly reckon with pre-World War Isabelle Huppert (1953–) is one of the most painful and revealing films. -

ELENCO DEI FILM DISPONIBILI in BIBLIOTECA Aggiornato a Settembre 2019 a BEAUTIFUL MIND, Ron Howard, 2001 – Film Sul Matematico John Nash, Interpretato Da R

ELENCO DEI FILM DISPONIBILI IN BIBLIOTECA Aggiornato a settembre 2019 A BEAUTIFUL MIND, Ron Howard, 2001 – film sul matematico John Nash, interpretato da R. Crowe ABOUT A BOY, P & C. Weitz, 2002 – tratto dal romanzo di Nick Hornby, con Hugh Grant ABUNA MESSIAS, Goffredo Alessandrini, 1939 – film drammatico sulla presenza fascista in Etiopia ACROSS THE UNIVERSE, Julie Taymor, 2007 – film musicale con le canzoni dei Beatles A GERMAN LIFE, Christian Krönes, 2016 – docufilm con intervista alla segretaria di Goebbels A HARD DAY’S NIGHT, Richard Lester, 1964 – film su e con i Beatles ALEXANDER, Oliver Stone, 2004 – film con C. Farrell e A. Jolie sulla vita di Alessandro Magno ALÌ, Michael Mann, 2001 – film su 10 anni della vita del pugile Muhammad Alì, interpretato da W. Smith ALLA LUCE DEL SOLE, Roberto Faenza, 2005 – film sull’impegno antimafia di Don Pino Puglisi ALTA FEDELTÀ, Stephen Frears, 2000 – una storia di musica e amori tratta dal romanzo di N. Hornby AMADEUS, Milos Forman, 1984 – celebre film di Milos Forman sulla vita di W.A. Mozart AMARCORD, Federico Fellini, 1973 – uno dei capolavori del maestro del cinema italiano AMEN., Costa-Gavras, 2002 – film intenso sul controverso rapporto tra nazismo e Vaticano AMERICAN GANSTER, Ridley Scott, 2007 – film sulla vita del narcotrafficante Frank Lucas AMLETO, Claudio Fino, 1955 – l’opera di Shakeaspeare interpretata da Vittorio Gassman ANDIAMO A QUEL PAESE, Ficarra e Picone, 2014 – commedia comica ANGELI D’ACCIAIO, Katja Von Garnier, 2004 – la conquista del diritto di voto alle donne negli USA ANNA DEI MIRACOLI, Arthur Penn, 1962 – classico ispirato alla storia della sordo-cieca Helen Keller ARANCIA MECCANICA, Stanley Kubrick, 1971 – film su violenza giovanile e condizionamento del pensiero. -

The Grande Dame of Italian Cinema Published on Iitaly.Org (

The Grande Dame of Italian Cinema Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) The Grande Dame of Italian Cinema Benedetta Grasso (December 20, 2010) The talented and beloved screenwriter Suso Cecchi D'Amico remembered at the Casa Italiana Zerilli- Marimò. A documentary, a round table and a screening of Big Deal On Madonna Street, one of Mario Monicelli's masterpieces. Also announced - by Antonio Monda and Davide Azzolini - an event in January during the visit of the Cardinal of Naples Crescenzio Sepe in New York: Casa Italiana will host a conversation between the Cardinal and John Turturro about the representation of Naples in films. Stay tuned Think of some of the most famous Italian movies like The Leopard, Bycicle Thieves, Rocco and his Brothers, Big Deal on Madonna Street. Think of the setting, the character, the emotions, the historical relevance, the directors…You’ll probably be pretty familiar with them, you might recognize those scenes or at least a poster and perhaps you associate them with the image of Italy you hold in Page 1 of 3 The Grande Dame of Italian Cinema Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) your heart… But do you know whose hand was actually behind those scripts? Who put those words in the characters’ mouth and influenced immensely Italian cinema? The answer is: a highly educated, passionate and witty lady named Suso Cecchi D’amico (born Giovanna Cecchi, 1914-2010). For her screenwriting was a living, a job, but especially a craft. A pragmatic one. It wasn’t about claiming her authorship. -

Italian Cinema

THE CINEMA OF THE ITALIAN ECONOMIC MIRACLE BCSP - Fall 2021 Prof. Andrea Ricci (Indiana University) [email protected] HOURS: Tuesday 5 – 7pm Thursday 5 – 7pm Screenings: Thursday 7pm approx. BCSP classroom DESCRIPTION: This course aims to offer a broad view of the Italian cinema in its historical passage from the widely recognized Neorealist foundations to the great divide of the revolutionary Sixties, the culmination of its golden age. The modernization of Italian society, political changes, urbanization and the question of Italian identity, as reflected in the cinema of the 1960s, are the main topics of the course. All of the films covered in this course explore crucial moments in the history of modern Italian society from various sociopolitical points of view. The writers and directors depict through diverse cinematic styles encounters between cultures, religions, social classes and genders. The films lend themselves to enriching discussions about aesthetics, the evolution of Italian cinema, the influence on and comparison with cinema of other countries, and to cultural analysis of national identity, religion, ethnicity, gender and generational roles. Lessons Screenings (approx. 7-9pm) Tuesday, October 12 Introduction to the course. Italian history after WWII and important dates. Italian identity. 1 Introduction to concepts, such as: realismo, realtà, verismo, verità, verosimiglianza. Contradictory concepts in cinema: Melies vs. Lumiere. ====================================== =================================== Thursday, October 14 Thursday, October 14 Italian neorealism: departure or continuity? The Roberto Rossellini: Roma città aperta (1945) 2 three directors: Rossellini – De Sica – Visconti. Three interpretations of an historical moment. Gramsci’s legacy confirmed by national culture. ====================================== =================================== Tuesday, October 19 Quiz on the readings. Discussion on the films.