The Quantity Surveyor: Missing in Action in the USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property & Construction Cost Guide

AFRICA PROPERTY & CONSTRUCTION COST GUIDE 2020 2021 Africa Property & Construction Cost Guide 2020/2021 AECOM AECOM AFRICA PROPERTY & CONSTRUCTION COST GUIDE 2020/21 31st EDITION © 2020/21 ISBN: 978-1-990978-28-9 © AECOM SA (Pty) Limited. All rights reserved. Africa Property & Construction Cost Guide 2020/2021 AECOM Let’s get connected Follow @aecom on social media: Twitter https://twitter.com/AECOMBuildPlace Facebook https://www.facebook.com/AecomTechnologyCorporation LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/aecom Instagram https://www.instagram.com/aecom/ Get our Without Limits app To learn more about how AECOM is delivering a better world go to: www.aecom.com. Africa Property & Construction Cost Guide 2020/2021 AECOM Imagine it. Delivered. It’s one thing to imagine a better world. It’s another to deliver it. AECOM was built to do just that. With a deep and experienced global team, we design and deliver infrastructure and services that unlock opportunities for clients and communities, as well as protecting our environment and improving people’s lives. From urban centres to remote villages, our work is transformative. We make a positive and lasting impact by applying our global reach, connected expertise and delivery excellence to solve complex and evolving challenges. By providing clean water for developing communities, iconic skyscrapers that swell a nation’s pride, power and security to fuel economic prosperity, transportation that brings people together and thoughtful planning that sustains cities and natural resources - the difference that we help our clients make is felt in every region of the world. Our clients face tough and interrelated challenges that can only be solved by a company like ours. -

Civil Engineering Quantities

Civil Engineering Quantities A By the same author: Building Quantities Explained Civil Engineering Specification Municipal Engineering Practice Planned Expansion of Country Towns Civil Engineering Quantities by IVOR H. SEELEY B.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., C.Eng., F.R.I.C.S., F.I.Mun.E., F.I.Q.S., A.I.O.B. Chartered Quantity Surveyor and Chartered Engineer Head of Department of Surveying Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham S.I. EDITION Macmillan Education ISBN 978-1-349-01514-6 ISBN 978-1-349-01512-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-01512-2 © Ivor H. Seeley, 1965 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 2nd edition 1965 978-0-333-13577-8 First published 1965 Reprinted 1968 S.l. Edition 1971 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York, Toronto, Dublin, Melbourne, Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 135776 Preface THIS BOOK IS concerned with the measurement of all types of civil and municipal engineering work, in accordance with the principles laid down in the Standard Method of Measurement of Civil Engineering Quantities, and contains many worked examples covering all classes of work. The book is specially designed to meet the needs of students studying for the examinations of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (Quantity Surveying Section), the Institute of Quantity Surveyors, The Council of Engineering Institutions, the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Institution of Municipal Engineers, the Institution of Structural Engineers, the Building Surveyors' Institute and the Institute of Building and also for those proceeding to degrees, higher national certificates and diplomas in civil engineering, building and quantity surveying. -

The Surveying Profession in the United Kingdom

Keynote Address The Surveying Profession in the United Kingdom INTRODUC~ON veying" first appeared in English and was described T IS A VERY GREAT PRIVILEGE to be at this Opening as relakg mainly to the ''management" of land and I ceremonyofyour 50th convention, bringing to- buildings. But before I turn to the profession his- gether as it does two of your long-established profes- torically, let me put into context the ~oyal~nstitu- sional societies to consider the immense subject em- tion of Chartered Surveyors (RICS)and its relevance braced by your theme, "Technology in Transition." When I was invited to present this paper I was In the UK, professional interests in the fields of not aware that that would be the theme, and at first surveying and mapping are primarily (but not ex- sight the relevance of how the surveying profession clusively) represented by the RICS,which is the only is organized in the United Kingdom may not be such body incorporated by Royal Charter. apparent. Indeed, this becomes even more ques- A Royal Charter is granted by the Sovereign and tionable in view of this audience being primarily confers on the incorporated body extensive powers concerned with surveying and mapping and related of self-regulation, including (a) determination of sciences whereas in the UK the profession of sur- standards for entry to the profession, (b) holding veying has a much broader base. qualifying examinations and accepting university It is, however, relevant that the way in which that degrees in lieu, (c) prescribing a code of conduct broader base evolved can be traced to a beginning and exercising disciplinary powers, and (d) pro- in an earlier era of transition in technology, the in- viding services for the profession. -

Mr.Garreth Norman Bsc, Quantity Surveyor Senior Quantity Surveyor

Mr.Garreth Norman BSc, Quantity Surveyor Senior Quantity Surveyor OFFICE MOBILE +44 (0)7399 245 068 st OFFICE +44 (0)20 3696 7996 1 Floor, 2 Castle Yard, UK Tel 0800 319 6161 Richmond, Surrey, TW10 6TF [email protected] envistaforensics.com PROFILE Garreth Norman is an experienced quantity surveyor and employer’s agent/ project manager with over twenty years’ experience in quantity surveying and contract administration duties. Garreth has experience in both pre and post contract administration on a wide variety of engineering, building and process projects. Garreth has worked for both private and public sector clients on different projects carrying out a range of duties including due diligence, tender / contract preparation and administration, providing contractual advise, cost planning and estimating, quantum measurement, tender evaluation, interim valuations, final account preparation, rating and claims assessments, risk identification analysis, costing and value engineering appraisals. Garreth has worked within project teams on numerous projects including retail, residential (private and social), industrial, education, healthcare and defense estates schemes including building refurbishments. Has provided contractual advice under various forms of contract including NEC, ICE, JCT and various bespoke forms of contract. For the last 10 years Garreth has worked on insurance losses as part of the Insurance Services Team with Mouchel and then McLellan & Partners. This work has included carrying out post-loss damage surveys and the provision of quantum and cost assessments for Property Damage. Reviewing the Insured’s proposed reinstatement budgets, purchase orders, tenders and reinstatement programmes; Reviewing potential reinstatement works programmes to the insured’s own programmes; as well as identifying potential risks and mitigation strategy assisting when required with specific input on Contents and Business Interruption matters to support the Loss Adjusters at meetings with the Insured and other Insurers/Re-Insurers. -

Weekend Property & Construction News

Weekend Property & Construction News Weekend 14 / 15 January 2006 Circulation : exceeds 3,000 subscribers Property and Construction related articles featured on the Internet during the past week brought to you by ASAQS. Editor: Bert van den Heever News specific to the quantity surveying profession is reflected at the bottom of this newsletter. Click on the blue headline if you wish to read the full article on the Internet. Past issues of this newsletter can be found at http://www.asaqs.co.za/news/property_news.html Quantity Surveying News Construction and Development ASAQS NEWS News Retail Roundup MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF ASAQS, MR EGON WORTMANN Newsflashes for Architects Project Management News On behalf on the Board of the Association of South African Quantity Surveyors, we Engineering News would like to wish all our members and colleagues compliments of the season and News for Estate Agents and everything of the best for the year 2006. Home Owners Latest property news As the festive season is now a thing of the past, it is time for the construction industry To subscribe to the Twiice newsletter Business Incentives to once again take up the cudgels and prepare for the challenges that lie ahead "Design Despatches" News from Africa during the coming year. General indications are that we can look forward to a busy please click here. Mining News year and we look forward with anticipation to the exciting challenges that lie ahead. The Agent's tool kit May you all have a wonderful year and above all, a profitable one. Building Terms Weekly Economic Indicators COMBINED PRESIDENTIAL / VICE PRESIDENTIAL TOUR 2006 Key Economic Indicators Free Contracts During the Association Board meeting held during October 2005, it was agreed that the Presidential and Tailpiece Vice Presidential Tours 2006 to the respective Chapters will be combined into one tour this year. -

Construction

CONSTRUCTION STACKABLE CREDENTIALS: Utah’s construction industry will need about 95,000 new employees from 2016–2019. Cur- rent worker shortages are being reported in nearly all trades. 5 Construction workers can “earn while they learn” through apprenticeship programs or on-the-job training. Certified or PH.D. OR credentialed journeyman status can be achieved in one year MASTER’S for some trades and up to six years for others with little or no DEGREE debt. Construction wages range from $45,000–$85,000 per 4 DEVELOPMENT year. Benefits include health insurance, retirement programs, POSITIONS and additional training. Construction workers can begin at an BACHELOR’S entry-level position and climb the corporate ladder. DEGREE Not Required MANAGEMENT 3 POSITIONS Business ASSOCIATE Development DEGREE Director Chief Financial Applied Officer Associate Degree 2 or Associate Communications Degree Director CREDENTIAL Human Resource Apprenticeship, Comptroller Director Journeyman, Construction Marketing Director Certificate, or Manager Project Engineer 1 License Estimator Project Executive Carpenter Human Resource Project Manager HIGH SCHOOL Professional DIPLOMA/GED Electrician Project Labor Relations Superintendent Brick Mason Heavy Equipment Specialist Operator Safety Director Carpenter Project Assistant Pipe Fitter Cement Mason Safety Professional Plumber Electrician’s Helper Project Foreman Heavy Equipment Truck Driver Operator Welder Insulator CAREER ADVANCEMENT Iron Worker Laborer (All Trades) CAREER DEVELOPMENT Plumber’s Helper SKILL SET ENHANCEMENT Truck Driver ENTRY-LEVEL EMPLOYMENT HANDS-ON ANALYTICAL Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, UT 84114-4200 Sydnee Dickson, State Superintendent of Public Instruction ENGINEERING STACKABLE CREDENTIALS: In a very basic sense, engi- neers use math and science to solve world problems. -

Quantity Surveying As a Profession Introduction

QUANTITY SURVEYING AS A PROFESSION INTRODUCTION This write-up contains information on education and practice of Quantity Surveying. It is prepared to guide Students in Secondary Schools who are often faced with the challenge of choosing a career. It will therefore help those of them who are interested to know and understand the basic requirements in choosing Quantity Surveying as a profession. QUANTITY SURVEYING PROFESSION A Quantity Surveyor is a professional working within the Building and Engineering Construction Industry that is concerned with cost and contract administration from conception to close out stage. The Building & Engineering Construction Industry; Building Construction – Residential Housing Estate High rise buildings School Classroom Blocks Shopping malls Hospitals Engineering Construction - Civil Engineering (Roads & Bridges, Railways , Dams etc) Industrial Engineering(Power Plants, Refineries, Steel Mills, Telecommunication etc) THE QUANTITY SURVEYOR A Quantity Surveyor (Q/S) is a Development and Construction Cost Adviser on Building, Civil, and Industrial Engineering Projects. The Quantity Surveyor is the Financial Expert in all matters relating to Building, Civil, and other Engineering Projects. The Quantity Surveyor is often referred to as a Cost Consultant, Technical Accountant or Cost Engineer of the Construction Industry. DUTIES OF THE QUANTITY SURVEYOR The duties of a Quantity Surveyor include the followings: i. Carrying out feasibility studies of capital projects. ii. Preliminary Cost advice which entails preparation of Cost Estimates, Budgets, Cost Planning, Cost Checks and Cost Control . iii. Tender/Contract Documentation which includes preparation of Bills of Quantities and other Tender documents, giving advice on Tendering/Bidding procedures, Contractual arrangement and Tender Evaluation and Analysis. DUTIES OF THE QUANTITY SURVEYOR CONT’D iv. -

Section 5 – Term of Reference (TOR) Contents 1 INTRODUCTION

Annex I: Section 5 – Term of Reference (TOR) Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background to the Project .............................................................................. 3 1.2 The Project ..................................................................................................... 3 2 SCOPE OF SERVICES ......................................................................................... 5 2.1 General ........................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Scope of Services .......................................................................................... 5 2.3 Typical Tasks .................................................................................................. 5 2.4 Types of Projects ............................................................................................ 6 2.5 List of Engineering Requirements .................................................................. 7 3 PROJECT PHASES .............................................................................................. 7 Task 1: Data Collection and Records Documentation ............................ 8 Task 2: Collect Data, Review and Analysis ............................................. 8 Task 3: Interviews with Local Authorities and Other Stakeholders ......... 8 Task 4: Field Verification of Collected Data ............................................ 9 Task 5: Surveying -

The Challenges of Quantifying Construction Works for Project Control in Ghana

3134 CIB World Building Congress 2007 CIB2007-348 The Challenges of Quantifying Construction Works for Project Control in Ghana Gabriel Nani1 and Theophilus Adjei-Kumi2 1 and 2 Building Technology Department, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi ABSTRACT Project control is undertaken throughout a construction process and it involves planning, monitoring, comparing actual with planned and taking actions. The three major areas of control in construction are ‘cost control’, ‘Quality control’ and ‘Schedule or progress control’. In all planning/ setting target and monitoring, work quantity information is used within the control mechanism to provide vital information. The paper therefore identifies the challenges of accurately quantifying construction work and organising the quantified information for control processes in Ghana. A structured questionnaire was administered to Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers on phone (not a common research practice in Ghana) to rate pre-identified challenges quantity surveyor face in quantification of construction work. Poor quality of drawings, limited time to carryout measurement, lack of adequate quantification skills, poor specification, poor remuneration, difficulty in interpretation of standard method of measurement, and difficulty in measuring work on site in that order were identified as the major challenges to quantification in Ghana. The major impact of these challenges is on cost control of project which is vital to developing countries. Keywords: Quantification, Challenges, Project, Control 1. INTRODUCTION Quantities of construction work are used for several purposes in construction. Pickens and Jaggar (2005) who are Quantity Surveyors described ‘measurement (quantification) as ‘a process concerned with converting construction drawings into words and numbers in accordance CIB World Building Congress 2007 3135 with a strict set of rules. -

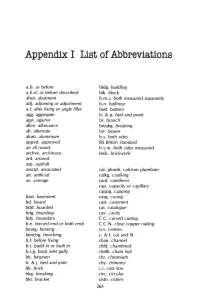

Appendix I List of Abbreviations

Appendix I List of Abbreviations a.b. as before bldg. building a.b.d. as before described blk. block abut. abutment b.m.s. both measured separately adj. adjoining or adjustment b.n. bullnose a.f. after fixing or angle fillet bott. bottom agg. aggregate b. & p. bed and point agst. against br. branch alice. allowance breakg. breaking alt. alternate brr. bearer alum. aluminium b.s. both sides appvd. approved BS British Standard air all round b.s.m. both sides measured archve. architrave bwk. brickwork ard. around asp. asphalt assctd. associated cal. plumb. calcium plumbate art. artificial calkg. caulking av. average cant. cantilever cap. capacity or capillary cappg. capping bast. basement casg. casing bd. board cast. casement bdd. boarded cat. catalogue bdg. boarding cav. cavity bdy. boundary C.C. curved cutting b.e. bossed end or both ends C.C.N. close copper nailing bearg. bearing ccs. centres benchg. benching c. & f. cut and fit b. f. before fixing chan. channel b.i. build in or built in chfd. chamfered b.i.g. back inlet gully chnlk. chain link bit. bitumen chr. chromium b. & j. bed and joint chy. chimney bk. brick c. i. cast iron bkg. breaking eire. circular bkt. bracket cistn. cistern 263 264 Building Quantities Explained c.j. close jointed dia. or diam. diameter clg. ceiling diag. diagonally cln. clean diagrm. diagram else bdd. close boarded diff. difference c. m. cement mortar dimnsd. dimensioned col. colour disch. discharge comb. combined dist. distance or distemper comm. commencing ditto. or do. that which comms. commons has been said before commsng. -

Quantity Surveying Role in Construction Projects -A Comparison of Roles in Sweden and the UK

Quantity surveying role in Construction Projects -a comparison of roles in Sweden and the UK Examensarbete VT 2011 Rabie Maarouf Byggdesign Riad Habib Byggdesign Handledare: Anders Peterson Sammanfattning Varje projekt är unik och beroende av flera aktö rer och leverantö rer som normalt varierar frå n projekt till projekt. Fö r att en byggentreprenö r skall vara framgå ngsrik och konkurrenskraftig så är det viktigt att leverera projektet i tid, inom budget och med hö g kvalitet. Vå ra slutsatser och intervjuer i denna studie visar att korrekta ritningar, ö msesidigt fö rtroende och väl fungerande kommunikationer är viktiga faktorer fö r ett lyckat projekt. Byggindustrin är på väg mot ett utö kat samarbete. Personliga mö ten är fortfarande viktiga även om ny teknik fö renklar kunskapsutbytet. Därfö r bö r regelbundna mö ten mellan konsulter och underleverantö rer hå llas under hela designprocessen. Under flera decennier har diskussioner om hur man gö r byggbranschen mer effektivt drivit på utvecklingen av standarder och system. Det finns nu allt stö rre tryck på att infö ra nya produktionsfilosofier i konstruktionen fö r att uppmuntra hå llbara värden och minska den negativa effekten av arbetstiden i ett projekt. Det ö vergripande syftet med den här studien är att ö ka fö rstå elsen och fö rdjupa kunskaper om relationen mellan aktö rerna i byggprocessen och hur projektet är upphandlat fö r att bidra till bättre slutresultat fö r bå de beställare och entreprenö r. Vi har fö rsö kt markera betydelsen av ”quantity surveying” och dessutom att jämfö ra roll skillnaden allmänt mellan Sverige och Storbritannien. -

What Is a Prqs

What is a PrQS A Professional quantity surveyor (PrQS) is a professional working within the construction and engineering industry concerned with building costs. The profession develop during the 19th century from the earlier "measurer", a specialist tradesman (often a guild member), who prepared standardised schedules for a building project in which all of the construction materials, labour activities and the like were quantified, and against which competing builders could submit priced tenders. The modern-day QS often reports to either Client, Project Manager, Principle Agent or Architect and provides advice in the decision-making process throughout the management of a project from initial inception to final completion. The QS handles estimating and cost control, the tendering process and, after contract award, the commercial interface. QSs should be able to carry out estimating and measurement of construction works prior to tender, producing the bill of quantities; produce tender documentation and manage the tender process; clarify and evaluate tenders; and manage the resultant contract through monthly valuations, variations control, contract administration and assessment of claims. As well as in professional quantity surveying practices, the QS finds employment in all parts of industry and government including primary and secondary industry, national and local government bodies and agencies, contractors and subcontractors, developers, and financial and legal companies. The functions of a consultant quantity surveyor : Professional Quantity Surveyor are broadly concerned with contracts, measurement and costs on construction projects. The methods employed, however, cover a range of activities which may include cost planning, value engineering, value management, feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis, life-cycle costing, risk analysis, tendering, valuation, change control, dispute resolution, claims management, project management, cost estimation and value for money assessments.