Aneurin Bevan and Paul Robeson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales Revised from a paper given to the Virgil Society on 18 May 2013 Davies Whenever I make the short journey from my home to Swansea’s railway station, I pass two shops which remind me of Virgil. Both are chemist shops, both belong to large retail empires. The name-boards above their doors proclaim that each shop is not only a “pharmacy” but also a fferyllfa, literally “Virgil’s place”. In bilingual Wales homage is paid to the greatest of poets every time we collect a prescription! The Welsh words for a chemist or pharmacist fferyllydd( ), for pharmaceutical science (fferylliaeth), for a retort (fferyllwydr) are – like fferyllfa,the chemist’s shop – all derived from Fferyll, a learned form of Virgil’s name regularly used by writers and poets of the Middle Ages in Wales.1 For example, the 14th-century Dafydd ap Gwilym, in one of his love poems, pic- tures his beloved as an enchantress and the silver harp that she is imagined playing as o ffyrf gelfyddyd Fferyll (“shaped by Virgil’s mighty art”).2 This is, of course, the Virgil “of popular legend”, as Comparetti describes him: the Virgil of the Neapolitan tales narrated by Gervase of Tilbury and Conrad of Querfurt, Virgil the magician and alchemist, whose literary roots may be in Ecl. 8, a fascinating counterfoil to the prophet of the Christian interpretation of Ecl. 4.3 Not that the role of magician and the role of prophet were so differentiated in the medieval mind as they might be today. -

New Perspectives on Modern Wales

New Perspectives on Modern Wales New Perspectives on Modern Wales: Studies in Welsh Language, Literature and Social Politics Edited by Sabine Asmus and Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup New Perspectives on Modern Wales: Studies in Welsh Language, Literature and Social Politics Edited by Sabine Asmus and Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup Reviewer: Prof. dr. Eduard Werner This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Sabine Asmus, Katarzyna Jaworska-Biskup and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2191-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2191-9 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................. 3 Welsh or British in Times of Trouble? Shaping Welsh Culture and Identity during the Second World War Martin Andrew Hanks CHAPTER TWO .......................................................................................... 31 Local or National? Gender, Place and Identity in Post-Devolution Wales’ Literature Rhiannon Heledd Williams CHAPTER THREE -

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee S4C Written evidence - web List of written evidence 1 URDD 3 2 Hugh Evans 5 3 Ron Jones 6 4 Dr Simon Brooks 14 5 The Writers Guild of Great Britain 18 6 Mabon ap Gwynfor 23 7 Welsh Language Board 28 8 Ofcom 34 9 Professor Thomas P O’Malley, Aberystwth University 60 10 Tinopolis 64 11 Institute of Welsh Affairs 69 12 NUJ Parliamentary Group 76 13 Plaim Cymru 77 14 Welsh Language Society 85 15 NUJ and Bectu 94 16 DCMS 98 17 PACT 103 18 TAC 113 19 BBC 126 20 Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture 132 21 Mr S.G. Jones 138 22 Alun Ffred Jones AM, Welsh Assembly Government 139 23 Celebrating Our Language 144 24 Peter Edwards and Huw Walters 146 2 Written evidence submitted by Urdd Gobaith Cymru In the opinion of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, Wales’ largest children and young people’s organisation with 50,000 members under the age of 25: • The provision of good-quality Welsh language programmes is fundamental to establishing a linguistic context for those who speak Welsh and who wish to learn it. • It is vital that this is funded to the necessary level. • A good partnership already exists between S4C and the Urdd, but the Urdd would be happy to co-operate and work with S4C to identify further opportunities for collaboration to offer opportunities for children and young people, thus developing new audiences. • We believe that decisions about the development of S4C should be made in Wales. -

Framing Welsh Identity Moya Jones

Framing Welsh identity Moya Jones To cite this version: Moya Jones. Framing Welsh identity. Textes & Contextes, Université de Bourgogne, Centre Interlangues TIL, 2008, Identités nationales, identités régionales, https://preo.u- bourgogne.fr/textesetcontextes/index.php?id=109. halshs-00317835v2 HAL Id: halshs-00317835 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00317835v2 Submitted on 8 Sep 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Article tiré de : Textes et Contextes. [Ressource électronique] / Centre de Recherche Interlangues « texte image langage ». N°1, « identités nationales, identités régionales ». (2008). ISSN : 1961-991X. Disponible sur internet : http://revuesshs.u-bourgogne.fr/textes&contextes/ Framing Welsh identity Moya Jones, UMR 5222 CNRS "Europe, Européanité, Européanisation ", UFR des Pays anglophones, Université Michel de Montaigne - Bordeaux 3, Domaine universitaire, 33607 Pessac Cedex, France, http://eee.aquitaine.cnrs.fr/accueil.htm, moya.jones [at] u-bordeaux3.fr Abstract Welsh Studies as a cross-disciplinary field is growing both in Wales and beyond. Historians, sociologists, political scientists and others are increasingly collaborating in their study of the evolution of Welsh identity. This concept which was for so long monopolised and marked by a strong reference to the Welsh language and the importance of having an ethnic Welsh identity is now giving way to a more inclusive notion of what it means to be Welsh. -

Plaid Cymru and the SNP in Government

What does it mean to be ‘normal’? Plaid Cymru and the SNP in Government Craig McAngus School of Government and Public Policy University of Strathclyde McCance Building 16 Richmond Street Glasgow G1 1QX [email protected] Paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association, Cardiff, 25 th -27 th March 2013 Abstract Autonomist parties have been described as having shifted from ‘niche to normal’. Governmental participation has further compounded this process and led to these parties facing the same ‘hard choices’ as other parties in government. However, the assumption that autonomist parties can now be described as ‘normal’ fails to address the residual ‘niche’ characteristics which will have an effect on the party’s governmental participation due to the existence of important ‘primary goals’. Taking a qualitative, comparative case study approach using semi-structured interview and documentary data, this paper will examine Plaid Cymru and the SNP in government. This paper argues that, although both parties can indeed be described as ‘normal’, the degree to which their ‘niche’ characteristics affect the interaction between policy, office and vote-seeking behaviour varies. Indeed, while the SNP were able to somewhat ‘detach’ their ‘primary goals’ from their government profile, Plaid Cymru’s ability to formulate an effective vote-seeking strategy was severely hampered by policy-seeking considerations. The paper concludes by suggesting that the ‘niche to normal’ framework requires two additional qualifications. Firstly, the idea that autonomist parties shift from ‘niche’ to ‘normal’ is too simplistic and that it is more helpful to examine how ‘niche’ characteristics interact with and affect ‘normal’ party status. -

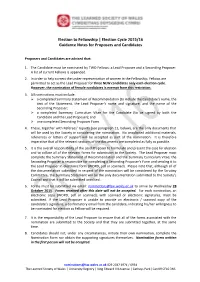

Election Cycle 2015/16 Guidance Notes for Proposers and Candidates

Election to Fellowship | Election Cycle 2015/16 Guidance Notes for Proposers and Candidates Proposers and Candidates are advised that: 1. The Candidate must be nominated by TWO Fellows: a Lead Proposer and a Seconding Proposer. A list of current Fellows is appended. 2. In order to help correct the under-representation of women in the Fellowship, Fellows are permitted to act as the Lead Proposer for three NEW candidates only each election cycle. However, the nomination of female candidates is exempt from this restriction. 3. All nominations must include: a completed Summary Statement of Recommendation (to include the Candidate’s name, the text of the Statement, the Lead Proposer’s name and signature, and the name of the Seconding Proposer; a completed Summary Curriculum Vitae for the Candidate (to be signed by both the Candidate and the Lead Proposer); and one completed Seconding Proposer Form. 4. These, together with Referees’ reports (see paragraph 12, below), are the only documents that will be used by the Society in considering the nomination. No unsolicited additional materials, references or letters of support will be accepted as part of the nomination. It is therefore imperative that all the relevant sections of the documents are completed as fully as possible. 5. It is the overall responsibility of the Lead Proposer to formulate and present the case for election and to collate all of the relevant forms for submission to the Society. The Lead Proposer must complete the Summary Statement of Recommendation and the Summary Curriculum Vitae; the Seconding Proposer is responsible for completing a Seconding Proposer’s Form and sending it to the Lead Proposer in electronic form (WORD, pdf or scanned). -

Finding Aid - 'Have a Cigarette' by Saunders Lewis (NLW MS 23867D.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - 'Have a Cigarette' by Saunders Lewis (NLW MS 23867D.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 13, 2017 Printed: May 13, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/have-cigarette-by-saunders-lewis archives.library .wales/index.php/have-cigarette-by-saunders-lewis Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk 'Have a Cigarette' by Saunders Lewis Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points .............................................................................................................. -

Rob Phillips the WELSH POLITICAL ARCHIVE at the NATIONAL LIBRARY of WALES

Rob Phillips THE WELSH POLITICAL ARCHIVE AT THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF WALES Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru or The National Library of Wales (NLW) in Aberystwyth was established in 1909, to collect and provide access to the documentary history of the nation. It is a legal deposit library and is therefore entitled to receive a copy of all books, magazines, newspapers etc. published in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The Welsh Political Archive (WPA) is a dedicated programme within the Library, established in 1983, to collect, catalogue and promote archival material which reflects the political life of Wales. There is one staff member who coordinates the WPA’s activities, answers enquiries, promotes the archive and works to attract archives to add to the collection. Organising and cataloguing archives is undertaken by staff in the NLW’s Archives and Manuscripts Section. But as the political collections include tapes of radio and television programmes, photographs, works of art, electronic files and websites, the WPA works across departments within the National Library. In addition to curatorial work, the Welsh Political Archive also works to promote the use of the political collections through lectures and exhibitions. An advisory committee (comprised of representatives of political parties and civil society, journalists and academics), guiding the work of the WPA, meets annually. Rob Phillips, ‘The Welsh Political Archive at the National Library of Wales’, in: Studies on National Movements, 3 (2015). http://snm.nise.eu/index.php/studies/article/view/0310s Studies on National Movements, 3 (2015) | SOURCES Collections Many of the political archives the NLW holds are personal collections of well-known political figures (Members of Parliament, Lords, Members of the European Parliament and Assembly Members); the formal records of a large number of political organisations – including the main political parties, campaign groups, referendum campaigns – and business and labour groups constitute another important part. -

Wales: the Heart of the Debate?

www.iwa.org.uk | Winter 2014/15 | No. 53 | £4.95 Wales: The heart of the debate? In the rush to appease Scottish and English public opinion will Wales’ voice be heard? + Gwyneth Lewis | Dai Smith | Helen Molyneux | Mark Drakeford | Rachel Trezise | Calvin Jones | Roger Scully | Gillian Clarke | Dylan Moore | The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • Acuity Legal • Age Cymru • BBC Cymru Wales • Arriva Trains Wales • Alcohol Concern Cymru • Cardiff County Council • Association of Chartered • Cartrefi Cymru • Cardiff School of Management Certified Accountants (ACCA) • Cartrefi Cymunedol • Cardiff University Library • Beaufort Research Ltd Community Housing Cymru • Centre for Regeneration • Blake Morgan • Citizens Advice Cymru Excellence Wales (CREW) • BT • Community - the union for life • Estyn • Cadarn Consulting Ltd • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Glandwr Cymru - The Canal & • Constructing Excellence in Wales • Disability Wales River Trust in Wales • Deryn • Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru • Harvard College Library • Elan Valley Trust • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Heritage Lottery Fund • Eversheds LLP • Friends of the Earth Cymru • Higher Education Wales • FBA • Gofal • Law Commission for England and Wales • Grayling • Institute Of Chartered Accountants • Literature Wales • Historix (R) Editions In England -

Annual Review 2010-11

QUALI AAWDURDODOL Gweledigaeth AAWDURDODOL QUALI ANNIBYNNOL THE LEARNED SOCIETY OF WALES CYMDEITHAS DDYSGEDIG CYMRU CELEBRATING SCHOLARSHIP AND SERVING THE NATION BENIGOL DATHLU YSGOLHEICTOD A GWASANAETHU’R GENEDL • YMCHWIL • YSGOLHEICTOD Review • RHAGORIAETH 2010/11 • AWDURDODOL • AUTHOR 2010/11 • EXCELLENC Adolygiad SCHOLARSHIP • • RESEARCH CELEBRATING SCHOLARSHIP AND SERVING THE NATION THE SERVING AND SCHOLARSHIP CELEBRATING EXPERT DATHLU YSGOLHEICTOD A GWASANAETHU’R GENEDL GWASANAETHU’R A YSGOLHEICTOD DATHLU THE LEARNED SOCIETY OF WALES OF SOCIETY LEARNED THE CYMDEITHAS DDYSGEDIG CYMRU DDYSGEDIG CYMDEITHAS INDEPENDENT QUALI AUTHORITATIVE VISION THE LEARNED SOCIETY OF WALES CYMDEITHAS DDYSGEDIG CYMRU CELEBRATING SCHOLARSHIP AND SERVING THE NATION DATHLU YSGOLHEICTOD A GWASANAETHU’R GENEDL Legal Advisers Morgan Cole Solicitors Park Place Cardiff CF10 3DP Auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP One Kingsway Cardiff CF10 3PW. Bankers HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited 97 Bute Street Cardiff Bay CF10 5PB Registered Address The University Registry King Edward VII Avenue Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NS Company Number 7256948 Registered Charity Number 1141526 For more information about the Society, contact: Dr Lynn Williams Chief Executive and Secretary The Learned Society of Wales PO Box 586 Cardiff CF11 1NU (29) 2037 6951 email: [email protected] or visit the Society’s website: http://learnedsocietywales.ac.uk The Learned Society of Wales Review 2010/11 1 President’s Introduction The Learned Society of Wales is Wales’s first The Society will also harness and channel national scholarly academy. Its establishment in May the nation’s talent for the good of our country. It 2010 marks a very important development in the will act as a defender of and protagonist for the intellectual and cultural life of our nation. -

North by Northeast Ken Skates Talks to Rhea Stevens

the welsh agenda North by Northeast Ken Skates talks to Rhea Stevens Grahame Davies, Hannah Blythyn, Llyr Gruffydd & Darren Millar on connecting North East Wales Exclusive Fiction: Dai Smith, Rachel Trezise, Rhian Elizabeth Plus • Gill Morgan on How Change Happens • Ruth Hussey on Health and Social Care • Philip Dixon on Successful Futures Winter 2017 | No. 59 | £4.95 www.iwa.wales Cover Photo: John Briggs The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Jane Hodge Foundation, the Welsh Books Council, the Friends Provident Foundation, and the Polden Puckham Charitable Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: • Aberystwyth University • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Public Services Ombudsman for Wales • Acuity Legal Limited • Ffilm Cymru • PwC • Alcohol Concern Cymru • Four Cymru • RenewableUK • Amgueddfa Cymru National • Friends of the Earth Cymru • RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects Museum Wales • Geldards LLP • Rondo Media • Association of Chartered Certified • Community - the union for life • Royal College of Nursing in Wales Accountants (ACCA) • Glandwr Cymru - The Canal & River • RSPB Cymru • Bangor University Trust in Wales • RWE Innogy UK • BBC Cymru Wales • Gofal • S4C • Blake Morgan • Goodson Thomas Ltd • Samaritans • British Council - Wales • Harvard College Library • Shelter Cymru • BT • Heritage Lottery Fund • Smart Energy GB • Cathedral School • Historix Editions • Snowdonia National Park Authority • Capital Law LLP • Hugh James • Sport Wales • Cardiff County