Economic Effect of Restricted Crossing U-Turn Intersections in Louisiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11.02

Chapter 11.02 DEFINITIONS1 Sections: 11.02.010 Interpretation. 11.02.015 AASHTO. 11.02.020 Acceptance. 11.02.030 All weather surface. 11.02.040 California Culvert Practice. 11.02.050 Consulting engineer. 11.02.060 Contractor. 11.02.070 County. 11.02.080 County engineer. 11.02.090 Department. 11.02.100 Director. 11.02.110 Driveway. 11.02.120 Driveway, common. 11.02.130 Final map. 11.02.140 May. 11.02.145 MUTCD. 11.02.150 Parcel map. 11.02.160 Road, Arterial. 11.02.170 Road, Collector. 11.02.180 Road, Cul-de-sac. 11.02.190 Road, Local. 11.02.200 Road, Through. 11.02.210 Road, Off-site. 11.02.220 Shall. 11.02.230 Special provisions. 11.02.240 Stabilometer “R” value. 11.02.250 State. 11.02.260 State specifications. 11.02.270 Traffic index. 11.02.280 Traveled way. 11.02.290 Turnaround bulb. 11.02.300 Turnaround, hammerhead. 11.02.310 Turnout. 11.02.320 Uniform surface. 11.02.330 Urban development. 11.02.340 Urban streets. 11.02.010 Interpretation. In this title or the state Highway Transportation Officials. (Ord. 3298 § 2, specifications, the intent and meaning of the terms 2016) that are used shall be as defined in Section I of the state specifications except as specifically noted, 11.02.020 Acceptance. “Acceptance” means the revised or added in this title. Except where formal written acceptance by the Director for work otherwise indicated, all specified or referenced which is completed on roads which are to be distances are measured along the ground. -

501 - Fire Apparatus Access Standard

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 83010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-388-8738 Fax: 805-388-4356 501 - FIRE APPARATUS ACCESS STANDARD The information contained in this standard is provided solely for the convenience of the reader and was being enforced by the Ventura County Fire Protection District at the time of its publication. The District reserves the right to make changes and improvements to this standard as and when required by law, or otherwise, at any time. The District’s current standards will be posted and made available for downloading by the public at the following web site: www.vcfd.org Please note that the District assumes no liability for any damages incurred directly or indirectly as a result of any errors, omissions, or discrepancies between this standard and any applicable law. It is the sole responsibility of the person or persons conducting any work pursuant to this standard to ensure their work complies with any and all applicable codes, ordinances, and regulations. Supersedes: VCFPD Standards 14.6.4, 14.6.5, 14.6.6, 14.6.7, 14.6.8, 14.6.9 and 14.6.11 CHAPTER 1 – ADMINISTRATION 1.1 Purpose. The purpose of this standard shall be to provide clarification of requirements and establish and assign an acceptable level of quality and minimum level of mandatory controls to provide and maintain required fire department access to premises in compliance with the Ventura County Fire Code. The provisions of this standard are general in nature and are not intended to over- ride the specific requirements of the Ventura County Fire Apparatus Access Code. -

MANUAL of UNIFORM MINIMUM STANDARDS for DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION and MAINTENANCE for STREETS and HIGHWAYS (Commonly Known As the &Qu

Topic # 625-000-015 MANUAL OF UNIFORM MINIMUM STANDARDS FOR DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE FOR STREETS AND HIGHWAYS (Commonly known as the "Florida Greenbook") State of Florida Department of Transportation MAY 2011 EDITION The Florida Greenbook will be posted on the FDOT Web Site at: http://www.dot.state.fl.us/rddesign/FloridaGreenbook/FGB.shtm USER REGISTRATION Manual of Uniform Minimum Standards for Design, Construction and Maintenance for Streets and Highways (Commonly known as the "Florida Greenbook") MAY – 2011 EDITION To: “Florida Greenbook” Users The Department of Transportation utilizes a contact database that enables the Department to e-mail important information to registered users on topics selected by each user. The database allows a user to update their physical address, e-mail address, topics of interest, and any other information in their profile at any time. All Florida Greenbook users must register their e-mail addresses in this contact database in order to receive updates, notices, design memos, or other important information concerning the Department's design manuals. Users must register at the following link: http://www2.dot.state.fl.us/contactmanagement/ New subscribers will need to create a new account. Once the information is registered, new subscribers will need to “Edit Interests.” The Florida Greenbook may be found under: Publications Design Roadway Design Florida Greenbook” Topic # 625-000-015 May - 2011 Manual of Uniform Minimum Standards for Design, Construction and Maintenance for Streets and Highways -

Flexibility in Highway Design

Flexibility in Highway Design U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Page i This page intentionally left blank. Page ii A Message from the Administrator Dear Colleague: One of the greatest challenges the highway community faces is providing safe, efficient transportation service that conserves, and even enhances the environmental, scenic, historic, and community resources that are so vital to our way of life. This guide will help you meet that challenge. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has been pleased to work with the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and other interested groups, including the Bicycle Federation of America, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and Scenic America, to develop this publication. It identifies and explains the opportunities, flexibilities, and constraints facing designers and design teams responsible for the development of transportation facilities. This guide does not attempt to create new standards. Rather, the guide builds on the flexibility in current laws and regulations to explore opportunities to use flexible design as a tool to help sustain important community interests without compromising safety. To do so, this guide stresses the need to identify and discuss those flexibilities and to continue breaking down barriers that sometimes make it difficult for highway designers to be aware of local concerns of interested organizations and citizens. The partnership formed to develop this guidance grew out of the design-related provisions of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 and the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995. Congress provided dramatic new flexibilities in funding, stressed the importance of preserving historic and scenic values, and provided for enhancing communities through transportation improvements. -

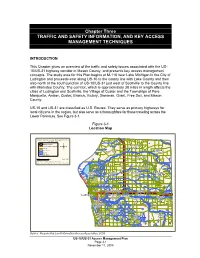

Chapter Three TRAFFIC and SAFETY INFORMATION, and KEY ACCESS MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES

Chapter Three TRAFFIC AND SAFETY INFORMATION, AND KEY ACCESS MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES INTRODUCTION This Chapter gives an overview of the traffic and safety issues associated with the US- 10/US-31 highway corridor in Mason County, and presents key access management concepts. The study area for this Plan begins at M-116 near Lake Michigan in the City of Ludington and proceeds east along US-10 to the county line with Lake County and then also north at the south junction of US-10/US-31 just west of Scottville to the County line with Manistee County. The corridor, which is approximately 38 miles in length affects the cities of Ludington and Scottville, the Village of Custer and the Townships of Pere Marquette, Amber, Custer, Branch, Victory, Sherman, Grant, Free Soil, and Mason County. US-10 and US-31 are classified as U.S. Routes. They serve as primary highways for local citizens in the region, but also serve as a thoroughfare for those traveling across the Lower Peninsula. See Figure 3-1. Figure 3-1 Location Map Mason County Access Management Plan US-10/US-31 Study Corridor U.S. & State Highway Free Soil Roads Twp Jurisdictions Meade Grant Twp Lakes Twp Streams Free Soil 01230.5 Mi les July 2005 Data Source: MCGI, Dept of Info Tech Map Prepared by Land Information Access Association 1 3 - S Fountain U Hamlin Victory Sherman Sheridan M Twp Twp Twp Twp - 1 1 6 US-10 US-10/US-31 US-10 1 Ludington 3 Amber Custer - Scottville Branch R Twp B Custer Twp Pere Twp Marquette Twp Riverton Twp Summit Eden Logan Twp Twp Twp US-31 Source: Prepared by Land Information Access Association, 2005 US-10/US-31 Access Management Plan Page 3-1 November 11, 2005 TRAFFIC AND SAFETY ANALYSIS Volumes According to 24 Hour AADT (average annual daily traffic) volumes for 2004 provided by the Michigan Department of Transportation and illustrated for all vehicles on Figure 3-2 and just for commercial vehicles on Figure 3-3. -

Chapter 2 Roads Board Transportation Committee March 26, 2019

Chapter 2 Roads Board Transportation Committee March 26, 2019 William Capers III Department of Transportation Chapter 2 Roads Background ❑ Named for the County Code chapter describing procedures for managing County-owned property ❑ County Code § 2-1-1: “dedicated to public use or title to which is in the name of the Board of Supervisors or the County” ❑ Typically are unimproved non-County maintained right-of-ways, that have not been accepted into the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Secondary System. ❑ Over 100 Chapter 2 roads in the County that have escrows, potentially many more without escrows. 2 Chapter 2 Roads (Continued) Background ❑ VDOT’s current policy is to not accept new roads in the Secondary System unless they have at least three unique users. ❑ When fewer than four users front a right-of-way, current County Code for each new user requires them to pay an escrow for future construction of a public road. ❑The fourth user of the right-of-way is responsible for constructing part of the public street, using the collected escrows, and providing the difference. ❑ Escrows are managed by Land Development Services ❑LDS also handles requests to build on Chapter 2 Roads. 3 Case Studies Case #1- Washington Street (Springfield District) Case #2- Lyles Road (Lee District) Washington Street Case #1: Washington Street (Springfield District) Braddock Road Section of Washington Street not in VDOT Secondary System Washington Street First First Rd Park Authority Property Washington Street was dedicated by a plat recorded on July 23, 1945 5 Case #1: Washington Street (Springfield District) 6 Nature of Inquiry ❑ No public road on this part of Washington Street. -

Improvements to FM 1560 and SH 16

FM 1560 & SH 16 Open House Public Meeting August 14, 2014 FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 FM 1560 RE-ALIGNMENT AT SH 16 & SH 16 SUPERSTREET CONCEPT . OPEN HOUSE PUBLIC MEETING Helotes City Hall . August 14, 2014 12951 Bandera Road . 5:00 p.m. – 7:00 p.m. Helotes, Texas 78023 FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 FM 1560 Project Location FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 3 Need and Purpose .Need –Current alignment of FM 1560 – SH 16 intersection restricts traffic flow, leading to traffic congestion .Purpose –Improve operational functioning and safety of FM 1560 - SH 16 intersection FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 4 Project Information .Project selected as part of the Alamo Area Metropolitan Planning Organization’s call for projects STP-MM (Cat 7 funds) .Project submitted by City of Helotes and TxDOT FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 5 Crash History LEGEND 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 6 Travel Patterns . FM 1560 to SH 16 NB – Turn south on SH 16 and U-Turn . Circle A Trail to SH 16 SB – Turn north on SH 16 and U-Turn . FM 1560 SB to Circle A Trail – U-Turn south of Circle A Trail FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 7 Typical Section Existing FM 1560 Generally Includes: . Two 12’ travel lanes (one in each direction) . 4’ striped median . Two 4’ outside shoulders . Open ditch FM 1560 Re-Alignment at SH 16 8 Typical Section Proposed FM 1560 Generally Includes: . Four 11’ travel lanes (two in each direction) . -

LAKE PONTCHARTRAIN CAUSEWAY HAER LA-21 and SOUTHERN TOLL PLAZA Causeway Boulevard Metairie Jefferson Parish Louisiana

LAKE PONTCHARTRAIN CAUSEWAY HAER LA-21 AND SOUTHERN TOLL PLAZA Causeway Boulevard Metairie Jefferson Parish Louisiana PHOTOGRAPHS COPIES OF COLOR TRANSPARENCIES WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD LAKE PONTCHARTRAIN CAUSEWAY AND SOUTHERN TOLL PLAZA HAER LA-21 Page 1 Location: The Lake Pontchartrain Causeway spans Lake Pontchartrain from Causeway Boulevard in Metairie, Jefferson Parish to Highway 190, Mandeville, St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. The southern Toll Plaza was located at the Jefferson Parish terminus of the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway. The Northern Terminus of the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway is located at 30.365 and -90.094167. The Southern Terminus is located at 30.02 and - 90.153889. This information was acquired using Google Earth imagery. There are no restrictions on the release of this information to the public. USGS Quadrangle maps (7.5 minute series): (north to south) Mandeville, Spanish Fort NE, West of Spanish Fort NE, Indian Beach There are no restrictions on this information. Owner: Greater New Orleans Expressway Commission Present Use: Vehicle Bridge Significance: When completed in 1956, the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway was the world’s longest bridge. This record was broken by completion of the parallel span in 1969. At 23.87 miles long, the Causeway is the world’s longest continuous span over water. The prestressed, pre-cast concrete structural system displays mid-twentieth century technology that typifies modern bridge construction techniques. In addition, the Causeway is significant in the development of the Jefferson and St. -

Roundabout Maintenance Manual Indiana LTAP

Indiana LTAP Roundabout Maintenance Manual Roundabout Maintenance Manual January 2015 INDIANA LTAP CENTER Purdue University Civil Engineering 3000 Kent Ave. Ste. C2-118 West Lafayette, Indiana 47906 Telephone: (765) 494-2164 Toll Free in Indiana: (800) 428-7639 Facsimile: (765) 496-1176 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................... 7 Section I: Winter Maintenance ........................................................................ 8 Snowplowing ......................................................................................................................................... 8 De-icing ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Equipment .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Section II: Summer Maintenance ................................................................... 10 Suggested Landscaping ..................................................................................................................... 10 Central Island Maintenance ............................................................................................................. 10 Splitter Island Maintenance ............................................................................................................ -

211 Limited Access Facilities

Topic #625-000-002 FDOT Design Manual January 1, 2018 211 Limited Access Facilities 211.1 General This chapter includes criteria for limited access facilities (tolled and non-tolled), including: (1) Interstates (2) Freeways (3) Expressways (4) Interchange ramps servicing high speed limited access facilities (5) Collector-distributor roads (C/D) servicing high speed limited access facilities Express lanes design is an iterative process best performed in a collaborative environment involving various disciplines e.g. express lanes planning, PD&E, construction, maintenance, traffic operations, transportation systems management and operations (TSM&O), and Turnpike toll operations. An explanation of the process and considerations is given in The Express Lanes Handbook Sections 6 and 8. Many design criteria are related to design speed; e.g., vertical and horizontal geometry, sight distance. When the minimum design values are not met, an approved Design Exception or Design Variation is required. See FDM 201.4 for information on Design Speed. See FDM 122 for information on Design Exceptions and Design Variations. The following manuals and documents provide additional information for the design of limited access facilities: General Tolling Requirements (GTR) -This document is used for design criteria and requirements for tolling on Turnpike and Non-Turnpike projects. This includes “open road” tolling facilities, express lanes (managed lanes, high occupancy tolling lanes, etc.) on new or existing corridors. A Policy on Design Standards – Interstate System, 2005 Edition (AASHTO) Turnpike Design Handbook (TDH) Express Lanes Handbook Traffic Engineering Manual (TEM) - This manual is used to supplement the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD)’s standards and guidelines with Florida specific signs and pavement markings used on the State Highway System by the Department’s Traffic Operations Offices. -

Persistently Improving Schools in Michigan Moving Past a History Of

RESEARCH PAPER Persistently Improving Schools in Michigan OCTOBER 2013 Moving Past a History of Low Performance American Institutes for Research and the University of Michigan, on Introduction behalf of the Michigan Department The challenges associated with the nation’s persistently low-achieving schools have of Education, conducted this study come to the policy forefront in the past five years. This policy focus was driven, in in 2012. We gratefully acknowledge part, by studies that revealed that schools identified for restructuring under the the contributions of principals, Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as reauthorized by the 2002 No teachers, and other respondents Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), lingered in this status for years, and administrators who took time out of their busy opted for the least-intensive interventions (Taylor, Stecher, O’Day, Naftel, & Le Floch, schedules to respond to our data 2010). In response, policymakers called for more dramatic action to compel these requests. We are also grateful for schools to break the cycle of low performance. the careful review by our colleagues Mette Huberman and Coby Meyers. The School Improvement Grants (SIG) program, funded through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (which provides $4 billion in funds for persistently low-achieving schools), has become emblematic of the federal focus on school turnaround. These SIG grants target the lowest 5 percent of schools, which must adopt one of four federal intervention models that include replacement of the principal, increased data use, extended learning time, and (in the case of one model) replacement of half of the teachers. A set of case studies of six persistently improving schools in Michigan revealed some common practices Kerstin Carlson Le Floch and dispositions: Diane Massell § A Culture of Caring. -

Roadway Design Manual (RDW)

Roadway Design Manual Revised July 2020 © 2020 by Texas Department of Transportation (512) 463-8630 all rights reserved Manual Notice 2020-1 From: Camille Thomason, P.E Manual: Roadway Design Manual Effective Date: July 01, 2020 Purpose The Roadway Design Manual has been revised to update roadway policy in accordance with FHWA guidelines and with comments received from Design Division, other Divisions, and TxDOT's 25 Districts. As a result, revisions were made to Chapters 1-8 and Appendices A, B and C. Also, new Appendices D, and E were added to the manual, that is, Right Turn Slip Lane Design Guidelines and Alternative Intersections and Interchanges, respectively. Likewise, minor errata type corrections and edits were made throughout the manual. Contents Chapter 1 Section 1: Revised Roadway Design Manual Format for chapters 7, 8, Appendix C, and to include the addition of Appendices D, and E. Under External Reference Documents, updated references. Section 2: Revised controlling criteria per FHWA guidance for Design Exceptions, Waivers, and Variances. Reduced controlling criteria from 13 to 10. Under Design Exceptions, added guidance that 4' minimum width is required for new bike lanes. Widths less than 4' will require a design exception. Under Design Exceptions, added guidance that design exceptions for bridge rails shall be sent to Bridge Division. Under Design Waivers, removed "non-controlling criteria for the" from introductory sentence. Under Design Waivers, removed requirement for copy of documentation being furnished to Design Division. Under Design Waivers, added "Shared Use Paths (if this is the chosen Bicycle/Ped facility)" to 4R. Under Special Facilities, moved sentence "Design waivers are not applicable…" to the bottom of the section.