Heritage Impact Assessment Boschendal Village Node

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Tulbagh As Cultural Signifier

BETWEEN MEMORY AND HISTORY: THE RESTORATION OF TULBAGH AS CULTURAL SIGNIFIER Town Cape of A 60-creditUniversity dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Conservation of the Built Environment. Jayson Augustyn-Clark (CLRJAS001) University of Cape Town / June 2017 Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ‘A measure of civilization’ Let us always remember that our historical buildings are not only big tourist attractions… more than just tradition…these buildings are a visible, tangible history. These buildings are an important indication of our level of civilisation and a convincing proof for a judgmental critical world - that for more than 300 years a structured and proper Western civilisation has flourished and exist here at the southern point of Africa. The visible tracks of our cultural heritage are our historic buildings…they are undoubtedly the deeds to the land we love and which God in his mercy gave to us. 1 2 Fig.1. Front cover – The reconstructed splendour of Church Street boasts seven gabled houses in a row along its western side. The author’s house (House 24, Tulbagh Country Guest House) is behind the tree (photo by Norman Collins). -

Boschendal Heritage Black Angus 2016 Tasting Sheet

This iconic wine estate and pride of the Cape is situated between Stellenbosch and Franschhoek. With over 333 years of winemaking heritage, 2017 marked the release of the pinnacle of Boschendal’s wine portfolio – the Boschendal Heritage Collection. To mark this auspicious event, the first two of three wines in this range of limited release, meticulously crafted red wines were made available to wine connoisseurs in 2017 - the Boschendal Grande Syrah 2014 and Black Angus 2014. Vintage: 2016 Cultivar: Shiraz 59%, Cab Sauv 25%, Merlot 11%, Malbec 5% Wine of Origin: Stellenbosch In the Vineyard: This interesting and captivating wine is Shiraz - based (59%), rounded off by Cabernet Sauvignon (25%), Merlot (11%) and Malbec (5%). This is the original ‘Estate Blend’ of Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon that Boschendal launched in the 1980’s under the Grand Reserve label. But our winemaking team has decided to add more complexity and intricacy in the blend with the addition of Merlot and Malbec for style and sophistication. Vinification: The grapes were harvested by hand and carefully sorted upon arrival at the cellar. All 4 varietals are vinified separately and after malolactic fermentation in stainless steel tanks, barrel maturation followed in a combination of new and older 300-litre barrels for 18 months. The wines were then blended and bottled in the new Boschendal Heritage bottle. Tasting Notes: This proprietary Shiraz-led blend takes its name from the bloodline of Black Angus cattle bred on Boschendal. The wine is full-bodied with black pepper and cherry flavours on the nose and a rich and complex palate. -

Champagne & Sparkling Wine White Wines

Champagne & Sparkling Wine These wines are produced in the method called Champenoise, where secondary fermentation takes place inside the bottle. These wines have a delicious biscuty character with a delicate sparkle. The wines tend to quite full bodied and will complement most dishes - delightful with fresh oysters as well as possibly the best combination with a decadent chocolate dessert. Bottle Glass Pongraz Stellenbosch 165 42 Bright, busy bubbles with Granny Smith flavours Graham Beck Brut Robertson 175 45 Stylish with Chardonnays lemon freshness and a gentle yeast overlay Graham Beck Rose Robertson 320 Beautiful, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay blend with strawberry flavours, fresh and a rich creamy complexity Moet & Chandon Brut Imperial N/V 350ml 355 Pale yellow with fresh fruit aromas, buttery and creamy notes Moet & Chandon Brut Imperial N/V 750ml 530 Pale yellow with fresh fruit aromas, buttery and creamy notes Veuve Clicquot Non Vintage Champagne 570 Blend of three Champagne grapes, combining body and elegance White Wines Chardonnay Possibly one of the most sought after white wines for the past two decades. The wines tend to be barrel matured to varying degrees, ranging from light delicate wines to powerful blockbuster wines. Delicate flavours of vanilla and citrus are the most stand out flavours, sometimes- tropical pineapple flavours can be found. Having a rounder, fuller mouth feel, they tends to be best partnered with white meat dishes with rich sauces but can be excellent with duck, Carpaccio or salmon. Indaba Stellenbosch 85 25 Medium bodied, with pear and pineapple aromas and a hint of butterscotch Brampton unoaked Stellenbosch 105 Rich, full flavoured and fruity, pear, peaches and ginger Durbanville Hills Durbanville 105 35 Soft and easy, with melon and lightly-buttered toast notes. -

New Classics the Beachhouse Bellingham Boschendal

NEW CLASSICS from the cape For almost 30 years now we’ve worked to introduce farm is one of South Africa’s original estates. From in the bottle. The wine must be great, but so must the the world-class wines of South Africa to the United Chardonnay to Cabernet to Pinot Noir to their how. I mention all of this as there is a quote on DGB’s States. It’s been an incredibly rewarding journey, as spectacular sparkling selections (Cap Classique)— website that has made me smile every time I see it: “we time and time again we’ve been able to show what these wines represent some of the best the country never forget to take care of the small details.” I love this great wine producing country can do while has to offer. We are extremely excited to have them that – it’s how we work as well. wowing our customers every step of the way. join the portfolio. It took just one glass of their Elgin We are also exceptionally proud to represent DGB’s Our hunt to deliver value—from everyday $10 Chardonnay to realize that Boschendal is going to be legacy as an incredibly inclusive wine company. For wines all the way up to our 100pt collectables—has a leader in an entire next generation’s love affair with decades DGB has been a leader in hiring, training and always guided us, as has finding independent, honest fine South African wine. developing a next generation of black winemakers. producers that respect the land and still make wine The Beach House has done something many brands Presently, their all-star Cap Classique winemaker based on the old-fashioned way. -

Sparkling White Wine Red Wine Cocktails

COCKTAILS WINE ZULU SPARKLING WHITE Hendrick’s Gin, Cucumber, Lemon, S&P 12 CHAMPAGNE SPARKLING SAUVIGNON BLANC Villa Sandi Prosecco Italy.................................................................10/35 Klein Constantia Constantia, SA........................................................12/45 LION’S HEAD Boschendal Brut Rosé Stellenbosch, SA....................................... 14/52 Neil Ellis “Amica” Jonkershoek, SA.....................................................15/55 Dickel Bourbon, Ginger Beer, Lime, Bitters Boschendal Brut Western Cape, SA.....................................................60 Rombauer Napa Valley, CA....................................................................15/55 13 Sparkle Horse Stellenbosch, SA......................................................20/60 OTHER WHITES/ROSÉ CAPE OF STORMS Paul Cluver Riesling Elgin, SA...............................................................12/45 Infused Pineapple Rum, Fresh Lime, Ginger Beer CHARDONNAY Ken Forrester Chenin Blanc Stellenbosch, SA..................................11/42 12 Sea Sun by Caymus Napa Valley, CA...............................................12/45 Robertson Gewurztraminer Elgin, SA................................................11/42 Robertson SA.........................................................................................12/45 Boschendal Chardonnay/Pinot Noir Stellenbosch, SA........................12/45 THE 10 Rustenburg Stellenbosch,. SA..........................................................15/55 Art of Earth -

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

Archaeological Assessment of Portions 7/1674 and 10/1674 of the Boschendal Estate

Archaeological Assessment of Portions 7/1674 And 10/1674 Of The Boschendal Estate. Report prepared for Sarah Winter on behalf of the proponent Boschendal March 2015 Prepared by Natalie Kendrick Tim Hart ACO associates CC 8 Jacobs Ladder St James 7945 Phone 021 7064104 1 Summary ACO Associates CC was appointed by Boschendal Estates, to undertake an archaeological assessment of a proposed development of the “New Village Boschendal”, on a section of the Boschendal estate. The proposed activity has triggered section 38.8 of the National Heritage Resources Act which requires the completion of an Archaeological Impact Assessment. The proponent wishes to construct mixed density residential housing and general business buildings, including retail. Sarah Winter is undertaking the Heritage Impact Assessment of which this report is a specialist component. The proposed development is situated on mixed land straddling Helshoogte Road (R310), and just off the R45 in Stellenbosch on portions 7/1674 and 10/1674. Currently the land contains some residential housing, orchards, unused land with uninhabited labourers cottages and a saw mill. Findings: The site is not archaeologically sensitive as it has been heavily transformed. No clear evidence of Early or Middle Stone age archaeological material was encountered, nor are there any buildings that require grading. Grading: Indications are that there are no finds worthy of grading in terms of HWC’s draft policy document on the grading of archaeological sites (in prep 2015). No mitigation is called for. There -

Wedding & Event Packages

WEDDING & EVENT PACKAGES 2021 - 2022 WELCOME TO BOSCHEDNAL Boschendal provides an idyllic and natural setting for any function or event. Surrounded by the breathtaking Groot Drakenstein and Simonsberg mountains you will find many function venues to choose from enabling you to tailor your special event. Boschendal is located in the centre of Franschhoek, Paarl and Stellenbosch. We are only 45 minutes drive from Cape Town City Centre and 40 minutes drive from Cape Town International Airport. Up to 180 guests can be accommodated across the farm in luxury cottages. All of our functions are catered in-house by Executive Chef, Allistaire Lawrence and his team. Our farm-to-table menus use only the best quality seasonal ingredients sourced from our fields, gardens and local like-minded suppliers. We raise our own award-winning Black Angus cattle, acorn-fed pigs, free-range chickens and harvest most of our vegetables from the organic Werf Food Garden. A SUMMARY OF OUR VENUES THE OLIVE PRESS RHONE HOMESTEAD MOUNTAIN VILLA THE RETREAT PRIVATE PICNICS 250 PAX 40 PAX 100 PAX 72 PAX 250 PAX Exposed natural poplar roof Our Cape Dutch historical Stunning six-bedroom villa at The natural surroundings Our two picnic areas are trusses, floor to ceiling glass Rhone Homestead with it’s the foot of the Simonsberg make it perfect for outdoor ideal for more casual, doors and stunning views over lush private gardens is perfect Mountain with views of the weddings or pre-wedding picnicstyle functions. We meadow gardens and Groot for small intimate events. entire Franschhoek Valley. festivities. have the Rhone Picnic area Drakenstein Mountains make Situated next to the Rhone Perfect for an intimate and the Werf Picnic area for a picturesque event. -

Thesis Sci 1992 Brink Yvonne.Pdf

PLACES OF DISCOURSE AND DIALOGUE: A STUDY IN THE MATERIAL CULTURE OF THE CAPE DURING THE RULE OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, 1652 - 1795. YVONNE BRINK August 1992. University of Cape Town Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town "Toon mij uw huis, en ik zal zeggen wie u bent". (Show me your house and I will tell you who you are - Old Dutch proverb). Dwelling: Vrymansfontein, Paarl ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I need to thank a number of people who, by means of a variety of gifts - film, photographs, various forms of work and expertise, time, and encou ragement - have made it possible for me to produce this thesis. They are: My husband, Bredell, and my children and their spouses - Hilde and Raymond, Andre and Lynnette, Bredell Jr. and Salome. My family has sup ported me consistently and understood my need to complete this research project. Bredell Jr.'s contribution was special: not only has he been my main pillar of support through all the hard work, but he taught me to use a word processor with great patience, and undertook the important job of printing the manuscript. -

Methode Cap Classique & Sparkling

Fine Dining Wine List Champagne, Proseco Methode Cap Classique & Sparkling Champagne Laurent-Perrier Brut Tours-Sur-Marne R926 Veuve Clicquot Yellow Label Reims R999 GH Mumm Brut NV Reims R998 Moet & Chandon Brut Imperial Rose Epernay R1187 GH Mumm Brut RosÉ NV R1391 Cuvée Dom Perignon Epernay R2850 Veuve Clicquot Rosé Brut Reims R1399 Mẻthode Cap Classique & Sparkling Wine J. C. Le Roux La Chanson Stellenbosch R153 J. C. Le Roux Le Domaine Stellenbosch R153 Lambrusco Amabile Emilia-Romagna R218 L’ormarins Brut Classique NV Western Cape R232 Pongráçz Brut NV Stellenbosch R253 Minini Prosecco Spumante Veneto R262 Graham Beck Bliss Demi Sec NV Western Cape R289 Genevieve Brut Overberg R290 Saronsberg Brut NV Tulbagh R305 Steenberg Pinot Noir RosÉ NV Constantia R349 L’ormarins Blanc de Blancs Western cape R396 Silverthorn “Genie” RosÉ NV Robertson R426 ✻ White Wine and white blends Sauvignon Blanc Durbanville Hills Durbanville R142 Bouchard Finlayson Walker bay R174 La Motte Franschoek R178 Klein Constantia Constantia R272 Springfield Special Cuvee Robertson R228 Chardonnay De Wetshof Limestone Hill - unwooded Robertson R172 Boschendal 1685 Paarl R205 Oak Valley "Beneath the clouds" Elgin R215 Hamilton Russell Hemel-en-Aarde R599 Babylonstoren Paarl R392 Chenin Blanc Protea Western cape R118 AA Badenhorst “Secateurs” Swartland R172 Nederburg “The Anchor Man” Paarl R282 Not The Usual Suspects... Terra Del Capo Pinot Grigio Franschhoek R145 Neetlingshof Gewurtztraminer – off dry Stellenbosch R148 Spier Creative -

University of Cape Town

The Relativity of Authenticity: Notions of authenticity in the Cape Winelands cultural landscape and the impact of wine tourism on cultural heritage. University of Cape Town A mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of M.Phil in Conservation of the Built Environment (APG5071S) Student: Elize Joubert (SWRELI003) Supervisor: Associate Professor Stephen Townsend School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment University of Cape Town November 2015 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Cover Images: Top photograph: Schoongezicht homestead (www.rustenberg.co.za). Middle photograph: La Motte tourist centre (www.la-motte.com). Bottom photograph: Garden at Babylonstoren (www.bablylonstoren.com). ii Declaration of Free Licence I hereby: 1. grant the University of Cape Town free licence to reproduce the above mini- dissertation in whole or in part, for the purpose of research; 2. declare that: i. the above mini-dissertation is my own unaided work, both in conception and execution, and that apart from the normal guidance of my supervisor, I have received no assistance apart from that stated below; ii. except as stated below, neither the substance or any part of the mini- dissertation has been submitted in the past, or is being, or is to be submitted for a degree in the University or any other University. -

Sp a R K Lin G W H It E R

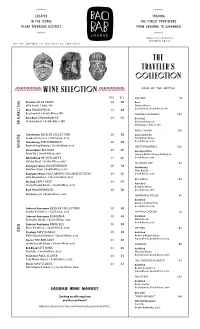

@plantriversidedistrict #baobabloungesav sun.—thu. 3pm–10pm | fri. 3pm–12am | sat. 12pm—12am GLS BTL SALTARE 78 Prosecco VILLA SANDI 10 38 Brut Villa Sandi / Italy, NV Saltare Wines Stellenbosch, South Africa, NV Brut BOSCHENDAL 12 48 Boschendal / South Africa, NV CHARLES HEIDSIECK 132 Brut Rosé GRAHAM BECK 14 55 Brut Rosé Graham Beck / South Africa, NV Charles Heidsieck SPARKLING Champagne, France, NV PAUL CLUVER 136 Chardonnay KESSLER COLLECTION 10 38 Gewürztraminer Kessler Collection / California, 2018 Paul Cluver Wines Chardonnay STELLENBOSCH 15 58 South Africa, 2016 Rustenberg Winery / South Africa, 2018 WHITE GREYTON BARREL 136 Chenin Blanc BIG EASY 13 50 Sauvignon Blanc Ernie Els / South Africa, 2018 Lismore Estate Vineyards Greyton White Blend HELDER CREST 12 46 South Africa, 2014 Helder Crest / South Africa, 2018 FLEUR DU CAP 42 Sauvignon Blanc MULDERBOSCH 10 38 Chardonnay Western Cape / South Africa, 2017 Fluer Du Cap Sauvignon Blanc VILLA MARIA CELLAR SELECTION 13 50 South Africa, 2017 Villa Maria Estate / New Zealand, 2018 BOTANICA 82 Riesling EARLY MIST 12 46 Pinot Noir Vrede En Lust Estate / South Africa, 2017 Botanica Wines Rosé MULDERBOSCH 10 38 South Africa, 2017 Mulderbosch / South Africa, 2018 CHAMONIX ROUGE 46 Red Blend Chamonix Wine Farm South Africa, 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon KESSLER COLLECTION 10 38 Kessler Collection / California, 2018 FAITHFUL HOUND 56 Cabernet Sauvignon KUMUSHA 12 46 Red Blend Kumusha Wines / South Africa, 2019 Mulderbosch South Africa, 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon ERNIE ELS 15 58 Ernie Els Wines /