Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886

THE NAUTILUS 101(1):25-32, 1987 Page 25 . North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886 Robert Hershler Fred G. Thompson Department of Invertebrate Zoology Florida State Museum National Museum of Natural History University of Florida Smithsonian Institution Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Washington, DC 20560, USA ABSTRACT scribed) in the Southwest. Taylor (1966) placed Tryonia in the Littoridininae Taylor, 1966 on the basis of its Anatomical details are provided for the type species of Tryonia turreted shell and glandular penial lobes. It is clear from Stimpson, 1865, Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886, Fonteli- cella Gregg and Taylor, 1965, and Microamnicola Gregg and the initial descriptions and subsequent studies illustrat- Taylor, 1965, in an effort to resolve the systematic relationships ing the penis (Russell, 1971: fig. 4; Taylor, 1983:16-25) of these taxa, which represent most of the generic-level groups that Fontelicella and its subgenera, Natricola Gregg and of Hydrobiidae in southwestern North America. Based on these Taylor, 1965 and Microamnicola Gregg and Taylor, 1965 and other data presented either herein or in the literature, belong to the Nymphophilinae Taylor, 1966 (see Hyalopyrgus Thompson, 1968 is assigned to Tryonia; and Thompson, 1979). While the type species of Pyrgulop- Fontelicella, Microamnicola, Nat ricola Gregg and Taylor, 1965, sis, P. nevadensis (Stearns, 1883), has not received an- Marstonia F. C. Baker, 1926, and Mexistiobia Hershler, 1985 atomical study, the penes of several eastern species have are allocated to Pyrgulopsis. been examined by Thompson (1977), who suggested that The ranges of both Tryonia and Pyrgulopsis include parts the genus may be a nymphophiline. -

The New Zealand Mud Snail Potamopyrgus Antipodarum (J.E

BioInvasions Records (2019) Volume 8, Issue 2: 287–300 CORRECTED PROOF Research Article The New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J.E. Gray, 1853) (Tateidae, Mollusca) in the Iberian Peninsula: temporal patterns of distribution Álvaro Alonso1,*, Pilar Castro-Díez1, Asunción Saldaña-López1 and Belinda Gallardo2 1Departamento de Ciencias de la Vida, Unidad Docente de Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Alcalá, 28805 Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain 2Department of Biodiversity and Restoration. Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (IPE-CSIC). Avda. Montaña 1005, 50059, Zaragoza, Spain Author e-mails: [email protected] (ÁA), [email protected] (PCD), [email protected] (ASL), [email protected] (BG) *Corresponding author Citation: Alonso Á, Castro-Díez P, Saldaña-López A, Gallardo B (2019) The Abstract New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J.E. Gray, 1853) (Tateidae, Invasive exotic species (IES) are one of the most important threats to aquatic Mollusca) in the Iberian Peninsula: ecosystems. To ensure the effective management of these species, a comprehensive temporal patterns of distribution. and thorough knowledge on the current species distribution is necessary. One of BioInvasions Records 8(2): 287–300, those species is the New Zealand mudsnail (NZMS), Potamopyrgus antipodarum https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2019.8.2.11 (J.E. Gray, 1853) (Tateidae, Mollusca), which is invasive in many parts of the Received: 7 September 2018 world. The current knowledge on the NZMS distribution in the Iberian Peninsula is Accepted: 4 February 2019 limited to presence/absence information per province, with poor information at the Published: 29 April 2019 watershed scale. The present study aims to: 1) update the distribution of NZMS in Handling editor: Elena Tricarico the Iberian Peninsula, 2) describe its temporal changes, 3) identify the invaded habitats, Thematic editor: David Wong and 4) assess the relation between its abundance and the biological quality of fluvial systems. -

Holomuzki.Pdf (346.7Kb)

Available online at www.nznaturalsciences.org.nz Same enemy, same response: predator avoidance by an invasive and native snail Joseph R. Holomuzki1,3 & Barry J. F. Biggs2 1Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University, Mansfield, Ohio, U.S.A. 2National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Limited, Christch- urch, New Zealand 3Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] (Received 21 December 2011, revised and accepted 25 April 2012) Abstract Novel or highly effective antipredator traits can facilitate successful invasions by prey species. Previous studies have documented that both the native New Zealand snail, Potamopyrgus antipodarum, and the highly successful, worldwide invader Physella (Physa) acuta, seek benthic cover to avoid fish predators. We asked whether an invasive, South Island population of Physella has maintained this avoidance response, and if so, how it compared to that of Potamopyrgus that has coevolved with native fish. We compared patterns of sediment surface and subsurface use between snail species and between sizes of conspecifics both in a 2nd –order reach with predatory fish and in a laboratory experiment where fish presence (common bullies [Gobiomorphus cotidianus]) was manipulated. Both snails sought protective sediment subsurfaces when with bullies. Proportionally, sediment subsurface use both in field collections and in fish treatments in the experiment were similar between species. Field-captured bullies ate more Physella than Potamoprygus, suggesting different consumptive risks, but overall, few snails were consumed. Instream densities and sizes (shell length) of Physella were greatest on cobbles, where most (>90%) egg masses were found. Potamopyrgus densities were evenly distributed across sand, gravel, and cobbles. -

BASTERIA, 101-113, 1998 Hydrobia (Draparnaud, 1805) (Gastropoda

BASTERIA, Vol 61: 101-113, 1998 Note on the occurrence of Hydrobia acuta (Draparnaud, 1805) (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae) in western Europe, with special reference to a record from S. Brittany, France D.F. Hoeksema Watertoren 28, 4336 KC Middelburg, The Netherlands In August 1992 samples of living Hydrobia acuta (Draparnaud, 1805) have been collected in the Baie de Quiberon (Morbihan, France). The identification is elucidated. Giusti & Pezzoli (1984) and Giusti, Manganelli& Schembri (1995) suggested that Hydrobia minoricensis (Paladilhe, of H. The features ofthe 1875) and Hydrobia neglecta Muus, 1963, are junior synomyms acuta. material from Quiberon support these suggestions: it will be demonstrated that H. minoricensis and H. neglecta fit completely in the conception of H. acuta. H. acuta, well known from the be also distributed in and northwestern Mediterranean, appears to widely western Europe. Key words: Gastropoda,Prosobranchia, Hydrobiidae,Hydrobia acuta, distribution, France. Europe. INTRODUCTION In favoured localities often hydrobiid species are very abundant, occurring in dense populations. Some species prefer fresh water, others brackish or sea-water habitats. in the distributionof Although salinity preferences play a part determining each species, most species show a broad tolerance as regards the degree of salinity. Frequently one live in the habitat with Some hydrobiid species may same another. hydrobiid species often dealt with are in publications on marine species as well in those on non-marine Cachia Giusti species (e.g. et al., 1996, and et al., 1995). Many hydrobiid species are widely distributed, but often in genetically isolated populations; probably due to dif- ferent circumstances ecological the species may show a considerablevariability, especially as to the dimensions and the shape of the shell and to the pigmentation of the body. -

Potamopyrgus Antipodarum POTANT/EEI/NA009 (Gray, 1843)

CATÁLOGO ESPAÑOL DE ESPECIES EXÓTICAS INVASORAS Potamopyrgus antipodarum POTANT/EEI/NA009 (Gray, 1843) Castellano: Caracol del cieno Nombre vulgar Catalán: Cargol hidròbid; Euskera: Zeelanda berriko lokatzetako barraskiloa Grupo taxonómico: Fauna Posición taxonómica Phylum: Mollusca Clase: Gastropoda Orden: Littorinimorpha Familia: Hydrobiidae Observaciones Sinonimias: taxonómicas Hydrobia jenkinsi (Smith, 1889), Potamopyrgus jenkinsi (Smith, 1889) Resumen de su situación e Especie con gran capacidad de colonización y alta tasa impacto en España reproductiva, que produce poblaciones muy abundantes, produciendo una modificación de la cadena trófica de los ecosistemas acuáticos; desplazamiento y competencia con especies autóctonas e impacto en las infraestructuras acuáticas. Normativa nacional Catálogo Español de Especies Exóticas Invasoras Norma: Real Decreto 630/2013, de 2 de agosto. Fecha: (BOE nº 185 ): 03.08.2013 Normativa autonómica - Normativa europea - La Comisión Europea está elaborando una legislación sobre especies exóticas invasoras según lo establecido en la actuación 16 (crear un instrumento especial relativo a las especies exóticas invasoras) de la “Estrategia de la UE sobre la biodiversidad hasta 2020: nuestro seguro de vida y capital natural” COM (2011) 244 final, para colmar las lagunas que existen en la política de lucha contra las especies exóticas invasoras. Acuerdos y Convenios - Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica (CBD), 1992. internacionales - Convenio relativo a la conservación de la vida silvestre y del medio natural de Europa. Berna 1979.- Estrategia Europea sobre Especies Exóticas Invasoras (2004). - Convenio internacional para el control y gestión de las aguas de lastre y sedimentos de los buques. Potamopyrgus antipodarum Página 1 de 3 Listas y Atlas de Mundial Especies Exóticas - Base de datos del Grupo Especialista de Especies Invasoras Invasoras (ISSG), formado dentro de la Comisión de Supervivencia de Especies (SSC) de la UICN. -

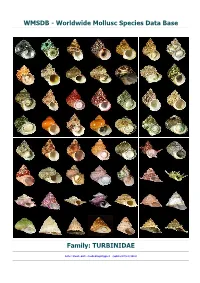

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Malacologia Vol. 56, No. 1-2 2013 Contents Full Papers

MALACOLOGIA VOL. 56, NO. 1-2 MALACOLOGIA 2013 http://malacologia.fmnh.org CONTENTS World’s Leading Malacological Journal FULL PAPERS Journal Impact Factor 1.592 (2012) Suzete R. Gomes, David G. Robinson, Frederick J. Zimmerman, Oscar Obregón & Nor- Founded in 1961 man B. Barr Morphological and molecular analysis of the Andean slugs Colosius confusus, n. sp., a newly recognized pest of cultivated flowers and coffee from Colombia, Ecuador and EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Peru, and Colosius pulcher (Colosi, 1921) (Gastropoda, Veronicellidae) ..... 1 GEORGE M. DAVIS Eva Hettenbergerová, Michal Horsák, Rashmi Chandran, Michal Hájek, David Zelený & Editorial Office Business & Subscription Office Jana Dvořáková Malacologia Malacologia Patterns of land snail assemblages along a fine-scale moisture gradient .... 31 P.O. Box 1222 P.O. Box 385 Nicolás Bonel, Lía C. Solari & Julio Lorda West Falmouth, Massachusetts 02574, U.S.A. Haddonfield, New Jersey 08033, U.S.A. Differences in density, shell allometry and growth between two populations of Lim- [email protected] [email protected] noperna fortunei (Mytilidae) from the Río de la Plata basin, Argentina ..... 43 Mariana L. Adami, Guido Pastorino & J. M. (Lobo) Orensanz Copy Editor Associate Editor Phenotypic differentiation of ecologically significant Brachidontes species co- EUGENE COAN JOHN B.BURCH occurring in intertidal mussel beds from the southwestern Atlantic ........ 59 Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History University of Michigan Santa Barbara, California, U.S.A. Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Moncef Rjeibi, Soufia Ezzedine-Najai, Bachra Chemmam & Hechmi Missaoui [email protected] [email protected] Reproductive biology of Eledone cirrhosa (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) in the northern and eastern Tunisian Sea (western and central Mediterranean) .. -

Porin Expansion and Adaptation to Hematophagy in the Vampire Snail

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Piercing Fishes: Porin Expansion and Adaptationprovided by Archivio to istituzionale della ricerca - Università di Trieste Hematophagy in the Vampire Snail Cumia reticulata Marco Gerdol,1 Manuela Cervelli,2 Marco Oliverio,3 and Maria Vittoria Modica*,4,5 1Department of Life Sciences, Trieste University, Italy 2Department of Biology, Roma Tre University, Italy 3Department of Biology and Biotechnologies “Charles Darwin”, Sapienza University, Roma, Italy 4Department of Integrative Marine Ecology, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Naples, Italy 5UMR5247, University of Montpellier, France *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Associate Editor: Nicolas Vidal Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article-abstract/35/11/2654/5067732 by guest on 20 November 2018 Abstract Cytolytic pore-forming proteins are widespread in living organisms, being mostly involved in both sides of the host– pathogen interaction, either contributing to the innate defense or promoting infection. In venomous organisms, such as spiders, insects, scorpions, and sea anemones, pore-forming proteins are often secreted as key components of the venom. Coluporins are pore-forming proteins recently discovered in the Mediterranean hematophagous snail Cumia reticulata (Colubrariidae), highly expressed in the salivary glands that discharge their secretion at close contact with the host. To understand their putative functional role, we investigated coluporins’ molecular diversity and evolu- tionary patterns. Coluporins is a well-diversified family including at least 30 proteins, with an overall low sequence similarity but sharing a remarkably conserved actinoporin-like predicted structure. Tracking the evolutionary history of the molluscan porin genes revealed a scattered distribution of this family, which is present in some other lineages of predatory gastropods, including venomous conoidean snails. -

Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers Soilam Boutoumit 1,2,* , Oussama Bououarour 1 , Reda El Kamcha 1 , Pierre Pouzet 2 , Bendahhou Zourarah 3, Abdelaziz Benhoussa 1, Mohamed Maanan 2 and Hocein Bazairi 1,4 1 BioBio Research Center, BioEcoGen Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 4 Avenue Ibn Battouta, Rabat 10106, Morocco; [email protected] (O.B.); [email protected] (R.E.K.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (H.B.) 2 LETG UMR CNRS 6554, University of Nantes, CEDEX 3, 44312 Nantes, France; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (M.M.) 3 Marine Geosciences and Soil Sciences Laboratory, Associated Unit URAC 45, Faculty of Sciences, Chouaib Doukkali University, El Jadida 24000, Morocco; [email protected] 4 Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Europa Point Campus, University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar GX11 1AA, Gibraltar * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study presents an assessment of the diversity and spatial distribution of benthic macrofauna communities along the Moulay Bousselham lagoon and discusses the environmental factors contributing to observed patterns. In the autumn of 2018, 68 stations were sampled with three replicates per station in subtidal and intertidal areas. Environmental conditions showed that the range of water temperature was from 25.0 ◦C to 12.3 ◦C, the salinity varied between 38.7 and 3.7, Citation: Boutoumit, S.; Bououarour, while the average of pH values fluctuated between 7.3 and 8.0. -

Species Distinction and Speciation in Hydrobioid Gastropoda: Truncatelloidea)

Andrzej Falniowski, Archiv Zool Stud 2018, 1: 003 DOI: 10.24966/AZS-7779/100003 HSOA Archives of Zoological Studies Review inhabit brackish water habitats, some other rivers and lakes, but vast Species Distinction and majority are stygobiont, inhabiting springs, caves and interstitial hab- itats. Nearly nothing is known about the biology and ecology of those Speciation in Hydrobioid stygobionts. Much more than 1,000 nominal species have been de- Mollusca: Caeno- scribed (Figure 1). However, the real number of species is not known, Gastropods ( in fact. Not only because of many species to be discovered in the fu- gastropoda ture, but mostly since there are no reliable criteria, how to distinguish : Truncatelloidea) a species within the group. Andrzej Falniowski* Department of Malacology, Institute of Zoology and Biomedical Research, Jagiellonian University, Poland Abstract Hydrobioids, known earlier as the family Hydrobiidae, represent a set of truncatelloidean families whose members are minute, world- wide distributed snails inhabiting mostly springs and interstitial wa- ters. More than 1,000 nominal species bear simple plesiomorphic shells, whose variability is high and overlapping between the taxa, and the soft part morphology and anatomy of the group is simplified because of miniaturization, and unified, as a result of necessary ad- aptations to the life in freshwater habitats (osmoregulation, internal fertilization and eggs rich in yolk and within the capsules). The ad- aptations arose parallel, thus represent homoplasies. All the above facts make it necessary to use molecular markers in species dis- crimination, although this should be done carefully, considering ge- netic distances calibrated at low taxonomic level. There is common Figure 1: Shells of some of the European representatives of Truncatelloidea: A believe in crucial place of isolation as a factor shaping speciation in - Ecrobia, B - Pyrgula, C-D - Dianella, E - Adrioinsulana, F - Pseudamnicola, G long-lasting completely isolated habitats. -

Folia Malacologica

FOLIA Folia Malacol. 23(4): 263–271 MALACOLOGICA ISSN 1506-7629 The Association of Polish Malacologists Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe Poznań, December 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.023.022 TANOUSIA ZRMANJAE (BRUSINA, 1866) (CAENOGASTROPODA: TRUNCATELLOIDEA: HYDROBIIDAE): A LIVING FOSSIL Luboš BERAN1, SEBASTIAN HOFMAN2, ANDRZEJ FALNIOWSKI3* 1Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, Regional Office Kokořínsko – Máchův kraj Protected Landscape Area Administration, Česká 149, CZ 276 01 Mělník, Czech Republic 2Department of Comparative Anatomy, Institute of Zoology, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 9, 30- 387 Cracow, Poland 3Department of Malacology, Institute of Zoology, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 9, 30-387 Cracow, Poland (e-mail: [email protected]) * corresponding author ABSTRACT: A living population of Tanousia zrmanjae (Brusina, 1866) was found in the mid section of the Zrmanja River in Croatia. The species, found only in the freshwater part of the river, had been regarded as possibly extinct. A few collected specimens were used for this study. Morphological data confirm the previous descriptions and drawings while molecular data place Tanousia within the family Hydrobiidae, subfamily Sadlerianinae Szarowska, 2006. Two different sister-clade relationships were inferred from two molecular markers. Fossil Tanousia, represented probably by several species, are known from interglacial deposits of the late Early Pleistocene to the early Middle Pleistocene -

Turritella Communis (Risso, 1826)

ΣΧΟΛΗ ΘΕΤΙΚΩΝ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΩΝ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΑΣ ΤΟΜΕΑΣ ΓΕΝΙΚΗΣ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΙΑΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΓΕΩΔΥΝΑΜΙΚΗΣ ΕΡΓΑΣΤΗΡΙΟ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΙΑΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΦΥΣΙΚΗΣ ΩΚΕΑΝΟΓΡΑΦΙΑΣ ΜΙΚΡΟΠΑΛΑΙΟΝΤΟΛΟΓΙΚΕΣ ΑΝΑΛΥΣΕΙΣ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΙΩΝ ΙΖΗΜΑΤΩΝ ΤΟΥ ΑΜΒΡΑΚΙΚΟΥ ΚΟΛΠΟΥ Μεταπτυχιακή Φοιτήτρια Αρκαδιανού Μαρία Επιβλέπουσα Καθηγήτρια: Γεραγά Μαρία Τριμελής Επιτροπή: Γεραγά Μαρία Παπαθεοδώρου Γεώργιος Ηλιόπουλος Γεώργιος 0 Πάτρα, 2019 Αφιερώνεται στην οικογένειά μου που με στηρίζει σε κάθε νέο ξεκίνημα σε κάθε απόφαση… Ευχαριστίες… Θα ήθελα να ευχαριστήσω τους καθηγητές Γεραγά Μαρία και Παπαθεοδώρου Γεώργιο που μου έδωσαν τη δυνατότητα να εκπονήσω τη διπλωματική μου εργασία στον τομέα της Περιβαλλοντικής Ωκεανογραφίας δείχνοντάς μου εμπιστοσύνη και προσφέροντάς μου πολύτιμη βοήθεια. Τον καθηγητή μου Ηλιόπουλο Γεώργιο και την Δρ. Παπαδοπούλου Πηνελόπη για την πολύτιμη βοήθεια τους, την καθοδήγηση, τις χρήσιμες συμβουλές και τη στήριξη. Την Υποψήφια Διδάκτορα Τσώνη Μαρία για τις συμβουλές της στο χειρισμό ορισμένων λογισμικών. Την Υποψήφια Διδάκτορα Πρανδέκου Αμαλία για τις συμβουλές της. Τον φίλο μου Ανδρέα για τη στήριξη και την υπομονή του. Τέλος, θέλω να εκφράσω ένα μεγάλο ευχαριστώ στην οικογένειά μου που με στήριξε με κάθε τρόπο σε όλη τη διάρκεια των σπουδών μου και υπήρξαν σημαντικοί αρωγοί όλα αυτά τα χρόνια. 1 Ευχαριστίες……………………………………………………………………………………………………….....................1 ΕΙΣΑΓΩΓΗ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Σκοπός…………………………………………………………………………………………………..................3 1. ΠΕΡΙΟΧΗ ΜΕΛΕΤΗΣ………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1.1Γενικά …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3