The Deserted Village of Jay Parini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Gwyn Conger Steinbeck the Story

For Immediate Release Lawson Publishing LTD. Discovered--GWYN CONGER STEINBECK. New book relates love and adventures of the "forgotten wife," muse to the Nobel Prizewinning author of American classics MY LIFE WITH JOHN STEINBECK: by Gwyn Conger Steinbeck The Story of John Steinbeck's Forgotten Wife Who was Gwyn Conger Steinbeck? Unlike Steinbeck's first and third wives, she's unmentioned in standard editions of classics, such as The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. But that's about to change with the publication of MY LIFE WITH JOHN STEINBECK: by Gwyn Conger Steinbeck, The story of John Steibeck's Forgotten Wife. (Lawson Publishing Ltd. Sept. 6th.). The ms, lost since 1972, was recently discovered in Wales. The book includes her introduction, that of journalist Douglas G. Brown and the acclaimed John Steinbeck biographer, Jay Parini. The book reveals the missing voice of Gwyn, "the forgotten wife," mother of his two sons, during a 6-year marriage that included the tumult of World War 2.. When she met Steinbeck in 1939, Gwyn was a professional singer, working for RKO radio and CBS in L.A. She was an independent young woman, lively and radiant in her love for the great man wooing her--14 years her senior. He was impressed by her beauty and magnetic presence. For women of her era, many of whom had to leave jobs after the war, marriage was considered a woman's true career-- love was life. This journal is her story of that adventure, often "on the road" with a restless Steinbeck, criss-crossing continents and making homes. -

Dijkstra Agency Hot List

DIJKSTRA AGENCY HOT LIST Fall 2017 – Spring 2018 Sandra Dijkstra Elise Capron * Jill Marr * Thao Le Andrea Cavallaro * Roz Foster Jessica Watterson * Suzy Evans Jennifer Kim www.dijkstraagency.com NEW MEMOIR FROM BESTSELLING AUTHOR AMY TAN WHERE THE PAST BEGINS: A Writer’s Memoir Amy Tan (Ecco, October 2017) An exploration of memory, emotion, and the workings of the imagination in the mind of the writer, from the inimitable Amy Tan. Where the Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir presents Amy Tan, a master of storytelling, offering unparalleled access into her writing process, her fascination with the neurology of creativity, and her exploration of the family histories that led to the creation of indelible characters in beloved works such as The Joy Luck Club and The Valley of Amazement. In these pages, we find hints of trauma in Tan’s past, relationships she has never discussed publicly, and a family mystery that was only solved accidentally, by stumbling on a box of old documents. In evocative descriptions and characteristic humor, this memoir offers us a vivid picture of the author’s childhood in Northern California, the world of her mother and grandmother in China, and her recent forays into plein air sketching. Amy explores how memories, the inspiration of music, and the beauty of the natural world mingle with enigmatic characteristics of the writer’s brain and imaginative capacities to create the magic of a story. Other non-fiction by Amy Tan: THE OPPOSITE OF FATE: Memories of a Writing Life (Putnam, 2003) New York Times bestseller, New York Times notable book “Sharp and invigorating…fertile reading.”— The New York Times Book Review “Wickedly funny and honest.”— O Magazine “A melodramatic, tragic and comedic tale…Tan is refreshingly candid.”— Baltimore Sun Amy Tan is the internationally bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club, The Kitchen God’s Wife, The Hundred Secret Senses, The Bonesetter’s Daughter, The Valley of Amazement, The Opposite of Fate: Memories of a Writing Life, and two children’s books. -

The Novel's Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State English Theses English 8-2012 Survival of the Fictiveness: The oN vel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability Jesse Mank Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Dr. Aimable Twagilimana, Professor of English First Reader Dr. Barish Ali, Assistant Professor of English Department Chair Dr. Ralph L. Wahlstrom, Associate Professor of English To learn more about the English Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://english.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Mank, Jesse, "Survival of the Fictiveness: The oN vel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability" (2012). English Theses. Paper 5. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/english_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Survival of the Fictiveness: The Novel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability by Jesse Mank An Abstract of a Thesis in English Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2012 State University of New York College at Buffalo Department of English Mank i ABSTRACT OF THESIS Survival of the Fictiveness: The Novel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability The novel is a problematic literary genre, for few agree on precisely how or why it rose to prominence, nor have there ever been any strict structural parameters established. Terry Eagleton calls it an “anti-genre” that “cannibalizes other literary modes and mixes the bits and pieces promiscuously together” (1). And yet, perhaps because of its inability to be completely defined, the novel best represents modern thought and sensibility. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

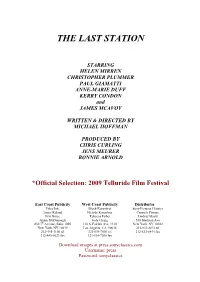

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at www.neh.gov/grants/education/enduring-questions for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: NEH Enduring Questions Course on Literature and Morality Institution: University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Project Director: Padma Viswanathan Grant Program: Enduring Questions 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 302, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Can Good Books Make Us Better People? Our search, in stories, for how to be. Padma Viswanathan, University of Arkansas Anecdote and science both have advanced the theory that reading fiction can make us more compassionate. James Wood, in How Fiction Works, quotes a Mexican police chief who prescribed literature to his officers because, he said, “Risking your life to save other people’s lives and property requires deep convictions. -

Review of Jay Parini, the Passages of Herman Melville Celia Wallhead

Testimonies on Herman Melville: Review of Jay Parini, The Passages of Herman Melville Celia Wallhead (University of Granada, Spain) Jay Parini, The Passages of Herman Melville Edinburgh: Canongate, 2011 ISBN: 978-1-847-67979-6 (HB) £ 17.99 New York: Doubleday, 2010 ISBN: 978-0-385-52277-9 (HB) $ 26.95 ***** Jay Parini‟s novel of the life of the author of Moby-Dick (1851) is described on the dust-jacket as “stirring” and “mesmerising”, providing for the first time a “clear view” of a great writer who, as a man, was both sympathetic and maddening. Parini‟s strategy to achieve this paradoxical effect is to write from several different, equally convincing perspectives, managing to reconcile the biographical pact with truthfulness and the flights of the imagination proper to the novelistic domain. The novel thus falls squarely into the category of neo-Victorian bio-fiction, which deals with real historical figures while inventing some of the contexts in which they find themselves and supplementing the facts already known about them. As a successful poet, novelist and critic, Parini has experience in both fictional and non-fictional genres. Axinn Professor of English at Middlebury College, Vermont, and visiting Fellow at Christchurch College, Oxford, as well as a one-time Fellow at the University of London, he is the author of biographies of Robert Frost and John Steinbeck, while his studies of the lives of Walter Benjamin and Tolstoy have taken the form of novels instead. Much as Tracy Chevalier‟s Burning Bright (2007) concentrates on just over a year in the life of William Blake, Parini‟s The Last Station: A Novel of Tolstoy’s Last Year (1990) distils the life of another literary genius and contemporary of Herman Melville into the final year, 1910, of the writer‟s life. -

Does American Exceptionalism Make Us Dumb? (Opinion) - CNN.Com 4/1/15, 16:58

Does American exceptionalism make us dumb? (Opinion) - CNN.com 4/1/15, 16:58 U.S. Edition New York City, NY 50° Sign in | MyCNN News Video TV Opinions More… Search CNN Political Op-Eds Social Commentary iReport Does American exceptionalism make us dumb? By Jay Parini Updated 2:51 PM ET, Tue February 24, 2015 Advertisement Voices Johnson: Giuliani's Obama comments 'regrettable' 01:06 Story highlights Editor's Note: Jay Parini, a poet and novelist, teaches at Middlebury College in Vermont. He has just published "Jesus: The Human Face of Indiana's other God," a biography of Jesus. The opinions expressed in this commentary Jay Parini: Giuliani, Oklahoma AP history issue are solely those of the author. have put focus on American exceptionalism outrageous law (CNN)—Talk of American exceptionalism has become By Sally Kohn, CNN Political Commentator Parini says U.S. holds high, noble ideals and headline news, with loud sputtering from Rudy Giuliani, struggles to improve on flaws 'Daily Show' missed an opportunity who suggested that President Barack Obama doesn't To whitewash our history dishonors our values, love America in the same way that the rest of us do. Indiana's problem has an easy fix he says Giuliani wants to dwell on our exceptionalism -- the idea A dreamer gets a driver's license that we're different from other countries, and much better. Will psychiatrists keep dangerous secrets? It's an old idea that Obama took on in the second year of his presidency, when he said: "I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and Why we need a middle-class http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/24/opinion/parini-american-exceptionalism/ Page 1 of 9 Does American exceptionalism make us dumb? (Opinion) - CNN.com 4/1/15, 16:58 the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism." president That comment annoyed those who wished him to say: Kill the college credit hour "America is the best country in the world, bar none!" President Obama's unrecognized Somehow the drumbeat for exceptionalism continues. -

A Conversation with John Irving

Academic Forum 26 2008-09 A Conversation with John Irving Michael Ray Taylor, M.F.A. Professor of Mass Media Communication ABSTRACT: In an interview with John Irving, conducted via email in October 2008 for the Nashville Scene , Michael Ray Taylor asks the noted author questions about his current work, his literary legacy, the state of literature in America, and the value of Irving’s graduate training at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. “If you are lucky enough to find a way of life you love,” John Irving once wrote, “you have to find the courage to live it.” And live it he has. The author of such best-selling novels as The World According to Garp , The Hotel New Hampshire , Cider House Rules , A Prayer for Owen Meany —not to mention his screenplay adaption of Cider House Rules , for which he received an Academy Award in 2000—has become, perhaps more than any living writer, the sort of Novelist for whom the term was always capitalized a hundred years ago: a crafter of rich, complex books that not only chronicle the lives of the people who populate them, but of a generation, specifically Americans who came of age in the 1960s and ‘70s. With the same obsessive drive he once brought to wrestling—a sport in which he competed until the age of 37—the 66-year-old writer has time and again mastered the “big” novel, shaping and revising each book over a period as long as five or six years before letting it go to, more often than not, immense popular and critical acclaim. -

The Last Station

THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink. Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Janice Roland Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik Annie McDonough Judy Chang 550 Madison Ave 850 7th Avenue, Suite 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax Download images at press.sonyclassics.com Username: press Password: sonyclassics SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. -

This Is Just a Test to See What This Computer Can Do

Tony Magistrale Professor, Department of English 301 Old Mill University of Vermont Burlington, VT 05405-0114 802.656.4039 [email protected] Employment History 1997-present Professor of English, University of Vermont. 2009-2012 Chair, English Department, University of Vermont 2004-09 Associate Chair, English Department, University of Vermont 2005-09 Research Consultant for novelist Stephen King 1999-2004 Director, Undergraduate Advising, English Department, University of Vermont 1989-97 Associate Professor of English [tenured 1989], University of Vermont. 1988-91 Director, Freshman Composition Program, University of Vermont. 1983-89 Assistant Professor of English, University of Vermont. 1982-83 Fulbright Post-Doctoral Fellow, University of Milan, Italy. 1981-82 Visiting Lecturer, University of Vermont. 1979-80 Mellon Pre-Doctoral Fellow, University of Pittsburgh. 1974-76 Lecturer, Erie Community College, Buffalo, New York. Educational Record 1981 Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh. 1976 M.A. English, University of Pittsburgh. 1 1974 B.A. English, cum laude, Allegheny College, Meadville, Pennsylvania. Honors and Awards 2020 Winner of the Carl Bode Award for Outstanding Article (“The Vietnamization of Stephen King”) published in the Journal of American Culture, AY 2020. Unanimous selection of an international award selected by editors of the journal and administrative staff of the Popular Culture Association. 2019 “The Lunch” one of six finalists for the 2019 Jack Grapes Poetry Prize. 1200 entries of two poems each from poets worldwide (over 75 countries and 47 of the 50 U.S. states), comprising more than 2000 poems in an international competition judged by three major American poets: https://www.culturalweekly.com/2019-jack-grapes-poetry-prize-winners/ 2017 Tourism Award of Excellence from Destination Mansfield-Richland County, Ohio for The Shawshank Experience: Tracking the History of the World’s Most Popular Movie.