The Enduring Struggle Over Professionalism in English Football from 1883 to 1963: a Marxist Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

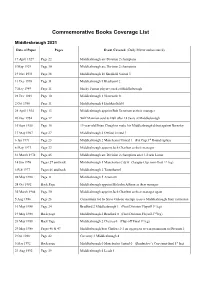

Middlesbrough Edition

Commemorative Books Coverage List Middlesbrough 2021 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 17 April 1927 Page 22 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions 5 May 1929 Page 30 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions 19 Nov 1933 Page 38 Middlesbrough 10 Sheffield United 3 11 Dec 1938 Page 31 Middlesbrough 9 Blackpool 2 7 May 1949 Page 11 Micky Fenton player-coach at Middlesbrough 28 Dec 1949 Page 10 Middlesbrough 1 Newcastle 0 2 Oct 1950 Page 11 Middlesbrough 8 Huddersfield 0 28 April 1954 Page 13 Middlesbrough appoint Bob Dennison as their manager 26 Dec 1954 Page 17 Wilf Mannion sold to Hull after 18 years at Middlesbrough 16 Sept 1955 Page 16 19 year-old Brian Clough to make his Middlesbrough debut against Barnsley 17 May 1967 Page 27 Middlesbrough 4 Oxford United 1 6 Jan 1971 Page 23 Middlesbrough 2 Manchester United 1 (FA Cup 3rd Round replay) 8 May 1973 Page 32 Middlesbrough appoint Jack Charlton as their manager 31 March 1974 Page 45 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions after 1-0 win Luton 14 Jan 1976 Pages 27 and back Middlesbrough 1 Manchester City 0 (League Cup semi-final 1st leg) 6 Feb 1977 Pages 46 and back Middlesbrough 2 Tottenham 0 20 May 1980 Page 31 Middlesbrough 5 Arsenal 0 24 Oct 1982 Back Page Middlesbrough appoint Malcolm Allison as their manager 30 March 1984 Page 30 Middlesbrough appoint Jack Charlton as their manager again 5 Aug 1986 Page 26 Consortium led by Steve Gibson attempt to save Middlesbrough from extinction 16 May 1988 Page 24 Bradford 2 Middlesbrough 1 (First Division Playoff 1st -

Think of the Consequences

NHSCA EDITORIAL September 2014 Think of the consequences This July, a passenger aircraft was shot down such clinics are usually staffed by GPs with a over Ukraine by a ground–to–air missile which, Special Interest (GPSIs), many of whom do not it seems likely, was provided to one of the fulfil the supposedly mandatory experience armed groups in the area by a third party. This and training criteria for such posts. David Eedy appalling event raises many issues, including points out that the use of these ‘community’ the immorality of the arms trade and the results clinics has never been shown to reduce hospital of interference in a neighbouring country’s waiting lists, they threaten to destabilise the territory and politics, and beyond this there are hospital service and they cost a lot more than the issues of unforeseen consequences. Those hospital clinics. The service thus provided is operating this complex modern equipment not acting as a useful filter to reduce hospital almost certainly had no intention of annihilating referrals and causes only delay in reaching a true 298 innocent travellers, neither, presumably, specialist service. Further, we cannot ignore the did the providers think they might. It seems inevitable impact of this continued outsourcing likely that inadequate training, against a on education of students and trainees as the background of inexperience of such dangerous service is fragmented. At a recent public equipment, resulted in this disaster. Unforeseen, meeting a woman who had attended a local but not unforeseeable. private sector dermatology clinic told us that she could not fault the service - everyone was very Nearer to home, we are increasingly aware of professional and the surroundings pleasant - decisions about clinical services made by those except that they could not deal with her problem who know little about them, do not wish to look and she had to be referred on to the hospital. -

Georgia High School Association State Football Championships Georgia High School Association State Football Championships

GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS taBLE OF contents FEATURES 2011 State SPONSOR INDEX Letter from the Executive Director 3 Verizon 2 Georgia Dome Information 5 CHAMPionsHIPS Wilson 2 The Athletic Image 4 GPB Coverage 23 Friday, December 9 Georgia Meth Project 4 Fall Champions 25 Class AA Championship Sports Med South 4 GACA Hall of Fame 26 4:30 p.m. Buford vs. Calhoun Mizuno 16 Sportsmanship Award 27 Class AAAA Championship GA Army National Guard 16 Past State Champions 29 8:00 p.m. Lovejoy vs. Tucker Gatorade 18 Georgia EMC 18 Sports Authority 20 TEAM INFORMATION Saturday, December 10 Georgia Photographics 20 Class AAAAA Team Information 6-7 Class A Championship Marines 21 Class AAAA Team Information 8-9 1:00 p.m. Savannah Chr. vs. Landmark Chr. Choice Hotel 21 Class AAA Team Information 10-11 Class AAA Championship Musco Lighting 22 Class AA Team Information 12-13 4:30 p.m. Burke Co. vs. Peach Co. Bauerfeind 22 Class A Team Information 14-15 Class AAAAA Championship Score Atlanta 24 PlayOn Sports 26 Class AAAAA Bracket 17 8:00 p.m. Grayson vs. Walton Regions Bank 28 Class AAAA Bracket 17 All games will be televised live in HD on Georgia Public Broad- Jostens 28 Class AAA Bracket 19 casting, streamed live on GPB.org and GHSA.tv and available by Field Turf 30 radio on the Georgia News Network, which are available to GNN’s Class AA Bracket 19 statewide radio network of 115 affiliates. The games will be avail- Team IP 30 Class A Bracket 20 able On Demand at GPB.org/sports and GHSA.tv and rebroadcast Georgia Public Broadcasting 31 next week on GPB Knowledge on Atlanta Comcast channel 246 or statewide on over-the-air service at the .3 digital channel. -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

The Stanley Show

Introduction: The Stanley Show Stanley Matthews turned matter-of-factly, his stare fixed to avoid eye contact. His expression, washed of emotion, accentuated the slightly sunken, careworn look that made him appear at least as old as his thirty-two years. Time had already gone to work on his hair. It was combed back and still dark but was in the first stages of retreat. In close-up, something seemed to shadow his features, a sadness possibly pleated in the corners of his mouth. No one could have guessed that here was a man at the soaring peak of his powers who had just brought a packed arena to a ferment of excitement. As Matthews turned, gently hitching the elastic of his loose- fitting shorts on to his hips, the sellout crowd of 75,000 at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels had started to applaud. Moments earlier, England’s outside-right had completed a run that even by his standards was exceptional, bewildering Belgium’s defence and electrifying the spectators. And that was not the end of this particular piece by Matthews on a pitch made treacherous by a violent cloudburst soon after kick-off. Having wrought havoc with the ball on the turf, he dipped his head, cocked his right boot and lifted the ball over the oncoming keeper. One reporter likened it to a golf shot, Matthews seizing a wedge and lofting The Wizard pages.indd 1 23/01/2014 11:15 2 jon henderson the ball in a meticulous arc. All that was left for Tom Finney to do to collect his second goal of the match was to deflect his header into an unguarded net. -

198485EC1RH.Pdf

eYQhr {s t\. - h - I tfrs{; ,'hp A*r *ffs I $s\ *Fi N 'ru'd 'tu'd g6'tf SU3ddnS UVg ge'Z-ZLSJHONn'l UVS gLffi $A0l :pL N330U38V lSlUlS I3)UVW Zr rnoraoI srqbrlÄ1t3 qllM LHgtN NOll-VU8l'133^eprnles . inolag I stq6r1Ä1t3 t{l!M u e 00 Z- u d Ot I lHglN ^tUVd ,{epu3 . Jnolao qrrMlNlLl|NtVlUJtNS t^t"l I OJSTO^ePsrnqf . slq6r'l^lr3 pueg tueprsaulHgtN JtSnW UV]ndOd ^epsaupoM . i^treaauo] auorlaM auo^ra^3- 8n"13 NUllSlM I ^UINnOO ^epsanl . 'Of,SlO crsnhliloU u, loou a^rl s09pue sog^epuol l . 'l'lv luauureualu]a^rt u e m !- u d O€Z! UVlnJVtf,:ldS ^VO ^epuns . slH9tN 4 - lNSl lNlvluSrNS 3Al1 NMOI SHl JO )]Vr ot'l {u31s3cr9'll^ldvf, !' s9NlwwlH ^8 CllNrUd 'sr{}uoru mal }xau tt60e9 (tazoll8t99zeg (lz0l :auoqoatal aql ul aurof, o1 slq6gu ueadornE legeadsasoql ro alolrr srStroHd sl80ds ' ' ' ^s 03Hs|rand € o3cnooud mal s pup lcadsord u1 raquraruar ol rlf,lptu raqloup lNtzvSvW ^vcHf,lvr/! Noo lHl 'tz6t s.alaql leql adoq a/n pue 6uguanastql uollgladuoc 086r llp :steuulM dnC q6nolg^tO qnlf, s.adorng ut aq o1 1ear6 s.11 lsotuaro; {Jpq '99-996t 'suol1lladuoJ tt-9161 f,llsatI|oPsP lla/n sP sluarueurnol ueadorng :sJsuulM dnC sn6ea7 qslrto'S aarql aql u! prof,ar lsed s,qn1caql lunof,Jp pallelap Io 'Iooq 9t-9t6t e sappord '6u1uanaslql punor6 aql punoJe alss uo :sreuulM dn3 en6ea7 qsutoo9 ute.ltnoS 'adornE reaf mau s.qnlJ aql uaql u! proJal lsed suoq aql m6r't86r'z8f,L'oL6l' Lt6- :steuulM dnc qsluocs le {ool pue sa6ed aq} {rpq utn} ol a{ll Plnom no/{;1 puy 'ullrag t8-886t 08-5a61'99-!e6r oureufq uro{ sro}!s!Arno lp {ool pallplap e snld :d!qsuordueqC en6ee7 podar -

Title Information

Title information Arsenal Match of My Life Gunners Legends Relive Their Greatest Games By Alex Crook and Pat Symes Key features • Part of the popular and successful Match of My Life series which features a number of football clubs • Never before have the club’s greatest players come together to relive their greatest matches and time at the club in exclusive, personal interviews • Includes contemporary and historic images from the legendary matches covered • Written by journalist and broadcaster Alex Crook, who covers Arsenal for TalkSport Radio, and experienced football reporter Pat Symes • Foreword by George Graham and bonus chapter by Arsenal fan, journalist and TV personality Piers Morgan • Publicity campaign planned including radio, newspapers, websites and magazines Description More than 20 Arsenal legends join together to offer a unique insight into the most magic moments in the history of one of the world’s biggest clubs. Gunners greats from David Seaman to Bob Wilson and Theo Walcott to Charlie George take us behind the dressing- room door, enabling fans of all ages to relive these amazing memories through the eyes and emotions of the men who were there, pulling on the famous red-and-white shirts. Featuring previously untold stories from fan favourites including Ray Parlour on winning the Premier League title at Old Trafford and scoring the winner in the FA Cup Final in the space of just four days and what Arsene Wenger did to transform the club. Lee Dixon reveals how he and his team-mates toasted their remarkable last-gasp 1989 title win at Anfield by swigging Kenny Dalglish’s champagne while George Graham offers a rare look back at his amazing Highbury career as both player and manager. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Advanced Information

Title information The Leeds United Collection A History of the Leeds Kits By Robert Endeacott Key features • Brings to life over 100 years of history for this special club, with eye-catching photos of rare and historic Leeds United shirts and paraphernalia throughout • A wealth of anecdotes, exclusive interviews and quotes from many big names connected with the club – players, managers, personnel and supporters • Features all Leeds kits, from the club’s formation in 1919 to the present day • Robert Endeacott is a Leeds supporter of more than 50 years’ standing and has written extensively about the club in numerous books and articles • Pictures by renowned sports photographer Andrew Varley; foreword by Leeds United legend Eddie Gray • Publicity campaign planned including radio, newspapers, websites, podcasts and magazines Description The Leeds United Collection takes you on a fascinating multi-coloured journey through the club’s history from 1919 to the present day. With stunning photos of unique match-worn Leeds shirts and other paraphernalia, the book tells the Whites’ story alongside anecdotes, interviews and quotes from many big names. See home and away shirts worn by Leeds legends from various eras including Billy Bremner and Albert Johanneson, David Batty, Gary Speed, Peter Lorimer, Paul Madeley, Paul Reaney, Norman Hunter, Mick Jones, Allan Clarke, Frank and Eddie Gray, Terry Yorath, John Sheridan, Ian Baird, Fabian Delph, Kalvin Phillips, Pablo Hernandez and many more. These superb images are brought to life with commentary on title- and trophy-winning seasons, plus promotion-winning campaigns. There are also interviews with Eddie Gray, Howard Wilkinson, Pablo Hernandez, Allan Clarke, Tony Currie, Jermaine Beckford, Aidan Butterworth, Simon Grayson, Brian Deane, Rod Wallace, Dominic Matteo and many more. -

STONEHOUSE HERITAGE GROUP NEWSLETTER Issue 21 March 2012 October2010 P1 They Lived in Stonehouse

STONEHOUSE HERITAGE GROUP NEWSLETTER Issue 21 March 2012 October2010 P1 They lived in Stonehouse This Issue is about young men who in for him, and on December 1934 start of the following season because were either born or were brought Aston Villa paid £6.500 to secure his of his relationship with the Land- up in our Village of Stonehouse. services. lady of ta Cobbold pub ( The Mull- Some of the following people will be bery Tree )-as a result the Landlord known to some of you, but many will Aston Villa: complained to Captain Cobbold who never have been heard off untill now. The sum of £6.500 was what Villa owned the pub. paid for Jimmy money well spent de- I started to write this article after Ipswich aimed high as they sought scribed in who,’s who of Aston Villa coming across footballer Jimmy a replacement manager, they tried in as a brilliant ball artist and inspiring McLuckie who was born in Stone- vain for Major Frank Buckley who Captain. house and went on to become a top was manager of Wolverhampton class footballer. Ipswich Town: Wanderers at that time. Instead they James McLuckie: The first professional to join Ips- secured Adam Scot Duncan, who was the manager of Manchester United. Born in Stonehouse2nd April 1908 wich Town after the club joined Died November 1986 Aged 78 the Southern League in 1936.Ips- Ipswich Town Wing –half 1936-1939 wich had players such as Charlie Cowie ( later to become reserve Tranent Juniors: team trainer from Barrow) Jack Jimmy started his career with Tranent Blackwell from Boston and Bobby Juniors, Jimmy was originally a left Bruce from Shefield Wednesday. -

A Study of Institutional Racism in Football

THE BALL IS FLAT THE BALL IS FLAT: A STUDY OF INSTITUTIONAL RACISM IN FOOTBALL By ERIC POOL, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Eric Pool, September 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Ball is Flat: A Study ofInstitutional Racism in Football AUTHOR: Eric Pool, B.A. (University of Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor Chandrima Chakraborty NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 127 ii Abstract: This project examines the ways in which the global mobility of players has unsettled the traditional nationalistic structure of football and the anxious responses by specific football institutions as they struggle to protect their respective political and economic hegemonies over the game. My intention is to expose the recent institutional exploitation of football's "cultural power" (Stoddart, Cultural Imperialism 650) and ability to impassion and mobilize the masses in order to maintain traditional concepts of authority and identity. The first chapter of this project will interrogate the exclusionary selection practices of both the Mexican and the English Football Associations. Both institutions promote ethnoracially singular understandings of national identity as a means of escaping disparaging accusations of "artificiality," thereby protecting the purity and prestige of the nation, as well as the profitability of the national brand. The next chapter will then turn its attention to FIFA's proposed 6+5 policy, arguing that the rule is an institutional effort by FIF A to constrain and control the traditional structure of football in order to preserve the profitability of its highly "mediated and commodified spectacle" (Sugden and Tomlinson, Contest 231) as well as assert its authority and autonomy in the global realm. -

Miguel Arturo LAYÚN (2015) Midfielder

Miguel Arturo LAYÚN (2015) Midfielder (Full name Miguel Arturo LAYÚN PRADO) Born Córdoba, Mexico, 25 June 1988 Representative honours Mexico Full Watford Career Football League & FA Premier League: 16+4 appearances (1 goal) Football League Cup: 1 appearance Début: 1-3 away defeat v Huddersfield Town, Football League Championship, 10 Jan 2015 Final game: (as sub) 0-2 away defeat v Manchester City, FA Premier League, 29 Aug 2015 Longest run of consecutive appearances: Football League 11; all competitions 11 Career Path Tiberunes Rojos de Veracruz (Mexico) (2006); Atalanta (Italy) (€625,000 2009); Club América (Mexico) (2010); Granada (Spain) (December 2014); WATFORD (undisclosed fee January 2015); Porto (Portugal) (€500,000 loan September 2015, €6 million permanent transfer July 2016); Sevilla (Spain) (loan January 2018) Football League & FA Premier League Career Apps Subs Goals League Status and Final Position 2014/15 WATFORD 14 3 Football League Championship (2nd tier) – 2nd of 24 (Promoted) 2015/16 WATFORD 2 1 1 FA Premier League – 13th of 20 The first Mexican to play in Italy’s Serie A, Miguel Layún represented his native country as a full-back in the 2014 World Cup Finals, but was used by Watford as an energetic midfielder in the second half of a season in which the club won promotion to the FA Premier League. He then went on to help Mexico win the 2015 CONCACAF Gold Cup, in which Adrian Mariappa and Jobi McAnuff were in the Jamaica side that was beaten in the Final. Layún is descended from grandfathers of Lebanese and Spanish nationality, respectively. ****Watford will get 20 per cent if he is sold by Porto for a fee exceeding €6.5 million*** Lebanese paternal grandfather, Spanish maternal grandfather.