The Stanley Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middlesbrough Edition

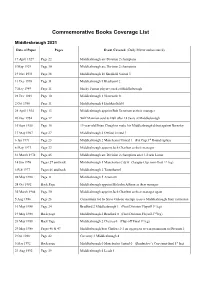

Commemorative Books Coverage List Middlesbrough 2021 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 17 April 1927 Page 22 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions 5 May 1929 Page 30 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions 19 Nov 1933 Page 38 Middlesbrough 10 Sheffield United 3 11 Dec 1938 Page 31 Middlesbrough 9 Blackpool 2 7 May 1949 Page 11 Micky Fenton player-coach at Middlesbrough 28 Dec 1949 Page 10 Middlesbrough 1 Newcastle 0 2 Oct 1950 Page 11 Middlesbrough 8 Huddersfield 0 28 April 1954 Page 13 Middlesbrough appoint Bob Dennison as their manager 26 Dec 1954 Page 17 Wilf Mannion sold to Hull after 18 years at Middlesbrough 16 Sept 1955 Page 16 19 year-old Brian Clough to make his Middlesbrough debut against Barnsley 17 May 1967 Page 27 Middlesbrough 4 Oxford United 1 6 Jan 1971 Page 23 Middlesbrough 2 Manchester United 1 (FA Cup 3rd Round replay) 8 May 1973 Page 32 Middlesbrough appoint Jack Charlton as their manager 31 March 1974 Page 45 Middlesbrough are Division 2 champions after 1-0 win Luton 14 Jan 1976 Pages 27 and back Middlesbrough 1 Manchester City 0 (League Cup semi-final 1st leg) 6 Feb 1977 Pages 46 and back Middlesbrough 2 Tottenham 0 20 May 1980 Page 31 Middlesbrough 5 Arsenal 0 24 Oct 1982 Back Page Middlesbrough appoint Malcolm Allison as their manager 30 March 1984 Page 30 Middlesbrough appoint Jack Charlton as their manager again 5 Aug 1986 Page 26 Consortium led by Steve Gibson attempt to save Middlesbrough from extinction 16 May 1988 Page 24 Bradford 2 Middlesbrough 1 (First Division Playoff 1st -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

La Leyenda De Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 Pie Izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney Siempre Fue Un Talento Incontro- Enero

JUGADORES GOLES 53de cabeza11 ROONEY, CON MÁS PARTIDOS Ganados 1970-90 PARTIDOS 119 1º Peter Shilton125 71 Empatados 5 2003-17 29 la leyenda de Inglaterra 2º Wayne Rooney119 Perdidos 37 pie izquierdo 1996-09 19 Rooney siempre fue un talento incontro- enero. "Se merece estar en los libros de 3º David Beckham pie derecho Probablemente, Rooney 115 lable. Su expulsión en los cuartos del historia del club. Estoy seguro de que ROONEY está entre los 10 mejores futbolistas Mundial de 2006 ante Portugal por su anotará muchos más", armó Sir Alex ingleses de la historia. Su carrera es trifulca con Cristiano aún retumba en las Ferguson, el técnico que le llevó al 4º Steve Gerrard2000-14 maravillosa. Islas. Jugó tres Copas del Mundo (2006, United. 114 2010 y 2014) y tres Euros (2004, 2012 y Después de ganar 14 títulos en Old Gary Lineker 2016) sin suerte. Siete goles en 21 Traord, 'Wazza' ha vuelto 13 años partidos de fases nales, 37 en 74 después a casa, al Everton, para apurar 5º Bobby Moore1962-73 Del 12 de febrero de 2003, cuando debutó encuentros ociales y 16 en 45 amistosos su carrera. Y en Goodison Park ha 108 con Inglaterra en un amistoso ante son el baje del jugador de campo con aumentado su mito anotando dos tantos Australia con 17 años y 111 días, a su más duelos y más victorias (71) de la en dos jornadas de liga inglesa que le último duelo, el 11 de noviembre de 2016 historia de Inglaterra al que han llegado disparan a los 200 goles en Premier. -

Advanced Information

Title information Stoke City Minute By Minute Covering More Than 500 Goals, Penalties, Red Cards and Other Intriguing Facts By Simon Lowe Key features • Fascinating look back at Stoke City’s most important moments and greatest goals – with the times, dates and descriptions of how they hit the net • First book of its kind on the Potters, with hundreds of memorable moments revisited • A treasure trove of nostalgia for Stoke City fans, charting the club's proud history with all the drama, elation, heartache, highs and lows • Revisits the goals scored by club legends of various eras – including Freddie Steele, Jimmy Greenhoff, John Ritchie, Mark Chamberlain, Mark Stein, Mike Sheron, Peter Thorne, Ricardo Fuller, Jon Walters and Peter Crouch • Publicity campaign planned including radio, newspapers, websites, podcasts and magazines Description Stoke City: Minute by Minute takes you on a tumultuous journey through the Potters’ remarkable history. Relive all the breathtaking goals, heroic penalty saves, Wembley wins, game-changing incidents, sending offs and other memorable moments in this unique by-the-clock guide. From the glory days of Stanley Matthews, the celebrated Tony Waddington era, Lou Macari’s beloved team, Tony Pulis’s promotion to the Premier League and Mark Hughes’s ‘Stokealona’ side, this book covers everything. Featuring goals from Freddie Steele, Jimmy Greenhoff, John Ritchie, Mark Chamberlain, Mark Stein, Mike Sheron, Peter Thorne, Ricardo Fuller and Peter Crouch, plus countless others – the book is crammed with thrilling memories from kick-off through to the final whistle. Revisit the Potters’ most spectacular modern feats and learn things you didn't know about the club’s incredible past – from goals scored in the opening seconds to those last-gasp, extra-time winners that have thrilled generations of fans at the Victoria Ground and Bet365 Stadium. -

Supporters Guide Preston North End Fc

PRESTON NORTH END FC PP SUPPORTERS GUIDE PNEFC, SIR TOM FINNEY WAY, DEEPDALE, PRESTON PR1 6RU WWW.PNE.COM WWW.MYPNE.COM 0344 856 1964 [email protected] PRESTON NORTH END FC WELCOME TO DEEPDALE GETTING TO KNOW US Welcome to Deepdale – the home of Preston North End Football Club, also known as the Lilywhites! Established in 1880, we are proud to be one of the founder members of the EFL and the first team to ever achieve the double, winning the league and the FA Cup in the first league season in 1888. This memorable season also saw North End go unbeaten in the league and the FA Cup, giving us the famous title ‘The Invincibles’. In recent years, North End were crowned third division champions in 1996 and second division champions in 2000. After nine Play-Off attempts across the second, third and fourth tiers, the Lilywhites secured victory at Wembley in 2015, back into the Championship. Several notable players have played for Preston North End over the years, including England legend Sir Tom Finney, Scottish defender and future Liverpool legend, Bill Shankly and the club’s record appearance maker and Republic of Ireland international goalkeeper, Alan Kelly senior. Modern heroes have included David Moyes, Kevin Kilbane, David Nugent and even England’s record outfield appearance maker and global superstar David Beckham! Simon Grayson is currently the manager looking to guide the Lilywhites to a second promotion under his reign, this time to the Premier League. Simon has been at the club since 2013, having previously managed Blackpool, Leeds United and Huddersfield Town. -

Remember When Tuesday, September 10, 2019

10 Remember When Tuesday, September 10, 2019 Wilf’s Football League ‘100 TRIBUTE TO ‘MOZART OF FOOTBALL’ Legends’ medal. Picture: Middlesbrough FC Golden Boy was a diamond for Boro In our latest feature marking 25 years since the last season at Ayresome Park, Manchester Metropolitan University historian Dr Tosh Warwick explores memories of arguably the greatest Boro player of the Ayresome era… YRESOME Park played host to many great players and famous names over the decades. Yet for many, one name stands out: Wilf Mannion. AThe diminutive inside-forward, born in South Bank, was truly a great of the game and regarded as one of, if not the, greatest Boro players of the Ayre- some era. Mannion’s story of wowing the footballing world on an international stage for England and Great Britain, and his infa- mous contract dispute with Middlesbrough that saw the man Stanley Matthews dubbed ‘the Mozart of Football’ spend a year out of the game, is worthy of several books to go, along- side Nick Varley’s excellent Golden Boy biography. A delve into the collections of Teesside Archives helps pro- vide first-hand accounts from those who saw Mannion play in his prime at Ayresome Park in the 1930s and 1940s, as Mid- dlesbrough fleetingly threat- ened to upset the hierarchies of British football, alongside the likes of George Camsell and George Hardwick. Middlesbrough FC’s collec- tions also help shed light on the star’s career when the boy from Lower Napier Street in uted, many inevitably reference his later Wilf play for a season and a South Bank penned a profes- days at Boro and life after football working half. -

1 Monkey Glands and the Major: Frank Buckley and Modern Football

1 Monkey Glands and The Major: Frank Buckley and modern football management Introduction On 22 December 1964, the main headline on the back page of the Wolverhampton Express and Star read simply, „The Major is Dead‟. For the paper‟s readers no further explanation was deemed necessary. Frank Buckley had been the manager of Wolverhampton Wanderers from 1927 to 1944. During this period, Wolves had become one of the most feared and respected teams in the country. However, during this time he never won a trophy, although Wolves did nearly win the Double in 1939. Indeed, the Golden Era of Wolves was in the 1950s under one of his protégés, Stan Cullis. Yet it is clear, that over 20 years after he left Wolves, Buckley‟s presence and his legacy was still firmly fixed in the memories of the fans of Wolves and of the people of Wolverhampton in general. In addition, in The Times, together with two internationally renowned scientists and an important Scotland Yard policeman, there was also an obituary for Buckley. This was significant for a number of reasons. First, it reflected football‟s position as the national game. It also highlighted not only the importance now ascribed to the position of the manager within football but also its growing visibility within popular culture more generally. And of course, it illustrated the importance of Buckley himself. Percy Young has stated that „Modern [football] management is based largely on the pioneer work of [Herbert] Chapman and Buckley‟.i In The Times obituary, Buckley was described amongst other things as „a pioneer in modern training methods‟ and someone who had „an uncommon flair for public relations‟.ii So, why was he considered such an important figure within football and in what context did his managerial career develop? Frank Buckley – A Sporting Life 2 First, while this essay is mainly concerned with Buckley‟s career at Wolverhampton Wanderers, it would useful to provide some brief background to this main focus. -

View the Text of Geoff Maitland's Presidential Address

1 Chemical engineering matters everywhere - reflections on a journey from academe to industry, and back again Institution of Chemical Engineers Presidential Address, May 28th 2014 Professor Geoffrey Maitland FREng FIChemE 1. Introduction How did I come to be standing here? I think it was John Lennon who once observed that life is what happens when you are planning something else – I know exactly what he was talking about. For the last nine years I have been professor of energy engineering at Imperial College London, carrying out research with my students and colleagues, many of whom are here tonight, on a variety of topics right across the energy landscape, from clean fossil fuels to green algae as a source of renewable hydrogen. To explain how I came to this life of engineering and to be working on what I consider to be probably the most important challenge facing the world in this 21st Century, I want to take you all on a journey, which began in Stoke-on-Trent in the 1940’s, and tell you about some of the doors that opened up along the way. And I want to use this journey to comment on some of the challenges and opportunities for chemical engineers today and what I would like to achieve for the Institution and our profession as your President. 2. Early beginnings… a first taste of Engineering As Dylan Thomas said, “To begin at the beginning…” I was born in Stoke, the Potteries, so you will not be surprised to learn that my father worked in the pottery industry, at a company called Podmore and Sons. -

Sample Download

THE HISTORYHISTORYOF FOOTBALLFOOTBALL IN MINUTES 90 (PLUS EXTRA TIME) BEN JONES AND GARETH THOMAS THE FOOTBALL HISTORY BOYS Contents Introduction . 12 1 . Nándor Hidegkuti opens the scoring at Wembley (1953) 17 2 . Dennis Viollet puts Manchester United ahead in Belgrade (1958) . 20 3 . Gaztelu help brings Basque back to life (1976) . 22 4 . Wayne Rooney scores early against Iceland (2016) . 24. 5 . Brian Deane scores the Premier League’s first goal (1992) 27 6 . The FA Cup semi-final is abandoned at Hillsborough (1989) . 30. 7 . Cristiano Ronaldo completes a full 90 (2014) . 33. 8 . Christine Sinclair opens her international account (2000) . 35 . 9 . Play is stopped in Nantes to pay tribute to Emiliano Sala (2019) . 38. 10 . Xavi sets in motion one of football’s greatest team performances (2010) . 40. 11 . Roger Hunt begins the goal-rush on Match of the Day (1964) . 42. 12 . Ted Drake makes it 3-0 to England at the Battle of Highbury (1934) . 45 13 . Trevor Brooking wins it for the underdogs (1980) . 48 14 . Alfredo Di Stéfano scores for Real Madrid in the first European Cup Final (1956) . 50. 15 . The first FA Cup Final goal (1872) . 52 . 16 . Carli Lloyd completes a World Cup Final hat-trick from the halfway line (2015) . 55 17 . The first goal scored in the Champions League (1992) . 57 . 18 . Helmut Rahn equalises for West Germany in the Miracle of Bern (1954) . 60 19 . Lucien Laurent scores the first World Cup goal (1930) . 63 . 20 . Michelle Akers opens the scoring in the first Women’s World Cup Final (1991) . -

Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3

Felly’s Football Tour Sprint/Summer 2021 (tbc) Fundraising for Fellysfund in memory of our good friend The Motivation To Turf Moor To the University of Bolton Stadium Supporting Felly’s Fund To Deepdale To Goodison Park To Boundary Park Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3 Redwood Events have been arranging charity walks and cycle events since 2007 and have recently started to work with the Darby Rimmer MND Foundation. This has given us a great exposure to, and understanding of, the challenges that the Motor Neurone Disease can bring. Life changes very quickly for those diagnosed with MND and for their families. The average life expectancy for someone with Motor Neurone Disease is just 2-5 years from the onset of symptoms. A third of people diagnosed will die within a year and half within 2 years. It’s a 1/300 lifetime risk in the UK of being diagnosed with MND. That’s 3 children in each and every school today. There is no known cause of MND and there is no cure or effective treatment, it’s always fatal. When Paul Stanway talked to us about the great work they have done in memory of their great friend Felly, we were very keen to help. Felly’s Football Tour will combine a 131 mile continuous walking tour from Liverpool FC (Felly’s favourite team) to Fleetwood Town FC calling at fifteen other football grounds in between. This is a journey of 130 miles. After a short break for breakfast, the walking will give to cycling as riders will then head north from Fleetwood Town to Barrow AFC via Morecambe FC, a journey of 73 miles. -

Sample Download

Contents Acknowledgements 10 1. Junk, Historical Objects and Magical Memories 13 2 Hard Times 38 3. Schoolboy Dreams 59 4. Light at the End of the Tunnel 77 5. Soccer Diaries 104 6 You’ve Never Had It So Good 129 7. Bovril or Boutiques? 157 8. World Cup Winners 182 9. Scotland 207 10. Sponsors, Violence and Economic Crisis 229 11. A Slum Game 264 12. Foreign Fields 296 13. From the Terraces to the World- Wide Sofa 320 14. Wartime to Lockdown 353 Bibliography 372 Index of Clubs, Managers and Players 374 Chapter 1 Junk, Historical Objects and Magical Memories SOME BOOKS inspired by football memorabilia tell the story of men undergoing a mid-life crisis, steeped in nostalgia for the 1980s They chart the journey from naive nerd, standing on the terraces with laddish mates, and then with a succession of girlfriends who, with varying degrees of disinterest, observed the on-field displays of their temporarily beloved’s heroes Punk rock provides the mood music to the occasional brush with the National Front or opposition casuals Marriage, divorce and contentment with a second wife follow, as our protagonist takes his seat in the stands with a nostalgic sigh for a youth now lost forever This book is different Yes, it intertwines my own life as one of the now grey-haired ‘baby boomer’ generation with the changes within the game, but – spoiler alert – that life, while not uneventful, has not been punctuated by multiple liaisons More than 50 years of marriage to the same woman, while cherished, is a thin basis for dramatic shifts of plot The sum -

Wall Art Catalogue

R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES World Landmarks Rio De Janeiro Colloseum Eiffel Tower Sydney Opera House Burj Khalifa Taj Mahal Hollywood Statue of Liberty Golden Gate Bridge Niagara Falls Tower of Pisa Pyramids R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES World Landmarks Chichen Itza Bryce Canyon Table Mountain Greek Temple Great Wall of China Lost Temple City Gibraltar Rock R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES UK Landmarks Westminster Tower Bridge Buckingham Palace Changing of the Guards Blackpool Tower Leeds Castle Yorkminster Name of Wallpaper Clifton Suspension Bridge Needles White Cliff Giants Causeway R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES UK Landmarks Stonehenge Millenium Stadium (Outside) Millenium Stadium (Inside) Tyne Bridge Angel of the North Glasgow Clyde Stirling Castle Edinburgh Castle Wallace Monument Forth Road Bridge Forth Rail Bridge R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES Holiday Destinations Aberystwyth Blackpool Pier Blackpool Tower Bournemouth Brighton Pier Brighton Pier 2 Brighton Cornwall Cornwall 2 Devon Beach Dorset Cliffs Eastbourne R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES Holiday Destinations Isle of Skye Isle of Skye 2 Isle of Wight Isle of Wight 2 Isle of Wight 3 Norfolk Broads Norfolk Broads 2 North Wales Oban Paignton Beach Scarborough Scarborough Beach R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES Holiday Destinations Seven Sisters South Wales Southend-on-Sea Southport St Andrews Tobermory Torquay Busy Beach R R E E C C O O G G N N EYES Wall Art EYES Holidays Holidays (1) Holidays