Transforming Legal Aid: Next Steps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inventory of Literature on the Relation Between Drug Use, Impaired Driving and Traffic Accidents

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre on Drug Use E.M.C.D.D.A. DRUGS MISUSE RESEARCH DIVISION HEALTH RESEARCH BOARD An Inventory of Literature on the Relation between Drug Use, Impaired Driving and Traffic Accidents CT.97.EP.14 Research Team: Colin Gemmell Trinity College, Dublin Rosalyn Moran Drugs Misuse Research Division, Health Research Board James Crowley Professor, Transport Policy Research Institute, University College Dublin Richeal Courtney Medical Expert, for the Health Research Board EMCDDA: Lucas Wiessing February 1999 Please use the following citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. An Inventory of Literature on the Relation betweenDrug Use, Impaired Driving and Traffic Accidents. (CT.97.EP.14) Lisbon: EMCDDA, February 1999. Contact Details Drugs Misuse Research Division Health Research Board 73 Lower Baggot Street Dublin 2 Ireland European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Rua Cruz de Santa Apolónia 23/25 1100, Lisboa Portugal. Further copies of this bibliography can be obtained from the EMCDDA at the above address. CREDITS Principal Researchers Ms Rosalyn Moran, Project Leader, Health Research Board Professor James Crowley, Professor, Transport Policy Research Institute, UCD Dr Richeal Courtney, Medical Expert, on behalf of the Health Research Board Research Assistants Colin Gemmell (Synthesis and Final Reports) Sarah Heywood (Literature Search and Collaborative Network) For the EMCDDA Lucas Wiessing -

Author and Keyword Index

AUTHOR AND KEYWORD INDEX Author Index Abadie, J. P1 Abraham,T. P47 Afzal, M. S53 Agrawal, A. S3 Agrawal, A. S5 Alexander, R. S32 Allan, C. P22 Anderson, D. P18 Andollol, W. P14 Andrew,T. S41 Anne, L P56 Avella, J. S46 Averin, O. P27 Ayres, P. P23 Backer, R. P6 Ballesteros, S. S25 Balraj, E. S41 Bankson, D. P1 Barnes, A. P47 Barnes, A. P39 Barnes, A. P35 Barnes, A. P32 Barry, M. S32 Baylor, M. P33 Baylor, M. P34 Behonick, G. S39 Bell, S. P50 Benoit, M. S16 Benski, L. P43 Bih, C. P56 Blackwell, W. P43 Blackwell, W. S10 Blum, K. P53 Bodepudi, V. P56 Boehme, D. S49 Borges, C. P58 Bramlett, R. P42 Briglia, E. S46 Bultman, S. P29 Burbach, C. P23 Bush, D. P33 Bush, D. P34 Bynum, N. S23 Callery, P. P41 Callery, P. S51 Callery, P. P50 Callery, R. S12 Capian, Y. S7 Cardona, P. S36 Carr, P. S37 Chao, O. S48 Chaplinsky, L P5 Chaturverdi, A. S36 Chechlacz, R. P12 Cheng, P. S52 Chmara, E. P19 Choo, R. P40 Chronister, C. P26 Cibull, D. P9 Clarke, J. P53 Clay, D. S51 Cochems, A. S44 Cochems, A. S11 Cody, J. P54 Cody, R. S38 Cody, R. P38 Colona, K. P4 Cone, E. P32 Cone, E. P39 Cone, E. P35 Cone, E. S7 Cone, E. S34 Cone, E. P55 Conoley, M. P44 Conoley, M. P15 Couper, F. S41 Cox, D. S21 Cox, D. P30 Coy, D. P5 Crook, D. S9 Crouch, D. P58 Dahn, T. P51 Darwin, W. P55 Datuin, M. P56 Day, D S4 Day, J. -

THE CIRCUITEER Issue 43 / July 2017 1 News from the South Eastern Circuit EDITOR’S COLUMN

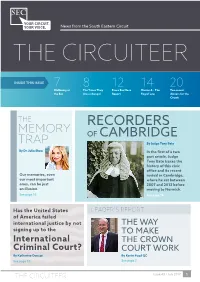

News from the South Eastern Circuit THE CIRCUITEER INSIDE THIS ISSUE 7 8 12 14 20 Wellbeing at The Times They Essex Bar Mess Marine A – The Two recent the Bar Are a-changin’ Report Fog of Law dinners for the Circuit THE RECORDERS MEMORY OF CAMBRIDGE TRAP By Judge Tony Bate By Dr. Julia Shaw In the first of a two part article, Judge Tony Bate traces the history of this civic office and its recent Our memories, even revival in Cambridge, our most important where he sat between ones, can be just 2007 and 2013 before an illusion. moving to Norwich. See page 10 See page 16 Has the United States LEADER’S REPORT of America failed international justice by not THE WAY signing up to the TO MAKE International THE CROWN Criminal Court? COURT WORK By Katherine Duncan By Kerim Fuad QC See page 13 See page 3 THE CIRCUITEER Issue 43 / July 2017 1 News from the South Eastern Circuit EDITOR’S COLUMN Karim Khalil QC type this looking out over expended on trying to confront Cambridge. No doubt there are an unusually sunny London and improve the GFS in criminal similarly fascinating pockets Iday as the Pride March brings cases only to find that the of knowledge across the much-needed colour and joy Government surrendered its Circuit, so let no Judge keep to a beleaguered city. This majority position and with their pen dry … seems to chime tunefully with it the Lord Chancellor … we As ever, we extend a very warm the increasing awareness of can only lend our continuing welcome the many recent the importance of tolerance support to those who work appointments and hope that and support for all, as Wellness on our behalves to try and re- the fabulous parties held in at the Bar and elsewhere kindle the discussions, perhaps celebration are matched by is taking central stage for invigorated by the news of the continued success. -

Oliver Glasgow QC

Oliver Glasgow QC "He is a rising star of the future." Chambers UK 2016 Year of Call: 1995 QC: 2016 020 7353 5324 Oliver Glasgow is appointed as Senior Treasury Counsel and on the Attorney-General’s list of approved counsel. He has a reputation for detailed preparation, exceptional advocacy and is “an especially good cross-examiner”. He is recommended in the top band of leading juniors by the Chambers UK and the Legal 500. “A very careful, strong persuasive advocate in writing and on his feet.” – Legal 500, 2015. He divides his practice between working at the highest level in the criminal sphere and specialising in complicated and serious quasi-criminal and regulatory work. He appears on behalf of the major prosecuting authorities in high profile trials of the utmost gravity and his work has won the plaudits of judges and opponents alike. He defends in regulatory and health and safety cases, and acts for interested parties in public inquiries and inquests where his advocacy skills have marked him out as “something special”. “He is hard-working, diligent and committed.”- Chambers UK 2016 “A standout junior.” Legal 500, 2014 “Commercial, hard working and very approachable.” Chambers UK “Oliver Glasgow courts high market esteem as one of the best juniors in the field” Chambers UK 2012 Location Contact Us 2 Hare Court T: +44 (0)20 7353 5324 Temple F: +44 (0)20 7353 0667 London E: [email protected] EC4Y 7BH DX: LDE 444 Chancery Lane “Sources value his impressive knowledge of sports law, as well as his evident prowess on the criminal side.” Chambers UK Criminal Prosecution - Public In serious and organised crime his areas of expertise include, murder, firearms and terrorism. -

Brexit: to IP Completion Day and Beyond

Brexit: to IP Completion Day and Beyond Mark Phillips QC on whether British Virgin Islands: Litigation Funding the UK will be flying, or at A liquidator’s year in Insolvency Harneys BVI’s Andrew Stefanie Wilkins least falling, with style Thorp and Peter Ferrer and Burford Capital’s on an important year Robin Ganguly take for liquidators a global look at litigation funding A regular review of news, cases and www.southsquare.com articles from South Square barristers ‘The set is highly regarded internationally, with barristers regularly Chambers UK Bar Awards, winner 2019 appearing in courts CHAMBERS BAR AWARDS around the world.’ Chambers/Insolvency set of the year 2019 CHAMBERS UK CHAMBERS & PARTNERS +44 (0)20 7696 9900 | [email protected] | www.southsquare.com Contents 3 In this issue 06 14 18 Brexit: British Virgin Islands: Litigation Funding in Insolvency to IP Completion Day and Beyond A liquidator’s year Stefanie Wilkins and Burford Capital’s Mark Phillips QC on whether the UK Harneys BVI’s Andrew Thorp and Robin Ganguly on litigation funding will be flying, or a least falling, Peter Ferrer on an important year with style for liquidators ARTICLES REGULARS The Honourable Frank J C 23 From the Editors 04 South Square/RISA 56 Newbould QC News in Brief 64 Cayman Conference Chambers is delighted to welcome Diary Dates 68 our newest Associate Member Euroland 58 South Square Challenge 70 Associate Member Professor Cryptoassets, cryptocurrencies 24 Christoph Paulus on CASE DIGESTS and insolvency developments on the continent -

Christopher Ware

Christopher Ware "A polished performer who offers great insight into a case. He is erudite and articulate and will roll up his sleeves and get into the detail when required." "Chris is very bright, extremely efficient and great fun to work with." Chambers UK 2021 Year of Call: 2007 020 7353 5324 Christopher Ware principally defends in serious and complex fraud; corporate, regulatory and business crime; and high-profile and serious crime. He has acted in prosecutions involving, for example, multi-million pound company internal investigations, allegations of bribery and corruption, money laundering, insider dealing, ‘boiler room’ fraud, perjury, perverting the course of justice, and trading standards offences. Christopher also acts in regulatory proceedings and sports law, including involving such bodies as the Football Association and the British Horseracing Authority. He has been instructed on cases including match-fixing and corruption related issues, betting, and on field conduct. Christopher has been instructed in a number of high profile cases including: Ben O’Driscoll & others (Operation Elveden, allegations of corruption by journalists; one of the largest and most costly police investigations in criminal history. Acted for a deputy Editor of The Sun); Greig Box-Turnbull & others (Operation Elveden, represented a reporter at the Daily Mirror); Ben Ashford (Operation Tuleta, acted for a reporter at The Sun. Allegation of computer hacking by journalists); Operation Yewtree (represented well-known individual in High Court proceedings. High-profile, long-running investigation into historical abuse); Operation Cotton (multi-million pound land banking fraud, FCA prosecution); Operation Citrus (represented company director in multi-million pound trading standards and fraud prosecution, said to be first trading standards prosecution of its kind); Operation Tabernula (pre-charge advice to the FCA, largest ever insider dealing investigation); Operation Callahan (represented senior employee, multi-million pound telecommunications fraud). -

CHUDASAMA Applicant - and - the QUEEN Respondent

Neutral Citation Number: [2018] EWCA Crim 2867 Case No: 201801705A2 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CRIMINAL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT Her Honour Judge Joseph QC T20187026 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 21/12/2018 Before : THE PRESIDENT OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION (SIR BRIAN LEVESON) MRS JUSTICE WHIPPLE DBE and MRS JUSTICE CHEEMA-GRUBB DBE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : JAYNESH CHUDASAMA Applicant - and - THE QUEEN Respondent - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Leila Gaskin (instructed by JSP Law) for the Applicant Oliver Glasgow QC (instructed by Crown Prosecution Service) for the Crown Hearing date : 4 December 2018 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Approved by the court for handing down (subject to editorial corrections) If this Judgment has been emailed to you it is to be treated as ‘read-only’. You should send any suggested amendments as a separate Word document. Sir Brian Leveson P : 1. On 26 February 2018, at the Central Criminal Court before Her Honour Judge Joseph QC, the applicant (who is now 29 years of age) pleaded guilty to three offences of causing death by dangerous driving. On 28 March 2018, he was sentenced by the Judge to 13 years’ imprisonment on each count, the sentences to run concurrently. He was also disqualified from holding or obtaining a driving licence for 13½ years and, thereafter, until he passed an extended driving test. In addition, a Victim Surcharge Order was made. His application for leave to appeal against sentence has been referred to the full court by the Registrar. The Facts 2. This summary of the facts is taken from the way in which the case was opened before the Judge. -

Oliver Glasgow QC

Oliver Glasgow QC "Polished and highly intelligent, he is simply one of the best prosecutors around. Master of his brief and a deadly cross-examiner. Mr Glasgow is very approachable, decisive and always dealt with the cases to the highest standard. He's an excellent advocate, concentrates on the issues in the case and engages well with other court users." Legal 500 UK 2021 Year of Call: 1995 QC: 2016 020 7353 5324 Appointed in 2021 as First Senior Treasury Counsel and on the Attorney-General’s list of approved counsel. He has a reputation for detailed preparation, exceptional advocacy and is “an especially good cross-examiner”. He is recommended in the top band of new silks in the Chambers UK Guide and the Legal 500. He divides his practice between working at the highest level in the criminal sphere and specialising in complicated and serious quasi-criminal and regulatory work. He appears on behalf of the major prosecuting authorities in high profile trials of the utmost gravity and his work has won the plaudits of judges and opponents alike. He defends in regulatory and health and safety cases, and acts for interested parties in public inquiries and inquests where his advocacy skills have marked him out as “something special”. He advises and acts for individuals and companies alike on all aspects of business crime and regulation. Oliver accepts Direct Access instructions. What others say: “A class act” and “an incredibly courageous advocate.” – Chambers UK 2021 “An immaculate prosecutor.” “His work rate is phenomenal. He turns papers -

GOSPEL in CHINA Presbyterian Church of England

No. 600 MARCH, 1896 Price One Penny THE GOSPEL in CHINA Presbyterian Church of England CONTENTS. CALENDAR ........................................... _ _ ... 53 HOME MISSION COLLECTION........................................... 53 FROM MONTH TO MONTH ... ... ._ ............ 53 READINGS IN PRACTICAL RELIGION ...................... 55 HOME BIBLE READINGS.................................................... 56 OUR OWN MISSIONS— Current Notes............................................................ ... 57 The Amoy Work: A Visitor’s Impressions ............. 58 Formosa : Southern Stations........................................... 59 Wukingpoo : NewH ospital (Two Illustrations).............. 60 Engohhun ................................ 60 Chinohew ............ ... ........................................... 62 Changpoo .......................................... 62 Our Students anD Our Foreign Missions ... ... 62 ARAMAIC VILLAGE IN THE ANTI-LEBANON ............ 63 (Three Illustrations) SKETCHES FROM OUR TOWN ...................... «= CHILDREN’S PORTION .............................. 67 NEW BOOKS ........................................... «7 CHURCH TALK.......................................... 60 50 ADVERTISEMENTS A Wonderful Medicine. BEECHAM’S PILLS ARM UNIVERSALLY ADMITTED TO Bl WORTH A GUINEA A BOX Beecham’s Pills. for Bilious and Nervous Disorders, such as Wind and Beecham’s Pills. Pain in the Stomach, Sick Headache, Giddiness, Ful- ness and Swelling after Meals, Dizziness and Drow Beecham’s Pills. siness, Cold Chills, Flushings of -

EWCA Crim 342 No: 2013/6540/A4 in the COURT of APPEAL CRIMINAL DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand London, WC2A 2LL

Neutral Citation Number: [2014] EWCA Crim 342 No: 2013/6540/A4 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand London, WC2A 2LL Friday, 14 February 2014 B e f o r e: LADY JUSTICE RAFFERTY DBE MR JUSTICE COLLINS THE COMMON SERJEANT (His Honour Judge Hilliard QC) (Sitting as a Judge of the CACD) REFERENCE BY THE ATTORNEY GENERAL UNDER S.36 OF THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE ACT 1988 ATTORNEY-GENERAL'S REFERENCE NO 80 OF 2013 Computer Aided Transcript of the Stenograph Notes of WordWave International Limited A Merrill Communications Company 165 Fleet Street London EC4A 2DY Tel No: 020 7404 1400 Fax No: 020 7831 8838 (Official Shorthand Writers to the Court) Mr Oliver Glasgow appeared on behalf of the Attorney General Mr Thom Dyke appeared on behalf of the Offender J U D G M E N T (Approved) Crown copyright© 1. LADY JUSTICE RAFFERTY: Her Majesty's Attorney General in reliance upon the provisions of section 36 Criminal Justice Act 1988 seeks leave to challenge as unduly lenient a sentence imposed on RM. We give leave. 2. M, 68, born on 23rd March 1945, on 2nd December 2013 was sentenced after conviction by a jury as follows: On counts 1 and 2, indecent assaults on his stepdaughter S when she was between 8 and 9, contrary to section 14 Sexual Offences Act 1956 two years' imprisonment on each; on counts 3 and 4, sexual activity with S when she was between 9 and 11, contrary to section 9 Sexual Offences Act 2003 three years' imprisonment on each; and counts 5 and 6 like offences when S was between 11 and 13 four-and-a-half years' imprisonment on each, all the terms concurrent, the total four-and-a-half years. -

Al Sadd Overcome Hienghene in Opener

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Pages 8 Ancelotti’s reign ends amid Qatar Airways among feuding as airlines committed to Napoli turn ‘25by2025’ campaign to Gattuso published in QATAR since 1978 THURSDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11394 December 12, 2019 Rabia II 15, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets Italian envoy In brief Al Sadd overcome PM attends announcement Hienghene in opener of new cloud datacentre region FIFA Club World Cup the FIFA Club World Cup Qatar 2019 time when Amy Roine drew level. With HE the Prime Minister and kicked off yesterday. Sadd players spurning chance after Interior Minister Sheikh Abdullah Qatar 2019 kicks off At the Jassim Bin Hamad Stadi- chance, the game went into 30-minute bin Nasser bin Khalifa al-Thani um, Sadd needed extra time to beat extra time, where Abdelkarim Hassan yesterday attended a ceremony By Sahan Bidappa Oceania winners Hienghene to seal scored after a howler from Hiengh- to announce the setting up of a Doha a place in the quarter-fi nals against ene goalkeeper Rocky Nyikeine, be- new cloud datacentre region in Mexican side Monterrey. fore Pedro Miguel relieved pressure on Qatar, jointly by the Ministry of Sadd looked for a comfortable win coach Xavi Hernandez with a strike in Transport and Communications spirited Hienghene Sport gave when Baghdad Bounedjah put them in the 114th minute. and Microsoft. The initiative seeks Al Sadd a scare before the hosts front in the 26th minute, but Hieng- Qatar league champions Sadd have to deliver Microsoft’s intelligent, A won 3-1 in a play-off match as hene hit back immediately after half not been at their best form, having lost trusted cloud services and three of their last four league matches. -

Burns Chronicle 1946

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1946 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Schiehallion Scottish Heritage Society The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com THE ROBERT BURNS ANNUAL AND CHRONICLE 1946 THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK Price : in paper wrapper, 2 /6 ; in cloth, 4/- (To members of federated clubs: in paper wrapper, 2 /-; in cloth, 3 /6) "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER SCOTTISH OATMEAL baked under ideal conditions . 'CRIMPIE' OATCAKES by WYLLIE, BARR & ROSS LTD. at the Sunshine Biscuit Bakery 2· "BURNS CHRONICLE.,. ADVERTISER KILMARNOCK BURNS MONUMENT, Statue, Library, and Museum. 'fms valuable and unique collection has been visited by thousands from all parts of the World. A veritable shrine of the "Immortal Bard." The Monument occupies a commanding position in the Kay Park. From the top a most extensive and interesting view of the surrounding Land of Burns can be obtained. The Magnificent Marble Statue of the Poet, from the chisel of W. G. Stevenson, A.R.S.A., Edinburgh, is admitted to be the finest in the World. The Museum contains many relics an,d mementoes of the Poet's life, and a most valuable and interesting collection of his original MSS., among which are the following :- Tam o' Shanter. The Death e.nd Dying Words Cotter's Saturday Night. o' Poor Maille•. The Twa Dogs. Lassie wt' the Lint-white The Hol7 Fair. Locks. Address to the Dell. Last May a Braw Wooer cam John Barle7corn.