The Context of REDD+ in Brazil Drivers, Agents and Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icthyofauna from Streams of Barro Alto and Niquelândia, Upper Tocantins River Basin, Goiás State, Brazil

Icthyofauna from streams of Barro Alto and Niquelândia, upper Tocantins River Basin, Goiás State, Brazil THIAGO B VIEIRA¹*, LUCIANO C LAJOVICK², CAIO STUART3 & ROGÉRIO P BASTOS4 ¹ Laboratório de Ictiologia de Altamira, Universidade Federal do Para – LIA UFPA e Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biodiversidade e Conservação – PPGBC, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), Campus Altamira. Rua Coronel José Porfírio 2515, São Sebastião, Altamira, PA. CEP 68372-040, Brasil; [email protected] ² Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Evolução, Departamento de Ecologia, ICB, UFG, Caixa postal 131, Goiânia, GO, Brasil, CEP 74001-970. [email protected] 3 Instituto de Pesquisas Ambientais e Ações IPAAC Rua 34 qd a24 Lt 21a Jardim Goiás Goiânia - Goiás CEP 74805-370. [email protected] 4 Laboratório de Herpetologia e Comportamento Animal, Departamento de Ecologia, ICB, UFG, Caixa postal 131, Goiânia, GO, Brasil, CEP 74001-970. [email protected] *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: In face of the accelerated degradation of streams located within the Brazilian Cerrado, the knowledge of distribution patterns is very important to aid conservation strategies. The aim of this work is to increase the knowledge of the stream’s fish fauna in the State of Goiás, Brazil. 12 streams from the municipalities of Barro Alto and Niquelândia were sampled with trawl nets. During this study, 1247 fishes belonging to 27 species, 11 families, and three orders were collected. Characiformes comprised 1164 specimens of the sampled fishes, the most abundant order, while Perciformes was the less abundant order, with 17 collected specimens. Perciformes fishes were registered only in streams from Niquelândia. Astyanax elachylepis, Bryconops alburnoides and Astyanax aff. -

Tocantins, Brazil

Tocantins, Brazil Jurisdictional indicators brief State area: 277,721 km² (3.26% of Brazil) Original forest area: 39,853 km² Current forest area (2019): 9,964 km² (3.6% of Tocantins) Yearly deforestation (2019) 23 km² Yearly deforestation rate (2019) 0.23% Interannual deforestation change -8% (2018-2019) Accumulated deforestation (2001-2019): 1,800 km² Protected conservation areas: 38,548 km² (13.9% of Tocantins) Carbon stocks (2015): 62 millions tons (above ground biomass) Representative crops (2018): Sugarcane (3,106,492 tons); Soybean (2,667,936 tons); Rice (659,809 tons) Value of agricultural production (2016): $1,152,935,462 USD More on jurisdictional sustainability State of jurisdictional sustainability Index: Forest and people | Deforestation | Burned area | Emissions from deforestation | Livestock | Agriculture | Aquaculture Forest and people In 2019, the estimated area of tropical forest in the state of Tocantins was 9,964 km2, equivalent to 3.6% of the state’s total area, and to 0.3% of the tropical forest remaining in the nine states of the Brazilian legal Amazon. The total accumulated forest lost during the period 2001-2019 was 1,800 km2, equivalent to 16.1% of the forest area remaining in 2001. Tocantins concentrated about 0.2% of the carbon reserves stored in the biomass of the Brazilian tropical forest (about 62 mt C as of 2019). a b 100% 3.6% of the state is covered with forest DRAFT80% 60% 0.3% of Brazilian tropical forest area 40% 20% 0.2% of Brazilian tropical forest carbon stock 3.6% 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 2001 2019 No forest (%) Deforestation (%) Forest (%) Figure 1: a) forest share and b) transition of forest to deforestation over the last years There were 1.6 million people living in Tocantins as of 2020, distributed in 19 municipalities, with 0.3 million people living in the capital city of Palmas. -

Green Economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and Perspectives

Green economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and perspectives Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass Country Report Green economy Keywords: June 2014 green growth; green economy policy; environmental economics; participation; payments for environmental services About the author Virgilio Viana is Chief Executive of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável (Sustainable Amazonas Foundation) and International Fellow of IIED Cecilia Viana is a consultant and a doctoral student at the Center for Sustainable Development, University of Brasília Ana Euler is President-Director of the Amapá State Forestry Institute and Researcher at Embrapa-AP Maryanne Grieg-Gran is Principal Researcher (Economics) at IIED Steve Bass is Head of IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many participants at the two seminars on green economy in Amapá held in Macapá in March 2012 and March 2013, for their ideas and enthusiasm; the staff of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável for organising the trip of Amapá government staff to Amazonas; and Laura Jenks of IIED for editorial and project management assistance. The work was made possible by financial support to IIED from UK Aid; however the opinions in this paper are not necessarily those of the UK Government. Produced by IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group The Sustainable Markets Group drives IIED’s efforts to ensure that markets contribute to positive social, environmental and economic outcomes. The group brings together IIED’s work on market governance, business models, market failure, consumption, investment and the economics of climate change. Published by IIED, June 2014 Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass. -

Climate Change and Disasters: Analysis of the Brazilian Regional Inequality

Climate change and disasters: analysis of the Brazilian regional inequality Climate change and disasters: analysis of the Brazilian regional inequality Mudanças climáticas e desastres: análise da desigualdade regional brasileira Letícia Palazzi Pereza Saulo Rodrigues-Filhob José Antônio Marengoc Diogo V. Santosd Lucas Mikosze a Visiting professor at the Federal University of Paraíba Department of Architecture and Urbanism, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil E-mail: [email protected] b Professor at the University of Brasília, Sustainable Development Center Brasília, DF, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] c Head of Research and General R&D Coordinator at the Center for Monitoring and Early Warnings of Natural Disasters, Cemaden, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] d Vulnerability and Adaptation Supervisor in the scope of the Fourth Communication of Brazil to the Convention of Climate Change Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovations, MCTI, Brasília, DF, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] e Infrastructure analyst at Cenad, Ministry of Regional Development, Brasília, DF, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] doi:10.18472/SustDeb.v11n3.2020.33813 Received: 30/08/2020 Accepted: 10/11/2020 ARTICLE – DOSSIER Data and results presented in this article were developed under the project of the “Fourth National Communication and Biennial Update Reports of Brazil to the Climate Convention”, coordinated by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovations, with the support of the United Nations Development Programme and resources of the Global Environment Facility, to which we offer our thanks. Sustainability in Debate - Brasília, v. 11, n.3, p. 260-277, dez/2020 260 ISSN-e 2179-9067 Letícia Palazzi Perez et al. -

Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CONTENTS 46 DONATIONS 72 LEGAL 85 SPECIAL UNIT OBLIGATIONS PROJECTS UNIT UNIT 3 Letter from the CEO 47 COPAÍBAS 62 GEF TERRESTRE 73 FRANCISCANA 86 SUZANO 4 Perspectives Community, Protected Areas Strategies for the CONSERVATION Emergency Call Support 5 FUNBIO 25 years and Indigenous Peoples Project Conservation, Restoration and Conservation in Franciscana 87 PROJETO K 6 Mission, Vision and Values in the Brazilian Amazon and Management of Biodiversity Management Area I Knowledge for Action 7 SDG and Contributions Cerrado Savannah in the Caatinga, Pampa and 76 ENVIRONMENTAL 10 Timeline 50 ARPA Pantanal EDUCATION 16 FUNBIO Amazon Region Protected 64 ATLANTIC FOREST Implementing Environmental GEF AGENCY 16 How We Work Areas Program Biodiversity and Climate Education and Income- 88 17 In Numbers 53 REM MT Change in the Atlantic Forest generation Projects for FUNBIO 20 List of Funding Sources 2020 REDD Early Movers (REM) 65 PROBIO II Improved Environmental 21 Organizational Flow Chart Global Program – Mato Grosso Opportunities Fund of the Quality at Fishing 89 PRO-SPECIES 22 Governance 56 TRADITION AND FUTURE National Public/Private Communities in the State National Strategic Project 23 Transparency IN THE AMAZON Integrated Actions for of Rio de Janeiro for the Conservation of 24 Ethics Committee 57 KAYAPÓ FUND Biodiversity Project 78 MARINE AND FISHERIES Endangered Species 25 Policies and Safeguards 59 A MILLION TREES FOR 67 AMAPÁ FUND RESEARCH 26 National Agencies FUNBIO THE XINGU 68 ABROLHOS LAND Support for Marine and -

Divisão Territorial De Cuiabá

WILSON PEREIRA DOS SANTOS Prefeito Municipal de Cuiabá JACY RIBEIRO DE PROENÇA Vice Prefeita Municipal ANDELSON GIL DO AMARAL PEDRO PINTO DE OLIVEIRA ÉDEN CAPISTRANO PINTO JOÃO DE SOUZA VIEIRA FILHO Secretário Municipal de Governo Secretário Municipal de Secretário Municipal de Meio Secretário Municipal de Trabalho, Comunicação Ambiente e Desenvolvimento Urbano Desenv. Econômico e Turismo. JOSÉ ANTÔNIO ROSA GUILHERME FREDERICO MÜLLER OSCAR SOARES MARTINS ADRIANA BUSSIKI SANTOS Procurador Geral do Município Secretário Municipal de Secretário Municipal de Trânsito e Presidente do Instituto de Pesquisa Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. Transporte Urbano e Desenvolvimento Urbano MÁRIO OLÍMPIO MEDEIROS FILHO GUILHERME ANTÔNIO MALUF PEDRO LUIZ SHINOHARA JÚLIO CÉSAR PINHEIRO Secretário Municipal de Cultura Secretária Municipal de Saúde Secretário Municipal de Esporte e Presidente da Agência Municipal de Cidadania Habitação Popular CELCITA ROSA PINHEIRO DA SILVA JOSÉ CARLOS CARVALHO SOUZA EDUARDO ALEXANDRE RICCI RONALDO ROSA TAVEIRA Secretário Municipal de Assistência Secretário Municipal de Finanças Ouvidor Geral do Município de Presidente do Instituto de Prev. Social e Desenvolvimento Humano Cuiabá/Ombudsman Social dos Serv. de Cuiabá JOSÉ EUCLIDES DOS SANTOS FILHO CARLOS CARLÃO P. DO NASCIMENTO LUIZ MÁRIO DE BARROS JOSÉ ANTÔNIO ROSA Secretário Municipal de Infra- Secretário Municipal de Educação Auditoria e Controle Interno Diretor Presidente da Agência Estrutura Municipal de Saneamento PREFEITURA MUNICIPAL DE CUIABÁ INSTITUTO DE PLANEJAMENTO E DESENVOLVIMENTO URBANO DIRETORIA DE PESQUISA E INFORMAÇÃO ORGANIZAÇÃO GEOPOLÍTICA DE CUIABÁ • LIMITES MUNICIPAIS • LIMITES DOS DISTRITOS • LIMITE DO PERÍMETRO URBANO • ADMINISTRAÇÕES REGIONAIS • ABAIRRAMENTO Cuiabá, agosto de 2007. 2007. Prefeitura Municipal de Cuiabá/IPDU Ficha catalográfica CUIABÁ. Prefeitura Municipal de Cuiabá / Organização Geopolítica de Cuiabá. -

Pay for Performance and Deforestation: Evidence from Brazil ∗

Pay For Performance and Deforestation: Evidence from Brazil ∗ Liana O. Andersony Torfinn Hardingz Karlygash Kuralbayeva§ Ana M. Pessoa{ Po Yin Wongk May 2021 Abstract We study Brazil’s Bolsa Verde program, which pays extremely poor households for forest conservation. Using a triple difference approach, we find that the program keeps deforestation low in treated areas. In terms of reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, the program benefits are valued at approximately USD 335 million between 2011 and 2015, about 3 times the program costs. The treatment effects increase in the number of beneficiaries and are driven by action on non-private prop- erties. We show suggestive evidence that the BV program provides poor households with incentives to monitor and report on deforesta- tion. (JEL I38, O13, Q23, Q28, Q56) ∗The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway (project number 230860). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. We thank Andre de Lima for his expert assistance with maps and spatial data. We also thank participants at various conferences and seminars for very helpful comments and discussions. We are particularly thankful to Kelsey Jack, our discussant at the NBER SI Environment and Energy Economics 2019, for very detailed comments and suggestions. Remaining potential errors are our own. yNational Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN) zDepartment of Economics and Finance, University of Stavanger Business School §Department of Political Economy, King’s College London {National Institute for Space Research (INPE) kResearch Department, The Hong Kong Monetary Authority 1 1 Introduction The threat of climate change and the emergence of global climate polices have increased the world community’s attention to conservation.1 A crit- ical (and classical) question is how to best achieve conservation in devel- oping countries with weak enforcement mechanisms and limited financial resources. -

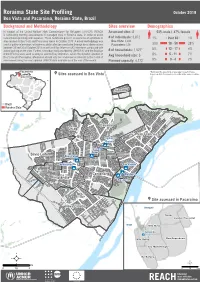

Roraima State Site Profiling. Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State

Roraima State Site Profiling October 2018 Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State, Brazil Background and Methodology Sites overview Demographics In support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), REACH Assessed sites: 8 53% male / 47% female 1+28+4+7+7 is conducting monthly assessments in managed sites in Roraima state, in order to assist 1+30+5+8+9 humanitarian planning and response. These factsheets present an overview of conditions in # of individuals: 3,872 1% 0ver 60 1% sites located in Boa Vista and Pacaraima towns in October 2018. A mixed methodology was Boa Vista: 3,444 used to gather information, with primary data collection conducted through direct observations Pacaraima: 428 30% 18 - 59 28% between 29 and 30 of October 2018 as well as 8 Key Informant (KI) interviews conducted with 5% 12 - 17 4% actors working on the sites. Further, secondary data provided by UNHCR KI and the Brazilian # of households: 1,527* Armed Forces were used to analyse selected key indicators. Given the dynamic situation in Avg household size: 3 8% 5 - 11 7% Boa Vista and Pacaraima, information should only be considered as relevant to the month of assessment using the most updated UNHCR data available as of the end of the month. Planned capacity: 4,172 9% 0 - 4 7% !(Pacaraima *Estimated by assuming an average household size, !( ¥Sites assessed in Boa Vista based on data from previous rounds in the same location. Boa Vista Cauamé Brazil Roraima State Cauamé União São Francisco Jardim Floresta ÔÆ Tancredo Neves Silvio Leite Nova Canaã ÔÆ ÔÆ Pintolândia São Vicente ÔÆ ÔÆ ÔÆ Centenário ÔÆ Rondon 1 Pintolândia Rondon 3 ¥Site assessed in Pacaraima Nova Cidade Venezuela Suapi Jardim Florestal Brazil Vila Nova Janokoida ÔÆ Das Orquídeas Vila Velha Ilzo Montenegro Da Balança ² ² km m 0 1,5 3 0 500 1.000 Fundo de População das Nações Unidas União Europeia Roraima site profiling October 2018 Jardim Floresta Boa Vista, Roraima State, Brazil Lat. -

Global Forest Resources Assessment (FRA) 2020 Brazil

Report Brazil Rome, 2020 FRA 2020 report, Brazil FAO has been monitoring the world's forests at 5 to 10 year intervals since 1946. The Global Forest Resources Assessments (FRA) are now produced every five years in an attempt to provide a consistent approach to describing the world's forests and how they are changing. The FRA is a country-driven process and the assessments are based on reports prepared by officially nominated National Correspondents. If a report is not available, the FRA Secretariat prepares a desk study using earlier reports, existing information and/or remote sensing based analysis. This document was generated automatically using the report made available as a contribution to the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, and submitted to FAO as an official government document. The content and the views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the entity submitting the report to FAO. FAO cannot be held responsible for any use made of the information contained in this document. 2 FRA 2020 report, Brazil TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Forest extent, characteristics and changes 2. Forest growing stock, biomass and carbon 3. Forest designation and management 4. Forest ownership and management rights 5. Forest disturbances 6. Forest policy and legislation 7. Employment, education and NWFP 8. Sustainable Development Goal 15 3 FRA 2020 report, Brazil Introduction Report preparation and contact persons The present report was prepared by the following person(s) Name Role Email Tables Ana Laura Cerqueira Trindade Collaborator ana.trindade@florestal.gov.br All Humberto Navarro de Mesquita Junior Collaborator humberto.mesquita-junior@florestal.gov.br All Joberto Veloso de Freitas National correspondent joberto.freitas@florestal.gov.br All Introductory text Brazil holds the world’s second largest forest area and the importance of its natural forests has recognized importance at the national and global levels, both due to its extension and its associated values, such as biodiversity conservation. -

Amazon Alive!

Amazon Alive! A decade of discovery 1999-2009 The Amazon is the planet’s largest rainforest and river basin. It supports countless thousands of species, as well as 30 million people. © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK © Brent Stirton / Getty Images The Amazon is the largest rainforest on Earth. It’s famed for its unrivalled biological diversity, with wildlife that includes jaguars, river dolphins, manatees, giant otters, capybaras, harpy eagles, anacondas and piranhas. The many unique habitats in this globally significant region conceal a wealth of hidden species, which scientists continue to discover at an incredible rate. Between 1999 and 2009, at least 1,200 new species of plants and vertebrates have been discovered in the Amazon biome (see page 6 for a map showing the extent of the region that this spans). The new species include 637 plants, 257 fish, 216 amphibians, 55 reptiles, 16 birds and 39 mammals. In addition, thousands of new invertebrate species have been uncovered. Owing to the sheer number of the latter, these are not covered in detail by this report. This report has tried to be comprehensive in its listing of new plants and vertebrates described from the Amazon biome in the last decade. But for the largest groups of life on Earth, such as invertebrates, such lists do not exist – so the number of new species presented here is no doubt an underestimate. Cover image: Ranitomeya benedicta, new poison frog species © Evan Twomey amazon alive! i a decade of discovery 1999-2009 1 Ahmed Djoghlaf, Executive Secretary, Foreword Convention on Biological Diversity The vital importance of the Amazon rainforest is very basic work on the natural history of the well known. -

The Influence of Historical and Potential Future Deforestation on The

Journal of Hydrology 369 (2009) 165–174 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hydrology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol The influence of historical and potential future deforestation on the stream flow of the Amazon River – Land surface processes and atmospheric feedbacks Michael T. Coe a,*, Marcos H. Costa b, Britaldo S. Soares-Filho c a The Woods Hole Research Center, 149 Woods Hole Rd., Falmouth, MA 02540, USA b The Federal University of Viçosa, Viçosa, MG, 36570-000, Brazil c The Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil article info summary Article history: In this study, results from two sets of numerical simulations are evaluated and presented; one with the Received 18 June 2008 land surface model IBIS forced with prescribed climate and another with the fully coupled atmospheric Received in revised form 27 October 2008 general circulation and land surface model CCM3-IBIS. The results illustrate the influence of historical and Accepted 15 February 2009 potential future deforestation on local evapotranspiration and discharge of the Amazon River system with and without atmospheric feedbacks and clarify a few important points about the impact of defor- This manuscript was handled by K. estation on the Amazon River. In the absence of a continental scale precipitation change, large-scale Georgakakos, Editor-in-Chief, with the deforestation can have a significant impact on large river systems and appears to have already done so assistance of Phillip Arkin, Associate Editor in the Tocantins and Araguaia Rivers, where discharge has increased 25% with little change in precipita- tion. However, with extensive deforestation (e.g. -

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001†

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001† by Maria Goreti Rosa-Freitas*, Pantelis Tsouris**#, Alexander Sibajev***, Ellem Tatiani de Souza Weimann**, Alexandre Ubirajara Marques**, Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira** and José Francisco Luitgards-Moura*** *Laboratório de Transmissores de Hematozoários, Departamento de Entomologia, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Av. Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil **Núcleo Avançado de Vetores – Convênio FIOCRUZ-UFRR BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil ***Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, UFRR, BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil Abstract In Brazil, as in the rest of the world, dengue has become the most important arthropod-borne viral disease of public health significance. Roraima state presented the highest dengue incidence coefficient in Brazil in the last few years (224.9 and 164.2 per 10,000 inhabitants in 2000 and 2001, respectively). The capital, Boa Vista, reports the highest number of dengue cases in Roraima. This study examined the temporal and spatial distribution of dengue in Boa Vista during the years 1999- 2001, based on daily notifications as recorded by local health authorities. Temporally, dengue notifications were analysed by weekly and monthly averages and age distribution and correlated to meteorological variables. Spatially, dengue coefficients, premises infestation indices, population density and income levels were allocated in a geographical information system using, Boa Vista 49 neighbourhoods as units. Dengue outbreaks displayed distinct year-to-year distribution patterns that were neither periodical nor significantly correlated to any meteorological variable. There were no preferences for age and sex.