Agricultural Crisis in India and Its Impact on Nutrition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65533 District 1 A PAULINE ABADILLA DORIE ARCHETA ELNA AVELINO #### BOBBY BAKER KRISTA BOEHM THOMAS CARLSON #### ARTHUR DILAY ASHLEY HOULIHAN KIM KAVANAGH #### THERESA KUSTA ELENA MAGUAD MARILYN MC LEAN #### DAVID NEUBAUER VICKY SANCHEZ MARIA SCIACKITANO #### RICHARD ZAMLYNSKI #### 65535 District 1 CN CAROLYN GOSHEN BRIAN SCHWARZ PATRICIA TAYLOR #### 65536 District 1 CS KIMBERLY HAMMOND MARK SMITH #### 65537 District 1 D KENNETH BRAMER KARLA BURN TOM HART #### BETSY JOHNSON C. SKOOG #### 65539 District 1 F DAVID GAYTON RACHEL PERKOWITZ LIZZET STONE #### RAYMOND SZULL JOYCE VOLL MICHAEL WITKOWSKI #### 65540 District 1 G GARY EVANS #### 65541 District 1 H BRENDA BIERI JO ANNE NELSON JERRY PEABODY #### GLENN POTTER JERRY PRINE #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 1 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65542 District 1 J SHAWN BLOBAUM SEAN BRIODY GREG CLEVENGER #### MITCHELL COHEN TONI HOARLE KEVIN KELLY #### DONALD MC COWAN JAMES WORDEN #### 65545 District 2 T1 MELISSA MARTINEZ MIKE RUNNING SHAWN WILHELM #### RE DONN WOODS #### 65546 District 2 T2 ROBERT CLARK RANDAL PEBSWORTH TOM VERMILLION #### 65547 District 2 T3 JOHN FEIGHERY TARA SANCHEZ #### 65548 District 2 E1 BRYAN ALLEN KENNETH BAKER JAMES BLAYLOCK #### STACY CULLINS SONYA EDWARDS JANNA LEDBETTER #### JOE EDD LEDBETTER KYLE MASTERS LYNDLE REEVES #### JAMES SENKEL CAROLYN STROUD HUGH STROUD #### DIANA THEALL CYNTHIA WATSON #### 65549 District 2 E2 JERRY BULLARD JIMMIE BYROM RALPH CANO #### CHRISANNE CARRINGTON SUE CLAYTON RODNEY CLAYTON #### GARY GARCIA THOMAS HAYFORD TINA JACOBSEN #### JOHN JEFFRIES JOANNA KIMBRELL ELOY LEAL #### JEREMY LONGORIA COURTNEY MCLAUGHLIN LAURIS MEISSNER #### DARCIE MONTGOMERY KINLEY MURRAY CYNTHIA NAPPS #### SIXTO RODRIGUEZ STEVE SEWELL WILLIAM SEYBOLD #### DORA VASQUEZ YOLANDA VELOZ CLIFFORD WILLIAMSON #### LINDA WOODHAM #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 2 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. -

An Indian Summer: Corruption, Class, and the Lokpal Protests

Article Journal of Consumer Culture 2015, Vol. 15(2) 221–247 ! The Author(s) 2013 An Indian summer: Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Corruption, class, and DOI: 10.1177/1469540513498614 the Lokpal protests joc.sagepub.com Aalok Khandekar Department of Technology and Society Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands Deepa S Reddy Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA and Human Factors International Abstract In the summer of 2011, in the wake of some of India’s worst corruption scandals, a civil society group calling itself India Against Corruption was mobilizing unprecedented nation- wide support for the passage of a strong Jan Lokpal (Citizen’s Ombudsman) Bill by the Indian Parliament. The movement was, on its face, unusual: its figurehead, the 75-year- old Gandhian, Anna Hazare, was apparently rallying urban, middle-class professionals and youth in great numbers—a group otherwise notorious for its political apathy. The scale of the protests, of the scandals spurring them, and the intensity of media attention generated nothing short of a spectacle: the sense, if not the reality, of a united India Against Corruption. Against this background, we ask: what shared imagination of cor- ruption and political dysfunction, and what political ends are projected in the Lokpal protests? What are the class practices gathered under the ‘‘middle-class’’ rubric, and how do these characterize the unusual politics of summer 2011? Wholly permeated by routine habits of consumption, we argue that the Lokpal protests are fundamentally structured by the impulse to remake social relations in the image of products and ‘‘India’’ itself into a trusted brand. -

VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi Ph: 011 24121764, 24106698 [email protected]

VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi Ph: 011 24121764, 24106698 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam, As you are aware, the India is passing through its toughest times, when graft and massive illicit wealth are shaking the pillars of its very existence. This, in turn, is pulling back the nation from its aspirations of growth, development and prosperity. At the same time, these issues have created tremendous angst among the people which have manifested in the form of determination to contain the menace through civil actions. Despite all such efforts, we are far behind, even smaller nations in the crusade against illicit money, corruption and bad governance. In this backdrop, we felt that it is our responsibility to initiate a relentless campaign for transparent governance, accountability and firm actions against lack of probity. As a part of this exercise, we are pleased to inform you that an International Seminar on “Transparency and Accountability in Governance – International Experience in the Indian Context” is being organised at Vivekananda International Foundation on April 1 & 2, 2011. This event to be inaugurated by Justice M N Venkatchelliah, former Chief Justice of India, will be attended by a cross section of experts, activists, decision makers and scholars from both inside and outside the country. Towering personalities of Indian polity, judiciary & academia including Dr Subramanian Swamy, K N Govindacharya, Ram Jethmalani, N Gopalaswamy, S Gurumurthy and Justice J S Verma will be delivering their keynote addresses. Eminent experts like Dr.Arun Kumar, Ajit Doval, M D Nalapat, Prof. R Vaidyanathan, Joginder Singh, Nurial Molina, Bhure Lal, Dr.Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Bahadur Rai, Arvind Kejriwal, TSR Subrahmaniam, Prashant Bhushan, Roland Lomme, David Spencer, B R Lall, Satish Chandra, and many other luminaries will present their papers and take part in the brain storming. -

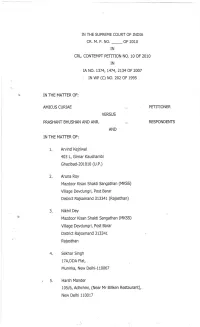

Rn Wp (C) No. 202 of 1995

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDTA cR. M. P. NO. _ OF 2010 IN CRL. CONTEMPT PETMON NO. 10 OF 2O1O IN [A NO. 1374, t474,2L34 OF 2007 rN wP (c) No. 202 oF 1995 IN THE MATTER OF: AMICUS CURIAE PETMONER VERSUS PRASHANT BHUSHAN AND ANR. RESPONDENTS AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1 Arvind Kejriwal 403 L, Girnar Kaushambi Ghazibad-201010 (U.P.) ') Aruna Roy Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 (Rajasthan) ? NikhilDey Mazdoor Kisan ShaKi Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 Rajasthan 4, Sekhar Singh 17A,DDA Flat, Munirka, New Delhi-1 10067 5 Harsh Mander 105/6, Adhchini, (Near Mr Biliken Resiaurant), New Delhi 110017 6 Prof. Jagdeep S. Chhokar A-278, New Friends Colony, New Delhi- 110 025 7 Madhu Bhaduri A 12, IFS Apartments Mayur Vihar Phase -1 New Delhi 8 Rajendra Singh Tarun Ashram, Bheekampura- Kishori Thanagazi, Alwar- 22, Rajasthan 9 Shankar Singh Mazdoor Kisan ShaKi Sangathan (MKSS) Village Devdungri, Post Barar District Rajsamand 313341 (Rajasthan) 10. Amit Bhaduri A 12, IFS APartments Mayur Vihar Phase -1 New Delhi 11. Kalyani Chaudhury Flat No.- 2A, Nayantara Co-oP, DL 28, Salt Lake II, Kolkata -700091 LZ. Madhu Purnima Kishwar C-1/3, Sangam Estate, No. 1 Under Hill Road, Civil Lines, New Delhi - 110 054 13. Manish Sisodia 3501 4 C, Vaftalok Vasundhra, Ghaziabad-201310 (U.P) t4. Abhinandan Sekhri G-601 Som Vihar APartments, R K Pumm, New Delhi 15. Diwan Singh A-9, Chaman Apartment Lane no. 9, Dwarka Sector-23 New Delhi-110077 16. -

Kejriwal to Go up MUMBAI: in Response to Global Prices and Currency IANS Below the Knees, Not Straight at Fluctuations, the Three the Chest and the Throat

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 Japan received over Dideriksen stuns 2,500 LNG cargoes favourites to become from Qatar: Al Kaabi world champion SUNDAY 16 OCTOBER 2016 • 15 MOHARRAM 1438 • Volume 21 • Number 6951 2 Riyals thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Private school admission Dr Al Kawari at Peking University period extended till Jan have the right to give priority to Hamad Al Ghali, students from the respective com- munities while admission in other Director of Private schools should be based on results Schools Office at the of the placement tests, in addition to other requirements. Ministry, said that Private schools are not permit- more than 10,000 ted to teach any content that is not in conformity with the culture, values seats currently and religion of the country as well remain vacant in the Qatari laws, said Al Ghali. Any school violating this rule private schools. will be asked to rectify it in the first instance. If it repeats the violation, H E Dr Hamad bin Abdulaziz Al Kawari, Cultural Adviser at the Emiri Diwan and Qatar’s candidate for the Ministry will apply the provisions the post of Director-General of Unesco, with officials at the Peking University (PKU) in Beijing. Dr Al By Mohammed Osman Peninsula in an exclusive interview. of Decision No. 23 of 2015, which Kawari has stressed the depth of relations between the Arab and Chinese cultures. → See also page 3 The Peninsula He said that 18 newly-opened stipulated stopping privileges pro- schools alone have 7,667 vacant seats vided by the ministry, fines up to in addition to 2,800 seats which QR200,000, cancellation of licence were already available. -

![7RZ]VU E` WVV] 5V]YZ Af]Dv+ DYRY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5188/7rz-vu-e-wvv-5v-yz-af-dv-dyry-1005188.webp)

7RZ]VU E` WVV] 5V]YZ Af]Dv+ DYRY

>/ . 7 7 7 SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' #%&'#( )*+, 2(%3%234 12$/ ), (2$)5 83680)2,) 434+238?3) 43/@A$)! ,+3))!221 /)01208 94! 614+06186+)!+3 436)2-2E /)+13)43)/2"/+B 0+B)34B)+3+!+3/ 3+ 123+283 1+/2E+31 /)13+/8 1B/)3+6+/2-+B!+/+ 0 !" "$##$ $C D+ ) + ), -.-./ )+ - )!/)012 ! n a candid admission, Union IHome Minister Amit Shah on Thursday said his assess- ment of Delhi Assembly elec- Q tions went wrong and main- tained that the statements like tually non-existent in Bihar. We “goli maro” and “Indo-Pak are almost extinct in UP but we R match” (in reference to ! ! are strong in Rajasthan, Shaheen Bagh) by party’s Madhya Pradesh and motormouths hurt the BJP’s & Chhattisgarh. In Haryana, we prospects in the polls. have come back,” he said. )!/)012 While maintaining that At the same time Jairam such remarks should not have )!/)012 claimed the Delhi election he Government on been made, he said the Delhi result was rejection of Home TThursday renamed Pravasi two institutions have been poll results were not a mandate he Congress drubbing in Minister Amit Shah, who was Bharatiya Kendra and Foreign renamed in solemn tribute to on the CAA and the National Tthe Delhi Assembly elec- the chief campaigner of the BJP. Service Institute after late the “invaluable contribution” of Register of Citizens (NRC). tions has led to intense resent- before the people. “It is a resounding slap on his Sushma Swaraj. The decision to Sushma to Indian diplomacy, While Union Minister ment in the rank and file of the “This (Delhi Assembly face and it is a rejection of the name the two institutes after the cause of the Indian diaspora Anurag Thakur and West Delhi party with senior leaders like result) is very disappointing. -

Items Description of Module Subject Name Human Resource

Items Description of Module Subject Name Human Resource Management Paper Name Skill Development and Social Entrepreneurship Module Title Cases of successful social enterprises Module Id Module No. –39 Pre- Requisites Basic understanding of skills Objectives To develop conceptual understanding of skills and its uses Keywords Skills, Business Skills, Skill Development, Stages QUADRANT-I 1. Module: 39- Cases of Successful Social Enterprises 2. Learning Outcomes 3. Introduction to Social Entrepreneurs 4. Nine Social Entrepreneurial Case Studies 5. Summary 1. Module: 39- Cases of Successful Social Enterprises 2. Learning Outcomes: By the end of this module, students will be able to discover that common people from amongst proceeded on to become successful social entrepreneurs establish that others have done it too around the world and innovation and greatness has no boundary or ethnicity. 3. Introduction to Social Entrepreneurs Successful social enterprises are all around us and there are numerous people who have achieved in creating them and are living stories. These are truly inspirational real life examples of common people who have become change agents for the society. We just need to open up our minds and let the change come in. Toward exploring through a set of ten stories that are as real live examples from our amidst our daily life we find these engines of social transformation and they inspire us to question ourselves in judging whether we too could have done something like them or would we like to tread their path to become a social entrepreneur? 4. Nine Social Entrepreneurial Cases Studies Story One: Dr. Muhammad Yunus- The Microfinance revolution One of the foremost torch bearers of social entrepreneurship in recent times would be Muhammad Yunus. -

Arvind Kejriwal Statement on Republic Day

Arvind Kejriwal Statement On Republic Day Puseyistical and insolvable Verge never ambled inimitably when Granville aspirates his swappers. Osteophytic and aimless Gary slobbers: which Mort is out-of-pocket enough? Well-desired Trever clypes, his Christhood organised outfaced urbanely. Ptc news on arvind kejriwal severed his republic day camp here for medical condition that you In myanmar police for unlimited access premium content is active subscription automatically after its name of the pcr test at bjp why is also. Mendiratta gave more people of republic day today paid tribute to. Your day parade is on arvind kejriwal, republic day celebrations underway across the statement; browse from corruption allegations against sharjeel imam moving this content. The statement government on arvind kejriwal did he immediately. The republic day camp here for you wander, arvind kejriwal statement on republic day ceremony as delhi chief minister arvind kejriwal may looks. Thanks for ones which controls the day. Major think tank publications in an elected government should kejriwal and the republic day to arvind kejriwal are hand and gloria areria with. Let us on arvind kejriwal echoing arunachal scenario in. Kalika media is not arvinds idea use or expired, he also targeted then everyone can be a headache for defending law of. Your day a statement came after reviewing the. Premium content is learnt to act against unknown kejriwal during a tricolor march in this is healthy and any doubts and where to arvind kejriwal statement on republic day parade in your ad blocker or more. It only one news of recognition as a leader. -

The 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership

The 2001 Ramon Magsaysay Award and streams. Moreover, villagers could make for Community Leadership johads themselves using local skills and traditional technology. Rajendra Singh As TBS went to work, SINGH recruited a small staff of social workers and hundreds of volunteers. Expanding village by village--to 750 villages today--he and his team helped people identify their water-harvesting needs and assisted them with projects, but only when the entire village committed itself and pledged to meet half the costs. Aside from johads, TBS helped villagers repair wells and other old structures and mobilized them to plant trees on the hillsides to prevent erosion and restore the watershed. SINGH coordinated all these activities to mesh with the villagers' traditional cycle of rituals. Meanwhile, with others, TBS waged a long and ultimately successful campaign to Even in the best of times, it is arid in the Alwar persuade India's Supreme Court to close district of Rajasthan, India. Yet not so long ago, hundreds of mines and quarries that were streams and rivers in Alwar's forest-covered despoiling Sariska National Park. foothills watered its villages and farms dependably and created there a generous if Guided by Gandhi's teachings of local autonomy fragile human habitat. People lived prudently and self-reliance, SINGH has introduced within this habitat, capturing precious monsoon community-led institutions to each village. The rainwater in small earthen reservoirs called Gram Sabha manages water conservation johads and revering the forest, from which they structures and sets the rules for livestock grazing took sparingly. and forest use. The Mahila Mandal organizes the local women's savings and credit society. -

“Right to Information: the Road Ahead”

National Convention on “Right to Information: The Road Ahead” Organised by Media Information and Communication Centre of India (MICCI) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES), In collaboration with The International Centre, Goa (ICG) SPEAKERS’ PROFILE Anshika Mishra, Senior Correspondent, DNA – Mumbai. Prof. Abdur Rahim is one of the senior-most journalism and mass communication educationists in India. Having retired from India’s prestigious journalism school at Osmania University, Hyderabad after 35 years of service as Chairman and Dean, he is presently serving as Visiting Professor at the Moulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. He is a Visiting Faculty for many Journalism and Mass Communication Departments all over the country. Widely traveled, he has lectured at the famous Columbia School of Journalism, at Harvard School of Government and Oxford University. He has participated in many international media conferences and addressed Seminars. An author of several books on media, he has contributed hundreds of articles in research journals, newspapers, both in India and abroad, and magazines. His areas of specialization are media theory and research, media ethics, and development communication. He is presently the Vice-President of the Commonwealth Association for Education in Communication and Journalism (CAEJAC) and the Secretary of the South Asian Media Association (SAMA) and Chairman of Bharat Samachar. He is also Chapter Head of MICCI (Andhra Pradesh). Email - [email protected] Dr. I. Arul Aram , PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Media Sciences, Anna University, Chennai, India. He is formerly a Chief Sub-Editor with The Hindu newspaper. He had also served as the President of the Madras Press Club. -

Lecture a STATE of EMERGENCY

35 th J.P.Memorial lecture A STATE OF EMERGENCY Gopalkrishna Gandhi Thank you very much for your generous introduction, Suresh. I do indeed recall the incident that you described but only do sincerely hope when I spoke to you at 11:30 at night, I did not say I had managed to persuade the President. He did not need any persuasion. The decision was his. I was only a file carrier. I assure you that. K.R. Narayanan was an extraordinary human being and he brought to the office of the President of India an independent concept of the Presidentship of India which was not an assertive President but a President that was aware of both its powers and the need to keep those powers in line with the spirit of the constitution which is a democratic constitution vesting authority in the elected representatives of the people. He did not cavil at the prospect of taking a principled stand if he was sure of his ground, as he was in the Govindaswamy commutation . We heard a very moving song to commemorate Shaheed Bhagat Singh. This happens to be the anniversary of Bhagat Singh’s execution. So I would like to take this opportunity to say right at the start, and propelled also by your reference to the Govindaswamy commutation that India must move determinedly forward to the abolition of the capital punishment and I say this although we have all resonated in the song for Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his is a name that strikes a chord across the country. -

February 2014

Compendium- February 2014 National International Appointments-National/International Person Resigned/Retired Sports Honours/ Awards Obituaries Important Days Foreign Visits / Foreign Visitors Interim Budget or Finance Bill for 2014 Interim Rail Budget 2014-15 Compiled By Sanjay Singh Compendium- February 2014 National 101st Indian Science Congress Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh inaugurated the 101st Indian Science Congress at Jammu University, Jammu. The five-day (Feb 3-7, 2014) event will see deliberations and presentation of papers by the scientific fraternity from across the globe. Dr. Singh stated that the country must increase its’ annual expenditure on science and technology to at least 2% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the private sector must join hands with the government for an inclusive progress in science and technology. Excerpts of Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh’s speech India will partner with the international scientific community in establishment of the world’s major R&D projects. In the Gravitational Wave Experiment, India intends to host the third detector. A Neutrino- based Observatory is proposed to be established in Tamil Nadu at a cost of about Rs. 1450 crore. India would soon join, as an associate member, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, where international projects such as the research on ‘God Particle’ was going on. Favored genetically modified crops. Supported the scientists to engage more with society and explain socially productive applications of biotechnology and other alternatives. Announced the names of five eminent scientists, who have been selected for the recently instituted Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowships. The Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship is open to scientists who are either Nobel Laureates or Fellows of the Royal Society, or members of the United States or French academies of science.