Hoover Digest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia's Kaine Has Big Early Lead In

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: FEBRUARY 17, 2017 VIRGINIA’S KAINE HAS BIG EARLY LEAD IN SENATE RACE, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; TRUMP DEEP IN A JOB APPROVAL HOLE Two well-known Republican women who might challenge Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine for reelection in 2018 get no help from their sisters, as Kaine leads among women by 23 percentage points in either race, leaving him with a comfortable overall lead, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. Sen. Kaine leads Republican talk show host Laura Ingraham 56 – 36 percent among all voters and tops businesswoman Carly Fiorina 57 – 36 percent, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds. In the Kaine-Ingraham matchup, the Democrat leads 57 – 34 percent among women and 54 – 39 percent among men. He takes Democrats 98 – 1 percent and independent voters 54 – 32 percent. Republicans back Ingraham 86 – 8 percent. White voters are divided with 48 percent for Kaine and 45 percent for Ingraham. Non- white voters go to Kaine 74 – 15 percent. Kaine leads Fiorina 57 – 34 percent among women and 56 – 39 percent among men, 98 – 1 percent among Democrats and 55 – 32 percent among independent voters. Republicans back Fiorina 86 – 8 percent. He gets 49 percent of white voters to 45 percent for Fiorina. Non- white voters back Kaine 75 – 16 percent. “There is a certain similarity to how Virginia voters see Republican officials and potential GOP candidates these days. As was evident in the Quinnipiac University poll earlier this week that showed the Democratic candidates for governor were running better than their Republican counterparts, the same pattern holds true for President Donald Trump's job approval and for an early look at Sen. -

Trade Summit Collapses HE Ataturk Thought As- His Group

32 WEDNESDAY, JULY 30, 2008 THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. ON OTHER FRONTS 7 Dispatch / By Andrew Higgins VOL. XXVI NO. 126 WEDNESDAY, JULY 30, 2008 Œ2.90 Œ2.90 China weighs new curbs as Turkey battles issue: What would Ataturk do? - Spain 7 - France pollution threatens Games Ankara, Turkey signs of this, he says, are the woes of NEWS IN DEPTH | PAGES 14-15 Sk 100 Œ3.20 Trade summit collapses HE Ataturk Thought As- his group. sociation,zealousguard- The governing party’s own claim - Slovakia ian of the secular creed of allegiance to Ataturk only demon- - Finland Merrill Lynch fire sale may Food-tariffs impasse that guides Turkey, stratesitsdeviousness,saysMr.Kara- Œ3 never thought it would man. When Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Dkr 22 burn fingers on Wall Street leaves Doha Round Tcome to this. now Turkey’s prime minister, - Portugal MONEY & INVESTING | PAGE 17 Its chairman, a retired four-star launched the AK Party in 2001, he did dead in the water - Denmark general, is in jail. Its offices—plas- so in a hall bedecked with a giant por- Zl 10.50 tered with portraits of modern Tur- traitofAtaturk.Theeventbeganwith By John W. Miller Kc 110 key’sfoundingfather,MustafaKemal a minute’s silence in Ataturk’s mem- - Poland Ataturk—have been raided by police. ory. “All fake,” huffs Mr. Karaman. GENEVA—A marathon trade Several of its computer hard drives Suat Kiniklioglu, an AK Party leg- Nkr 27 summit aimed at closing the so- have been seized by investigators. islator, says he has “no problems at What’s News— called Doha Round of global trade - Czech Republic They’re hunting for evidence of plots all” with “Ataturk’s principles” but - Norway negotiations collapsed Tuesday, af- 7 Business&Finance World-Wide 7 byhard-lineseculariststotoppleTur- the key issue is “how we interpret Œ2.90 ter a standoff over food tariffs ex- key’s mildly Islamic government. -

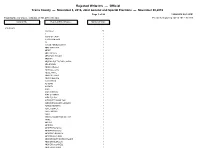

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Preface Chapter 1

Notes Preface 1. Alfred Pearce Dennis, “Humanizing the Department of Commerce,” Saturday Evening Post, June 6, 1925, 8. 2. Herbert Hoover, Memoirs: The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920–1930 (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 184. 3. Herbert Hoover, “The Larger Purposes of the Department of Commerce,” in “Republi- can National Committee, Brief Review of Activities and Policies of the Federal Executive Departments,” Bulletin No. 6, 1928, Herbert Hoover Papers, Campaign and Transition Period, Box 6, “Subject: Republican National Committee,” Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa. 4. Herbert Hoover, “Responsibility of America for World Peace,” address before national con- vention of National League of Women Voters, Des Moines, Iowa, April 11, 1923, Bible no. 303, Hoover Presidential Library. 5. Bruce Bliven, “Hoover—And the Rest,” Independent, May 29, 1920, 275. Chapter 1 1. John W. Hallowell to Arthur (Hallowell?), November 21, 1918, Hoover Papers, Pre-Com- merce Period, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 6, “Hallowell, John W., 1917–1920”; Julius Barnes to Gertrude Barnes, November 27 and December 5, 1918, ibid., Box 2, “Barnes, Julius H., Nov. 27, 1918–Jan. 17, 1919”; Lewis Strauss, “Further Notes for Mr. Irwin,” ca. February 1928, Subject File, Lewis L. Strauss Papers, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 10, “Campaign of 1928: Campaign Literature, Speeches, etc., Press Releases, Speeches, etc., 1928 Feb.–Nov.”; Strauss, handwritten notes, December 1, 1918, ibid., Box 76, “Strauss, Lewis L., Diaries, 1917–19.” 2. The men who sailed with Hoover to Europe on the Olympic on November 18, 1918, were Julius Barnes, Frederick Chatfi eld, John Hallowell, Lewis Strauss, Robert Taft, and Alonzo Taylor. -

H-Diplo ESSAY 233

H-Diplo ESSAY 233 Essay Series on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars 22 May 2020 Roads Less Traveled https://hdiplo.org/to/E233 Series Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Essay by Elizabeth Cobbs, Texas A&M University thought of myself as calm. Competing for a grant that paid for three years of graduate study at any university in the nation seemed straightforward, even though $100,000 was at stake and I had at most $500 in savings. The interview I should have been easy, plus I was hard to rattle. My nerves did not forewarn me that they were not in agreement. On the flight to San Francisco in 1983 I reviewed what the panel might ask. I needed to explain why I wished to earn a Ph.D. in history even though my major and minors had been in literature, philosophy, and political science, and I had taken only three electives in history. The professor who taught those three classes was the most interesting one I had ever had, and he convinced me to switch disciplines for graduate school. Everything had been in preparation for the study of U.S. foreign relations, a bright and promising endeavor where I could apply all my tools. My instinctive confidence sprang from difficult but useful experience. I grew up as the middle child in a San Diego construction family of nine (natural training for a diplomat!), but paternal abuse forced me to leave home at the age of fourteen. My first job, which I got by lying about my age, was at Taco Bell. -

RUSSO-FINNISH RELATIONS, 1937-1947 a Thesis Presented To

RUSSO-FINNISH RELATIONS, 1937-1947 A Thesis Presented to the Department of History Carroll College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Academic Honors with a B.A. Degree In History by Rex Allen Martin April 2, 1973 SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge thankfully A. Patanen, Attach^ to the Embassy of Finland, and Mrs. Anna-Malja Kurlkka of the Library of Parliament in Helsinki for their aid in locating the documents used In my research. For his aid In obtaining research material, I wish to thank Mr. H. Palmer of the Inter-Library Loan Department of Carroll College. To Mr. Lang and to Dr. Semmens, my thanks for their time and effort. To Father William Greytak, without whose encouragement, guidance, and suggestions this thesis would never have been completed, I express my warmest thanks. Rex A. Martin 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... v I. 1937 TO 1939 ........................................................................................ 1 II. 1939 TO1 940.................................................... 31 III. 1940 TO1 941............................................................................................. 49 IV. 1941 TO1 944 ......................................................................................... 70 V. 1944 TO 1947 ........................................................................................ -

Defence Acquisition

Defence acquisition Alex Wild and Elizabeth Oakes 17th May 2016 He efficient procurement of defence equipment has long been a challenge for British governments. It is an extremely complex process that is yet to be mastered with vast T sums of money invariably at stake – procurement and support of military equipment consumes around 40 per cent of annual defence cash expenditure1. In 2013-14 Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) spent £13.9bn buying and supporting military equipment2. With the House of Commons set to vote on the “Main Gate” decision to replace Trident in 2016, the government is set to embark on what will probably be the last major acquisition programme in the current round of the Royal Navy’s post-Cold War modernisation strategy. It’s crucial that the errors of the past are not repeated. Introduction There has been no shortage of reports from the likes of the National Audit Office and the Public Accounts Committee on the subject of defence acquisition. By 2010 a £38bn gap had opened up between the equipment programme and the defence budget. £1.5bn was being lost annually due to poor skills and management, the failure to make strategic investment decisions due to blurred roles and accountabilities and delays to projects3. In 2008, the then Secretary of State for Defence, John Hutton, commissioned Bernard Gray to produce a review of defence acquisition. The findings were published in October 2009. The following criticisms of the procurement process were made4: 1 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 2 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 3 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 4 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 1 [email protected] Too many types of equipment are ordered for too large a range of tasks at too high a specification. -

Appendix 1 – the Evolution of HMS Dorsetshire

Appendix 1 – The Evolution of HMS Dorsetshire This image and the one on the next page show Dorsetshire in 1930, during builder’s trials1 Dorsetshire in July 19312 Dorsetshire in 1932.At this time her secondary and tertiary armament is still very light, just four single 4-inch guns abreast the forward funnels and four single 2-pdr pompoms abreast the bridge3 This 1948 model, shown to better advantage on the next page, depicts Dorsetshire under refit in 1937 in No. 14 Dock at Portsmouth Dockyard. The twin 4-inch mountings are in place abreast the funnels, as are the octuple 2-pounder pom poms aft of the torpedo tubes.4 Dorsetshire in dock at Singapore after her 1937 refit.5 This image and the one on the next page show how difficult it was for her to engage aircraft attacking from directly ahead. The arrows highlight her guns as follows: blue = twin 4-inch red = quad .5-inch green = octuple 2-pdr pom poms Dorsetshire in 19416 Three shots of Dorsetshire in 1941. The painting of the aft funnel and part of the hull in a light colour was meant to make her appear to be a single-funnelled vessel – a sloop, according to one source. The paint scheme was possibly first applied at Simonstown between 16 and 20 March, since this was apparently Dorsetshire’s only docking between December 1940 and June-July 1941. The top image was taken at Cape Town, possibly between 21 and 23 April 1941. The centre image was presumably taken prior to the June-July refit, since the ship sports what seems to have been the original version of this paint scheme. -

Life As a First Lady Revealed Bob Wolz, Harry S

Life as a First Lady Revealed Bob Wolz, Harry S. Truman Little White House Executive Director On Saturday, February 25, 2012, saw presidential family members gather on the lawn of the Little White House to discuss their mothers and grandmothers as First Ladies of the United States. Margaret Hoover, a FOX News commentator, revealed a long forgotten Lou Hoover who sounded like an incredibly accomplished “modern woman”. Lou Hoover was the first American woman to earn a degree in geology from Stanford, where she met her future husband in a geology lab. She backpacked and was an expert marksman… hardly what we ‘d expect from a First Lady. She and Herbert Hoover trans-navigated the world five times by ship. Museum Director Bob Wolz shows Susan Ford, Clifton Truman Daniel and Margaret Hoover She was a gifted linguist and spoke fluent an original copy of the Dewey Defeats Truman article. Mandarin. She and Herbert were running Truman was, instead, intensely private. Her father had committed mining operations in China when the Boxer Rebellion broke out. suicide while she was a teen and she always feared that exposure of Gangs of Chinese threatened all westerners. Lou Hoover, armed with that would embarrass her husband or daughter. She was a pillar of rifle and pistols, shot advancing Chinese from the German compound. strength for her mother and brothers. She was extremely well read She was a noted artist, photographer and architect. While First and would offer sound advice to her husband. Once when asked the Lady, she was approached by Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the role of the First Lady, she replied “ to sit next to your husband, keep Girl Scouts of America, to become active in Girl Scout leadership. -

July 2018 July 8Th, 2018 12 Men and 8 Women NBC's Meet the Press

July 2018 July 8th, 2018 12 men and 8 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 5 men and 1 woman Sen. Roy Blunt (M) Sen. Dick Durbin (M) Frm. Mayor Rudy Giuliani (M) Eugene Robinson (M) Susan Page (W) Danielle Pletka (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Margaret Brennan: 4 men and 2 women Amb. Kay Bailey Hutchinson (W) Sen. Joni Ernst (W) Sen. Christopher Coons (M) Mark Landler (M) Reihan Salam (M) Toluse Olorunnipa (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 5 men and 2 women Frm. Mayor Rudy Giuliani (M) Alan Dershowitz (M) Asha Rangappa (W) Leonard Leo (M) Sen. Richard Blumenthal (M) Sara Fagen (W) Patrick Gaspard (M) CNN's State of the Union with Jake Tapper: *With Guest Host Dana Bash 2 men and 1 woman Dr. Carole Lieberman (W) Dr. Jean Christophe Romagnoli (M) Frm. Mayor Rudy Giuliani (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: *With Guest Host Dana Perino 1 man and 2 women Amb. Kay Bailey Hutchinson (W) Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Ilyse Hogue (W) July 15th, 2018 22 men and 6 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 5 men and 1 woman Amb. Jon Huntsman (M) Sen. Mark Warner (M) Joshua Johnson (M) Amy Walter (W) Hugh Hewitt (M) Sen. Dan Sullivan (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Margaret Brennan: 7 men and 2 women Rep. Trey Gowdy (M) Sen. John Cornyn (M) Frm. Amb. Victoria Nuland (W) Tom Donilon (M) Rep. Joseph Crowley (M) Rachael Bade (W) Ben Domenech (M) Gerald Seib (M) David Nakamura (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: *With Guest Host Jonathan Karl 3 men and 2 women Amb. -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY WINTER 2019 NO. 1 THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. Both our social and economic sys- tems are based on private enterprise, from which springs initiative and ingenuity. Ours is a system where the Federal Government should undertake no govern- mental, social, or economic action, except where local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves. The overall mission of this Institution is, from its records, to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication to recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life. -

Journalism Research 2/2021 72 Editorial

Journalism Research Edited by Gabriele Hooffacker, Horst Pöttker, Tanjev Schultz and Martina Thiele 2021 | Vol. 4 (2) www.journalistik.online 72 Editorial Debate Research papers 144 Oliver Günther and Tanjev Schultz Inspire, enlighten, disagree 74 Marco Braghieri, Tobias Blanke Ten ways to ensure strong journalism and Jonathan Gray in a digital media world Journalism aggregators: an analysis of Longform.org Reviews How journalism aggregators act as site of datafication and curatorial work 151 Michael Haller: Die Reportage: Theorie und Praxis des Erzähljournalismus. 98 Marc-Christian Ollrog, Megan Hanisch [Reportage: Theory and practice of and Amelie Rook storytelling journalism] When newspeople get constructive Reviewed by Steven Thomsen An editorial study on implementing Constructive Reporting at 154 Claudia Mast et al.: »Den Mächtigen Verlagsgruppe Rhein Main auf die Finger schauen«. Zur Zukunft gedruckter Tageszeitungen in der 118 Hans Peter Bull Region [»Keeping a close eye on the How true is media reporting? powerful.«] Of bad practices and ignorance Reviewed by Silke Fürst in public communication 159 Mandy Tröger: Pressefrühling und Essay Profit. Wie westdeutsche Verlage 1989/1990 den Osten eroberten [Press 135 Valérie Robert spring and profit] France’s very own Murdoch Reviewed by Hans-Dieter Kübler Money, media, and campaigning 163 Florian Wintterlin: Quelle: Internet. Journalistisches Vertrauen bei der Recherche in sozialen Medien [Source: Internet] Reviewed by Guido Keel HERBERT VON HALEM VERLAG H H Legal Notice Journalism Research (Journalistik. Zeitschrift für Journalismusforschung) 2021, Vol. 4 (2) http://www.journalistik.online Editors Publisher Prof. Dr. Gabriele Hooffacker Herbert von Halem Verlagsgesellschaft Prof. Dr. Horst Pöttker mbH & Co. KG Prof. Dr. Tanjev Schultz Schanzenstr.