Emergent Scenography: the Collaborative Process of Conduct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenography Studies – on the Margin of Art History and Theater Studies

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2014, vol. XVI ISSN 1641-9278 Dominika Łarionow Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected] SCENOGRAPHY STUDIES – ON THE MARGIN OF ART HISTORY AND THEATER STUDIES Abstract: Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. The history of scenography to date has recorded two moments when it rose to prominence, becoming the “queen” of the spectacle: the Renaissance and modern times. The article will briefly discuss its history, to show the main reasons for the exclusion of scenography from the domain of academic research. The author will survey some recent publications on set design written by practitioners and academics. Keywords: set design – scenography – history of theater – theater. Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. Its roots reach back to the theater of ancient Greece. Even during that period, it was already a marginalized discipline. Aristotle noted in his Poetics, which can be partly regarded as representative for the ideas of his time, that although a spectacle is the work of the skenograph, its significance depends on the craftsmanship of the playwright. Therefore, he acknowledges the quality that scenography contributes to the spectacle, but in order to achieve catharsis, that ancient category associated with the reception of a work of art, a work of great literary value is needed. -

TPA4066C Advanced Scenography Syllabus Fall 20

TPA 4066C 1 Advanced Scenography – Fall 2020 3 Credits – TR 12:00-1:20 – Remote Via Zoom at Scheduled Time Instructor: Vandy Wood Office: PAC T235 Phone: 407-252-1520 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: TBD (and by confirmed appointment). University-Wide Face Covering Policy for Common Spaces and Face-to-Face Classes To protect members of our community, everyone is required to wear a facial covering inside all common spaces including classrooms (https://policies.ucf.edu/documents/PolicyEmergencyCOVIDReturnPolicy.pdf. Students who choose not to wear facial coverings will be asked to leave the classroom by the instructor. If they refuse to leave the classroom or put on a facial covering, they may be considered disruptive (please see the Golden Rule for student behavior expectations). Faculty have the right to cancel class if the safety and well-being of class members are in jeopardy. Students will be responsible for the material that would have been covered in class as provided by the instructor. Notifications in Case of Changes to Course Modality Depending on the course of the pandemic during the semester, the university may make changes to the way classes are offered. If that happens, please look for announcements or messages in Webcourses@UCF or Knights email about changes specific to this course. COVID-19 and Illness Notification Students who believe they may have a COVID-19 diagnosis should contact UCF Student Health Services (407-823-2509) so proper contact tracing procedures can take place. Students should not come to campus if they are ill, are experiencing any symptoms of COVID-19, have tested positive for COVID, or if anyone living in their residence has tested positive or is sick with COVID-19 symptoms. -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

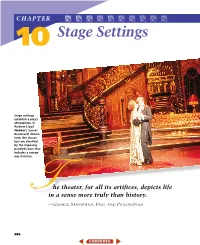

Chapter 10: Stage Settings

396-445 CH10-861627 12/4/03 11:11 PM Page 396 CHAPTER ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ 10 Stage Settings Stage settings establish a play’s atmosphere. In Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Sunset Boulevard, shown here, the charac- ters are dwarfed by the imposing paneled room that includes a sweep- ing staircase. he theater, for all its artifices, depicts life Tin a sense more truly than history. —GEORGE SANTAYANA, POET AND PHILOSOPHER 396 396-445 CH10-861627 12/4/03 11:12 PM Page 397 SETTING THE SCENE Focus Questions What are the purposes of scenery in a play? What are the effects of scenery in a play? How has scenic design developed from the Renaissance through modern times? What are some types of sets? What are some of the basic principles and considerations of set design? How do you construct and erect a set? How do you paint and build scenery? How do you shift and set scenery? What are some tips for backstage safety? Vocabulary box set curtain set value unit set unity tints permanent set emphasis shades screens proportion intensity profile set balance saturation prisms or periaktoi hue A thorough study of the theater must include developing appreciation of stage settings and knowledge of how they are designed and constructed. Through the years, audiences have come to expect scenery that not only presents a specific locale effectively but also adds an essential dimension to the production in terms of detail, mood, and atmosphere. Scenery and lighting definitely have become an integral part of contemporary play writ- ing and production. -

Scenography of Mk-Woyzeck

SCENOGRAPHY OF MK-WOYZECK by Conor Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Theatre) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2010 © Conor Moore, 2010 ABSTRACT This paper describes and discusses the lighting, video, and scenery design of MK Woyzeck, presented at the Frederic Wood Theatre from October 1st to 1 0th 2009. The design will be presented primarily through a series of photographs taken by various photographers at several points during the design, cueing, and performance phases of the production. Emphasis will be placed on the use of digital projectors to provide full illumination of the actors, referred to as Digital Video Illumination (DVI), as well as the role of the projection!set!lighting designer as an active deviser within the rehearsal process. Chapter 1 will provide a brief overview of the production concept for the piece and it’s impact on design strategies. Chapter 2 illustrates the overall execution of the design through a collection of photographs with accompanying captions describing the intention behind each of the cues depicted. In a similar fashion, Chapter 3 describes some of the advantages and challenges inherent within the DVI system and the particular projection instruments employed in this production. Chapter 4 is devoted to the actual mechanics of DVI cue construction. These are illustrated through the description of five sample cues representative of the major ways in which DVI was applied to this production. Chapter 5 summarizes the outcomes of this experimental design process through a brief conclusion. -

Stage Manager & Assistant Stage Manager Handbook

SM & ASM HANDBOOK Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre STAGE MANAGER & ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER HANDBOOK December 12, 2008 Proposed changes and updates to the Producer Handbook can be submitted in writing or by email to the General Manager. The General Manager and Active Production Chair will enter all approved changes. VTG SM HANDBOOK: December 12, 2008 1 SM & ASM HANDBOOK Stage Manager & Assistant SM Handbook CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. AUDITIONS a) Pre-Audition b) Auditions and Callbacks c) Post Auditions / Pre First Rehearsal 3. REHEARSALS a) Read Through / First Rehearsal b) Subsequent Rehearsals c) Moving to the Mainstage 4. TECH WEEK AND WEEKEND 5. PERFORMANCES a) The Run b) Closing and Strike 6. SM TOOLS & TEMPLATES 1. Scene Breakdown Chart 2. Rehearsal Schedule 3. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Guidelines for Stage Management 4. The Prompt Book VTG SM HB: December 12, 2008 2 SM & ASM HANDBOOK 5. Production Technical Requirements 6. Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 7. Rehearsal Attendance Sheet 8. Stage Management Kit 9. Sample Blocking Notes 10. Rehearsal Report 11. Sample SM Production bulletins 12. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals on Mainstage – SM Guidelines 13. Rehearsals on the Mainstage – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 14. Sample Preset & Scene Change Schedule 15. Performance Attendance Sheet 16. Stage Crew Guidelines and Information Sheet 17. Sample Prompt Book Cues 18. Use of Theatre during Performances – SM Guidelines 19. Sample Production Information Sheet for FOH & Bar 20. Sample SM Preshow Checklist 21. Sample SM Intermission Checklist 22. SM Post Show Checklist 23. -

An Excursion to and from Situational Urban Scenography

Tactics of the Other Everyday: An Excursion to and from Situational Urban Scenography Mengzhe Tang Abstract: For a scenographic reading of urban settings, attentions are directed to the small, mundane and the everyday, which penetrate the non-institutional, always neglected, but most underlying aspects of urban life. Scattered in the most ordinary corners around the city, the scenes framed by a scenographic scope could nevertheless touch upon spatial, imaginary and situational potentials in perceiving and understanding urban spatial phenomena, diverting from the real and rational into the scenographic “other world”. These small, everyday yet partly surreal scenes, coupled with the notions of Tactic (Michel de Certeau, 1984) and Construction of Situation (Guy Debord, 1957), further come to a political gesture of resisting (destroying) the overwhelming institutionalization and standardization of contemporary life, as well as urban spaces. This progress from framing, association to tactics delineates a theatrical excursion departing from the real city into the fictitious, and eventually returning back to reality, yet with some residue imaginary subversive passion in turn to transform the real urban space. Introduction: In the poetic film The Color of Pomegranates (Tsvet granata, Armenfilm 1969), the film director of Armenian descent Sergei Parajanov, with his melancholically archaic and theatrical cinematic language, created a fascinating and dream-like world, in which the life of the Armenian poet Sayat Nova and his particular epoch gradually -

LIGHTING CONTROL HISTORY Their Immediate Technological Predecessors

not exist if preset boards had not been LIGHTING CONTROL HISTORY their immediate technological predecessors. AND The first type of control for electrical MODERN PROGRAMMING lighting was simply a bank of switches STRATAGIES that turned the lights on and off. Not surprisingly, artists in the theatre were not entirely satisfied with the “lights up, lights Modern lighting control methods are down,” nature of switches in controlling governed by complex computer systems lighting for sensitive scenes. Not long that make it possible to operate hundreds after the use of electric lighting became of lights at one time. They also make it widespread, resistance dimmers were possible to use the many digital lights and developed so that it was possible to fade in accessories developed over the past two and out of scenes. Fading indicates that decades. Although each manufacturer has the lighting change occurs over a period of its own particular method of handling time, which is an important element in technical issues, the core technology that lighting design. The term blackout is used makes all of them work is basically the to describe what happens when all of the same. This chapter is not intended to be stage lights go out instantly. (or as fast as an exhaustive review of every OEM system the cooling filaments will allow) on the market, but rather as an overview Although blackouts are frequently used to of the basic philosophy that is used in indicate a sudden end to the action on designing digital products for the control stage, they are not appropriate for most of stage lighting. -

Scenography, Landscape and Memory in Estonian Open-Air Performances

TRAMES, 2008, 12(62/57), 3, 319–330 ENCOUNTERS IN LANDSCAPES: SCENOGRAPHY, LANDSCAPE AND MEMORY IN ESTONIAN OPEN-AIR PERFORMANCES Liina Unt University of Arts and Design Helsinki Abstract. Landscape and human memory are in a reciprocal relationship – landscape sustains a certain kind of remembering while memories keep it from changing too much. Living in and looking at a landscape can be regarded as acts of remembrance, where the landscape is not scenery, but a stage of action. Theatrical performances given in landscape present a special case, since they use the existing landscape for a fictional one. Regardless of the scope of scenographic intervention, landscape is experienced as an immediately present multisensory totality that the audience and actors share. This transdisciplinary study shows that theatre employs landscape memory on multiple levels (actual site of events, connotations of the landscape, the relationship between fictional history and visible markers). Scenography has the capability to reflect, express and change the relationship between landscape and memory. Productions staged in Estonian landscapes in 2000-2006 exemplify the extent that theatrical representation rests on (and benefits from) landscape memory. DOI: 10.3176/tr.2008.3.07 Keywords: environmental aesthetics, landscape, memory, performance research, scenography 1. Introduction In open-air theatre, the site of performance can be regarded as instrumental to the performance. Theatre is a synthesizing form of art, where different art forms complement one another and contribute to the process of meaning-making. Performing in ‘found space’1, which is the case in open-air theatre, makes the 1 ‘Found space’ marks the practice of performing in sites that are not built for theatre. -

Implementation of Scenography Elements in the Production

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 3, March, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Implementation of Scenography Elements in the Production of’ Creative Arts among Upper Secondary Students through Theatrical Production in the Malaysia Arts School of Johor Zolkipli Abdullah, Muhammad Fazli Taib Saerani, Syarul Azlina Sikandar To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5796 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5796 Received: 30 Jan 2019, Revised: 10 Feb 2019, Accepted: 02 March 2019 Published Online: 30 March 2019 In-Text Citation: (Abdullah, Saerani, & Sikandar, 2019) To Cite this Article: Abdullah, Z., Saerani, M. F. T., & Sikandar, S. A. (2019). Implementation of Scenography Elements in the Production of’ Creative Arts among Upper Secondary Students through Theatrical Production in the Malaysia Arts School of Johor. International Journal Academic Research Business and Social Sciences, 9(3), 1291–1297. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 3, 2019, Pg. 1291 - 1297 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 1291 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Name Affiliation Title Panel Day Time Maria Sehopoulou National And

Name Affiliation Title Panel Day Time Maria Sehopoulou National and Kapodistrian Transnational Diversities and National Singularities: the Case of Nordic Drama Abroad 14 11:00- University of Athens August Strindberg and his Reception in Greece 12:30 Svein Henrik Nyhus Centre for Ibsen Studies, Ibsen in America - a centralized narrative? Nordic Drama Abroad 14 11:00- University of Oslo 12:30 Kamaluddin Nilu University of Oslo No Local is Anymore Local: A Transcultural Adaptation of Ibsen’s Nordic Drama Abroad 14 11:00- Peer Gynt 12:30 José Camões Centre for Theatre Studies ReCET the past: Tools for a modern theatre archaeology Digital Archives 14 11:00- 12:30 John Andreasen Dramaturgy, Aarhus University, Eternal Presence – How to create a Community Play Archive? Digital Archives 14 11:00- Denmark 12:30 Bernadette Cochrane University of Queensland Remaindering the Remains: the digital, the live, and the archive Digital Archives 14 11:00- 12:30 Kotla Hanumantha rao Potti Sriramulu Telugu University Surabhi – The Pioneer in Stagecraft Echoes of Indian Pasts in the Theatre 14 11:00- 12:30 Ramakrishnan Muthiah Central University of Jharkhand Resisting the Stratified World: Understanding the Role of Folk Echoes of Indian Pasts in the Theatre 14 11:00- Theatre for the Marginalized Communities in India 12:30 Tithi Chakraborty Budge Budge Institute of Echoes of Social, Political and Economic Crises in the Theatre of Echoes of Indian Pasts in the Theatre 14 11:00- Technology Bengal, India 12:30 Sofie Taubert Institute of Media Culture and Shipwreck -

Scenography 1:1 – Direct Experience and Use of Space, As Design Tools

Scenography 1:1 – Direct Experience and Use of Space as Design Tools in Educational Activities Performance Design Pedagogies International Conference, Barbican – London 15 March 2018 Andreas Skourtis Architect, Scenographer Lecturer in Scenography, The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama Founder and Artistic Director, Performing Architectures Good morning, I am Andreas Skourtis, a practicing architect and scenographer, and lecturer in scenography at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama –University of London. In 2015 I founded, and I am artistic director of, Performing Architectures, a London based company that works internationally, and creates architectural, theatrical and scenographic spaces, merging practice and research through creative interdisciplinary laboratories. In my creative practice, and teaching practice, in the process of developing and creating three-dimensional scenographic places, I focus a lot on how to use different architectures as scenography tools. I always try to use as much as possible, and whenever I can, a space (a rehearsal room – or a studio theatre- a field) as a live 'drawing board'; and the bodies of the director, the scenographer and the actors, and sometimes some animated materials, as 'pencils'. I learn by listening the space, and I always try to inform my teaching with that learning. During research and development for a public production of A Midsummer Night's Dream I designed last year at Central, I read an article by Peter Brook, from which the following quote is: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 2017, photos from rehearsals ©Andreas Skourtis ‘…in the visual arts, ‘concept’ now replaces all the qualities of hard-earned skills of execution and development.