This Is a New File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scone Airport Master Plan Final Report

SCONE AIRPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT Prepared for Upper Hunter Shire Council June 2016 Scone Airport Master Plan Report Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 2 2 Airport Background and Regional Context ............................................................................ 4 2.1 Airport Business Model ......................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Regional Context ................................................................................................................... 6 3 Existing Airport Facilities ....................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Runway 11/29 & Runway Strip - Physical Features ............................................................... 8 3.2 Taxiways .............................................................................................................................. 10 3.3 Apron and Aircraft Parking Areas ........................................................................................ 12 3.4 Terminal Building ................................................................................................................ 12 3.5 Privately Owned Facilities .................................................................................................. -

Hunter Investment Prospectus 2016 the Hunter Region, Nsw Invest in Australia’S Largest Regional Economy

HUNTER INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS 2016 THE HUNTER REGION, NSW INVEST IN AUSTRALIA’S LARGEST REGIONAL ECONOMY Australia’s largest Regional economy - $38.5 billion Connected internationally - airport, seaport, national motorways,rail Skilled and flexible workforce Enviable lifestyle Contact: RDA Hunter Suite 3, 24 Beaumont Street, Hamilton NSW 2303 Phone: +61 2 4940 8355 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rdahunter.org.au AN INITIATIVE OF FEDERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENT WELCOMES CONTENTS Federal and State Government Welcomes 4 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Australia’s future depends on the strength of our regions and their ability to Introducing the Hunter progress as centres of productivity and innovation, and as vibrant places to live. 7 History and strengths The Hunter Region has great natural endowments, and a community that has shown great skill and adaptability in overcoming challenges, and in reinventing and Economic Strength and Diversification diversifying its economy. RDA Hunter has made a great contribution to these efforts, and 12 the 2016 Hunter Investment Prospectus continues this fine work. The workforce, major industries and services The prospectus sets out a clear blueprint of the Hunter’s future direction as a place to invest, do business, and to live. Infrastructure and Development 42 Major projects, transport, port, airports, utilities, industrial areas and commercial develpoment I commend RDA Hunter for a further excellent contribution to the progress of its region. Education & Training 70 The Hon Warren Truss MP Covering the extensive services available in the Hunter Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development Innovation and Creativity 74 How the Hunter is growing it’s reputation as a centre of innovation and creativity Living in the Hunter 79 STATE GOVERNMENT Community and lifestyle in the Hunter The Hunter is the biggest contributor to the NSW economy outside of Sydney and a jewel in NSW’s rich Business Organisations regional crown. -

Upper Hunter Economic Diversification Project

Upper Hunter Economic Diversification Project Report 3 of 3: Strategy Report Buchan Consulting June 2011 This project is supported by: Trade & Investment Office of Environment & Heritage Department of Premier & Cabinet Final Report Table of Contents Table of Contents.................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 A. Regional Economy........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 B. Major Issues.................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. A Diversification Strategy.............................................................................................................................................................. 8 D. Opportunities .............................................................................................................................................................................. 10 E. Implementation .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Upper Hunter Country Destinations Management Plan - October 2013

Destination Management Plan October 2013 Upper Hunter Country Destinations Management Plan - October 2013 Cover photograph: Hay on the Golden Highway This page - top: James Estate lookout; bottom: Kangaroo at Two Rivers Wines 2 Contents Executive Summary . .2 Destination Analysis . .3 Key Products and Experiences . .3 Key Markets . .3 Destination Direction . .4 Destination Requirements . .4 1. Destination Analysis . .4 1.1. Key Destination Footprint . .5 1.2. Key Stakeholders . .5 1.3. Key Data and Documents . .5 1.4. Key Products and Experiences . .7 Nature Tourism and Outdoor Recreation . .7 Horse Country . .8 Festivals and Events . .9 Wine and Food . .10 Drives, Walks, and Trails . .11 Arts, Culture and Heritage . .12 Inland Adventure Trail . .13 1.5. Key Markets . .13 1.5.1. Visitors . .14 1.5.2. Accommodation Market . .14 1.5.3. Market Growth Potential . .15 1.6. Visitor Strengths . .16 Location . .16 Environment . .16 Rural Experience . .16 Equine Industry . .17 Energy Industry . .17 1.7. Key Infrastructure . .18 1.8. Key Imagery . .19 1.9. Key Communications . .19 1.9.1. Communication Potential . .21 2. Destination Direction . .22 2.1. Focus . .22 2.2. Vision . .22 2.3. Mission . .22 2.4. Goals . .22 2.5. Action Plan . .24 3. Destination Requirements . .28 3.1. Ten Points of Collaboration . .28 1 Upper Hunter Country Destinations Management Plan - October 2013 Executive Summary The Upper Hunter is a sub-region of the Hunter Develop a sustainable and diverse Visitor region of NSW and is located half way between Economy with investment and employment Newcastle and Tamworth. opportunities specifi c to the area’s Visitor Economy Strengths. -

Prospects and Challenges for the Hunter Region a Strategic Economic Study

Prospects and challenges for the Hunter region A strategic economic study Regional Development Australia Hunter March 2013 Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation. © 2013 Deloitte Access Economics Pty Ltd Prospects and challenges for the Hunter region Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: The current and future shape of the Hunter economy .................................................... 3 2 The Hunter economy in 2012 .......................................................................................... 4 2.2 Population and demographics ........................................................................................... 5 2.3 Workforce and employment ............................................................................................. 8 2.4 Industrial composition .................................................................................................... 11 3 Longer term factors and implications ............................................................................ 13 3.1 New patterns in the global economy ............................................................................... 13 3.2 Demographic change ...................................................................................................... 19 -

Aviation Short Investigations 49 Issue

InsertAviation document Short Investigations title Bulletin LocationIssue 49 | Date ATSB Transport Safety Report Investigation [InsertAviation Mode] Short OccurrenceInvestigations Investigation XX-YYYY-####AB-2016-068 Final – 27 July 2016 Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. -

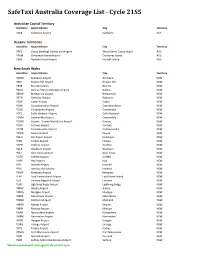

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Regional Airport Infrastructure Funding Action Plan

REGIONAL AIRPORT INFRASTRUCTURE FUNDING ACTION PLAN 1 AUSTRALIA’S REGIONAL AIRPORTS The network of over 400 regional Research conducted by ACIL Allen estimates that the total expenditure by the operators of all regional airports with airports and aerodromes across Australia fewer than 500,000 passenger movements per annum was constitutes an integral part of our economic approximately $185.4 million in 2014-15, resulting in an additional $33.4 million in spending in the rest of the infrastructure. It is critical to connecting Australian economy. These airports also employ approximately communities and enhancing broader 1,720 full time staff (2014/15), creating an additional 2,750 full economic performance. time roles in the rest of the economy. As well as providing significant employment opportunities Regional airports play a vital role in sustaining regional in local and regional economies, regional airports also economies and communities both through their direct generate catalytic economic impacts by facilitating increased expenditures, as well as through the flow-on effects of these competition because of readier access to alternative suppliers, expenditures. These airports enable access to specialist enhancing innovation through access to a wider range of skills health, education, commercial and recreational facilities and and human resources, enabling a more flexible labour market facilitate social connections. and facilitating more efficient interaction between different levels of government. They also have the ability to save lives by facilitating medical evacuations, collection and delivery of organ donations and Despite their significant contribution, Australia’s regional search and rescue, as well as supporting firefighting in areas airports face significant challenges in maintaining the services where road transport is impossible or too slow. -

Special Climate Statement 72—Dangerous Bushfire Weather in Spring 2019

Special Climate Statement 72—dangerous bushfire weather in spring 2019 18 December 2019 Special Climate Statement 72—dangerous bushfire weather in spring 2019 Version number/type Date of issue Comments 1.0 18 December 2019 Unless otherwise noted, all images in this document except the cover photo are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Australia Licence. © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 Published by the Bureau of Meteorology Cover image: Satellite image from Himawari-8 on 4 December 2019 showing plumes of smoke extending eastwards from fires burning in eastern Australia and a large area of smoke over the Tasman Sea. Some of these fires had been burning for several months after starting on days of elevated fire weather conditions in early September. 2 Special Climate Statement 72—dangerous bushfire weather in spring 2019 Table of contents Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Preceding climate conditions and drivers .......................................................................................................... 5 2. Fire weather in spring 2019 ............................................................................................................................... 7 3. Some impacts of the conditions ...................................................................................................................... 17 4. Previous notable events in New South Wales ............................................................................................... -

Hunter Investment Prospectus

2021 HUNTER INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS YOUR SMART BUSINESS, INVESTMENT & LIFESTYLE CHOICE THE HUNTER REGION THE HUNTER REGION AUSTRALIA’S LARGEST AUSTRALIA’S LARGEST REGIONAL ECONOMY REGIONAL ECONOMY The Hunter Region in NSW is Australia’s largest regional economy, with an economic output of around $57 billion pa and a population of over 747,000. Australia’s largest The Port of Newcastle regional economy with is one of Australia's It includes Greater Newcastle - the seventh over $57 billion annual largest ports with 171 million tonnes largest urban area in Australia. output and over 54,000 businesses of cargo in 2019. It is a vibrant and diverse centre with a focus Over 1.2 million on technology, research, knowledge Close proximity to annual passenger major Australian sharing, industry and innovation. It has a movements through markets dynamic start-up sector and many global Newcastle Airport companies across industries including (pre-COVID) aerospace, advanced manufacturing, mining and defence. Global top 200 Population of university 747,381 The region is situated on Australia’s main (ABS JUNE 2019 ERP) east coast transport corridor. It has sophisticated infrastructure, international gateways including an airport and deep sea Much lower property Greater Newcastle is port, its own media outlets and university costs than capital cities Australia’s 7th largest and a talent pool that is increasingly STEM city skilled and job ready. The Hunter combines an innovative economic and business environment with a Highly skilled Enviable lifestyle high standard of living, proximity to workforce Australia's largest city, Sydney and easy connections to Australia’s other capital cities. -

Air Force Association NSW News and Views World's Oldest Fighter Pilot Hangs up His Flying Boots

SITREP Air Force Association NSW News and Views World’s Oldest Fighter Pilot Hangs Up His Flying Boots by Max Blenkin August 31, 2018 This (edited) feature article first appeared in the August 2018 issue of Australian Aviation. quadron Leader Phil Frawley retired S from the RAAF at the end of June, concluding a long flying career in which he’s piloted everything from Mirages, Hornets and C-130s to Fokker DR1, P-40 Kittyhawk and Grumman Avenger warbirds. Six months more and he could have made a full half century in the RAAF, and maybe trained 500 RAAF pilots; he’s had to settle with 499. Right up to the last day, he was fully qualified to fly fast jets and at age 66 that made him the oldest serving fighter pilot in Australia and likely the world. As at 1st August last year the Guinness Book of World Records acknowledged SQNLDR Frawley, then 65, of Newcastle, NSW, Australia, as the world’s oldest active fighter pilot. A year older, 'Frawls' said he planned to try to update that record. Reflecting on fast jets and young pilots, he said of all the fighters he’s flown, the standout was the MiG-21, the Soviet-designed supersonic fighter and interceptor which first flew in 1956 and which remains in service in mostly third world air forces around the world. “When I was flying Mirages we were told the MiGs were hunks of junk and not really worthy of being an adversary; however once I learned to fly it, I soon found that it was actually in many ways superior to the Mirage.” Because so many were made and subsequently sold off as former Soviet clients updated their air forces, a significant number of MiG-21s have found their way into private hands, including one at Fighter World, Williamtown, which Frawls used to fly. -

Scone & Upper Hunter Airport

SCONE & UPPER HUNTER AIRPORT STRATEGIC PLAN 2014 ‐ 2019 VISION The Scone & Upper Hunter Airport Strategic Plan focuses on good stewardship of this community asset by establishing objectives, developing strategies, and formulating action plans consistent with realising the vision for Scone & Upper Hunter Airport and the vision of the Upper Hunter Shire Council (UHSC). UHSC VISION A Quality Rural Lifestyle in a Vibrant, Caring and Sustainable Community UHSC MISSION To enhance the quality of life of all Shire residents by the provision of appropriate services and facilities through effective and efficient management of resources. To serve the community through equality of opportunity and involvement. To build a prosperous environmentally sustainable future. To foster sustainable, economic and social growth. The Scone & Upper Hunter Airport Strategic Plan proposes an airport that will satisfy the potential demand for aviation services in a way which is compatible with the environment, the local community and the rational development of facilities, yet maintain flexibility to cater for future changes in demand. AIRPORT VISION A well‐planned and serviced Airport facility managed in a manner that attracts environmentally responsible economic development opportunities to the Upper Hunter region. AIRPORT MISSION To productively use the airport’s assets for the economic and social benefit of the residents of the Upper Hunter local government area. To manage and develop the airport in a sustainable manner. 2 Scone & Upper Hunter Airport – Strategic Plan 2014‐2019 TRIM‐INT‐4327/14 BACKGROUND The airstrip itself is a fully sealed runway 1404 metres in length with a 100 metre Runway End Scone & Upper Hunter Airport was constructed in Safety Area (RESA), night landing, fuel and 1958 by the former Scone Shire Council.