Life History of the Broad-Billed Motmot, with Notes on the Rufous Motmot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

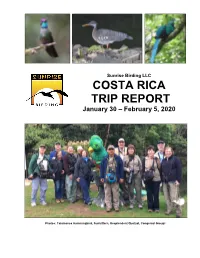

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Auto Guia Version Ingles

Parque Natural Metropolitano Tel: (507) 232-5516/5552 Fax: (507) 232-5615 www.parquemetropolitano.org Ave. Juan Pablo II final P.O. Box 0843-03129 Balboa, Ancón, Panamá República de Panamá 2 Taylor, L. 2006. Raintree Nutrition, Tropical Plant Database. http://www.rain- Welcome to the Metropolitan Natural Park, the lungs of Panama tree.com/plist.htm. Date accessed; February 2007 City! The park was established in 1985 and contains 232 hectares. It is one of the few protected areas located within the city border. Thomson, L., & Evans, B. 2006. Terminalia catappa (tropical almond), Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources You are about to enter an ecosystem that is nearly extinct in Latin (PAR), Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). http://www.traditionaltreeorg . Date accessed March America: the Pacific dry forests. Whether your goals for this walk 2007-04-23 are a simple walk to keep you in shape or a careful look at the forest and its inhabitants, this guide will give you information about Young, A., Myers, P., Byrne, A. 1999, 2001, 2004. Bradypus variegatus, what can be commonly seen. We want to draw your attention Megalonychidae, Atta sexdens, Animal Diversity Web. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Bradypus_var toward little things that may at first glance seem hidden away. Our iegatus.html. Date accessed March 2007 hope is that it will raise your curiosity and that you’ll want to learn more about the mysteries that lie within the tropical forest. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The contents of this book include tree identifications, introductions Text and design: Elisabeth Naud and Rudi Markgraf, McGill University, to basic ecological concepts and special facts about animals you Montreal, Canada. -

Observations on the Nest, Eggs, and Natural History of the Highland Motmot (Momotus Aequatorialis) in Eastern Ecuador

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 17: 151–154, 2006 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS ON THE NEST, EGGS, AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE HIGHLAND MOTMOT (MOMOTUS AEQUATORIALIS) IN EASTERN ECUADOR Harold F. Greeney 1,2, Lana H. Jamieson1, Robert C. Dobbs1, Paul R. Martin1,2, & Rudolphe A. Gelis1 1Yanayacu Biological Station and Center for Creative Studies, c/o Foch 721 y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. E-mail: [email protected] 2Research Associate, Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales, Rumipamba 341 y Av. Shyris, Quito, Ecuador. Observaciones sobre el nido, huevos, y historia natural del Momoto Montañero (Momotus aequato- rialis) en el este del Ecuador. Key words: Nest, eggs, natural history, predators, diet, army ants, Andes, cloud forest, Highland Motmot, Momotus aequatorialis. The Highland Motmot (Momotus aequatorialis) privately owned reserve of Cabañas San is the most montane of its congeners (3 spp.), Isidro, Napo Province, 5 km west of Cosanga. preferring elevations between 1000 and 2100 Observations were made opportunistically m (ranging as high as 3100 m), and generally during the course of other field work. replacing Blue-crowned Motmot (M. momota) at these elevations from Colombia to Peru Nest and eggs. While we encountered several (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Snow 2001). active nests, only one was excavated and mea- While a fair amount has been written con- sured. This nest was first observed on 9 Feb- cerning the breeding and foraging ecology of ruary 2005, when an adult bird was flushed the more wide-spread Blue-crowned Motmot, from an earthen tunnel by gently probing little is known for its congeners, and the inside with a thin stick. -

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 42 no. 19 22 november 1967 ON THE NOTODONTIDAE (LEPIDOPTERA) FROM NEW GUINEA IN THE LEIDEN MUSEUM by S. G. KIRIAKOFF Instituut voor Dierkunde, Rijksuniversiteit, Ghent, Belgium With 15 text-figures Summary. — An annotated list of the Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) from New Guinea, in the collections of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden; with descriptions of two new genera and twelve new species. Samenvatting. — Een geannoteerde lijst der Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) van Nieuw Guinea, in de verzamelingen van het Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden; met beschrijvingen van twee nieuwe geslachten en twaalf nieuwe soorten. This paper deals with the Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) from New Guinea, now in the collections of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden. Most of the specimens were collected by the late L. J. Toxopeus, who took part in the Netherlands Indian — American Expedition to Netherlands New Guinea (3rd Archbold Expedition to New Guinea 1938-'39). Other material was collected by the Netherlands Expedition to the Star Mountains ("Sterren• gebergte"), 1959 (collector not stated on the labels; "Neth. N.G. Exp." in text). Other collectors were W. Stüber (mainly in the outskirts of Mt. Bewani) and R. Straatman (Biak, Schouten Is.; Hollandia); finally, some specimens were collected at Hollandia by L. D. Brongersma and L. B. Holthuis. The results of the various expeditions form a very good sample of the Notodontid fauna of New Guinea. Most of the genera now known and many species, are represented, with the usual predominance of the three large genera Quadricalcarifera Strand, Cascera Walker, and Omichlis Hampson, the latter two almost endemic and very characteristic. -

Birding the Atlantic Rainforest, South-East Brazil Itororo Lodge and Regua 11Th – 20Th March 2018

BIRDING THE ATLANTIC RAINFOREST, SOUTH-EAST BRAZIL ITORORO LODGE AND REGUA 11TH – 20TH MARCH 2018 White-barred Piculet (©Andy Foster) Guided and report compiled by Andy Foster www.serradostucanos.com.br Sunday 11th March The following 10 day tour was a private trip for a group of 4 friends. We all flew in from the UK on a BA flight landing the night of the 10th and stayed in the Linx Hotel located close to the International airport in Rio de Janeiro. We met up for breakfast at 07.00 and by 08.00 our driver had arrived to take us for the 2.5 hour drive to Itororo Lodge where we were to spend our first 6 nights birding the higher elevations of the Serra do Mar Mountains. On the journey up we saw Magnificent Frigatebird, Cocoi Heron, Great White Egret, Black-crowned Night Heron, Neotropic Cormorant and Roadside Hawk. By 10.30 we had arrived at the lodge and were greeted by Bettina and Rainer who would be our hosts for the next week. The feeders were busy at the lodge and we were soon picking up new species including Azure-shouldered Tanager, Brassy-breasted Tanager, Black-goggled Tanager, Sayaca Tanager, Ruby- crowned Tanager, Golden-chevroned Tanager, Magpie Tanager, Burnished-buff Tanager, Plain Parakeet, Maroon-bellied Parakeet, Rufous-bellied Thrush, Green-winged Saltator, Pale-breasted Thrush, Violet- capped Woodnymph, Black Jacobin, Scale-throated Hermit, Sombre Hummingbird, Brazilian Ruby and White-throated Hummingbird…. not bad for the first 30 minutes! We spent the last hour or so before lunch getting to grips with the feeder birds, we also picked up brief but good views of a Black-Hawk Eagle as it flew through the lodge gardens. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Rufous Hummingbirds Are Very Docile Recently Handled

To Mexico and Back Again Southeast’s Smallest Migrants by Bob Armstrong and Marge Hermans from Southeast Alaska's Natural World In early summer in South- Tracking birds as small as hummingbirds east Alaska, one of the great pleasures to answer such questions is difficult. But for residents is keeping bright red sugar- some insights have come from the work of Adult male water feeders filled with nectar to feed ru- Bill Calder, a researcher and professor at the hummingbirds have fous hummingbirds. Buzzing and sparring, University of Arizona, who studied rufous brilliant red “gorgets” glinting in shades of red-brown and metallic hummingbirds for more than 30 years. (throat feathers). green, the birds often jockey noisily with Calder found that hummingbirds stop Tiny barbules on each other for the chance to sip their next to refuel in high mountain meadows just as the feathers reflect meal. They seem like tiny miracles—and in- certain alpine and subalpine flowers are at increased light at deed they are. They have traveled thousands the peak of blooming. In July and August certain angles, so the of miles from their wintering grounds in some appear in meadows of the Coast and bird’s gorget seems to Mexico to nest in Southeast Alaska. Sierra Mountains at elevations of 5,500 flash brilliant color as Hummingbirds begin arriving in early to to 7,000 feet, perhaps visiting the same it moves about. mid- April, but by late June the males will be patches of flowers they visited during past on their way south again. Females and young fall migrations. -

Momotus Bahamensis (Trinidad Motmot)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Momotus bahamensis (Trinidad Motmot) Family: Momotidae (Motmots) Order: Coraciiformes (Kingfishers, Bee-eaters, and Motmots) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig.1. Trinidad motmot, Momotus bahamensis. [http://neotropical.birds.ccornell.edu/portal/species/overview?pp_spp=7561016, downloaded 14 October 2012] TRAITS. This is one of the largest species of motmot (Skutch, 1983), with a conspicuous blue racquet tail and grey legs (Fig. 1). Formerly considered a subspecies of the blue-crowned motmot M. momotus, it is now a separate species M. bahamensis endemic to (only found in) Trinidad and Tobago. Total length males 46 cm, females also 46 cm (Schulenberg & Thomas, 2010). Short grey legs, its body tilted obliquely forward and its well developed tail extended back vertically (Styles & Skutch, 1989); males mean wing length 135 mm, females 138 mm (Schulenberg & Thomas 2010); 4-toed feet with a single toe facing the rear and the inner toe joined to the middle toe (Graham, 2012); mask-like head one-third in proportion to body and pointed bill (Schulenburg & Thomas 2010); saw-edged or serrated bill, used in crushing and cutting; well developed tactile bristles, two tail feathers that are central and much longer than the others (Graham, 2012). Colour: feathers green, head with a blue crown, a black colour around eyes in the shape of a mask with a border in various shades of green (Skutch, 1983); reddish brown UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour throat, belly and breast; broad basally dark blue racket-like tip (Schulenberg & Thomas, 2010); fledglings are similar to adult, but lack the black breast streak, have a sooty black mask and lack tail (Graham, 2012). -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

The Wag-Display of the Blue-Crowned Motmot (Momotus Momota) As a Predator-Directed Signal Elise Nishikawa University of Colorado Boulder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2011 The wag-display of the blue-crowned motmot (Momotus momota) as a predator-directed signal Elise Nishikawa University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Nishikawa, Elise, "The aw g-display of the blue-crowned motmot (Momotus momota) as a predator-directed signal" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 656. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The wag-display of the blue-crowned motmot (Momotus momota) as a predator-directed signal Elise Nishikawa Dr. Alexander Cruz (advisor) Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology March 18, 2011 Committee Members: Dr. Alexander Cruz, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Dr. Barbara Demmig-Adams, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Dr. Jaelyn Eberle, Department of Geological Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 4 LITERATURE OVERVIEW.................................................................... -

RCP Have Been Created, Except Two 'Phase In'

CORACIIFORMES TAG REGIONAL COLLECTION PLAN Third Edition, December 31, 2008 White-throated Bee-eaters D. Shapiro, copyright Wildlife Conservation Society Prepared by the Coraciiformes Taxon Advisory Group Edited by Christine Sheppard TAG website address: http://www.coraciiformestag.com/ Table of Contents Page Coraciiformes TAG steering committee 3 TAG Advisors 4 Coraciiformes TAG definition and taxonomy 7 Species in the order Coraciiformes 8 Coraciiformes TAG Mission Statement and goals 13 Space issues 14 North American and Global ISIS population data for species in the Coraciiformes 15 Criteria Used in Evaluation of Taxa 20 Program definitions 21 Decision Tree 22 Decision tree diagrammed 24 Program designation assessment details for Coraciiformes taxa 25 Coraciiformes TAG programs and program status 27 Coraciiformes TAG programs, program functions and PMC advisors 28 Program narratives 29 References 36 CORACIIFORMES TAG STEERING COMMITTEE The Coraciiformes TAG has nine members, elected for staggered three year terms (excepting the chair). Chair: Christine Sheppard Curator, Ornithology, Wildlife Conservation Society/Bronx Zoo 2300 Southern Blvd. Bronx, NY 10460 Phone: 718 220-6882 Fax 718 733 7300 email: [email protected] Vice Chair: Lee Schoen, studbookkeeper Great and Rhino Hornbills Curator of Birds Audubon Zoo PO Box 4327 New Orleans, LA 70118 Phone: 504 861 5124 Fax: 504 866 0819 email: [email protected] Secretary: (non-voting) Kevin Graham , PMP coordinator, Blue-crowned Motmot Department of Ornithology Disney's Animal Kingdom PO Box 10000 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 Phone: (407) 938-2501 Fax: 407 939 6240 email: [email protected] John Azua Curator, Ornithology, Denver Zoological Gardens 2300 Steele St. -

New Information on the Status and Distribution of the Keel-Billed Motmot Electron Carinatum in Belize, Central America

COTINGA 6 New information on the status and distribution of the Keel-billed Motmot Electron carinatum in Belize, Central America Bruce W. Miller and Carolyn M. Miller La distribución regional del Electron carinatum es resumido, con especial atención cuanto al status y distribución en Belize. Son presentadas todas las observaciones en dicho país conocidas por los autores. Importantes poblaciones de Electron carinatum están presentes en Chiquibul National Park y la cuenca de río Mullins, con poblaciones más pequeñas en Slate Creek Preserve, Tapir Mountain Nature Reserve y en la cumbre del Mt. Pine. Sus necesidades en cuanto al hábitat y vocalizaciones son discutidas; nuevas informaciones acerca de estos temas están ayudando a delucidar el verdadero status de esta rara especie. Introduction unpublished data collected since the publication The Keel-billed Motmot Electron carinatum has of Collar et al.7. always been considered the rarest of its family17. Found locally in humid lowland and montane Regional distribution forest on the Caribbean slopes (Map 1) of Mexico, The Keel-billed Motmot has long been consid Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and ered rare in Mexico4 and thought extinct due to Costa Rica1, it has been considered very rare habitat loss, with no records since 19527. His throughout its range6. The status of this species torical records are from east of the Isthmus de in Belize was obscure until the early 1990s. Here Tehuantepec; in 1995 one was reported at San we present a comprehensive review of its status Isidro la Gringa during intensive biodiversity within the country, primarily based on new and surveys in Oaxaca (A.