Rufous Hummingbirds Are Very Docile Recently Handled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 42 no. 19 22 november 1967 ON THE NOTODONTIDAE (LEPIDOPTERA) FROM NEW GUINEA IN THE LEIDEN MUSEUM by S. G. KIRIAKOFF Instituut voor Dierkunde, Rijksuniversiteit, Ghent, Belgium With 15 text-figures Summary. — An annotated list of the Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) from New Guinea, in the collections of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden; with descriptions of two new genera and twelve new species. Samenvatting. — Een geannoteerde lijst der Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) van Nieuw Guinea, in de verzamelingen van het Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden; met beschrijvingen van twee nieuwe geslachten en twaalf nieuwe soorten. This paper deals with the Notodontidae (Lepidoptera) from New Guinea, now in the collections of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden. Most of the specimens were collected by the late L. J. Toxopeus, who took part in the Netherlands Indian — American Expedition to Netherlands New Guinea (3rd Archbold Expedition to New Guinea 1938-'39). Other material was collected by the Netherlands Expedition to the Star Mountains ("Sterren• gebergte"), 1959 (collector not stated on the labels; "Neth. N.G. Exp." in text). Other collectors were W. Stüber (mainly in the outskirts of Mt. Bewani) and R. Straatman (Biak, Schouten Is.; Hollandia); finally, some specimens were collected at Hollandia by L. D. Brongersma and L. B. Holthuis. The results of the various expeditions form a very good sample of the Notodontid fauna of New Guinea. Most of the genera now known and many species, are represented, with the usual predominance of the three large genera Quadricalcarifera Strand, Cascera Walker, and Omichlis Hampson, the latter two almost endemic and very characteristic. -

Birding the Atlantic Rainforest, South-East Brazil Itororo Lodge and Regua 11Th – 20Th March 2018

BIRDING THE ATLANTIC RAINFOREST, SOUTH-EAST BRAZIL ITORORO LODGE AND REGUA 11TH – 20TH MARCH 2018 White-barred Piculet (©Andy Foster) Guided and report compiled by Andy Foster www.serradostucanos.com.br Sunday 11th March The following 10 day tour was a private trip for a group of 4 friends. We all flew in from the UK on a BA flight landing the night of the 10th and stayed in the Linx Hotel located close to the International airport in Rio de Janeiro. We met up for breakfast at 07.00 and by 08.00 our driver had arrived to take us for the 2.5 hour drive to Itororo Lodge where we were to spend our first 6 nights birding the higher elevations of the Serra do Mar Mountains. On the journey up we saw Magnificent Frigatebird, Cocoi Heron, Great White Egret, Black-crowned Night Heron, Neotropic Cormorant and Roadside Hawk. By 10.30 we had arrived at the lodge and were greeted by Bettina and Rainer who would be our hosts for the next week. The feeders were busy at the lodge and we were soon picking up new species including Azure-shouldered Tanager, Brassy-breasted Tanager, Black-goggled Tanager, Sayaca Tanager, Ruby- crowned Tanager, Golden-chevroned Tanager, Magpie Tanager, Burnished-buff Tanager, Plain Parakeet, Maroon-bellied Parakeet, Rufous-bellied Thrush, Green-winged Saltator, Pale-breasted Thrush, Violet- capped Woodnymph, Black Jacobin, Scale-throated Hermit, Sombre Hummingbird, Brazilian Ruby and White-throated Hummingbird…. not bad for the first 30 minutes! We spent the last hour or so before lunch getting to grips with the feeder birds, we also picked up brief but good views of a Black-Hawk Eagle as it flew through the lodge gardens. -

Life History of the Broad-Billed Motmot, with Notes on the Rufous Motmot

LIFE HISTORY OF THE BROAD-BILLED MOTMOT, WITH NOTES ON THE RUFOUS MOTMOT ALEXAWDERF. SKUTCH N earlier papers (1945, 1947, 1964) 1 gave accounts of the habits of three I species of motmots that inhabit more or less open country, or cool woodland on high mountains. The present paper deals with two species of the wet lowland forest. The nests of these two motmots that we chiefly studied were in sight of each other on the “La Selva” nature preserve, which lies along the left bank of the Rio Puerto Viejo just above its confluence with the Rio Sarapiqui, a tributary of the Rio San Juan in the Caribbean lowlands of northern Costa Rica. They were watched during two visits to this locality, from April to June in 1967 and from March to early June in the following year. The heavy forest of this very rainy region, with its tall, epiphyte-burdened trees, its undergrowth dominated by low palms, and its exceptionally rich avifauna, has been well described by Slud (1960). BROAD-BILLEDMOTMOT (Electron platyrhynchum) One of the smaller members of its family, the Broad-billed Motmot is about 12 inches long. The foreparts of its short body, including the head, neck, and chest, are mainly cinnamon-rufous, with a large black patch on either side, covering the cheeks and auricular region, another black patch in the center of the foreneck, and greenish blue on the chin and upper throat. The posterior parts of the body, including the back and rump, breast and abdomen, are green, more olivaceous above, more bluish below. -

ALPHA PRODUCT ITEMIZATION JANUARY 2016 REQUESTING: Cuttings Memos Chain Sets Road Samples

ALPHA PRODUCT ITEMIZATION JANUARY 2016 REQUESTING: Cuttings Memos Chain Sets Road Samples AMAZING ____1700-06 DUNE BESPOKE ____9000-01 ASTONISH ____1700-07 CINDER ____1550-01 ANDERSON ____9000-02 AWESOME ____1700-08 STORM ____1550-02 MORTIMOR ____1550-03 HERBERT ____9000-03 EMINENT ____1700-09 OTTER ____1550-04 DEGE ____9000-04 EXCEPTIONAL ____1700-10 COCOA ____1550-05 KILGOUR ____9000-05 GLORIOUS ____1550-06 STOWERS ____9000-06 INSPIRING ARTIFICE ____1550-07 BARRIE ____9000-07 MAGICAL ____9350-01 YOUNG ____1550-08 HAWKES ____9000-08 MARVELOUS ____9350-02 MOORE ____1550-09 SINCLAIR ____1550-10 GIEVES ____9000-09 MEMORABLE ____9350-03 DeBAKER ____1550-11 MORGAN ____9000-10 PROMINENT ____9350-04 EVANS ____1550-12 STEED ____9000-11 REFRESHING ____9350-05 HUDSON ____1550-13 SHEPPARD ____9000-12 SIGNIFICANT ____1550-14 DAVIES ____9000-13 SUBLIME BEETLE ____1550-15 OZWALD ____1550-16 NORTON ____9000-14 SUPERB ____4750-01 ABAX ____1550-17 HUNTSMAN ____9000-15 TERRIFIC ____4750-02 BORST ____1550-18 HITCHCOCK ____9000-16 WONDERFUL ____4750-03 MARSH ____1550-19 NUTTERS ____4750-04 ALDER ____1550-20 CHESTER ____1550-21 HUALITY ARRIVAL ____4750-05 BLAUER ____3750-01 TWILIGHT ____4750-06 RUFOUS BILTMORE COLLECTION ____3750-02 FAIRVIEW ____4750-07 CLYTE ____5500-20 CELEDON ____3750-03 HIGHLAND ____4750-08 BONTE ____5500-25 SEAFOAM ____3750-04 LAPIS ____4750-09 AGONE ____5500-30 MOSS ____3750-05 CHARMED ____4750-10 LARCH ____5500-40 BLACK ____3750-06 CONCERTO ____4750-11 BRUIN ____5500-55 SAND ____3750-07 TOWNSEND ____4750-12 RANDIGER ____5500-60 TAUPE -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

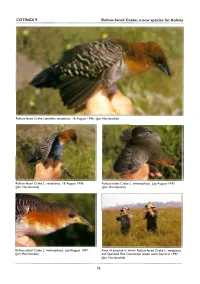

Rufous-Faced Crake Laterallus Xenopterus

COTINGA 9 Rufous-faced Crake: a new species for Bolivia Rufous-faced Crake Laterallus xenopterus. 18 August 1996. (Jon Hornbuckle) Rufous-faced Crake L. xenopterus. 18 August 1996. Rufous-sided Crake L. melanophaius. July/August 1997. (Jon Hornbuckle) (Jon Hornbuckle) Rufous-sided Crake L. melanophaius. July/August 1997. Area of savanna in which Rufous-faced Crake L. xenopterus (Jon Hornbuckle) and Speckled Rail Coturnicops notata were found in 1997. (Jon Hornbuckle) 7 6 COTINGA 9 Rufous-faced Crake Laterallus xenopterus: a new species for Bolivia, with notes on its identification, distribution, ecology and conservation Robin Brace, Jon Hornbuckle and Paul St Pierre Se describen los primeros registros de Laterallus xenopterus para Bolivia, en base a un individuo capturado el 18 agosto 1996 y tres observaciones obtenidas durante agosto 1997, todas en la Estación Biológica del Beni (EBB) (dpto. Beni). Anteriormente a nuestras observaciones, la distribución conocida de esta especie, considerada amenazada7, se extendía por sólo unos pocos sitios en Paraguay y un área del Brasil. Las aves fueron localizadas en la sabana semi-inundada caracterizada por la vegetación continua separada por angostos canales, los que claramente facilitan los desplazamientos a nivel del suelo. Si bien el registro de 1996 muestra que L. xenopterus puede vivir junto a L. melanophaius, nuestras observaciones en 1997 indican, concordando con informaciones anteriores, que L. xenopterus parece evitar áreas cubiertas por m ás que unos pocos centímetros de agua. Se resumen los detalles de identificación, enfatizando las diferencias con L. melanophaius. De particular im portancia son (i) el notable barrado blanco y negro en las cobertoras alares, terciarias y escapulares; (ii) la extensión del color rufo de la cabeza sobre la nuca y la espalda, y (iii) el pico corto y relativamente profundo, en parte de color gris-turquesa. -

The Rufous-Faced Crake (Laterallus Xenopterus) and Its Paraguayan Congeners

THE WILSON BULLETIN A QUARTERLYMAGAZINE OF ORNITHOLOGY Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society VOL. 93, No. 2 JUNE 1981 PAGES 137-300 Wilson Bull., 93(2), 1981, pp. 137-144 THE RUFOUS-FACED CRAKE (LATERALLUS XENOPTERUS) AND ITS PARAGUAYAN CONGENERS ROBERT W. STORER The Black Rail (Laterullus jamaicensis) and other crakes of the genus Luterallus are among the least known American birds, and Ripley (1977:192) points out that “of all the rail family, this group of species collectively is the least studied.” This is not surprising because they are secretive birds living in dense grassy places. But one relatively tame species, the Galapagos Rail (L. spilonotus) has been well studied in the field (Franklin et al. 1979). A second species, the Red-and-White Crake (L. leucopyrrhus) is commonly kept in aviaries where some of its habits have been reported (Meise 1934, Everitt 1962, Levi 1966). Museum spec- imens of Luterullus are few, hence their distribution and status are poorly known; anatomical material is even scarcer. The least known species of the group, the Rufous-faced Crake (L. xen- opterus), was first taken in Paraguay in 1933 and described the following year (Conover 1934). It was not found again until Philip Myers rediscov- ered it in 1976 and Rick Hansen in 1978 (Myers and Hansen 1980). The species has not been illustrated previously, probably because the tail was missing from the type specimen and information on the color of the soft parts was not available. In 1979, I spent 5 weeks in Paraguay with a field party from the Uni- versity of Michigan Museum of Zoology led by Philip Myers, III. -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

970191 • Hummingbirds

970191 • Hummingbirds BOOTED RACKET-TAIL* RUBY-THROATED BROAD-TAILED* File: WL2091 (C) File: WL2092 (C) File: WL2093 (C) 3.39"W X 3.47"H 3.51"W X 3.65"H 3.86"W X 3.09"H ST: 11,821 ST: 17,738 ST: 15,700 Colors: 12 Colors: 18 Colors: 19 1. Lt. Avocado 1. Pearl 1. Beige 2. Med. Avocado2 2. Lt. Lt. Lime 2. Dk. Umber 3. Dk. Lime 3. Dk. Lime 3. Avocado2 4. Lt. Green 4. Lt. Green2 4. Dk. Avocado2 5. Lt. Lt. Umber 5. Lt. Lt. Umber 5. Dk. Dk. Avocado 6. Blue 6. Pearl 6. Lt. Beige 13. White 7. White 7. Lt. Avocado 7. Lt. Blue2 14. Silver 8. Dk. Gray 8. Dk. Lime 8. Lt. Lt. Blue Gray 15. Lt. Lt. Lime 9. Dk. Charcoal 9. Lt. Taupe 14. Dk. Dk. Gray 9. White 16. Dk. Fuschia 10. Lt. Pink2 10. Beige 15. Dk. Charcoal 10. Blue5 17. Lt. Umber 11. Fuschia2 11. Gray 16. Red 11. Yellow2 18. Umber 12. Dk. Pink 12. Med. Taupe 17. Lt. Red3 12. Lt. Lt. Brown3 19. Dk. Charcoal 13. Dk. Brown 18. Med. Red2 BLUE-THROATED LONG-TAILED HERMIT BLACK-CHINNED* File: WL2094 (C) File: WL2095 (C) File: WL2096 (C) 3.87"W X 3.26"H 3.83"W X 3.49"H 3.82"W X 3.46"H ST: 14,432 ST: 16,792 ST: 14,672 Colors: 16 Colors: 11 Colors: 17 1. Med. Lime 1. Lime 1. Lt. Lt. Lime 2. Dk. Avocado2 2. Lt. -

Smith's Longspur: a Case of Neglect by Alan 1

2 Smith's Longspur: A Case of Neglect by Alan 1. Ryff On 29 September 1985 at longspur to lack the descriptive Chippewa Park in Thunder Bay, subsection "Plumages." Just Thunder Bay District, Mike fragments of Oberholser's (1974) Matheson and Alan Wormington description match the field notes flushed a peculiar looking taken on the bird at Thunder Bay. longspur whose tail flashed with Thus I had to seek information extra white. Wormington sub elsewhere. I studied the 62 sequently showed this bird to Nick specimens of Smith's Longspur at Escott and me. It proved to be a the University ofMichigan Smith's Longspur (Calcarius pictus). Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor We observed it for over an hour at (hereafter UMMZ). Because four distances of 1-6 m. Since the of the specimens are juveniles, I streaks on its breast were more began to see the misleading conspicuous than the streaks of the aspects of certain field guides. Smith's Longspurs illustrated in Each juvenile was collected at the National Geographic Society Churchill, Manitoba: #83995, a (hereafter NGS) guide (1983), we male, on 5 August 1936; #83996, a I believed that this bird was an male, on 5 August 1936; #166586, a !' immature. But were we correct? female, on 28 July 1938; and This became a difficult question to #217737, a female labelled 22 days answer. old, on 24 July 1966. Frank M. Chapman had less In addition to specimens and available information than his publications, I used my field notes, counterparts of today. In 1911, he which Escott, Matheson, and I concluded that figure 6 of a Wormington verified at the time of I~ Fuertes' painting originally observation. -

Uniform Color Descriptions Glossary of Terms

The International Cat Association Uniform Color Descriptions and Glossary of Terms Version D (09/04/20) Preface to By-Laws, Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules Uniform Color Descriptions and Standards The By-Laws take precedence over ALL other Rules, followed by the Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules, and Uniform Color Descriptions, in that order. The Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules, and Uniform Color Descriptions shall take precedence over any individual Breed Standard UNLESS that Standard is MORE restrictive than the general rules applying to ALL breeds, in which case the Standard shall take precedence. TICA Uniform Color Descriptions, Page 2 Version D 09/04/20 Uniform Color Descriptions Table of Contents 71 Categories, Divisions and Colors. ........................................................................ 4 72 Solid Divisions ..................................................................................................... 8 73 Tortoiseshell Divisions. ........................................................................................ 8 74 Tabby Divisions. .................................................................................................. 9 75 Silver and/or Smoke Divisions. .......................................................................... 14 76 Any Color with White Divisions. ......................................................................... 18 Color Definitions ........................................................................................................